Robert Flaherty's Oidhche Sheanchais panel discussion. Speakers include: Catherine McKenna, Natasha Sumner, Haden Guest and Liz Coffey.

Transcript

John Quackenbush 0:00

May 20, 2015. The Harvard Film Archive hosted a panel titled, “Spotlight on Collections: Robert Flaherty's Oidhche Sheanchais.” The participants included Catherine McKenna, Chair of the Department of Celtic Languages and Literatures; Natasha Sumner, incoming Assistant Professor in the Department of Celtic Languages and Literatures; Haden Guest, Director of the Harvard Film Archive, and Elizabeth Coffey, film conservator at the Harvard Film Archive.

Brenda Bernier 0:34

Good afternoon, everyone. And welcome to the Harvard Film Archive. My name is Brenda Bernier. I am the head of the Weissman Preservation Center in Harvard Library. We're here to celebrate the rediscovery, translation, preservation and research potential of the first Irish-language talkie, Oidhche Sheanchais, pardon my mispronunciation, or, A Night of Storytelling. It's a short film made by Robert Flaherty in 1935. And it's a special film for many reasons, not the least of which is its appeal to many different kinds of scholarship. This event is part of Harvard Library Preservation Services’ “Spotlight on Collections” series, in which we invite the Harvard community to peek under the hood, as it were, of some of the Harvard Library's extraordinary research collections. We feature presentations by faculty, scholars, librarians, conservators, and other preservation staff, highlighting the collaborative efforts and new technologies involved in preserving and making these collections accessible for teaching and learning, and how these efforts impact the research value of the collections. Today, you're in the company of an interdisciplinary audience, made up of students and faculty, conservators and librarians, storytellers, filmmakers, and historians in many different areas of study. And the presentations and screening of this film will last about an hour. And then we hope you'll stay for some light refreshments and conversation with these diverse colleagues. I'd like to thank our speakers for your contributions towards bringing this film to light: Harvard Film Archive Director and Visual and Environmental Studies lecturer Haden Guest; film conservator Liz Coffey; Celtic Department Ph.D. graduate and rising Assistant Professor Natasha Sumner; and the Chair of the Celtic Department, Professor Catherine McKenna. Hayden and Liz also worked on planning the event, along with Priscilla Anderson, Leslie Morris, Brittany Gravely, Mark Johnson, Jeremy Rossen, and John Quackenbush. Special thanks to our projectionist, Clayton Mattos. We're grateful to them for putting this all together, and to the HFA and the Carpenter Center for allowing us to host this event in this wonderful space. And while I have your attention, I want to alert you to an interdisciplinary exhibit in Pusey Library lobby of 19th-century Harvard class albums and the early history of photography, which has been extended until June 29. So if you haven't seen the exhibit, feel free to pick up a card that looks like this, and it will be in the, towards the refreshments. And there's some more information in there.

So now I'd like to introduce our first speaker and our master of ceremonies. A film historian, curator, and archivist, Haden Guest is Director of the Harvard Film Archive, overseeing HFA’s cinematheque, preservation program, research initiatives, and its renowned collections. Since receiving his Ph.D. in 2005 from the University of California Los Angeles, Guest has focused on research on postwar American experimental film, and contemporary Latin American and Portuguese cinema. He is currently at work on an essay on the films of Robert Beavers, and a book tracing the histories of radical narrative filmmaking in post-Salazar Portuguese cinema. Recently, he has curated film programs at last year's Biennale, sorry, and in Lisbon, where he was awarded a Medal of Cultural Merit by the Portuguese Ministry of Culture. Guest was also a co-producer of Soon-Mi Yoo’s celebrated documentary, Songs from the North, winner of the Golden Leopard for Best First Film at the 2014 Locarno Film Festival. Please help me welcome Haden Guest.

[APPLAUSE]

Haden Guest 4:42

Thank you all for being here this afternoon. I want to thank Brenda and Priscilla for making this event possible. I think it's really wonderful that we can come together as a community and learn about the ways in which we discover and make accessible some of the treasures that at times are hidden right in front of us, which was very much the case with A Night of Storytelling.

This is a really fascinating and pivotal film in the career of its maker, Robert Flaherty. And for those of you who aren't familiar with his work, Flaherty is known today really as the father of documentary cinema. It was, in fact, in a review of one of Flaherty's films, called Moana, that the term “documentary” was coined by a British filmmaker, John Grierson. And Flaherty, from his very first feature film, Nanook of the North, in 1922, he invented a form that, I think, a form of, an approach to cinema that is, at its core, I could just say, I want to say problematic, in a really good way. Problematic in the sense that it instantly raises questions about the relationship of camera to subject, of artist to reality. A question that I think is really, is one of, like a set of questions that I think is one of Flaherty's great, greatest legacies. And this is to say, in Flaherty’s films, where he often depicted, told stories of Man, capital M, locked into a type of eternal struggle with Nature, capital N, in telling these stories, in crafting these really extraordinarily poetic and beautiful films. He took great liberties, as many have painstakingly documented and researched, that is to say, they were often reenactments. He would essentially cast real-life subjects as kinds of actors. So in a film that he made in the Aran Islands, he created a family that, in essence, didn't exist. He cast three Aran Islanders as a sort of nuclear family. The result is, of course, one of the great films about the Aran Islands, a film, Man of Aran, that is celebrated as one of the highlights of Flaherty's career. Little known, in fact, almost entirely forgotten, is a film that Flaherty made at the same time, basically, around the same time as Man of Aran, just shortly afterwards, with the cast of that film. This is the film, A Night of Storytelling. And when I say this is a pivotal film, I think that it, we'll be watching it in just a few minutes, it's a film that crystallizes a kind of, a type of imagery, a type of idea, that was absolutely central to Flaherty's cinema -- storytelling. And Flaherty himself was a master storyteller. But I think what this film reveals is this great interest in the folkloric, in the mythological imagination. And this isn't just a passing interest. But this film also shows the kind of rigor that went into Flaherty's cinema, into the type of research investigation that he would do. Here he was, of course, working with a famed folklorist, James Hamilton Delargy, who was a consultant on this film. And you'll see, this film stages a storytelling session gathered around a hearth fire. And I think the film is so poignant for its really delicate artificiality, the ways in which this soundstage set the limits, defined the sort of single shot, the camera almost doesn't move. And at the same time, out of this artificiality, out of this theatricality, arises something, really heartfelt authenticity. This is a recorded document, the first motion picture made in the Irish language, but it's also a vivid document, and a sort of monument to a great storyteller and a great tradition. “The Tale of the Knife Against the Wave,” which is told, is an age-old Irish tale. And it's one told often many, many different variations. It is itself another variation of “man against nature” that would be Flaherty's dominant theme. So this film, I think, really helps us, I think, understand a different aspect of Flaherty's cinema, of his cinematic imagination. And so it's a real thrill to be able to now add this to the filmographies, and to allow this film to be written about, and to be really appreciated as it should be. Others today will be speaking about, our other speakers will be speaking about the importance of this film to the Irish language, to, really, Irish history. And so, I really just wanted to focus on speaking about Flaherty himself. So we're going to take a look now at the print, this film runs 12 minutes long. And so this is the first, this is Flaherty’s first work in direct sound. Man of Aran, the sound was recorded afterwards, then added to the film. But this, he was actually recording it on set. And this was, we should remember, this was relatively new technology. While sound had been introduced into cinema in the late 20s, it was slow coming to different parts of the world. And that was true in Ireland. And the film still, I think, sort of crackles with the magic and the sort of excitement of this new technology. And so we should remember that the very act of making, the very, the real thrill of actually seeing moving images speak, that excitement, I think, is palpable in this film. So now we're going to take a look at the 35 millimeter preservation that was done here at the Harvard Film Archive, overseen by Liz Coffey, who’s going to speak afterwards. And so let's take a look now at A Night of Storytelling by Robert Flaherty.

