Detour de Force introduction and Q&A with David Pendleton, Ernst Karel and Rebecca Baron.

Transcript

John Quackenbush 0:00

December 5, 2015, the Harvard Film Archive screened Detour de Force. This is the audio recording of the introduction and discussion that followed. Participating are HFA programmer David Pendleton, and filmmakers Ernst Karel and Rebecca Baron.

David Pendleton

Good evening, folks. My name is David Pendleton. And we have an action-packed evening at the Harvard Film Archive for you, so let's get started. There's a lot going on this weekend. We had all along been planning this weekend to show some of the work of Luke Fowler, who's currently a Radcliffe fellow, and then, more recently, we realized, thanks to the good folks of the Film Study Center, that there was a workshop put together by Harvard Center for Media Practice, and the graduate students involved therein—also shepherded by the folks at the Film Study Center—that was going to be bringing Rebecca Baron who's not unknown to audiences of the HFA. We showed a program of her work a few years ago. She was a Radcliffe fellow, she's taught here, and she also had an installation. Her installation Lossless was up in the Sert Gallery a few years ago.

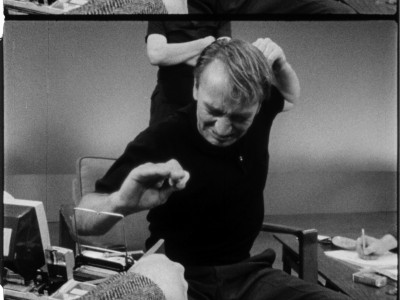

She's made a remarkable new film called Detour de Force, which also has really fascinating resonances with Luke Fowler, his work, so I encourage all of you to stick around. And Rebecca very kindly agreed to let us show it. And we'll have a very brief Q&A afterwards, because we don't have a lot of time. The film itself is, in a way, rather self-explanatory, I'll just say that it’s Rebecca working with archival footage of a man named Ted Serios, who lived in Chicago, worked as a bellhop and claimed to be able to project images onto Polaroid film through the force of his willpower, or his mind. Ted and his photographs were well-documented at the time. Rebecca has dug into the archive and put together a really fascinating presentation of this work that opens up all kinds of questions that resonate with a lot of Rebecca's other work, questions about photography, the transition from the still image to the moving image, from past to present, from analog to digital, the questions of technology and history, all kinds of stuff that you'll pick up on naturally. And that Rebecca will be here to talk with you about briefly afterwards, along with Ernst Karel, the sound designer par excellence, who worked on the film, and who's also part of the Film Study Center, and who will be up here with Rebecca, as well to for a brief Q&A after the film, which lasts half an hour. And so now, we're going to start. Thanks.

[APPLAUSE]

John Quackenbush 2:57

And now David Pendleton.

David Pendleton 3:00

Please welcome Rebecca Baron and Ernst Karel.

[APPLAUSE]

Because time is so short... Do either you have anything introductory that you want to say? Or should we ask the audience right away? I mean, I could sort of tee up a kind of thing. But if anybody's got questions for the makers, I encourage you to ask them.

Alright. Well, there's a lot to talk about... Yes. There's a question from... Luke Fowler.

Luke Fowler

[INAUDIBLE]

David Pendleton

The question was, how did you come across this figure of Ted Serios?

Rebecca Baron 3:59

He's somewhat known. I came across him because my husband grew up in Denver, and remembered seeing bits of the local television affiliate’s film about him late at night on television. And the Polaroids have been exhibited and written about a bit. There was a survey of the history of spirit photography that the Met had a number of years ago. And some of his images were in that show, and I actually can't remember why we started talking about him, but I did a little bit of research and realize that all the materials, the research about him and all the Polaroids were at the University of Maryland. I'm from Baltimore, so I was visiting and I thought I'd just go have a peek at what was there and there was this wonderful collection of 16 millimeter films, as well as all the other research materials and the Polaroids themselves.

