Short works by Shirley Clarke introduction and post-screening discussion with David Pendleton and distributor Dennis Doros.

Transcript

John Quackenbush 0:01

March 23, 2015. The Harvard Film Archive screened short works by Shirley Clarke. This is the audio recording of the introduction and discussion that followed. Participating are Dennis Doros from Milestone Films and David Pendleton, HFA programmer.

David Pendleton 0:18

[INITIAL AUDIO MISSING ]--figure in what's often called the New American Cinema, mostly focused on the 1960s, alongside people like John Cassavetes. But much like Jonas Mekas, who's also remembered as one of those people, she also deserves to be remembered as part of the American avant-garde, especially once we consider her short work. She began making short films in the early 1950s, when she began making films, and continued throughout the 1960s and 70s. One of the things that she was doing in the break between Portrait of Jason, in 1967, and Ornette: Made in America, in 1985—those being her last two feature films—was continuing to make short films, as well as video work. And a lot of this work is still not very well known. But it's getting better known, thanks to the efforts of the good people at Milestone Films. Which brings us to our special guest tonight.

Milestone is one of the most important American distributors, active since 1990. And they release, theatrically and also on home video, a lot of important independent films from the past, titles, as well as foreign films, titles like I Am Cuba, Charles Burnett’s Killer of Sheep, Murnau’s Tabu, The Exiles, On the Bowery. And the two most recent titles, I think, also indicate the good work that they do. They're working on re-releasing,Leo Hurwitz’ Strange Victory from 1948. Hurwitz being another one of these sort of almost forgotten, or semi-forgotten, independent and nonfiction, mid-century figures. And Kathleen Collins’ Losing Ground, young African-American filmmaker, this film from 1982, who, sadly, died very young. Basically Milestone Films is Amy Heller and Dennis Doros. And we're very grateful to them for all the work that they've done. Lately, they've been working on something that Dennis calls Project Shirley, which is gathering the best materials available of Shirley Clarke's work and getting it out there, working with people, with institutions, like the UCLA Film and Television Archive, that's worked on the restoration of a couple of the feature films, and particularly Shirley's personal papers, etc., that are on deposit at the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theatre Research, at Madison. So here to guide us through this program that will include nine films, we're very grateful to have Dennis Doros. We’ll watch them in groups of three, with Dennis giving us some introductory remarks between each of the three. And Dennis has also kindly agreed to come up afterwards and take questions for, from you, that you have about the program, about Shirley’s short work, etc. So please join me now in welcoming Dennis Doros.

[APPLAUSE]

Dennis Doros 3:32

Thank you very much. It's great that you came out on a cold Monday evening to see Shirley Clarke's films. Two weeks ago was my first presentation at MoMA ever, which was my local museum. Now my first time at Harvard. I feel very blessed and lucky and very thankful to David and Jeremy and Haden for having me here today. Harvard Film Archive is one of the great ones in the world and I've known them ever since Vlada Petric was in charge in the 1980s. So it's really cool to be here for the first time. Tonight's show is really special because Shirley Clarke did– I should start off with, Project Shirley came about one morning, when I just turned to my wife, Amy, and said, “How about Shirley Clarke?” And she said, “Yeah, let's do it.” I mean, people want long, involved stories. But the fact is, we run a company by whim, and after she said yes, I started worrying that maybe she's too popular. Milestone is known for bringing out films that had been forgotten to history, and when I got to New York in the 1980s, Shirley was everywhere. I never got to meet her but she was famous, she was popular. And so I started looking around to see any research about her and although there is over 100 books on Brakhage, 100 books on name any other, you know, avant-garde director of the 60s and 70s, there was nothing on Shirley Clarke. There was a third of a book by Lauren Rabinovitz on Shirley. And when I started asking students, nobody had ever heard of Shirley Clarke. And this was just, not only unbelievable to me, but exciting to me, that this is what we do. If people ask me what I'm doing, and I tell them, and they know the film, then I'm in trouble. Milestone really wants to do the films that have been lost. And so I started rounding up the feature films, which was fairly easy. Wendy Clarke, Shirley's daughter, lives in New Mexico and she was very excited. She got everybody involved. And when I got to the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, I'll be a little blue on this one, and Boston might have to arrest me. But the first thing I did was I talked to the head of Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, a woman named Max, Maxine Fleckner Ducey. And I said, “I want to go through the film archives of Shirley Clarke’s.” And she says, “It's huge, and what are you interested in?” And I paused, not knowing how to phrase this, but I said, “Well, actually, everything.” And she looked at me, and I looked back, and she said, “Well, fuck, yes!” And I think every archivist should say this. [LAUGHS] As a distributor, you don't get this too much. It's, “It's ours. You must keep away.” And Wendy Clarke and I went up to Wisconsin for a week, to look at the films, and there was a treasure. I mean, every time I had done a project before, I tried to look at every film, from Von Stroheim, he ever directed, every film of Raoul Walsh’s he ever directed. There's a lot of those.