[PAUSE]

[APPLAUSE]

Haden Guest

So, I had the great thrill and pleasure of being there to open this metal box that was sent over to the Harvard Film Archive by Houghton, with my colleague, Liz Coffey, who's going to speak in just a minute, and to discover within it a wheel of nitrate film that had not been touched, since it had traveled across the ocean here. And it was clear to us that it hadn't been projected either. So this was a really pristine, absolutely gorgeous print that had been carefully safeguarded by our friends at Houghton for many, many years. And we realized that we had to make this film accessible, and we needed to preserve it. And for us at the Harvard Film Archive, it’s very important, in thinking about film preservation, one of the real tenets is being true to the original. In this case, we have a film, and we still have the technology available to do photochemical film-to-film restoration. So this is why we have now a 35 millimeter print. This film was first exhibited theatrically and I just want to emphasize that, you know, here, we don't just preserve film, we also preserve the film experience. That is, the experience of seeing a film in its true dimensions on the big screen with others, in the company of others. That's very important, especially when we're thinking about a film like this, that is so much about language and community. At the same time, though, we also, this film will also be available on Blu-ray and on other formats. So we really wanted to have these two, to have the film available on many different platforms.

In thinking about the preservation of this film, we also decided that we wanted to be true to the original in the sense of really be true to this original print that we found, that was discovered here. And that is to say, we weren't going to do any digital cleanup, remove any of the, you know, the little, you can see some sort of photochemical stains, and, and crackle here and there. And so we didn't, there’s a tendency now, with digital technologies, to actually clean up, and quote unquote “correct” photochemical mistakes, to more finely tune fringing of colors and things like this. And no, we wanted to really keep alive and keep true to the spirit of the original here. Another decision too, this idea of the credits, I think, for preservation and restoration work. Oftentimes, I feel like too many, sort of, oh, I don't know, give way to, I think, a terrible temptation to sort of announce, you know, to really put their credits first. To announce that this is a preservation, you know, right away, and then to go through the detailed history of that preservation right from the beginning. And no, instead, we wanted the film to begin as it was meant to begin, here with the bold declaration for the Free Irish State. And then to put our credits more modestly at the end.

Now to speak about the preservation work is my good colleague, Liz Coffey, who has worked with motion picture film in one way or another since 1996. She's a graduate of the Jeffrey Selznick School of Film Preservation, which is at the George Eastman House in Rochester, New York. And she's been the film conservator at Harvard since 2006. Oh, she has toured Ireland twice by bicycle. Please join me in welcoming Liz Coffey!

[APPLAUSE]

Liz Coffey 16:01

Thank you, Haden. That’s okay. I swear I don't have a real PowerPoint. I just have some pictures for you.

Liz Coffey 16:23

So as Haden mentioned, the film was originally brought over to the Harvard Film Archive from Houghton Library. It was walked across the Yard in a metal crate. I'm afraid I don't have a picture of that one. But we suspected it was nitrate, because of the year that it was from, which is 1935. And nitrate was the standard film base for motion picture, for 35 millimeter, from the dawn of cinema up until 1952. It was found to be extremely flammable, there was a lot of fires around it in movie theaters. Sometimes, there would be fires associated with couriers who were moving films around. A lot of early cinema was lost as a result of the decomposition and also because of fires. And this particular film was believed to have been lost, every copy of it was believed to have been lost, in a fire in Ireland. I'm actually not sure if it was in Ireland or England, but it was believed to be lost in a fire in 1943. So this had been something that would have been long sought after, as both a Flaherty film, and the first film in Gaelic. And as we were watching it, I realized that there was actually a few moments where there's some dubbing of the sound. I hadn't really thought it through until just now. But there's a couple moments where Maggie says something in reaction to the storyteller. And that's actually dubbed, you don't see her lips move. So that's kind of funny. I didn't think I could watch this film forty times, and still see something different.

