Santiago introduction and post-screening discussion with Haden Guest and João Moreira Salles.

Transcript

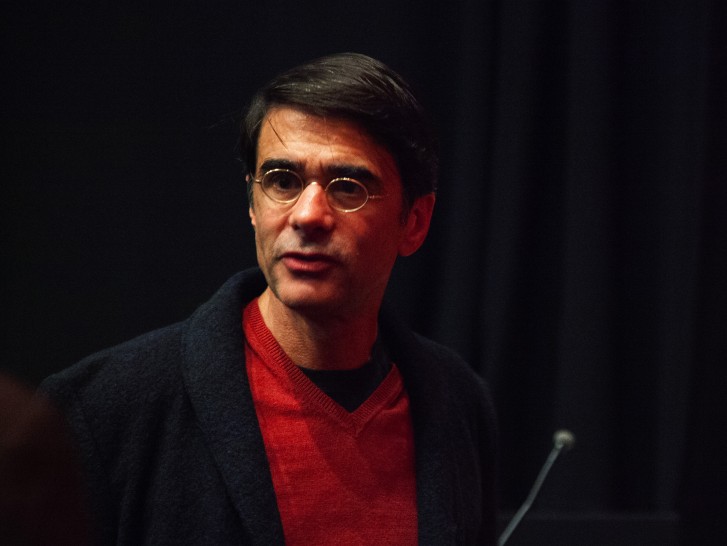

Haden Guest 0:25

Good evening ladies and gentlemen. My name is Haden Guest and I'm enormously pleased to welcome tonight Brazilian filmmaker João Moreira Salles for the first of two evenings dedicated to his documentaries. Tomorrow night we're going to see his extraordinary and much celebrated film No Intenso Agora / In the Intense Now, a meditation on revolution and memory inspired by footage he found most likely shot by his mother, documenting her voyage to China in the late 1960s. But tonight, we will present and discuss an earlier work Santiago from 2007 that in many ways, procedures and richly complements Moreira Salles’ latest film, while also breaking new ground entirely of its own. Santiago is also inspired by rediscovered footage, but in this case, hours of film shot by João Moreira Salles himself thirteen years before for a film he could never bring himself to finish, a portrait of Santiago Badariotti Merlo, who had worked as a butler for the Moreira Salles family for over thirty years and had been an especially beloved figure to the Salles children. Filmed after his retirement in his tiny apartment, the extravagant, fabulously inventive and fascinating figure of Santiago seems in so many ways the ideal subject for a young documentary filmmaker. Able to regale the camera with endless hours of richly detailed stories about exotic faraway places, recitations from the voluminous history of the aristocratic literati that he dedicated himself to, avocations of a past still glowing with full moons and enchantment and animated by evocative poetry by Santiago's captivating persona. And yet, the film could not be finished for reasons only later Moreira Salles with rare candor and honesty begins to discover by asking himself before us the viewer why his efforts to edit and to realize the film were frustrated and ultimately failed.

At the beginning of No Intensa Agora, Moreira Salles states, “We do not always know what we are filming,” a humbling and important confession that also informs tonight's deeply personal film which has the courage to question his original motives and his limitations as a filmmaker and artists with such a personal connection to his subject. Too much praise was given quite recently, to a film from Mexico, Roma, made by a man of privilege about a worker, a servant who toiled for his family. The result is a profoundly problematic romanticization of suffering and hardship that uses a [UNKNOWN] happy ending, to force false reconciliation upon a larger still unsolved problem, a class in equity and structural injustice. Santiago, whose revealing subtitle is “A Reflection on Raw Footage” refuses precisely any such exploitative tactic by deeply questioning the filmmaker's original agenda and by extension, the agenda of documentarians who claim a certainty and stability in the images they record as fact, as record, as vehicles for messages imposed upon them.

I'm so happy and really thrilled that we have a chance to watch this film together and then to have a conversation afterwards with João Moreira Salles, and I need to thank all of those who generously partnered with the Harvard Film Archive to make his visit possible. I want to start first with two dear colleagues from the Department of Romance Languages and Literatures, Bruno Carvalho and Mariano Siskind. They're both esteemed professors and scholars whose wide-ranging interests include cinema—and expertise I should say. Tomorrow night they will be joining João Moreira Salles for conversation about No Intenso Agora. I also want to give special thanks to the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies and to its Brazil Studies program. I'd like to ask you to please to turn off any cell phones, any electronic devices. Please refrain from using them, and please me join me in welcoming João Moreira Salles.