And I got, not only to see all the films of Shirley Clarke, I got to see her outtakes, her work prints, everything. And this was like one of the greatest treasures I've ever found on any director. Her home movies date back to the 1927 Deal, New Jersey, baby parade. It was for a younger sister, so I didn't digitize that. But we digitized just about everything in the collection, to figure out what was what and how they collect, interconnected. And tonight is just some of the real highlights of what we’ve found in the last six years. We just started showing them about three, four months ago to people. And the DVD/Blu-ray coming out later in the year is gonna be eight hours, maybe more. I keep collecting and Amy keeps saying, "what are you doing?" [LAUGHS] But we're having fun. And so tonight is mostly her short films. Most of them were published; only one had not been seen before.

And the thing to know about Shirley Clarke is that she was a bad student. She was probably dyslexic. She didn't read until five or six, something like that. And she was a terrible student with terrible insecurities. And in high school, she found dance. And she fell in love. In the home movies, you can see a graceful dancer, not one with expertise. She started too late. But she loved it, she was a dancer. She went to seven colleges in her life. And I thought she was flunking out or getting thrown out. But it turned out that she would go to Stevens College in Missouri, and take three dance courses with the professor there she wanted to take courses with, then she'd go to North Carolina State, and study there with a dance professor. There was so little dance teaching in the 30s that she had to go from place to place. And when she came back to New York, she became a dancer. She became the head of the Dance Association of New York. She got to meet everybody. But by 1952, she was middle-aged. She was, for a dancer. [LAUGHS] She was 33, I have to say. But she had an eight-year-old daughter. She didn't know what to do. And her psychiatrist—who only treated artists, and he used to have art shows with his patients, very strange.—they talked it over and she had this Bolex, she always liked this 16 millimeter Bolex she had gotten for her wedding, she was doing home movies with. "Why don't I become a filmmaker?" And I have seen a lot of films by people who are saying, “I'd like to do a film!” And they are terrible. But her, from the very beginning, her outtakes, her first film, Fear Flight, was never finished. But from the first outtakes, it's like, oh my god, does she know dance! And does she know rhythm! And does she know editing. And she went from zero to 60 like nobody's business. This woman took one course with Hans Richter and what you'll see first, the first film tonight, In Paris Parks, is actually her second film. Her first was called Dance in the Sun with the dancer Daniel Nagrin. And it's a lovely film, but In Paris Parks is her second film—and it's a masterpiece—it’s just this lovely, beautiful film. The little girl with the hoop in it is Wendy Clarke, her daughter. And the second thing you'll see in this brief series is Brussels Film Loops. In 1957, the World's Fair was being held in Brussels, and it was the first Cold War World's Fair. It was the first one after World War Two and it became an ideological battle between the Soviets and the Americans. They both spent huge amounts of money trying to produce great propaganda for the World’s Fair, to show their lifestyles were better. And in the American pavilion, which was round, it had a large number of rear-view projectors encircling this round room, and each one would have a three-minute film loop of, something of America, to show how proud it is. One was called Shopping Center, one was called Occupations. And Willard Van Dyke hired D.A. Pennebaker to shoot and Shirley Clarke to edit them. And Shirley really wanted to put jazz as scores for them. And they said, “No, they're gonna be rear-view projection, in this big room, it's going to be silent.” So she said, “Hell with it, they're going to know jazz.” The editing is so beautifully on these three-minute clips that you feel the jazz, whether it's on the soundtrack or not.