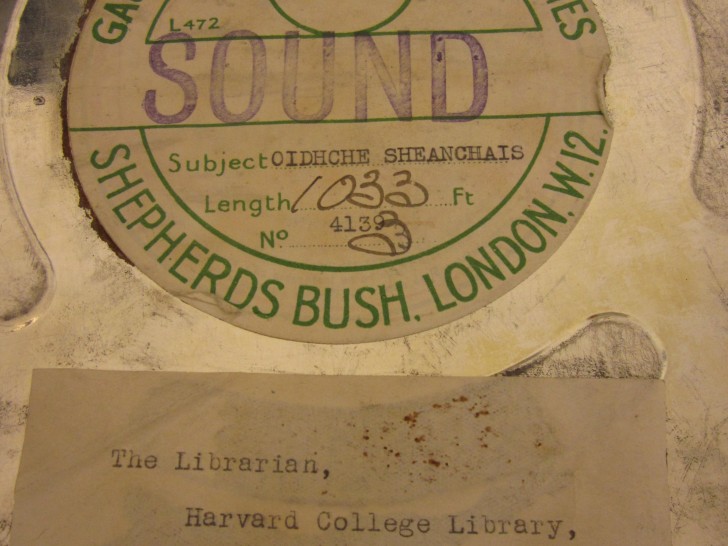

So this is the film can that it arrived in, that's the original label from the lab. It tells us that it's a sound print, that it's 1033 feet, and it's addressed to the Library Inn at Harvard Library. This arrived in a box that had all the shipping labels on it also. So we expected, we knew it was nitrate and we were concerned that it had been sitting at Harvard for quite some time, in a vault that was not as cold as we would like nitrate film to be stored in. I'm going to show you a little video. So things that are made of nitrocellulose today include ping pong balls. This is the same sort of stuff that the film is made out of. You can see that it's quite volatile. Nitrocellulose is no longer used for motion picture. This is, so this is celluloid. These are all kind of the same plastic. Motion picture is now made out of, motion picture film is now made of polyester, mostly. Triacetate as well, neither of which are dangerous. And the other thing about nitrate is when it decomposes, it starts to look really gnarly. And this is not the film that we found when we opened the can, thank goodness. But as you can see, the can lid on the right is covered in rust, which is something that happens to the metal that comes in contact with the decomposing nitrate. And that's a roll of 35 millimeter. It's kind of bubbling, there's a lot of brown powder. And then what happens to the image for decomposing nitrate is it starts to fade, and you'll see kind of the middle is pretty dark, you can see a nice image of a person and a fountain. And then the edges, the ends, are faded. And these are places where it's broken because the film has also become very brittle. So the emulsion disappears as it's decomposing. So these are things that we were afraid of when the film arrived, and we were extremely happy to open the can and see this, which is, like, looks brand new. And there's this little note here on the inside of the lid that says, “This film has been projected and found in good condition.” So, and it was still in good condition when we found it, as well. This is something that maybe no one else has seen. It's the lab’s, the film lab writes on the leader of the film before they put it through the machinery, and this is what they had originally written on there. I guess they couldn't spell the Gaelic, so they wrote “Gaelic storyteller.” So this particular nitrate film did not have a nitrate edge code on it. Generally speaking, 35 millimeter nitrate motion picture film says “nitrate” on it very clearly. This was extremely common. And it also will usually have some hatch markings that also identify it as nitrate. And this didn't have any of that. But nitrate has a really specific odor. So this is a case where conservation involves huffing whatever you're investigating. So it smells very sweet, kind of like a, sort of like a sweet candy or something. Once it starts decomposing, it starts to smell sweet in a really gross way. It smells to me like rotting bananas. Other people think it smells like bad socks. But so the smell of the film was the first thing that tipped us off to it actually being nitrate, even though that's definitely what we were expecting. And then we did, I did cut a little tiny piece of the clear leader off to do a definitive test, which was a burn test that looked much like that ping pong ball video. So we don't have a motion picture lab at Harvard, we needed to send this out to a vendor. So we got some quotes from a few different people in the field that are still doing photochemical work. And we also decided that since this was a print and not a negative, that we wanted to do a digital intermediate. And that meant that we didn't lose a layer of, we didn't lose a generation. So we went from the print to a digital copy of it that we were able to make our masters from. So we were able to make a new negative and new prints from that. And yeah, so that, the print that we just watched looks very much like, if we had been able to watch the original nitrate, which we were not able to do, then it would have looked very much like that. And as Haden said we didn't want to change it from what it was in 1935. So that's why you're hearing some crackle on the soundtrack. That's what it sounded like then. So the film turned out to be in really great shape. It had just a couple of splices and those were in the leader, they were not in the picture. It wasn't on a core, but that didn't prove a problem to us. And it didn't have any edge damage or anything that had been found in projection. A lot of that white dust you’re seeing was probably introduced into the print when it was made. So that was like a dirty negative that had been printed. So I guess a lot of that white dust would have been seen every time this film had been shown.

Liz Coffey 23:20

This is what that first shot looks like. As you can see, this is the soundtrack, these white lines. So when we looked at the print, we didn't know if it was in Gaelic. We assumed it was, since all the text was in Gaelic, but we didn't know for sure what we were going to hear when we had this copied. This is a little bit shrunken, it's about one percent shrunken. Also it’s nitrate, we don't run nitrate in our projectors at Harvard. It's the viewing of nitrate has a lot of extremely important fire safety rules associated with it, as you might imagine. And there's nobody in Boston that can legally project it. We don't also run any of our master material through machinery. So we wouldn't want to be showing it in our Steenbeck, or anything like that, unless we were able to copy it at the same time. So we basically sent this, we knew what it looked like from looking at it, you know, with the magnifying glass, but we didn't know what we were, exactly what we're going to get until it came back from the lab. So we sent it to the lab. They copied, they digitized it, 4K scan, and then they sent us a pretty low-res copy of it that we were able to watch on the computer and verify that it was in Gaelic. So that was nice. There was no subtitles. We'll be talking about the subtitling later. But so when I first watched it, it sounded fantastic, but I had no idea what they were talking about.