[APPLAUSE]

João Moreira Salles 4:52

Thank you very much Haden. Thank you very much Bruno. The [Harvard Film Archive]. It's a pleasure to be here. I'll be really brief. I was not expecting this introduction. And it's only downhill from now, after this introduction. I'm sorry, the film will not be as good as it seems. So thank you very much for those kind words.

And it's a strange feeling I have these days. I have a strange relationship to the film itself, which I don't think it's a bad thing. But at the end, we can talk about that. Thank you very much. I hope you enjoy the film. It's brief. So that's good. It's about seventy minutes. A little bit more, but not too long. Thank you very much. I'll see you at the end. Bye-bye.

[APPLAUSE]

------------------------------------------------------------

Haden Guest 6:09

Is the mic on? I wanted to thank you so much for this wonderful film. And I thought we could start with a little bit of a conversation here before taking questions from the audience. And so maybe just ask what happened in the thirteen years that led you to such a different concept of what a documentary could and perhaps should be? Because this is a film that is as much, I think, about an interrogation of the documentary, as a form, as a possibility, as a set of limits, as well as it is a film about Santiago. And I ask that recognizing as well, that you have a career to and documentary that preceded this film as well.

João Moreira Salles 7:03

I think I've aged and I've aged in a very particular moment in my life. So I was thirty-two, I think when I shot Santiago. I tried to put the film together, I couldn't. And then I just left it on the side. And when I went back to the film, I was in my early-to-mid-forties. And I think there's a big change when you’re in your early thirties and then you're in your mid-forties... One of the things that happened is that you start to realize.... Santiago's subject is time, the passing of time, memory, the death of things, and he equates death with forgetfulness. I mean, as long as you remember, you will not die; it's kind of a Greek idea. You sing the name of the hero and the hero is alive in Homer. And I think that Santiago had some conception—which was not very different from this one—when he was reading the names out loud, which he actually did, of the list of kings and princes and queens. For him, it was a way of keeping them there next to him in a very concrete way. This has to do with death and the conscience of death. When you're in your early thirties, I think you have maybe an intellectual idea of what that is, but it’s not inside of you. It doesn't run through your body. When you turn forty, you start to understand that in a different way. So I think that this was crucial. But not only that. This is a period of time, early thirties up to the forties, when I got to know Coutinho, Eduardo Coutinho, my great friend, and arguably the most important filmmaker in Brazil for the past fifty years. We have very, very good filmmakers, but I think he was probably the most original one. He invented something new that didn't exist before, and he was a documentary filmmaker. And, my relationship to Coutinho was very important to me. And one of the things that I understood through my friendship and by becoming his producer—producer of his films—is that when you start in the career, when you start as a nonfiction filmmaker, it's very common for you to think that the film is the subject. You have a subject, and that's enough. And the form, you just use one that's already there and Coutinho, that's his originality, he understood that form was as important as a subject. That is, it's not only what you say, but it's the way you say it. And that is the true, I think, contribution of documentary to the history of cinema: an exercise in form, expanding the possibilities of film, expanding the possibilities of what you can do with cinematic language.

And so that became very important to me. And suddenly, I went back to the images I had shot thirteen years before, and my images had become archival footage, because there was a distance and I could see them with other eyes, and I could be critical of the image, not to take it at face value, trying to understand was what was happening. Why did I shoot the way I shot? Why did I frame the way I framed? Why the distance? Why a tripod? Why is Santiago always in another room? The tripod is in one place, he's in another. This is the type of thing that wouldn't even be in my frame of mind. But when I began to look at documentaries—not in a naive way, believing in the image, of what the image is there's trying to say to me—but interrogating the image and trying to see what lies behind the image and in the decisions that lead that image to be the way it is. That's when Santiago became possible because that's when I discovered also something so... time, a critical view of the documentary. A documentary that has to be critical of its own form, of its own making. And then there’s a third thing. Brazilians—might be some Brazilians here. I know there are. They might understand—so what is documentary filmmaking in Brazil? As in all parts of the world, mostly, they’re films of people who have the access to the means of production. And remember, this is the 90s. Means of production were very, very expensive. Yeah, filming those who do not have the means of production. So in a sense, it starts with Flaherty. It starts, of course, and then it becomes a trope of documentary back in the 30s with the British social movement, the film in English Grierson and his school in which you go and you film, those who are on the side of, not of privilege, but of suffering, not of power, but of powerlessness. And in Brazil, this is basically the whole or almost the whole menu of films. Some of them, really very good, some of them, well-intentioned, most of them done by progressive filmmakers. But yet, there is an imbalance. In the sense that because you are who you are, from the social class you belong to, you know that you'll be able to gain access to, for instance, a favela and you will be able to film them, or you go to the Northeast of Brazil, and you'll be able to film hunger or disease. And of course, you cannot reverse this equation. It's very hard, not to say, impossible for someone from the favela, from a poor neighborhood, to