And the third film is Bullfight, in 1955. This is the only film starring the great choreographer, dancer, Anna Sokolow. It's the only film of her dancing. In the outtakes, there's all these wonderful Anna Sokolow films that I am just dying to show everybody. I spent all day Friday working on a work print of a film that she never showed, just because it's Anna Sokolow. She is this magnificent woman, Martha Graham's equal to that, during that time, and still, in my mind, her equal. And you'll see the one fight they're in together. And that'll be the first three films, and I think you'll like ’em. Thanks for coming.

[APPLAUSE]

[SOUNDTRACK MUSIC IS HEARD FOR A MOMENT]

[APPLAUSE]

Dennis Doros 12:04

When I first met Amy, I took her to a lot of dance concerts. It wasn't her favorite thing but it was mine. And I have terrible face recognition. But we were in a restaurant in New York one day and here comes this fairly short, plump, pleasant looking woman. And I said, “Oh my god, Amy, that's Anna Sokolow!” And Amy knows that sometimes I can't tell my own family's faces. But Anna Sokolow is something I knew, because I just adored her work. And she was known as the “choreographers of doom.” And this certainly is reminiscent of a lot of her work. But in the outtakes of Shirley Clarke, they did a film called Rose and the Players, which was never finished. But the complete choreography is in there and it's one of the most joyous, funniest dances I've ever seen. And so Anna Sokolow did a whole lot of different things but this is the film she's known for and this is how she's remembered.

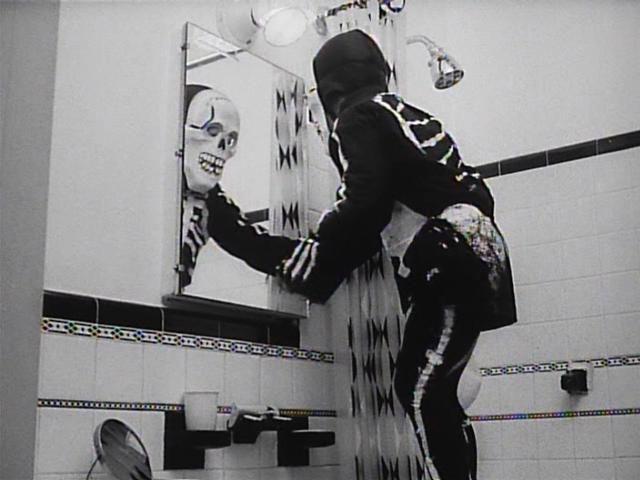

The next three films, A Scary Time, and a Shirley Clarke interview, and Bridges-Go-Round, weird combination. Scary Time, she took on a commission from the United Nations for UNICEF. And she created a film that she really felt deeply about. It was so scary and I have to warn you in advance that it was not shown for five years. It's basically about helping the poor children in third world countries. And there's a lot shown. One of the interesting things is, it's also shot in the neighborhoods. We can't decide whether it's Connecticut or Long Island. There's different memories about it. But the little kids tell you who they are, and one of them is, I'm Frazer Pennebaker! Who is D.A. Pennebaker’s son, and now, at 50, I had to call him up after seeing this film and laugh, that here he is, this gap-toothed kid, in film forever. The main star of the film is this young kid in a skeleton costume, and his name is Peter Wilcox. And I decided, I started Googling the kids’ names, and Peter Wilcox, the star of A Scary Time, turned out to be the captain of the Rainbow Warrior. And he's been one of the great ecological battlers of the 20th century and 21st century, he just came back from a year and a half imprisonment in Russia. One of the great figures in 20th century and he is a little kid starring in A Scary Time. The second thing is a television interview Shirley Clarke did in Minneapolis in 1956, which appears in her collection. Shirley Clarke is known—I love this expression by one of her mentees, “She was such an easy person to love, and such a hard person to like.” She could be a tough, tough woman because she was the only one in her field for a long time, making feature films. It was a hard battle a lot of times. But there was this wonderful, giving, terrific side of her. In this early interview of her, you can see how magnetic she is, and how shy she was, getting into film, and how tough it was to be in it. It's pretty sexist in its content.