Liz Coffey 24:54

There was a lot of little things involved in the communication with the lab, and the preservation, and the communication among us, because there was, you know, several different entities at Harvard working on this project. There's a lot of interesting things about the translation that I hadn't really expected to be as controversial, or even, not really controversial, but that there would even be questions about how this would be translated seemed, was surprising. So that was a lot of fun to work on that. I’m swinging this slide, because this right here isn't an edit that was in the original. So if you see those two white lines, that's a cement splice between two shots. The work was done at FotoKem in Los Angeles. And then they sent the prints, or they walked the prints over a couple blocks away to another vendor who did the subtitling. So the print that you saw just now was 35 millimeter polyester. The subtitles are laser-etched into it by machinery. They were able to turn that around really quickly for us, which was very nice. The digital, so we made several prints that have English subtitles. We have a couple of prints that have no subtitles, and the digital versions, the Blu-ray and the DCP, will have your choice of no subtitles, English subtitles, or Gaelic subtitles. So if you're learning Gaelic, and you want to have a visual interpretation of what they're saying, we can look at that. The other thing I wanted to mention was the titling that we made. So you saw that first, like, opening, scrolling credit that describes what is going to happen in the film. And then we have our translation of that. And the reason that that wasn't subtitled was the subtitlers said that it would just look too weird to have scrolling text, and then also static translation at the bottom. So that's why that is a different, that's the only thing that's really different about the film, is that that English text has been put in the middle or added to it. So what we have produced at the lab was new 35 millimeter film picture negative, track negative, the new digital 4K scan, which is our master digital product. And then we'll also have Blu-rays and DCP. The Blu-rays will be available at several different libraries. And I believe some of them will also be going to Ireland, as well as a film print will be going to Ireland. I think that is all I have to tell you for now. So that's “The End,” in Irish. And I'll take your questions afterwards.

[APPLAUSE]

Haden Guest 27:46

Well, thank you, Liz. So, one of the great challenges, and I think pleasures, and one of the most fascinating dimensions of this project was indeed the translation. And we were so fortunate that, to be able to work with the Celtic Department, whose foresight made possible this whole preservation, and the rescue of, and rediscovery of this real gem. And so we were able to work with Natasha Sumner, who will receive her Ph.D. in Celtic Languages and Literatures this month, and will be joining the department as an assistant professor in the fall. Her research focuses on the Fenian narrative corpus, comprising stories and songs from the hero Finn McCool, Fionn Mac Cumhaill, and his roving warrior band. She also publishes more widely on aspects of post-medieval Irish and Scottish Gaelic literature and folklore. So she transcribed and translated the subtitle text for this film, and also coauthored an article about the rediscovery, restoration of the film with Catherine McKenna, who will be speaking shortly afterwards. Just to say that, you know, this translation involved such a sort of careful level of nuance, and kind of poetry as well. And so I really want to commend Natasha for that work and for her patience, because it also involved an endless stream of back and forth: “Is this really what it should say? Is that how it should say?” Because don't forget, when we're talking about subtitles, is what's different. This isn't an exact translation, in the sense you also have to think in the duration of these subtitles, and how that they can only be on screen a certain amount of time. So there’s, it poses, and you can only have a certain number of characters. So it's a unique mode of translation that's, I think, very different from any other form. So please join me in welcoming Natasha Sumner.

[APPLAUSE]

Natasha Sumner 30:08

Okay, like Haden said, I did the subtitles for the film. I was asked to work on the film and do these subtitles probably a little bit over a year ago. And at the time, I happened to be away on an extended research trip in Scotland, where I was struggling to finish up all of my work in the folklore archives there before I had to leave. And if this had been any other project, I very well might have said, nope, sorry, don't have time. But this wasn't just any film, of course. This was Oidhche Sheanchais, the long-lost Irish folklore film that people had been searching for, for decades. So obviously, there was no way I could say no to this.

So the very first task that I had, was to transcribe the verbal soundtrack. And the soundtrack, as you've seen, is about ten minutes long. We've got the opening song. We've got a bit of dialogue. And then there's the story, and that takes up most of the film. So, and then, couple audience interjections here and there. But, mostly just the story. And I was helped an awful lot with that part of the project, by the fact that the text of that story had already been published. It had been published, in fact, quite some time ago, right around the release of the film, in a pamphlet that was released by the Department of Education in Ireland. Only in Irish, so. You can't read it from here, but I promise you, this is in Irish, it's in Irish script. So if you want to come and have a look at this, at some point later, after we've all finished talking, go right ahead. Because it's quite interesting to see what people might have had available to try and understand this film, because, of course, not everyone in Ireland was fluent in Irish, although a lot of people were learning. And the point of publishing this periodical was ostensibly so that students, schoolchildren who would be taking Irish lessons, could go and attend the film, and hopefully try and understand what it said.

So, I had that to help me out for that bit. And it was quite useful. It's fairly accurate, it's only missing a couple of interjections. The really difficult part, for me, was transcribing the song and the dialogue that precedes the folktale, because these had not been published at all. The song itself is performed in sean-nós, or traditional style, in which pronunciation and emphasis can be a little bit distorted in comparison to regular speech patterns. So that made it a little bit more difficult. And in addition, if there's anyone here with Irish, and I'm sure there are a few, you will notice that it is rather dialectal. Now being a learner, I took full advantage of all of my friends and colleagues from the region who could help me out, especially anyone who was a traditional singer. Now once one of my friends, one of my song friends, was able to identify the song, because I was not actually familiar with it, things really fell into place quite quickly. So the only bits that neither I nor anyone that I consulted with could get, throughout the whole film, were really just a couple of interjections that were too faint to comprehend.