David Pendleton 5:01

Some of the footage seems to be like kinescopes from television, in other words, originally television footage and the rest of it was film…

Rebecca Baron 5:09

Right, there's actually some kinescope material. There's actually some early video that has been put onto 16 millimeter. So it's a really particular moment in the development of these technologies. And Polaroid had been around for a while. But I feel like Polaroid is as much the star of the show and some of the materialists as Ted Serios. And the 16 millimeter camera is so insistent on featuring the Polaroid itself. It’s kind of displayed in this really prominent way, and that was part of it for me two

David Pendleton 5:46

Other questions from the audience? Yeah, go ahead.

Audience 1

[INAUDIBLE]

Rebecca Baron 5:54

He was only able to produce the images for about four years. He lived with the Eisenbud family for a while. It was extremely disruptive, as you can imagine. They [INAUDIBLE, but set up a small trust, I think, to kind of keep him going. But I think he lived pretty marginally. I think he died in 2006. There's some interview material with him towards the end of his life that I thought about including but I realized it really wasn't about the end, it was about this idea that it was just going on. But it didn't look like he was in very good health. And I think he lived a pretty marginal life. I don't know a lot of detail.

David Pendleton 6:52

If you look online, you can find a lot of things about people explaining what– But I didn't research enough to know, is there really an explanation? Like, has he been debunked? Or is there still some controversy about exactly how he did what he did?

Rebecca Barron 7:09

Definitely there’s debunkers and there are believers and you can go on Wikipedia and read about how he's been debunked, and probably have your own ideas about that. You may or may not. But no one was actually ever able to reproduce what he did. And many people I encountered in doing the research, absolutely stand by Ted Serios. I met a number of people who witnessed him making these images. And I knew the film wasn't about that. For me, it is not. But sure, of course, everybody wants to know. [LAUGHS]

David Pendleton 7:48

Right. Yeah, I was interested to hear you talking about how you felt about that approach to it. Because there's a way in which this is a particular approach to history, or to telling a piece of history in a way too. I mean, taking footage from the archive and then doing certain things with it and not doing certain things with it.

Rebecca Baron 8:07

Right. I was so enchanted with the materials. And I felt like so much of it, for me was about trying to evoke that experience in the film itself. So it's edited, but I tried to maintain the feel of the materials as I found them.

David Pendleton 8:25

I mean, one of the things that I think is so remarkable about the film is the way in which it reconciles or it’s both about, but also doing this thing of reconciling the belief in magic or wanting to believe in a certain kind of magic and image-making technology.

Rebecca Baron 8:44

I mean, photography is kind of magical still to me, and I felt like the relationship between the paranormal and sleight of hand was much closer than I originally thought. So they became very close together rather than further apart.

David Pendleton 9:04

And what do you mean by that? That, in other words, sleight of hand can produce the paranormal in some ways, or…?

Rebecca Baron 9:12

I think it's so much about experience. It's experiencing something with your senses. And I think even if we're witnessing a magic trick, we know there's a trick but the experience of it is still magical. So I feel like the experience of witnessing Ted Serios making these images no matter how many times you watch that transmission, whatever it is happening, it still produces the images and you can't see how, so... yeah.

David Pendleton 9:44

Right. Oh, sorry. Yes.

[INAUDIBLE AUDIENCE QUESTION]

Rebecca Baron 9:58

It was an unusual process. I had some tracks that Ernst and Kyle and Guiseppe had recorded together and I was using them to edit with, and then I got really attached to them and started kind of messing with them. And I asked Ernst to have a listen and share what I'd done with the other musicians, and it turned it into a collaboration and a bit of a negotiation, too. But we'd worked together before and it was an easy dialogue. And I don't know if you want to say more about it? It was really unusual, because we were on opposite coasts. And we did everything over the Internet, over the network, which I wouldn't do again. It worked really well actually, but it would have been nice to be in the same space. Do you want to talk more…?