The third film is Bridges-Go-Round, which is probably her most famous film. One of the Brussels Loops was called Bridges. And it's an earlier version of it. I didn't show it, there's 60 minutes of Brussels Loops, and we thought that'd be too much for one night. But she took this short film, three minutes, and turned it into Bridges-Go-Round. And there's two different scores. This is the one with the Teo Macero score, which she had commissioned afterwards. It’s a lovely jazz piece. But this film really dances, and it's just the bridges of New York, it's just spectacular. And so those are the next three films.

[APPLAUSE]

[MUSIC AND CHILD'S VOICE FROM FILM HEARD]

United Nations Children's Fund presents a film by Shirley Clarke.

Halloween’s a scaaaaaaary time. And it’s time for children to have ... [INAUDIBLE]

[APPLAUSE]

Dennis Doros 16:10

It's fairly safe to say that Bridges-Go-Round is one of her best-known films. It's shown, always together, not tonight, with the first score that she used. She had to show it at the Brussels World's Fair at the same time as Brussels Loops. She needed a score. She went to Louis and Bebe Barron, the early electronic music composers. And they had just done Forbidden Planet for MGM, so they gave her three minutes from their score for MGM. And since she was afraid of being sued, she got Teo to do another score. And somewhere in the 60s, somebody got the idea of showing them together, 10 years later or so. And so they showed together, but the prints were used, always used the best negative. And they put the two scores above on the same negative. When we scanned the two negatives, it turned out that they were slightly different. They were the exact running time, but the colors are different and there's little, slight differences in editing. So we now have the two original versions of Bridges-Go-Round so people can see, if they really want to be [LAUGHS] OCD like me, the differences between the two versions that she created.

As she got older, you would expect, like a lot of directors, they get a little more staid, a little more comfortable in their rhythm. They do the same films over again. And Shirley did not want to do that. She was just too tough a filmmaker and too tough on herself. And so she started experimenting, especially in the later in this, ’66-’67, when Warhol came about, she was influenced, they were friends, they saw each other's work. So the first film you'll see is 24 Frames per Second, which is a little short thing she did for the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, I think it was 1977, for a Persian art exhibit. And it's like two minutes, three minutes long. And it's exactly the right time, because the score really drives me crazy. But it shows you how brilliant she was. This is before MTV, and before quick cutting. And she did a film that is just spectacular to watch, in editing. The second film is called Butterfly. And when we were at the archives, we saw this title, and I was intrigued. It sounds like a lovely film. And I asked Wendy Clarke, her daughter, what this film is. And she said, “I don't know!” And so we started it and Wendy says, “Oh my god, I made this film with her, with mom.” And it turned out to be a film that they showed once, in January 1967. It was an anti-war night of screenings at a theater and they invited artists to bring an anti-war film. And this is the one they did for that night. It showed at this NYU, that one night, never showed again. And she was saying, “Ah, it's kind of amateurish, and all.” I said, “No, I think it's really cool!” And Mary Huelsbeck, who's now the head of the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, says, “Oh, Dennis is right. Let's watch it again.” And it's now, this is the one film, first film that Wisconsin has restored photochemically, to make sure it exists, because this is a painted on film, film that Wendy and Shirley did. And the music is by Wendy's cousin, Liza Lorwin, who was maybe seven at the time.

The third film was this whole series she did at UCLA called Four Journeys into Mystic Time. This is one of them. And by ’68, she really got into Portapak video, she was really experimenting with them. And by the time in the 1970s when she did Four Journeys into Mystic Time, she had become really brilliant at all the new video techniques, and all that. If anybody comes to see Ornette: Made in America, it's tomorrow, David? Sunday! It's gorgeous editing, it predates MTV and it's really one of the great portraits of Ornette Coleman. It's really Ornette, I have to say. But this is one she did with UCLA, with the choreographer Marion Scott. And it's really, the series itself—we're only going to show one tonight—is just amazing. And I should say, before I end, I'm trying to end quickly, so you can get to see these films, because they’re so much better than what I can describe. There'll be a Q&A afterwards if anybody has questions.