Now, once the transcription was complete, I moved on to the translation. And here, I had to consider the film's audience, and of course, as Haden said, the fact that this film had to be subtitled, the subtitles had to be these short little bits that could appear on screen. And, you know, also taking into consideration the fact that this might be viewed over a period of time. So basically, the most important thing was clarity. Now for most Irish language films, I could presume a reasonable level of cultural knowledge. But for a Flaherty film, I had to be extra, extra careful to get that level of clarity, simply because not everybody was a local Aran Islander [CHUCKLES], who was, or even a local Irish person, who might possibly be viewing this film. So I'll give an example that'll show you what I mean there, in just a minute. The other issue is that not every concept can be replicated in its entirety in a new linguistic context. So a translator can approximate, but things like metaphor and double meaning often get lost in translation. So a good example of all of these issues is the phrase pice agus splanc. I'm not sure if you were listening carefully enough while trying to read the subtitles. But this phrase does come up multiple times in the film. And the literal translation, the literal translation, first, of the word splanc is “ember.” And a local would have no problem understanding that what is meant by both the English word “ember,” and the Irish word splanc is a lit sod of turf or peat, which is the usual source of fuel in the region. I avoided the word “ember,’ in consideration of a wider audience for whom that word could have very different meanings. It could refer to coal or wood. But in the cultural context, it was important that we could see that it was a lit, or we could picture that it was a lit sod of turf, because a lit sod of turf, in particular, is significant. And I wanted to be sure that the physical object, at least, was correctly interpreted, even if I couldn't communicate all of the greater cultural significance. In traditional Irish culture, a lit sod of turf was one of the items seen as having protective properties, so for instance, it played a part in the ritual to ensure a good potato harvest. You would take a lit sod of turf from the St. John's fire, and you would plant it in the potato field. And that would make sure that you got a good harvest that year. It could also be used as in the folktale in the film, as a protection against otherworldly malice. Now the other half of this phrase “pice agus splanc,” pice, I've translated as “pitchfork.” And it also had these protective properties, because it's made of iron. So we've got, combined in this phrase here, the power of turf fire embers and iron as protective against otherworldly forces. So with pice, there's also an additional metaphorical meaning that resisted translation that I'd like to tell you about. While the literal sense of the phrase pice agus splanc, “pitchfork and ember,” or turf, sod of turf, is quite clear from the context, there's also a heroic connotation as well, because pice also means “pike.” In the tale, we've got a poor Connemara boy, and he's throwing this pice agus splanc against this fairy queen who’s taken the form of a great destructive wave. We've got the pitchfork here becoming like a weapon of battle in a life-or-death encounter with an otherworldly foe. And that’s sort of a double meaning that really comes across in the Irish, but unfortunately, not so much in translation. So that should give you an idea, at least, of some of the issues that I encountered in doing the translation, and some of the things that I tried to take into account and to do the best that I could. Now after translating the text, basically, all that was left was to condense the text, both Irish and English, because we've got Irish subtitles and English subtitles, and you've seen English here, into the short little subtitle text. And this, of course, I did in conjunction with the Film Archive. And this really provided a nice learning experience for me, because I had known nothing about any of this. When I got the request, I envisioned, Oh, yes, I'll provide a quick little translation, and this will be simple and easy. And of course, there’s more to it, because there was always more to it. But throughout the whole process, all in all, I've really enjoyed being a part of restoring and subtitling this important little film, and I hope that you've enjoyed the end result. Thank you.

[APPLAUSE]

Haden Guest 40:12

Thank you so much, Natasha. And as I said, we worked very closely with the Department of Celtic Languages and Literatures. And we worked especially close with that department’s Margaret Brooks Robinson Professor, Catherine McKenna, who has taught at Harvard since 2005. Professor McKenna's research focuses on the narrative prose and bardic poetry of medieval Wales, particularly the literature of the 12th and 13th centuries, and on medieval saints, cults and hagiography, particularly that of St. Bridget. She teaches courses in medieval Welsh, the narrative traditions of medieval Wales, and the literature of medieval Celtic Christianity. Prior to coming to Harvard, she spent 15 years as director of an undergraduate and graduate program in Irish Studies in New York. Please join me in welcoming Catherine McKenna.

[APPLAUSE]

Catherine McKenna 41:14

Thanks very much, Haden. So I want to talk a little bit about how Harvard came to have this film, and how we found it, and what we're going to be able to do with it, now that we have it. As you've seen, and as you've heard from Haden's introduction, the film was commissioned by the Irish government, or the government of what was then the Irish Free State, specifically by the Department of Education. But as near as we can tell that, the fact that it was commissioned by the government was, from the outset, something that had been inspired and promoted by James Delargy, Séamus Ó Duilearga, you see his name on the, on the print, you've heard his name. And this was, he was a tremendously important collector of folklore in the first half, particularly the second quarter of the 20th century. He’d founded the Folklore of Ireland society in 1927. By 1930, he had sort of transformed that into a more, a larger, more substantial organization for the collection and preservation of oral traditions, the Irish Folklore Institute. And even as this film was being made, he was working with the Irish government to create a government arm, a government agency that would be involved in collecting and preserving oral tradition. And that was the Irish Folklore Commission, which came into being in 1935. So Delargy was really present at both, was at the birth of the enterprise of collecting oral tradition in Ireland, and he was also very much at its center. We're going to come back to that in a minute. But just to focus on him, in the 1930s, at the moment. He worked very closely with Flaherty on this film. There have been various things said over the years about the kind of relationship Flaherty actually had to the film, and whether he did want to do it, or didn't want to didn't want to do it, or cared about this storytelling tradition. But in the course of this preservation enterprise, research that's been done by Celtic Department alumna and associate Barbara Hillers, who's now a Lecturer in Irish Folklore at University College Dublin, research of Barbara's in the National Folklore Archive, into the correspondence preserved there between Flaherty and the folklorist James Delargy, has shown definitively that both of them were very much involved in this film. Both of them very much cared about producing this record of an actual or a traditional, well, what was like an actual traditional storytelling event. And they were both very much involved in finding the right storyteller to perform in this film. As Haden told us at the beginning, Flaherty is known for having chosen people, non-professional actors, but people in the societies that he wished to film, but then, in a sense, casting them as families, say. But this storyteller, Seáinín Tom, Seáinín Tom Ó Dioráin, was actually a traditional storyteller. A professional, if you will, I mean, known to be a storyteller.

