And When I Die, I Won't Stay Dead introduction and post-screening discussion with Haden Guest and Billy Woodberry.

Transcript

John Quackenbush 0:00

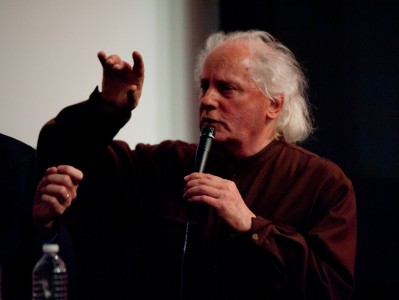

March 27, 2016, the Harvard Film Archive screened And When I Die, I Won't Stay Dead. This is the audio recording of the introduction and post-screening Q & A by HFA director Haden Guest and director Billy Woodberry.

Haden Guest 0:20

Good evening lovers of cinema and poetry. My name is Haden Guest, I'm Director of the Harvard Film Archive. And I'm really, really thrilled to welcome back to the Archive, Billy Woodberry, who was here a number of years ago—well, not that long ago, in fact—to present his quite amazing debut feature, Bless Their Little Hearts, a film from 1984 that announced Woodberry as one of the most central voices in American independent cinema, truly independent cinema, that is, cinema that was invented an extraordinary time and moment, I think, in the history of American film, and that was the LA rebellion movement, which was a gathering of African and African American filmmakers in Los Angeles, centered around UCLA that banded together to form, I think, one of the great movements in recent times in American cinema.

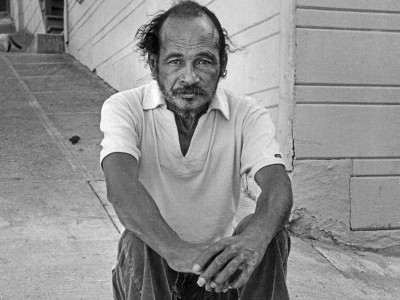

It's a film whose quiet poetry has evoked comparisons to Neorealism. And it's a film whose great subtlety and power allows it to deliver a searing indictment against racial and class inequities and yet with the subtlest of means. We've waited many years, eagerly, often and patiently for Billy Woodberry's next film. And as you'll see, tonight, it has been well worth the wait. The film is And When I Die, I Won’t Stay Dead and it's a portrait of a poet by the name of Bob Kaufman, who remains little known to those who are not specialists in the Beat movement with which he is often associated. He is an artist who poses, as you'll see, special challenges to capture. He was an artist who almost erased himself, shall we say. He was a romantic of the purest sense whose candle burned furiously from both ends. And in this film, Woodberry reveals himself to be not only an astute historian and detective, but a poet himself who's able to find ways to capture the quiksilver presence and incantatory verse that was Kaufman's great gift.

It's a lovely and quietly poetic film. And I think there’s also a great poignancy to the fact that for many of us who wondered and worried where Billy Woodberry had gone, and when we would see his next film, that he finds within Kaufman, a kindred spirit, at times, again seeming to disappear, and yet ever present. I'm so happy that Billy Woodberry is here to discuss this film with us afterwards. And now to say a few words about his new film, we have Billy Woodberry.

[APPLAUSE]

Billy Woodberry 4:13

Thank you. Thanks so much for coming. Thanks so much for your interest and curiosity about the film and your generosity being here. And I won't say so much now. Hopefully, you'll hear at the end, I'll be and we can talk and I can try to answer any questions you have. And maybe explain where I've been…. Maybe. Thank you.

[APPLAUSE]

John Quackenbush 4:48

And now Haden Guest.

Haden Guest 4:51

Please join me in welcoming back Billy Woodberry!

[APPLAUSE]

Thank you so much, Billy. That's really a wonderful film and I wanted to begin the conversation with a few questions, then we'll open the floor to questions and comments from the audience. But let's start at the beginning. like to hear how you came to Bob Kaufman, the origin of this film, which was a fire that you kindled for many years.