go into your house, your own middle class, upper middle class, white neighborhood, in Rio, San Paolo, whatever, just knock on your door and say, “Well, we're from Pavãozinho or a poor neighborhood, and we would love to see how you guys live. So we would like to stay here for a whole week filming. We will not bother you. We will not be intrusive. But we really would love to do a film about you.” And I've done those films. I have done a film on violence Rio in which I spend some time in a favela. These are the films that are made in Brazil, in France, in England, in the States, I mean, you know the kind of film that I'm talking about.

And that became with time a problem… for me. I don't think it's a problem for documentary. Each documentary filmmaker has to come to his or her own conclusion. For me it became a problem. And I realized that there was one thing that I could do, which was to turn the camera into my social class, which is not seen on the screens. It's very protective, doesn't show itself. It doesn't allow cameras to enter. And, the crisis I was going through in my 40s, when I decided to do the film, had to do with all of that. I mean, I didn't believe in the conventions I was making. I didn't like things that I was making. I didn't want to do another film on violence. I didn't want to do another film on why. Why another one? Why naturalise the idea of violence in poor neighborhoods in Brazil, for instance, which is a problem of Brazilian cinema, I think. And, so therefore, when I went back to the material, these things were not very clear; it became clear while doing the film. I realized that there was something there that was if the raw footage had something that I could say, was truthful, was my relationship to him during those five days, and it entailed, I think, sincere affection, curiosity, love, but also power. And that's when the film became possible.

So it's a film about the film. It's a film about documentary, it's a film about the possibilities of documentary, I think. It's a film that criticizes the film itself. And it tells a better story than the one I was trying to tell thirteen years before in which you would only see Santiago, you would not hear my voice. You would not see me. You would not hear me. And Santiago would be someone entirely constructed by an outside force—me—but in a very invisible and cunning way. And, the only thing that I can say for myself, is that I realized that the film I was trying to make. back in my early thirtiess was a bad film. I didn't know why. I didn't know why it was not truth. But I knew it was not. I knew that I wasn't able to grasp Santiago. Santiago was not there on the screen. And so the only thing I can say for me as a good thing is that I decided to abandon the film. I didn't try to push it, like ram it through and this is the film and this is it. So long answer, but it wasn't a simple one thing, it was a lot of things together.

Haden Guest 20:08

And yet the film is a meditation, a critique, but also a meditation on documentary, the ways in which it reveals the artifice, the constructed nature, right? The scripting and direction behind the film, on the edges of the film. It also speaks to the need for a kind of artifice. I feel like Santiago's language itself, chameleon-like blend going from Spanish to Portuguese, to Italian to Latin. There’s the story of him dressing in the tail coat in the middle of the night… There’s this performative dimension, which seems to go even beyond him as an actor in this film, and that also goes into his history of all these, you know, where the actors and the kings are one, so it seems like the film is also presenting this idea though of the need for a kind of fictive, performative world of artifice. And then when you give us this wonderful transition from walking to dancing from The Band Wagon that too seems to affirm that—which in that form is a purely cinematic, is a necessity, is a kind of sustenance as well.