[APPLAUSE]

[MUSIC FROM SOUNDTRACK]

[APPLAUSE]

Dennis Doros 20:56

So you can see, over the years, she just kept experimenting and experimenting and experimenting, with all sorts of incredible people. Are there any questions about Project Shirley? Yes.

[INAUDIBLE AUDIENCE QUESTION]

Dennis Doros 21:18

No, there's really no history of it. It was a really, a pet project. There's actually a video of three variations, I call it, of 24 Frames per Second, where she converted it to video and had dance performers over it, much like ONE-TWO-THREE. And it got really bizarre. But this was a project that Ron Haver, at the LA County Museum of Art, commissioned her to do and there's not much history about this. She was doing, she was teaching at UCLA at the time. And so there's not much record, other than let's do the film. Yes.

[INAUDIBLE AUDIENCE QUESTION]

Dennis Doros 22:01

It's really, the easiest answer is sexism. I mean, that's the answer, is that she wasn't as charming, she wasn't, whatever. I mean, people treated the avant-garde directors of the 60s and 70s as more important. Maybe because she did feature films and some people thought she sold out, though I have to say, if anybody has seen The Connection, Cool World, Portrait of Jason, and Ornette, none of them can be considered selling out. She was interested in outsider, people on the outside of society. She was born into an extraordinarily rich family. Her grandfather invented the self-tapping screw, which, unless you're an engineer, you don't know the significance of it in the 20th century. But she grew up dyslexic. She grew up as the stupid kid. She was Jewish. And so in New York society, she was always the outsider. And she was attracted to the outsider, especially jazz music. She loved jazz music from the very first, and Felix the Cat. She had a Felix the Cat cartoon in 1929. She bought it, it's gonna be on the DVD. And she had a 16 millimeter projector, and she would run this film over and over again, dressed as Felix the Cat. But in terms of—you know, you can go back and say, "Why did you never write about Shirley Clarke? Why has Kathleen Collins never been distributed before?" A lot of the things we do... Strange Victory hasn't been distributed, ever. Except by the producer, Barney Rosset, in ’48. There's really no rhyme or reason why things attract critics, why they attract historians. Amy's line is, Milestone is there to fuck around with the canon and adding films to the canon. And Shirley Clarke is a really easy one. Larry Kardish, who was the head curator at the Museum of Modern Art, his very first job was working with Shirley distributing Portrait of Jason, when he just came out of Columbia University. So he's writing the first biography of Shirley. And he's finding, I mean, she was a very deep, very troubled and happy person at the same time. So it's going to be an incredible biography of her. So I'm looking forward to it. He's finding out things I didn't know about.

[INAUDIBLE AUDIENCE QUESTION]

Dennis Doros 24:37

I honestly don't know. The man who would know is Frederick Wiseman, who lives around the corner, whose company’s around the corner, Zipporah Films. He produced the film. He had actually invested in The Connection and wanted to make films. And so he thought the best way would [be to produce] a film. So he produced The Cool World. He owns the rights to it. And I would guess, it's a real city film, and a lot of the cities identified with it, and maybe it programmed a niche. Maybe it was cheap. They did show a lot of interesting films in the 60s, people don't remember. But honestly, why that one film, probably because the distributor had a collection that they sold around the country. It was just easy to show. Yeah, it hasn't shown in a long time on television. Nor did any of the other Shirley Clarkes. Portrait of Jason has never shown on television, it will on–

[INAUDIBLE AUDIENCE QUESTION]

Dennis Doros 25:35

No. The Connection never did either, for obvious reasons. it was banned originally. They will be showing on TCM later this year. They actually were a major supporter of this project early on, from day one. Yes.