Billy Woodberry 5:32

I think what I'd like… Can I say something, please? I'd like to thank Haden Guest, David Pendleton, the Harvard Film Archive, the staff and all the people who have been so kind during my visit here. That's the first thing I’d like to say.

Haden Guest

Thank you.

Billy Woodberry

And I'd like to thank you for seeing the film…

Yeah, oh, I learned about Bob Kaufman… what about 1972, ‘73, something like that? A friend had his books, and she told me about the books. I read the books. I was impressed, I was impressed with what I learned about him. But I sort of put it away, I was not so knowledgeable. I was impressed, but I didn't know so much. So for a time I put it away.

And then I was in City Lights bookstore, 1986, maybe around March, and I saw a notice in this magazine Poetry Flash that he had died. And I had made the other film, Bless Their Little Hearts, and I was kind of looking for things, and I thought, Oh, I should make a film about him. And I read that article, and I read other things. And I sort of learned a bit about him. And it was a film I couldn't make at the time. So I didn't make it, I put it away. And then about 2001, 2002, it came up again. I started to think Yeah, I want to make a film about this. So I started to do the research and started to find as many things about him as I could. And I felt that I could at least try to make the film then. Before I couldn't figure out how to make it. That's pretty much how it happened. Then I spent five, six years researching. Then I spent another five, six years, tracking down people and tracking down documents and things related to him, finding as many things as I could. And then finally I started the editing process.

Haden Guest 8:09

These documents that you've discovered are really so extraordinary. And I think among them some of the most powerful of photographs that you find and to me the heart of the film—or one of the hearts of the film—this photograph taken of Bob Kaufman by his daughter. I was wondering if you could tell us about your research and your decision to give these photographs such life, such a place in the film. I mean, you use the sequence of the [?counters?] tour which I think is just brilliant. You create this film from these images, and again and again through the film the lost world of these black-and-white photographs seems to have this richness and mystery that at times goes so much beyond the present-day captured in interviews. And so I was wondering if you could speak a bit about your use of photographs and their presence in the film.

Billy Woodberry 9:04

I think they are so prominent in the film, partly it's if you think about it, not so many people had access to or used regularly motion picture cameras at the time. Fortunately, some young people did this. Footage by this man, Dion Ving, and others. That footage was rediscovered some years ago. His widow who appears in the film—she's the very daring woman with the short hair in the early part of the movie. Her name was Lauren Ving. And she gave that footage to a young filmmaker who came to her Temple of Isis to be married by her. She was a kind of priestess. And she gave this material to him and he deposited it at Pacific Film Archive, and Pacific Film Archive took it up and they also found the means to restore it. So that's why it exists. And I found it there. I knew that Bob Kaufman was in The Flower Thief by Ron Rice.

Haden Guest 10:29

He said at the beginning...

Unknown Speaker 10:31

Yeah, so, I knew there was some things. But I knew that 35 millimeter, small-format photography was very popular with people in the late 50s, 60s, 70s. It’s what they had. And they sort of documented, recorded and photographed their scene in North Beach, and their peers and these poets and people that they interacted with. So I knew something about that. And so I looked for as much material as I could that was, you know, things with him. But I believed in this, photographs... This man, Jerry Stoll, he was there since the 50s. He was a filmmaker and photographer, made a wonderful book with another poet, Connell, I think, is his name, called I Am a Lover. It was a book sort of about North Beach and about that kind of bohemian scene and all the things related to it, so I knew about that. I spoke to him before he passed away. And I knew that he probably had things and he told me he did. And I knew Chris Felver because he's an active photographer, and Nowinski and other people.

I have to say that this is not the complete credits for this film, unfortunately. So there are a lot of people I need to thank publicly. I'm thinking of Makeda Best who was a student of mine, but she also did her doctorate in Art History here. And her mother, Catherine Sneed. And the reason I mention them is they are the people who were able to find and to get for me, Kaufman's record with the San Francisco Police Department and the Sheriff's Department and to get me his mug shots. So it's very precious. And it was very helpful, because those documents then later helped me acquire through James Smethurst and another literary scholar who was doing work about the FBI and Black writers, we were able to get his FBI file from them. Because the San Francisco Police record noted that he had an FBI file. So then we had the number which made it easier to do the search. So it was like that: you follow one lead or one train of research, and then it opens up other things and you acquire other things.