João Moreira Salles 21:44

I think you're right. So I was coming from the tradition of direct cinema. Direct cinema was invented here in the United States by journalists in the 1960s. I think it's a very powerful cinema, but yet it is open to critique, I think, and direct cinema—for those who do not know what it is— journalists decided to see if they could actually film in a way in which they would not be obtrusive, and they thought naively that you could actually film life as life would occur even if a camera was not there looking at it. So they devised a lot of very intelligent and cunning strategies in order to do so. Lightweight camera and you can move with your character. You don't ask your character to speak to you, you just follow what he's doing or her—usually it's a his in the beginning. The first film is on Kennedy and Humphrey, Primary, the election in 1960. And, they film a lot during a ;ong period of time. And I truly believe that when you’re filming for an extended period of time, you actually lose the conscience of the camera. And at some point, you actually are acting the way you would if the camera was not there. The point is, this is not better than the artifice. Not at all. And then I transition from that influence to cinema verité, the Jean Rouch school. He was an anthropologist, of course, and then he was very concerned about how you portray the Other. And Jean Rouch used to say something that I truly believe is profound in documentary. He would say the following, “Of course, when you put a camera, people will act. They will perform. And you have to accept that performance.” And he would say, “It's not a matter of truth or theater. It's truth and theater.” The way you decide to present yourself, tell something which is deep about yourself, the mask you choose for yourself is very sincere, and it tells a certain deep truth about yourself. So Santiago does that to perfection. He is a performer. There is a [performance] but it is a completely sincere performance. And through that performance, he was able I think, to do something that some of the people who lived in the house and that he served weren't able to, just to find meaning and sense in life. So Santiago, [thought] of Santiago as someone who was born in the wrong century, because he thought the 20th century was the worst. He would have loved to be born in the 16th century in Italy—wrong, continent; he thought South America was like the worst. He would like to [have been] born in Europe. Wrong social class; he was born in a very small town, middle of Argentina. And he liked everything that people didn't partake. He liked opera, he liked music, he liked musicals. There was no dialogue with… And the wrong sexuality, because he was born a gay man in the early 20th century in the interior of Argentina. Think about that, how hard and yet, having been dealt the worst cards on the deck, he was able—through sheer imagination and performance—to find, I wouldn't say felicidade... I wouldn't say... How you say felicidade?

Haden Guest

Happiness.

João Moreira Salles 26:41

Happiness. Oh, God! [LAUGHS] Because it's very hard to achieve. But as he says, in a mix of Portuguese and Spanish, he was able to find contentment, joy, through the work of his imagination. And that is something that is truly touching, I think. But he did that by dancing, by actually believing that saying the names and listing the names and putting them in writing and collecting the names and taking them out to show them the light of day, and singing their names and saying their names, they would be next to him, alive. And that was a strategy of survival that brought him to what we see here, a life that was meaningful.

[SOME AUDIO MISSING]

Or I have because I was the son of his employer. In a sense always, you are the son of the employer when you do a film on somebody else. Of course, a journalist has the same power when he or she writes about someone. In the nonfiction arena, those who have the power to represent, to portray, do have the power. And that's another thing that, for me was important in the film, to bring that to... because even Jean Rouch, who thought profoundly on how to make a film that's more equal, in which you share power with your character. It is a utopia which you'll never reach. You can try. It's a horizon, you strive to go, but you'll never reach it, because at the end, it is your film, you sign it as a director, the final decision is yours. And you have to bear the responsibility of your choices. I mean, that power that you have is a part that brings with it, of course, responsibilities. And I don't think that all documentarians are aware of that. And so I think you could see Santiago also as an allegory in the sense of a documentary in which someone has the power, someone doesn't, and the film is the result of that encounter.

Haden Guest 29:49

No, absolutely. I think this is why I think this film should be necessary viewing for any student of documentary cinema, and I know there are some here in the audience tonight. So why don't we open the floor to questions or comments that you might have. And one of my colleagues in the back, if we have some water here, that would be great. Thank you.

Audience 1 30:14

Thank you so much. And so I wanted to ask you about the narration of this film also, in comparison to The Intense Now. Maybe In the Intense Now could be talked about tomorrow after... Yeah, because I remember one time, we were talking and there was a girl, she was asking about the narration of the film, and it's the first time that I hear Santiago in English because I saw it in Brazil when it was narrated by your brother and not with your voice. And if you could tell us a bit about the choice of not being your voice narrating the voiceover in the first person and then the choice maybe for The Intense Now later, maybe tomorrow, I don't know. Thank you.

João Moreira Salles

Yeah, so the film exists in a Portuguese narration, of course, and in English. Now I think that I made a mistake in having an English narration. But at the time, I was convinced that it was important for festivals here in the United States, etc. And also for audiences here because that people tend to prefer not to read subtitles. I don't know if that's true. I mean, I was convinced. And of course, in a venue like this one, it would make more sense. And it's not the archive’s fault that we sent this copy, but it's the only one we have in the US that can be screened. So that's why we have this one. It's a consequence of the bad choice I made like ten years ago. And I also should apologize because at the end, when I entered the film, I saw that it was out of sync...