45:27

And he was an Aran Island storyteller, so he fit in with the Aran Island background of that. So Flaherty and Delargy had a close working relationship. Now Delargy also had a close working relationship and a good friendship with Fred Norris Robinson, a Harvard professor. Robinson first got to know Douglas Hyde. Douglas Hyde was another enthusiast of Irish folklore and of Irish language. He was the founder of the Gaelic League, Conradh na Gaeilge, in Ireland. He was, in fact, elected the first President of the Irish Republic, and served in that capacity from 1938 to 1945. And he was a teacher and mentor of James Delargy. So, Fred Norris Robinson’s friendship with Hyde then led into a friendship with Delargy. Now Robinson was a Harvard College graduate, who did a Ph.D. in English at Harvard. And then he went away for a year to study Old Irish in Freiburg, with the great Irish philologist Rudolf von Thurneysen. He came back to Harvard in 1896, to take up a faculty position in the English Department, where he was the primary medievalist. Fritz Robinson edited the standard edition of Chaucer that stood for many, many, many decades as the edition of Chaucer. But he also, once he came back to Harvard from Freiburg, he began teaching courses in Irish. So we regard him as the, he is for us, the founder of Celtic Studies at Harvard. Not only because he taught those courses, but because he also, kind of under the table, as it were, was funding, from the time that he retired in 1939, he was funding one of the professorships that made the foundation in the 1940s of the Department of Celtic Languages and Literatures possible. And then when he died in 1966, that connection of him with the professorship became formal, and the professorship was established with that name, the Margaret Brooks Robinson Professor of Celtic Studies. So, I feel, occupying that professorship, I feel a real attachment to this man, who has done so much for Celtic Studies at Harvard.

So James Delargy, the folklorist, told his pal, Fritz Robinson of Harvard, he had been telling him that this film was being made. And then he wrote to him, and I have to say that another bit of testimony to the kind of wonderful treasures that we have at Harvard are these, the correspondence between Robinson and Delargy that are preserved now in the curatorial files of this film, so that I was able to reconstruct pretty exactly what happened. Delargy wrote to Robinson and said, our little film has turned out very, very nicely. And by the way, if you wanted to have a copy for Harvard, you could order one from the Department of Education for the sum of 20 pounds. So, and this fit in with things that Robinson had been doing. He'd acquired lots of other materials for the Harvard libraries. His own collection is the basis of the collection in the Fred Norris Robinson Celtic Seminar Library, located in Widener K on the third floor.

49:35

He also acquired various Irish manuscripts, including manuscripts of folktales written by Douglas Hyde, other treasures that we have. And so he ordered this film. It arrived here in 1935, in that metal can that we got to see. That was very thrilling for me. And then, though cataloged in the card catalog, hadn't made it into HOLLIS until people were doing some work in 2012 on these odd bits of things that were in HOLLIS. And that was when Barbara Hillers, who I've mentioned before as one of our own alumnae and associates, she was looking at HOLLIS one day, looking at the Irish manuscripts. And suddenly, where there had been 36 Irish manuscripts, suddenly there are 37 Irish manuscripts. And Irish manuscript 37 is listed as “a film in a locked box, Oidhche Sheanchais.” Now several other people had seen this in HOLLIS by now, and had contacted Houghton Library, had contacted Leslie Morris. But Barbara was the first person inside who said, wait a minute, we've got something important here! So um, that sort of spurred on this frantic little enterprise of gathering funds and getting the restoration done. What we see happening, going forward, is with its subtitles, and as you've heard from Natasha and from Liz, with, in varying formats, subtitles available in English, or in the Irish language, or without subtitles. The film will not only be valuable to film students, particularly students of Flaherty, but certainly to students in the Folklore and Mythology program and every sort of department that participates in their work. So, like the basic Gen Ed course in folklore, the Introduction to Folklore and Mythology, could make use of this film. Certainly, for us in the Celtic Department, it will be invaluable in a course that we offer on the Gaelic world, courses that we offer in Irish folklore, and, of course, courses in the Irish language, which is where those Irish subtitles are going to be particularly valuable, because this dialectal Irish, recorded in 1934, not the easiest thing for a learner to pick up on. But some of you probably know that sometimes when you can see what it is you're hearing, you begin to put the two together, and it helps in language learning. So this kind of traditional storytelling really lasted in Ireland. It went on in Ireland well into the 20th century. And, I mean, Ireland was very forward-thinking. And much of this we owe to the work of James Delargy in getting down to the business of collecting its oral traditions before it was too late. They began collecting folklore with the most basic technology. Wax cylinders were the first thing used by the Folklore of Ireland Society collectors. And with each new technology that came along, which moved to reel-to-reel tape, to cassette tape, to digital things, the collection process took advantage of it.

And so, there is a really, just inexhaustibly rich archive of Irish folklore in what is now called the National Folklore Archive, inherited from the Irish Folklore Commission founded by Delargy, or stimulated by Delargy. But this thing, you know, this miracle, that it was conceived of, and it was executed to actually get the storytelling tradition recorded on the medium of film while that tradition was still alive and didn't have to be reproduced, is kind of a miracle of folklore collection, and something to which we owe, you know, an eternal debt to Delargy and to Flaherty, and then to Robinson, for bringing it to us. And then to whatever it was that kept it in that can, looking just, looking just fine, all of that time, and then to the finding of it. And I have to say it's been absolutely a revelation to be able to work with all of these people, and sort of learn the whole new world of film preservation, and the whole new world of these treasures that we have here. Thank you.

[APPLAUSE]

Haden Guest 54:44

We're happy to take any questions that anyone might have. But I just first want to, just to mention, an equal partner to this whole project was Leslie Morris, Curator of Modern Manuscripts at Houghton Library. So she didn't speak here today, but I want to give her a round of applause for all of her help.

[APPLAUSE]

Haden Guest 55:05

And yeah, so there are questions? No, we have a microphone. Then everybody can hear, that would be good.

Audience 1 55:11

I just wondered if you could say where the print, the 35 millimeter print, is going in Ireland? To whom?

Haden Guest 55:17

The 35 millimeter print will go to the Irish Film Institute, which is in Dublin. I'm planning to actually present the film on the Aran Islands, on a date to be decided. Hopefully, very soon.

Audience 1

[INAUDIBLE]

Haden Guest

What’s that?

Audience 1

[INAUDIBLE]

Haden Guest

I hope so, yeah. But then there are also, a 35 millimeter print is going to the Austrian Film Museum in Vienna, and to the Cinemateca Portuguesa in Lisbon, too. Those are two institutions very much, and who have a deep appreciation of Flaherty, and we think it's very important that the film, as film, is in other institutions that share our mission to preserve the film experience. Other questions? Yeah.