You mentioned the photograph by his daughter. What happened was when I finally connected him with his first wife, the unfortunate thing, the first thing I found that connected them was the obituary of his daughter, who had died some years earlier, at about sixty-two years old or something like that. And I thought all was lost. But I kind of did research and first of all, it allowed me to contact her mother, who at eighty-three or eighty-four years old was still the president of the Retail and Wholesale Workers Union Number Three in New York City. So I called her office and I spoke to her. I was kind of passionate and bringing up things she hadn't thought of for about fifty years, right? But she was tolerant, and she told me, “Okay, right now I'm negotiating a contract. You call me back in two months, and I'll talk to you about this,” because she hadn't spoken about it. But anyway, I kept following that. And what happened was, I met the husband of the daughter, and the son, the grandson of Kaufman. And I was lucky to do that. And then I met him, he was still deeply grieving. But I met the two of them. I spent time with Michael—that’s his name. He doesn't want to be credited and all that stuff, but I insist. And they had all these photographs related to their family. And he said, “I have something special for you, Antoinette took this picture of her father.” So that's how I acquired that photograph. No one has seen it outside of the family, and she never published it or did anything. It was very personal. And there's a kind of longing. And also there's a distance and he didn't realize that she was photographing him. So I got things like that. And then also because I met the second wife, Eileen, she gave me things from their life together, you know, she gave me the picture, the photo booth with the boy, you know, precious things like that when the boy’s first born, those things, all of those things inside their life. And so once I had that, I kind of believed that I could make something meaningful in terms of images and things with those photographs. It's not original, I mean, Chris Marker… But Santiago Álvarez—the Cuban director, that famous documentarian—used to say, “Give me two photographs, a Moviola, and a bit of music, and I give you a film.”

And then because I have the good fortune of teaching in the Photo Media Program at CalArts in the art school, and I have spent twenty years with those people. And I have a kind of love for photography. I’m not a photographer, but I deeply respected and I learned a lot from them. And from Sally Stein, the historian and also my good friend, Allan Sekula. So I've been privileged to have these relations and other people in my program. I learned a lot about photography and from students, and how to use those things. So it was what I had, and it was how can I make those things? articulate? How can I make them mean, how can I make them work? But also, how do I respect the integrity of the work that went before?

The thing of the tour, I know that I had seen maybe two of those photographs and I knew Kaufman's handwriting, his printing. And I suspected there might be more, but the son of Jerry Stoll, Casey Stoll, who has his father's archive and takes care of that, we met, we talked about it. On his own, he went to search, and nd he found that his father had maybe ten proof sheets of that material, and then Casey’s mother explained to me what happened is they saw them gathering and they were at this one artist's studio, and they were making these things and they were planning this. She couldn't go because she was a graphic artist and had to go to work. And then Jerry became so captivated that he covered it like a news guy, you know, a photojournalist, in a way. So that's how I ended up with that material.

Haden Guest 18:53

With this respect that you have—and it's so evident—for the integrity of these images, there's also... what I really admire about this film is the way you allow all of the people you speak to sort of tell a bit of their stories. We get these glimpses in a little bit more of their lives. I mean, Kaufman's first wife, you could obviously make your film just dedicated to her; she's so extraordinary. But I love the way you give a little bit more space—it's not just about Kaufman, it becomes also about themselves and the family and in New Orleans, the beatnik priest and all of this… There’s this extra space that's given for this.