Haden Guest 32:03

It slipped out of sync a little towards the end...

João Moreira Salles 32:04

It happens with digital. That's why we love analog. But anyway, in Portuguese, the film is narrated by my brother, by my elder brother, Fernando. And people tend to ask me why didn't I narrate the film myself? Two reasons for that. One is simple, but true. The other one is a little bit more complex, and it's also true, but it came afterwards. The first one was that I don't like my voice. And I wouldn't like to have to watch the film over and over again.

Haden Guest

[LAUGHING] Nobody likes their voice!

João Moreira Salles

Yeah, with my voice. That was the easy decision. I don't want to hear my voice. But then when Fernando—who has a beautiful voice—narrated the film, I thought it was a good decision. And I will tell you why. Because as Haden was saying, the film tries to explore the artifice in documentary, the fact that you should not go to see a nonfiction film in order to find truth as it is. I mean, it is a construction. And as in any construction, it is a version of reality. It is a version of what you have seen. It's not a lie, but there are other versions that could bring different or even opposite points of view. So when I introduced the voice of my brother, there's another layer of confusion that is introduced in the film, in a sense that my brother lived in that house, he knew Santiago, he had many of the same experiences. So in a sense, he's able to say what I wrote, but they're not exactly his experiences, his memories. Some of them are, some—which you will never know. And so there is also this dubious thing that happened when you hear my brother's voice in which he's telling the truth, but there’s some artificiality in the sense that he's using the first person pronoun—which is me—and so, I think it was a good decision in that sense and so, I prefer the Brazilian version also because of that.

Haden Guest 35:00

Question right here. Steven. Mariano.

Audience 2 35:10

Thank you very much. That was fantastic. And actually had the same question as [?Ana Paula?], but I have another question about form. And I actually thought there were two moments, two scenes, that I was technically amazed, which is the scene of the boxer, and the scene of the dancing hands, which is so difficult to film rapid movement. And I wanted you to say something more about those two scenes that I find very similar, both in choreographic and technical terms. And I thought they were highly poetic in the way that you decided to film and so if you can say something more about that?

João Moreira Salles 36:10

Yes, I think I spent five days inside Santiago's apartment, and then I went to a studio and I filmed what is very typical of the documentary filmmaking I was doing at the time, which is to illustrate.

Haden Guest

B roll.

João Moreira Salles

Yeah, the B roll. So you want to illustrate. You don't have the faith that the word itself is sufficient. Just looking at him, just so beautiful, saying what he says. No, you have to introduce beauty and diversion, and you have to distract the audience. Because there's a lack of faith in what you’re filming, and there's a lack of faith in you. And so therefore, I have to distract you. And the more beautiful the distraction is, the easiest it will be to seduce you. So I think that the whole film might be too beautiful in that sense, because I was not looking for truth, I was looking for something that was really formally exquisite, which is not the same thing. Beauty and truth aren’t the same thing. I've learned that Keats is here, right? [LAUGHS] So yeah, so truth and beauty, beauty and truth, I believe in that, but elegance, style are different things. There are lesser things I think. And in the film, that was very important to me. I was operating in a kind of dictatorship of exquisiteness and so, the boxer... I mean, you shoot the thing not with a wide lens but with a telephoto lens. And of course things occur very rapidly in front of the lens because using that kind of lens... The same with the hands. And I I think they work here because they’re not being used the way I thought of using them when I first shot them. When I first shot them, I would put the boxer underneath what Santiago was saying about boxing; it would be an illustration. Here, it becomes autonomous. It doesn't serve anything but itself. This is also something that became important for me, mainly because of my contact with Coutinho, the Brazilian filmmaker. Coutinho has invented the kind of oral film, morality and people speak to a camera. There's nothing more than that. And it's so beautiful, I cannot tell you how beautiful it is. But one of the things that he has eliminated through his work is B-shots, illustration, because it is a way of saying “What you were saying to me is not enough.” I have either to prove—so someone says “When I arrived in Brazil coming from Argentina, I came via boats,” and then you have to show The image of the boats arriving at the port. This is evidence, the moment you do that, you’re saying “I doubt your words” and therefore improving what you're saying is truth. Now, that has become a no-no for me because I'm not a journalist when I'm a documentary filmmaker; I don't have to go after evidence. For me, the important thing is—in a film such as that one or of all the films of Coutinho—is how is the person being filmed able to transmit an experience? And if that is successful, that is the truth I want. Memory, time, someone like Santiago—he was eighty-something when I filmed him—of course, he will not say the facts. Because the work of memory is the work of construction. You forget, you add, you mix things—not out of bad faith. It's not mythomania; it's the way memory works. Right? And because this is what interests me, I'm not looking for illustrations to prove. I want the person to believe in what the person is saying. Truly believe. Even if it didn't occur exactly the way it is– That's where documentaries for me diverge from journalism. You cannot work like that as a journalist, but you should and you can work like that as a documentary filmmaker, in which you are trying not to seek facts, but between parts, transmit an experience, and those two things are not the same. So Santiago is a film in which all the B-shots were meant for a purpose, which I think is poor, is not an intelligent way. It's a very, very pedestrian way of making a film. Things have to gain autonomy. An image should not serve as an illustration of something else. And someone should not be confronted with the proof or the lack of proof of what the person is saying. So this is why the film is– All of that was a slow learning, I think, and so I wouldn't be able to make that film when I shot that film.