Audience 2 56:12

So just a question about the film itself. So the original, now where is that going to be held?

Haden Guest 56:18

Great question! Yeah. So because we do not have, Harvard does not have a nitrate vault, this print is now at the George Eastman House, which has one of the most important collections of nitrate film. It's on deposit there. And we are very happy that it's in that collection. Do you want to say…?

Elizabeth Coffey 56:42

Yeah, nitrate motion picture storage is super, is also incredibly difficult. And there's a lot of laws around it. And so there's only a handful of places in the United States where you can legally store it.

Haden Guest

USC, right?

Liz Coffey

So there's, well, there's USC, actually, the University of South Carolina actually has a newsreel nitrate film collection. But apart from that, it’s the Eastman House, MoMA, UCLA, and the D.C.

Haden Guest

Library of Congress

Liz Coffey

And Library of Congress. So there's not a lot of places. But so, when people find stuff, that’s generally where they end up. And they have a lot of relationships with archives, where people have a collection on deposit. The Harvard Film Archive actually has a number of nitrate prints at the Library of Congress right now. So it's pretty common.

Catherine McKenna 57:36

I have a question for Liz. And I don't know how it is that it didn't occur to me to wonder about this until yesterday. How did we get it to California, this [LAUGHS] flammable thing?

Elizabeth Coffey 57:53

Well, we have, a couple of people on our staff have been trained in hazardous materials shipping, which is extremely expensive, and it has a lot of rules around it. So, to ship a reel of nitrate, it goes through FedEx, it goes, you know, it goes on their fastest route, and it has a huge amount of odd packaging, and lots of red stickers that say “flammable solid,” and stuff like that. So, yeah, we can do it. But unfortunately, the person who was our main shipper just took a new job. So she's not here anymore. But we're working on training someone else to do it.

Haden Guest 58:31

You know, there's a, actually at the George Eastman House, they're now doing something called the Last Nitrate Picture Show. They're doing a festival, it just ended, the first one, which they’re going to do every year, where they screen nitrate prints. And they're actually getting those prints from all over the world. They showed prints from Norway, from France, and from UCLA, from the Library of Congress. So it's still alive, nitrate film, and certainly the appreciation for nitrate is very much alive as well. So. Other questions?

[INAUDIBLE QUESTION]

Haden Guest

A nitrate print in beautiful shape, I mean, actually, there's a higher silver content. And I mean, I saw absolutely, I've seen some absolutely beautiful nitrate prints. One of the most beautiful was a print which belonged to Hal Wallis, who was the producer of Casablanca, and it was his personal copy of Casablanca. And it is so rich, like it actually glistens, and it moves differently. I mean, one of the things with, I mean, I think the, one of the joys of film as sort of photochemical art, is the way in which the image moves, the way in which shadows and shapes take life, and take form. And nitrate has a particular quality. There’s this, I think, black and white, it's just absolutely gorgeous. Color though, is also incredible in nitrate as well, too. So oftentimes, nitrate prints were hand-tinted, hand-colored. And those are just objects of rare and dazzling beauty. So, when you see a nitrate print in great shape projected, it really is something that there's no equal to.

Haden Guest 1:00:36

Any other questions? David? Go on, ask! [LAUGHS]

David Pendleton 1:00:44

Well, given that you were both talking about, I'm playing devil's advocate here, given that you're both talking about

Haden guest 1:00:48

Actually don’t! No. [LAUGHS]

David Pendleton 1:00:50

Well, that's why I stopped.

Haden Guest

I was just kidding!

David Pendleton

Talking about preserving the original experience. I guess the question is, if nitrate is so different from safety film, why preserve it on film, as opposed to going to some sort of digital? I mean, there's already a change, right? It's no longer the original. Or...

Haden Guest 1:01:07

Well, I mean, I think obviously, you have to draw, you know, we say the original film experience. To be quite honest with you, the experience of us in this room is very different from, you know, the experience of going, right, to a theater in 1935. You know, so there we have to draw the line to say that, yes, there's an approximation of that originality. I mean, this is one of the challenges with, you know, silent films, right? When you show silent films that were meant to be shown with live music, oftentimes improvised, sometimes, you know, and actually capture, how do you, you know, actually, recreate that, that sort of, that dimension of the live music, that liveness, that's a real challenge. And so I think it's there, as in this case, where we have to make a kind of approximation, one that remains true to the spirit of it. That's, in this case, this keeping the film, not cleaning it up, I think, was really important. So this has the qualities, also, of like, local film production, that you can see fingerprints at different times in the film. And things like that, that I love, that you actually see the traces of the object itself. But yeah, I mean, I think that now, you know, I should also say, the work that was done by the lab was very true to the image itself. And so, in terms of the densities, and this is something that, you know, we worked on, and we had to send back. You know, we went through a couple generations of answer prints until we were satisfied with the result. But, you know, I think that now that there's still, you know, artists, technicians, who understand, like, photochemical film, and understand, actually, qualities of nitrate, too, I think that we're still able to get very close to that.

David Pendleton 1:02:57

Just as an addendum, I actually think the print is incredibly beautiful. And I've seen worn nitrate prints that are not always so auratic.

Haden Guest 1:03:06

No, it's true. I mean, that's why I say, like it, when it's a film, for nitrate prints when it's something like, in this case, Casablanca, in which, you know, there was a lot of care given to this print, you know, there were a lot of, in the height of the studio era, there were thousands of prints, you know, made sometimes for, you know, given films, not all those would, sort of, were done with the strictest of quality control. But some studios actually took better care, you know, and had their own you know, production. So, certain studios actually, or countries, you know, the quality of the film of the prints at certain periods is, is very, is excellent. You know, before the Second World War, there were different amounts of, the print, the amount of silver in the prints went down quite a bit because of rationing, and things like this. So, you see, there are different qualities, and characteristics, and sort of personalities, to film stocks at different periods of time. And those are a real challenge to preserve. I mean, there are a lot of now extinct color formats, Technicolor to be one of them, Kodachrome being another one, and so, and reproducing the quality of those colors is also really difficult. Some say that, you know, working with digital means you can get very, very close to that. You know, and I'm starting to see, we're seeing some results that are really quite incredible. So...