Billy Woodberry 19:37

I tried to do that but what happened was the first cut was really long. And people told me “Billy, these people are talking too much.” And I could listen to him talk. Fortunately I have the material, so people can consult it I hope you know, because they gave me a lot more than I was able to use because at a certain point, you need to find a workable structure that somehow carries what they had to say and what they offer. And their scholars, so I'm not doing justice because I don't give them the space and time to do that. But in terms of their contribution to this, I tried to find a way where I kept something of them. And at the same time, they helped me to construct an account of his life and what he meant, and that kind of thing. It’s their view, their research and that kind of thing. That's what I think I did.

Haden Guest 20:47

Now, in terms of the structure of the film, I think, this is something else I think is really so special, is the way in which you begin from perhaps the most iconic, you know, imagery of Kaufman, The Flower Thief, and then you pull back layer upon layer, then suddenly we go back in New Orleans, and we're back to his work as a union activist. And so I was wondering if you could speak about the structure—which is not chronological—and makes these associative jumps? And so is this reflective of your own process of discovery? Does it does it follow that path, the structure of the them, or…?

Billy Woodberry 21:26

It's partly that it's a risky thing, because maybe it's not the normal way of doing it. But at a certain point, I knew this is how people know him to the extent that they know him, right? And I hadn't found so many accounts of what happened before. As I discovered, in the end, going forward with searching, at a certain point, you want to know, who was this guy? What's his story? in a way, right? So I thought at that point, I could go back to that story. So I go, without warning to New Orleans, and then I start from the so-called beginning. And I come up to a point. And then I return to the 70s or something. Because what happens is he has a break, and in a way, we leave him after that poem: [We know some things, man, about some things / Like jazz and jail and God,] and his sort of his crash. Then that allows me to go back I thought, so that's how I kind of worked it out. It was working, working, working, trying it, convincing myself and those I was working with that it could work. And we tried it. I hope it works.

Haden Guest 23:18

Oh, it definitely works. I mean, something else that works with such a strength is the is the way in which you deal with the poetry itself, and as well if you could speak a bit about the challenges and impossibilities of creating the sort of space to let the poems be alive. I mean, you so clearly understand and this film teaches us the importance of poetry as a spoken form, the different readings that we have. But then there's also this wonderful poem about Charlie Parker, where suddenly you're making this film that's in dialogue with the poem and not literal at all, but just doing something else. And so it feels like a film within the film. But one of many different ways in which you are engaging, animating, allowing Kaufman's poetry, to breathe and to be alive. So I was wondering if you could speak a bit about...

Billy Woodberry 24:16

I hope so! When I was first editing the film, in a way, I wanted to tell maybe too many things. And again, my friend Sally Stein said to me, “He's a poet. People want to know about the poetry. They don't want to know about this.” You know, this kind of thing. Okay, so I didn't totally agree with her, but I agreed with the poetry, so then it was a matter of how to do it. And also realizing that I'm making editorial decisions because I don't give you the whole poem always. I give you sometimes a fragment of the poem. Am I being just? Am I being fair? You know, in terms of what I'm allowing you to hear or see or know, because I'm not giving you the entire thing, right? So that's part of it, and then finding, it's a long process, and then working with the editor, and then working with the editor at the finish, as important as all the work that went before was, you refine it. You realize that what you thought worked, maybe didn't exactly. So the sessions, the time, the month, month and a half or two months that we spent refining it. And also I have to say, the young man, Luís Nunez that I worked with, he learned as much of it as he could. And he proposed even more of it, because he fell in love with the poetry. And so therefore, we found things that maybe we didn't have in the first edit of it, that kind of thing. And also, because he's a cinema person. The decision we made of what could work with what... Dion Ving had made this sort of single-frame movie [?moment?] through the streets of San Francisco. And I liked it, but I didn't know a place for it. But then with that poem, and maybe a bit of extending it, it seemed perfect, you know. So you have to try and remain open, even as you're trying to finish something, you know, was partly how I found it. I got to know a lot of these readings and a lot of the ways of doing it. I was pressed to read myself by the young team that was working with me, because they thought You need to be in the film. People want to know, this kind of thing. It's their view. So they convinced me and I said, Okay, I'll try to do it. I'm there. I'm cheap. [LAUGHTER] I did it.