Haden Guest 43:18

As it is now, the two moments of the hand, they are autonomous. They're almost films within a film, which I think also brings a different beauty to them.

João Moreira Salles 43:27

And I think they’re a moment of beauty that Santiago gives as a gift. It's a gift because I agree with you. It is beautiful, not because it is shot beautifully, but I think the thing itself is really beautiful. And he knew he was being filmed and he knew how to act as someone being filmed. Although it was the first time that he was filmed, he was a born actor, and therefore there's an encounter of someone who was born to be filmed with a camera who loves filming him.

Audience 3 44:16

To follow up on what you just said, I’m curious about your technique now on the, I think, exquisitely beautiful extreme close-ups of the text and extreme close-ups of the closed text with the ribbons. So many of them and then of course the close-up, close-up text and the absurdity, my imagination to think that he typed these out and so what I'm curious about what your take is is that they seem like... You earlier said that you regret no close-ups or no varying your shots; you have this sort of distanced view which was very Vermeer-like though, I must say. I thought extremely Vermeer and painterly to be shooting from another room. It was quite beautiful, but was it a regret on your part for not having any close-ups of Santiago?

And so the close-ups of the text to me was an apology. It was kind of a portrait of Santiago. I didn't feel like they were too exquisite or too precious. I felt like they were honoring him because they were of his hand. So if you could address your take on that, now. Does that make sense?

João Moreira Salles 45:28

No, it makes sense now. I never thought of that. But it is an apology, but a late apology. It's the only thing that I shot when I went back to the film. Yeah, yeah, yeah. So only two things were shot, after I decided to go back to the film: his papers—close-up of his papers—and when he tells the story of, of the Divine Comedy, in which you see a plastic paper flying, that was shot also, afterwards. The only two things, and so as I couldn't go back and shoot Santiago from up close, that was the only thing that I could do, to shoot up close his life's work.

Audience 3 46:36

Sorry, so a follow-up on what you just said. There is another moment in the film that I actually felt the power shift, and that was when Santiago's calling you to save his papers. And so did you and where are they and what are you going to do with them?

João Moreira Salles 46:57

They are saved [LAUGHS] and they are housed in the house because the house now is a public institution. It's a museum and it it is an institution which houses archives. So it has the largest private collection of photography in Brazil for researchers and also of music. And it has also Santiago’s papers. They are there for anyone who wants to see them or research them. In fact, there's a brilliant—she's not a student anymore. She just got her PhD from Brown—Flora. I don't know if Bruno is here but Flora—Brown is there. Yeah. Flora, I met her at Princeton. And I think that's where she saw the film, and she was fascinated not by the film but by Santiago. And she's writing about Santiago and she's using his papers. She's American. But she became a Brazilian.

Haden Guest 48:09

Well, I want to say what a wonderful evening this has been but there will be more tomorrow's João Moreira Salles will be back for In the Intense Now tomorrow night at seven, and he’ll be in conversation with Mariano Siskind and Bruno Carvalho and so I ask you all to please come back tomorrow night. And now please join me in thanking João Moreira Salles.

João Moreira Salles

Thank you very much. Muito obrigado.

[APPLAUSE]

©Harvard Film Archive

Related film series

Explore more conversations

Kenneth Anger

João Pedro Rodrigues & João Rui Guerra da Mata