Are there other questions?

Audience 1 1:04:41

In a slightly different direction. I wonder if this fabulous experience, and this incredible discovery, has led to thinking about, across Harvard, and broader, but across Harvard in terms of our collections that we think are books. I know that a lot of people like Liz will talk at Preservation meetings and things to other people who are, have their own individual collections. I wonder if there any more films and obviously nitrate, in particular, would be a good thing to know about if you've got a paper collection?

Elizabeth Coffey 1:05:14

Oh, every library at Harvard, and every department at Harvard, has film. It was as common as having a book. 16 millimeter is everywhere, for sure. There is, I can't think of any department not having film, it would be completely impossible. So, I mean, everybody has it. Most of them know what it is. If it's 35 millimeter, most librarians know that there's a possibility that it could be nitrate. So people are moving forward with that, there's been some work from Preservation to work with different libraries about motion picture and audiovisual materials. And that's certainly something that we've been talking about quite a bit. So people are thinking about it. Harvard has a lot to do in terms of audiovisual preservation. And that's especially true for magnetic tape, actually, right now. I don't think there's an awful lot of nitrate around. There definitely is some. I know that the Countway Library had some nitrate preservation in the last couple of years. I'm not sure about anyone else in particular on campus, but it does exist, for sure. Yeah. And hopefully, it's all in beautiful condition. But, yeah. [LAUGHS]

Haden Guest 1:06:24

And I should mention, Robert Flaherty’s first film Nanook of the North, one of his first presentations of that film was at Harvard. And he came with an early version of that film, which he called “the Harvard print.” And so, we're still very much looking for that, because that would be an early version, before the re-edited version, because he significantly changed the film, was released to great fanfare. So I think there's possibly, and I’ll touch wood, there's another nitrate print out there to be rediscovered and rescued. Other question?

Haden Guest 1:06:59

I've got a couple more. It’s right behind you, there.

Audience 3 1:07:05

Sorry. I was going to say, I had a question about the storytelling. And I came to this, I saw the notice through Harvard Film Archive email. And having been a child in Connemara in the ‘70s, and just the fact that, I mean, that the story, it’s interesting, because they talk about it being in Connemara, but then they say Blacksod Bay, which my phone tells me is actually quite a bit further north. And so, I was just wondering about, in the storytelling, is that sort of creation and confluence? The other thing that really struck me is that this is also very much a supernatural story, and yet the interjections of the religious, of the Catholic religious faith, I mean, that that was so completely common in the elderly people that that would be in letters, that they would just be telling stories in letters to America, and saying, oh, and you know, with little prayers, and so on in them, that I thought that, that was very interesting to see it on the film.

Natasha Sumner 1:08:00

Yeah. So to Blacksod Bay, first. I don't think that it's the same Blacksod Bay as the one in Mayo. Because that doesn't seem to make sense. However, Blacksod Bay, while it's the translation that has so far been accepted, but so far, I'm not entirely sure exactly where that is. It does seem to be in Connemara somewhere, and it would be great to find out if anybody knows a bit more. I mean, here we've got an Aran Island storyteller, telling a story about a Connemara man and his sons going out to a different location. So yeah, we've got a little bit of layering going on there and some more information that maybe we could find out talking to locals would be really interesting. The second question, or the second comment, I guess, with regard to the interjections, I think? You were talking about the religiosity. Do you mean when, like, the comments that were made during the song, and that sort of thing? Or

[INAUDIBLE]

Natasha Sumner

Okay. Oh, yes.

Audience 3 1:09:21

Letters from [INAUDIBLE]

Natasha Sumner 1:09:25

Right.

Audience 3

Letters [INAUDIBLE]

Natasha Sumner 1:09:30

Yes, the comments. The comments during the story. Definitely, we had a lot of comments that had a religious element. And yes, my mind went directly to the comments during the song, mainly because that was an issue of translation. And some of them have a religious aspect, as well, that I didn't translate, simply because that's not necessarily what they would mean in a, in a wider context, you know? But yeah, that's the, I mean, religion was a big part of the culture, and religious language was a big part of the culture. So, so yeah, I think that just gives you a little bit of the local flair.

Haden Guest 1:10:15

We’ll do one last question, then we have a little reception outside.

Audience 4 1:10:19

I have another question about originals, because you said there was some mention of, using the digital as the master now, right? Or after the

Haden Guest 1:10:27

As an intermediary, yeah.

Audience 4

Yeah. Oh, so

Elizabeth Coffey 1:10:29

So we have a digital master and a film master.

Audience 4 1:10:32

So another storage question. As far as I know, DRS doesn't take digital video. Is that correct?

Elizabeth Coffey

Yeah, yeah.

Audience 4

So where is that being stored?

Elizabeth Coffey

Yeah, so this is a huge problem, too. Yeah. So it's on a hard drive right now, an external hard drive.

Haden Guest

It’s waiting!

Elizabeth Coffey

Yeah, the DRS is working on it, getting moving images in. If, for those of you who don't know, the DRS is the Digital Repository Service at Harvard, which is where we store large files for archival purposes. So, like photographs, audio files, stuff like that. And we can't do video yet. But we're, it's happening. So yeah, so these files will eventually be stored at the DRS, fingers crossed. Or something like that. I don't know if, they might end, those files are huge! And there, it's going to prove to be a really big challenge for Harvard. So, it's possible they'll, they'll have a similar but different storage system for it. But it looks like they're making some roads for the DRS to handle it. Good question.

Haden Guest 1:11:31

Well, thank you all for joining us this afternoon. We'll have a reception just outside the theater and you're all welcome to join us there. Thank you.

[APPLAUSE]

© Harvard Film Archive

Related film series

Explore more conversations

Ute Aurand, Milena Gierke & Renate Sami

David Pendleton

Nathaniel Dorsky

Godfrey Reggio & Dan Leibsohn