[INAUDIBLE AUDIENCE QUESTION]

Dennis Doros 25:51

She was there for almost everything, first of all. She was the beloved only child. And Shirley adored Wendy. We didn't much talk about that because she was there as support. She wasn't there working. What I found really interesting is that Wendy has become a great video artist and fine artist, over the years. She did these things called the Love Tapes, where a person goes into a room—I'll do this very quickly—and talks about what they think of love in a span of three minutes and twenty seconds. And she's done over two thousands of these. After coming back from the Archive walking back to the hotel, we found out so much about each other. She said, “You know, the difference between my mother and I is, she was always the center of the room. She was the center of the universe. Everybody circled around my mother.” And her films, and Shirley’s films are very extroverted. You can almost call them macho, in fact. I was thinking about some of these films are really tough films, really beautifully made films, that you wouldn't identify the gender of the director. I think that would be her best compliment. She didn't want to be known as the best woman director, she wanted to be known as one of the best directors. And so her films were very extroverted. And Wendy said, “You know, I'm a listener, and all my films are about listening.” And so there's the major difference. If you think about Shirley Clarke, they're very extroverted, very in-your-face films, and identified with people who are not people you see on the street all the time. Any other questions? Okay, well... Oh!

[INAUDIBLE AUDIENCE QUESTION]

Dennis Doros 27:42

Well, she was best friends with D.A. Pennebaker and Ricky Leacock. They shared offices together in the 50s. And Pennebaker still speaks of her as one of his best friends. She admired them, and loved them, and made fun of them in The Connection—and her—and Portrait of Jason. She thought cinema verité was, in theory, bullshit. [LAUGHS] But she loved the films. But the funny thing about Shirley Clarke is she adored Fred. As I said, Felix the Cat, but she loved Fred Astaire. She loved classic Hollywood. She was not somebody who thought that was beneath her or anything else. She would have loved to have done those films if given the opportunity. I don't think she could have made ’em, she's just too experimental. But the other nice thing about her, is in 1957, a young kid says, “I want to make a film.” They talked. She lent him all her equipment, which was expensive at that time, and she didn't have money. And it turned out to be John Cassavetes. And it was his first film, that she gave, donated, all the equipment to make it. There's just biting commentary she could make about people, at the same time, such generous acts, all through her life, for people. She lived in the Hotel Chelsea, which in New York, on West 23rd Street, was started off as this very socialist, commune-like hotel, where all artists could afford to live and work. And for 100 years, until recently, artists did. And she was friends, best friends, with Patti Smith, and Robert Mapplethorpe, while Virgil Thompson would come by, Arthur C. Clarke. For her birthday, she lived in one of the two penthouses on top of the Hotel Chelsea, which were like these two-story concrete bunkers on the roof. So to get to her apartment, you would have to climb up to the roof, walk on the roof, which she made into a sort of garden, and then enter her apartment. So she had this outside thing for the 1965 birthday party, must have been for herself, she had the Grateful Dead perform. She knew everybody. She was friends with everybody. She was just one of the great personalities of New York. So who she was influenced was everybody she knew. Everybody she was working with. Harry Smith was one of her best friends. Everybody fed off her and she fed off everybody. It was one of those great times in New York, which I think is every year. [LAUGHS]. It's just one of those great things about her. She did learn from everybody so quickly. Yes.

Audience 1 30:27

Wasn't there a great deal going on in Europe at the time? And was she aware of what was going on?

Dennis Doros 30:32

She was, I mean, she saw everything. I mean, you know, you read her letters, she loved a lot of films. And I'm trying, I mean, I haven't gone through all the diaries. She must have been. I mean, it would have been ridiculous to say she wasn't, because everybody was influenced by, especially, The Bicycle Thief. Every American director after 1950 was. So you can say that she probably was but she was really influenced by herself. I mean, she came up with The Connection. Portrait of Jason is influenced by Andy Warhol, I got to say. But really, her films are like nobody else's. And I can't really see a foreign influence on her films. She was really about the people around her and about the ideas around her. So. It must have been but I don't know any specifics. One of the things I should mention also is Bert Clarke. She married him to get out of a horrible family situation. Her had gone broke over the Depression, had become fairly brutal on the kids, beating them pretty– Especially since two of the three were rebellious daughters. It was a very tough teenagehood for her, so she married young. And she said she married to escape, but she married this incredible man, Bert Clarke, who, I believe, was, in the honeymoon and in the photos he was in, I think he was Coast Guard. But some kind of sea uniform. Very handsome, very elegant man. He had an extreme influence on her as well. He was her cameraman for the early films. Remarkable taste. Pennebaker was best friends with him. He really helped her in her career, but at the same time, she remained independent of everybody. I mean, she really had a force of nature about that she knew what she wanted to get done. So Bert was very important to her technically, very important as a partner in crime. And I, and partly, probably I'm saying this because my wife, Amy Heller, president of Milestone, is not here. And I feel like she should be here too. But Bert was this remarkable man, she left him for Carl Lee in ’61, who was the star of The Connection. But if you see the Clarke family, Martha Clarke, the founder of Pilobolus and all that, incredible artistic family, too. So there was a large influence by her husband and the ideas that he brought into it as well. He was a very remarkable man, one of the people I just can't stop reading about, when I see the letters and all.