Haden Guest 27:40

Just one follow up. That footage of the street—that jittering footage—is so wonderful, because the street itself is so important to Kaufman's work, and so yes, I think that's fabulous.

Let's take some questions, comments from the audience if there are any. Just raise your hand if you have any questions for Billy. We'll start right here, the gentleman with the suspenders. The microphone is just coming down from the side. Actually, if you could just wait for the microphone, that would be great.

Audience 1 28:12

So, first, I want to say that it's an extraordinary film, and it has shown me many, many things I had no awareness of. And I had no one whereas Kaufman, and you've made me very much want to read him.

I want to ask you a little bit more about the choice of where to place the union and political material in there because for me, it was extraordinarily effective at putting together things that I'd never quite realized meshed with each other. Do you have some analytic process that told you that was where to do it? Mysterious to me...

Billy Woodberry 29:09

Actually, I knew it should be there. I knew it was an important part of his story, even if for some it seemed without really good reason. I knew that it was really important to him. And I know it's important, because in a way it’s a film about Kaufman, but it's also film about the mid-century in the United States and the culture, politics, the ferment, and it happens that he, as a young man, 1942, he joins the Merchant Marine, is seventeen years old, that means he's in the war. As a very young man, he's in the Atlantic, which was the most dangerous place to be. And then he joins the union in a way, you know, it's like Gorky’s book, that was his university, you know, that's where he came to adulthood was in this union. And apparently he was a meaningful person for the people in the union because they elected him a number of times as a leader of the rank and file to represent them. And he was well regarded by the leadership of the union and by the Communist Party, because they offered him to be the head of education on the waterfront. This is not a joke for a twenty-one-year-old guy. So I knew those things were important to him. I knew because of their organizational links, and because of who they were. People say, “Well, I didn't see the direct impact on his poetry of the Rosenbergs.” Right? And I don't tell everything, but when Ida tells you the trade union that hired her and that she worked with, that's the trade union that Julius Rosenberg belonged to. And they most certainly were disturbed and active and all of those things about that thing, and Kaufman later in a poem, he challenges a Pole in there to rise from his grave in Pére Lachaise and write a poem for the Rosenbergs. It's a kind of drunken thing, but wonderful. So those things, I knew they were related. And I know he was in the Wallace campaign. So then with the film, though, it was a matter of how to do that, how to make it meaningful, how to make it not so... with a hammer, you know, which is what I was doing at first, because I had still pictures. Then I found that when I had footage, it was better, because you could have the same information, but because it moved, it didn't seem as long. And also, I found more effective ways of doing it. Not always explaining everything by text. Using it sparingly, but to some effect, I thought. And that's how I worked with it. And I had to extract some things because I wanted to tell you about the Peekskill but that's already been told, right? Yeah, he was alive then, but he wasn’t at Peekskill. Some friends [were]. So I had to choose the things that related directly to share. And it's not like I'm making it up to make him a meaningful guy. It’s part of his story.

At a certain point, people became reluctant. He was not a guy who was always narrating his biography. People have very scattered and you know, very poetic things about his life as a sailor, his life as an activist, his life before... The man who made the film at the end... Heartbeat is a film by a man called Will Combs. He made a film about that North Beach scene, about 1978, ‘79. They all cooperated with him. But when I first talked to him, he said, “Nah, man, he was not a guy tied down by history.” Now, we kind of agree that yeah, he had linked to that. It's just that he didn't go around explaining it. But if you live through the McCarthy era, you didn't go around explaining a lot of things.

I just saw a wonderful book I hope to read about a woman who discovered that her uncle died in the Spanish Civil War. But the father only fed her bits of information about the uncle. And it was only when she received this trove of letters and other things that she found the story of the uncle.