Ernst Karl 10:55

Yeah, so it's interesting, you know. Rebecca sent me the version that had this music in it. And so I kind of felt like—I mean, I loved it—but I felt like if it was going to happen, then I wanted to do the mix myself with the other sound and sort of manage how that was going to happen. But the sound design was basically done by Rebecca. I just did some kind of fine-tuning.

Rebecca Baron 11:23

I should mention, he added more humor to the piece. I think there are little tiny details that were [INAUDIBLE] which I love. [LAUGHS]

David Pendleton 11:38

There was somebody who had a question…

[INAUDIBLE AUDIENCE QUESTION]

Rebecca Baron 11:47

I had a lot of picture without sound and sound without picture. I had this audio cassette tape. So for me, it also became a game in a way about... and this obsession with synchronization that they keep talking about.

Ernst Karel

That's the ongoing joke. That was your joke, though.

Rebecca Baron 12:04

Yeah, no, that was my joke. I just found that irresistible.

[INAUDIBLE QUESTION]

Rebecca Baron

Yeah, there's a shot of actually my hand holding it. And so there was a little Ziploc baggie with five or six of them.

[INAUDIBLE AUDIENCE QUESTION]

Rebecca Baron

So it's just the black paper that was around the Polaroid rolls at the time. So they would just peel them off the roll, and then make the gizmo out of them.

[INAUDIBLE AUDIENCE QUESTION]

Ernst Karel 13:08

I mean, I use the word joke slightly facetiously. But I mean, the thing about synchronization… He says, “You couldn't get much more perfect synchronization than that.” That's what I kind of find humorous. But that's not laughing at the subject matter at all.

Rebecca Baron 13:26

Yeah, for me, either. I mean, I think for me, the film is a lot about desire and photography and belief and the kind of intensity around that that is on the faces of those people in the room. And, sometimes it's the desire for this thing to happen. And sometimes it's the desire for it not to happen. And that tension is so palpable for me. The social environment is interesting. I mean, there are a lot of things in the film that are interesting to me. It's certainly not a joke for me.

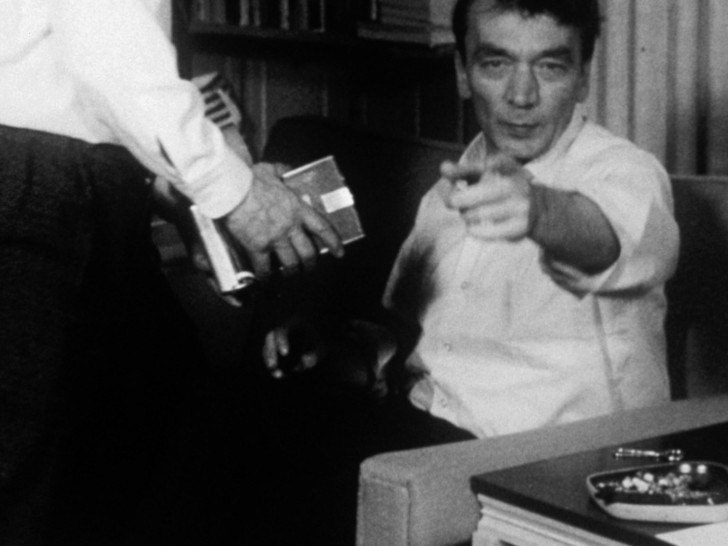

David Pendleton 14:07

That makes me think of the ways in which the film encourages us to think about Serios as maybe not a psychic, but not necessarily a conman, either. I mean, there's other ways of thinking about him. There’s almost this sort of shamanistic kind of thing about him, that he is able to induce in these people this belief in a certain kind of thing. And also as a performance artist, just that he was able to figure out that he would do this thing, and it's through the way that he moves his body and sort of concentrates that it becomes this performance and this ritual. And there is a sense of real intimacy in some of these images too, of all these guys doing this thing in the basement together, trying to make this secret thing happen, this strange thing happen.