Audience 2 33:24

So you mentioned that she was at the forefront, sort of, of the video making, after doing so many wonderful films. And I'm wondering, did she completely depart from film at that time, and go straight into the experimental video? Or did she continue to work with both mediums?

Dennis Doros 33:44

It's a difficult answer. She started working on video, I think, as early as 1967 she got her first Sony half-inch Portapak. And she found it fascinating. Must have been ’68, because Portrait of Jason came out in ’67. She found filmmaking, making features, more and more difficult to finance. Her films never made money. I mean, Portrait of Jason was her biggest hit, and it lost like $40,000 in New York after playing seven, eight weeks. And it was a big hit. So she was getting difficulty financing. She was doing a film about Ornette Coleman as early as 1967. Denardo Coleman, Ornette’s son, is like eight, nine years old, and starting as a drummer for the Coleman band and she was fascinated by this. So she started making a film but it was not finished until Ornette: Made in America, 20 years later. So she was trying to do film. She found video cheap, immediate. She loved the process. The TeePee videospace films are sometimes tough to watch, because they're an hour and a half long, and not much happens. But the process itself, the fun they had, the people they worked with, was incredible. So it was cheap. It was easy. She loved working on video, and she loved the immediacy of it. So she really did fall in love with video and did do it while she was working. She did 24 Frames per Second, she started the Ornette film. I think if people were giving her money to make film, she might have continued. But she might have said no, I'm having too much fun with video. You know, it was never tested. I don't know. But obviously, her film work was heavily influenced by video, by the time Ornette came along in ’86. One of the interesting things, I don't know if you noticed it, was ONE-TWO-THREE, which was shot on two-inch quad video and transferred to film, she called it “a film by Shirley Clarke.” She thought of it as film, even though everything was shot, and originated, and all the effects were done on video. So I don't know if she would have found a difference between the two. Any more questions? If not, it's a cold Monday night. [LAUGHS]

David Pendleton 36:10

Well, I want to emphasize something you just said in response to that question, is that I think that Ornette, what's really interesting about Ornette, and we were talking with this briefly earlier, is the way in which it really does, I think that it reveals this influence that the video art of the 80s had on Shirley Clarke. In the context of a feature film and so it's interesting fusion, I think.

Dennis Doros 36:33

Yeah, she really did fuse the two together in Ornette, in ONE-TWO-THREE, the whole Four Journeys into Mystic Time. Even 24 Frames per Second has a video feel to it, even though it was shot on film. As I said, she wasn't very good at technology but she just fell in love with it, and could use it better than just about anybody. She just had this feel for it.

David Pendleton 37:01

So if there are no more questions, I'll just remind you once again that our series concludes on Sunday, with what's the second of two screenings of Ornette, which will be preceded by Bridges-Go-Round, with the electronic version.

Dennis Doros 37:14

Oh, cool!

David Pendleton 37:15

So you'll get a chance to compare that if you didn't see it when it showed on Friday. And finally, and very importantly, I want to say thank you to all of you, and thank you very much to Dennis, and to Amy, for making this work available again.

Dennis Doros 37:26

Well and thank you all very much.

[APPLAUSE]

Thank you.

David Pendleton 37:31

Oh, you’re welcome.

©Harvard Film Archive

Related film series

Explore more conversations

Stephanie Spray & Pacho Velez

Ute Aurand

Dominga Sotomayor

Laura Huertas Millán