So sometimes it was caution. And he genuinely was not a guy who was always sort of building himself up or whatever. So he didn't tell a lot of things, or he told you in a kind of aphoristic and poetic way that you could believe it... You'll be like the guy when he says he was in Dante's Inferno. [LAUGHS]

Haden Guest 34:55

Other Other questions? This is yes, right here.

Audience 2 35:03

Not to belabor the point, but I did find the footage and all the parts of the film having to do with [INAUDIBLE] really amazing. And part of that is because I had in my mind bits and pieces about Bob Kaufman's life, but because he was such a mythical, legendary and kind of evanescent figure, you know, you never knew what was real and what wasn't. And to see the actual documents, to learn that he was purged from the union at the time when that many Black workers were purged. And then to see that in the film and put that together with the incredible poetics. I mean, it somehow created a space for that transition into that level of poetic expression. It's not labored in the film, but I really thought that it's one of the most powerful aspects of the film.

Billy Woodberry 36:06

Oh, thank you. That gives me a chance to acknowledge something else. These scholars, they didn't only give me an interview, they gave me all that they had written about him. And we shared, they gave me the research because James Smethurst—who teaches at UMass Amherst, who I wish were here tonight—he found the issues of the pilot where Bob Kaufman… and references to Bob Kaufman, where he appeared and photographs. Maria Damon actually went to Rutgers and found the issues of the paper. And Maria Damon is the person who read the text that allowed me to find Ida. And so I need to thank them for more than their appearance. It's a reason that I have to do those things.

And I will tell you something—since you found that interesting—the way I found two films that were made by the NMU that I might have, I was hoping existed, but I didn't know they existed. Something called the Labor Video Archive put them on YouTube. (And all these years, I'm still searching, you know, periodically to see what else comes up, and I'm still finding things.) And they put these films on. And I call the guy up, you know, I saw who posted it, I called him up. And he says, “Yeah, we have those.” And I say, “Well, can I get them?” And he says, “Yeah, you send a donation, and we'll send you a DVD.” So I sent him a bit of money. They sent me the DVDs. And I said, “But how did you get them?” He said, “Oh, we pulled them out of the dumpster. And we transferred as many as we can—as we acquire the means—we transfer them to DVD or to video. And we you know, we try to post some online to get people who are interested, and we try to conserve them.” But he said, “Yeah, we found all of them in the dumpster.” So that's how I found them. And they're wonderful.

Haden Guest 38:41

Question right there.

Audience 3 38:50

Just to pick up again on the previous two comments, one thing when I did I take away from watching the film, I'm wondering if you put in the film. And that was this, you know, the fact that he carried these two major post war themes being involved with the anti-communist hysteria and the blacklist on the one hand, and beat sensibility, on the other hand, seems like more than just the juxtaposition it seems almost like if he hadn't been marginalized, by the anti-communism, would he have become a beat poet? And what, to some degree, wasn't the cultural rejection of the conformity of the postwar culture in some way, a creation of J. Edgar Hoover—insofar as it was a reaction to that truncated sensibility? So I guess I'm wondering, do you see, Kaufman as just sort of sequentially going through these phases or partially is poetry being created as a response to his political experience?

Billy Woodberry 40:01

Two things I can share. One is his brother, his older brother, who's the guy who brought him into the Merchant Marine because he himself was a sailor. And he's his older brother, four or five years older. And so when Kaufman is a young man, and he needs a job, he follows his brother George, into the Merchant Marines. And George feels that in a way, Kaufman was continuing his politics, and his desire for change and for justice, through poetry. And George thinks, maybe it's a better way, because it's more abstract. They don't come at you the same way as when you are a militant, and you are working in the Wallace campaign in South Texas, you know. Poetry, they have to kind of figure it out.

There's another part of it. It comes from his early life, because as his sisters say, his mother was very pleased with him, because he loved reading. And he had a great memory. And at first, they started out doing limericks and games, you know, word games and this kind of thing. But he learned a great deal of literature and poetry and a love for that when he was very young, because she encouraged them to read. When she had not many other things, she bought books. And then they shared the books. And you pass it to the next one. And it was something that was valued, because she had been a schoolteacher before she had all these children and had to leave teaching. So she decided I'll teach them. And she did.