[INAUDIBLE AUDIENCE QUESTION]

Rebecca Baron 15:13

You see it actually. It's a bus. It's kind of hard to tell it's a bus. But yeah, it's an image of a bus that you see after, when those three guys are examining it.

[INAUDIBLE AUDIENCE QUESTION]

Rebecca Baron 15:56

Well, Ted has a son, and he claims to have the same gift and believes he can make images over the network. But I couldn't track him down. So he says so, yeah.

David Pendleton 16:19

If we think in terms of magic, I mean, the fact that you guys were able to—from different coasts, work together, or some have this sort of meeting of the minds, for instance—there is a way in which there is still this idea of magic embedded even in very recent technologies.

[INAUDIBLE AUDIENCE COMMENT]

David Pendleton

Did everybody hear the question or the comment in the back? Okay.

Rebecca Baron 17:29

So Stephanie asked how– Originally I tried to make the film only out of the living room material and the audio cassette and at a certain point, I realized there was too much that was unclear. Some people weren't at all aware what he was doing, so I decided to start there and then move into the more expository section. And then because he wasn't a magician—like a magician has to get it right every time to be believable. He just had to get it right once in a while. And so I felt like the film wasn't really about a kind of display of all of his successes, but about that tension that was always there. He was never able to produce the images in larger forums like auditoriums; it never worked. It was always in living rooms, people's homes, in laboratories. And there was very little footage that was unedited, and that was one of the camera rolls I found. And I found that because he's out of focus, and the spectators are in focus and their faces were so fascinating to me, and the fact that they leave and everything it felt like it brought back that pressure on him and so I felt like it was an important thing to include.

[INAUDIBLE AUDIENCE QUESTION]

Rebecca Baron 19:32

That’s a really good question. All the research materials are there. It’s not a film archive. So the films are kept in a temperature controlled environment, but the labeling was like totally– It was not labeled by people who knew what was in those boxes. So like a box of 16 millimeter magnetic audio tape would be labeled as video and you know, they weren't clear on what they had. If I had a lot of extra time, I would go label the stuff! [LAUGHS] But it was very straightforward otherwise. It was just cataloged by the names of things on boxes. And the stewards of the collection are totally invested in the material. And I was kind of vetted to make sure I wasn't there to make a joke film or some kind of debunking film. So that was really fascinating to me.

[INAUDIBLE AUDIENCE QUESTION]

Rebecca Baron 20:47

Yeah, I mean, what you hear mostly comes from that audio cassette except the stuff from the TV and I think they were genuinely friends, believe it or not. [LAUGHS] But they depended on each other in this kind of difficult way. And I talked quite a number of times to Jule Eisenbud’s son who talked about what it was like to live with Ted Serios, and it was just chaos. It was chaos, really chaos, and his father was constantly bribing him, cajoling, coaxing him to work, to keep to the research. And it was a really difficult relationship. And Jule Eisenbud staked his whole career on Ted Serios. He was a respected Freudian analyst and professor and this was, in some ways, his undoing. So there was a lot of pressure there. At the same time, I think that they actually were friends. I don't think it was simply that he was this kind of performing monkey for him, which I know it comes off sometimes that way, but I think there was more to it than that. Anyway, thank you so much.

[APPLAUSE]

David Pendleton 22:05

And thanks also to Ernst. So this is a little bit of an unusual evening. Those of you who are staying for Luke's show—which we hope is all of you—if you already have a ticket, you can stay here in the room if you want to and we’ll run around and collect tickets. If you don't have a ticket, you need to go outside and get one.

Also, as you'll see Luke works also with archival footage, so we may have time to come back to some of these issues with working with archival footage in the Q&A later.

©Harvard Film Archive

Related film series

Explore more conversations

Rabah Ameur-Zaïmeche

Rabah Ameur-Zaïmeche

Jenni Olson & Michael Bronski

Albert Serra