So he had this already, he was a reader. And you know, the history of sailors is they are readers and agitators and carriers of ideas. Right? So they have that since a long time. And he sort of fell in and enjoyed a great deal of that culture. I asked his first wife if he had expressed desire to write or anything like that. Her thought is, he discovered a capacity in himself that he didn't know, or believe or understand that he really had later. He wrote things but not like that.

And he well, he's kind of special maybe and kind of gifted. At least some scholars think so because he seems really advanced for a guy who was not at university or reading those things for that reason. So he's kind of gifted in that way. And we have to remember—and this is one thing that the poet David Henderson—who made a long radio documentary (two hours, you can get it from Pacifica Radio about him about Bob Kaufman, called Bob Kaufman, Poet) and the beats themselves they speak about this: Kaufman was a kind of link because he was a hipster, even though he was a left guy and a union guy and that if you see him in that photo with the other men, he has the same high-drape pants as Charlie Parker. So he was a kind of hipster and a bebopper while being a left-wing guy, and as Ida says, “Our office was in a village. Our life was in the village.” So he was always a kind of bohemian guy. He was always like that. And that was permitted—believe it or not—in the CPUSA. As they say about the CPUSA and Harlem, “The party was a party.”

[LAUGHTER]

Haden Guest 44:21

Other other questions?

I mean, this question of the political dimensions of this poetry... This idea of the vow of silence being somehow partly inspired by Kennedy's assassination. I mean, I love the way you just have the Zapruder footage just very faintly in there. So I mean, what are different theories on that? Is the dominant belief that that was in fact true, or… ?

Billy Woodberry 45:02

They argue about that. They know better, and they repeat it anyway because in some ways he was willful. His widow told me that, in fact, he did that. But maybe she's part of the people who helped to create the legend. The beatnik Preece completely disavows it, and says he kind of burnt himself out on things he was taking, that kind of thing. But it persists that this happened.

I have to say this, okay. There's a recording by a young composer, and it's called Follow Poet—you can probably find it online—and the first section of the composition, as a matter of fact, is not accompanied by music. I'll tell you two things. Raymond, in the radio documentary, talks about the fact that Kennedy passed through San Francisco and Kaufman met him and thought a lot of him. But I'm going to tell you another thing I just discovered, is in this recording, there's a talk that President Kennedy gave at one of the New England schools, and it's about poetry, and what poetry does for humanity. And I don't know that Kaufman knew that—even though Kennedy made the speech at a certain point. But if you read that speech that Kennedy made, and you were a poet, you might like him, too. Because he makes a lot of sense, right Now, I don't know that he knew that. But I just heard this record, I just bought the record.

And the other thing is, I don't want to go on or be too precious about this. But I was a boy in Dallas in 1963 when Kennedy was killed, and I was telling my wife that I still remember that pink Chanel suit that she wouldn't remove. Even when she went on the plane to go back to Washington and Johnson is sworn in, she's still wearing that suit. So for me, that image was sort of about that, and it was about his love for Billie Holiday. And to me, that was solitude. And I'm thinking he's a man who’s sensitive enough that this would, you know, wrench him. So that's why I put that together. Me and a young man that was editing with me, Patrick Scott, we sort of worked that out together. Patrick sort of found those things and we worked that out.

Haden Guest 48:11

Thank you, Billy. It's poetry. And Bob Kaufman did not sadly ever read at Harvard. But thanks to your film, and thanks to screening tonight. I feel like maybe he did.

Billy Woodberry

He’s here.

Haden Guest

Please join me in thanking Billy Woodberry!

[APPLAUSE]

© Harvard Film Archive

Related film series

Explore more conversations

Ross McElwee & Adrian McElwee

Christa Lang Fuller

Paolo Gioli

Kelly Reichardt