Folklore and Flaherty: A Symposium on the First Irish Language Film. Speakers include Barbara Hillers, Maureen Foley, Kate Chadbourne, Deirdre Ní Chonghaile, and Natasha Sumner.

Transcript

John Quackenbush 0:00

February 19, 2015, the Harvard Film Archive and the Houghton Library hosted a symposium titled Folklore and Flaherty. Participating are Barbara Hillers, Lecturer in Irish Folklore; Catherine McKenna, Chair of the Department of Celtic Languages and Literatures; Maureen Foley, filmmaker; Kate Chadbourne, PhD from Harvard’s Celtic Department; Deidre Ní Chonghaile expert in Aran Island song traditions; and Natasha Sumner, PhD candidate in Celtic Languages and Literatures. The event included a screening of the Harvard Film Archive restoration of Robert Flaherty's A Night of Storytelling. And now, Catherine McKenna.

Catherine McKenna 0:42

Good afternoon. I'm Catherine McKenna. I'm the chair of the Department of Celtic Languages and Literatures and I'm very excited and happy to be part of this event, as I have been excited and happy to be part of the entire process of the recovery of this remarkable film, the first film in the Irish language, Oidhche Sheanchais. I will be chairing the event this afternoon. I want to begin by welcoming you all and thanking you so much for making your way through the continuingly difficult streets, even if they're easing a little bit. It is still not easy getting around, is it? And we're very grateful to have you here. I see so many faces around that I'm happy to see.

I wanted to extend a couple of particular welcomes. One to Breandán Ó Caollaí and his wife, Carmel. Brandon is the Consul General for Ireland in Boston, and we're very honored to have you here. We are also extremely honored to have with us Robert Flaherty’s grandson, Sami van Ingen, who will be part of the Film Archive’s ongoing Flaherty festival. He'll be introducing the screening on Friday of the film Moana and on Saturday of Elephant Boy. Several of you have asked me whether the screening of Man of Aran, which had been scheduled for this past Sunday will be replaced. And the answer is “Yes, it will.” And the date for that will be announced on the website of the Harvard Film Archive. Okay, so that will happen.

But meanwhile, what that means is that our event today is the actual, if you will, premiere of this lost film, [APPLAUSE] which is to say if you weren't in Bologna last July at Cinema Ritrovato. Those of us who are involved in this process, were very put out that the director of the film archive, Haden Guest, got to go, and we just all stayed home and waited for him to come back and tell us about it. But if you weren't there, then chances are very good that you have never seen this film before. Because it certainly was thought that the last copy of it had vanished from the face of the earth in 1943. So the plan here is that we start by doing what we've come here to do to see this film. And after we look at the film—it's quite short, as you may know—then, I have a wonderful group of five very knowledgeable people here, two of whom have traveled all the way from Ireland to be with us today. And I'm very grateful to them, particularly, to Deidre Ní Chongaile and to Barbara Hillers for being here. And after the film, each of us will speak briefly and then—I'm sorry, then I'll break the microphone—and then we'll have some more general conversation. And then before we split up, once there's been a little bit of that context provided, we thought it might be a good idea to screen the film again, something that we have the luxury of doing given the fact that it is so short. So without further ado, then Clayton, if we could start the film, here we go. Enjoy it.

[APPLAUSE]

Catherine McKenna 4:50

So there we go. Pretty, pretty exciting, huh? I'm just gonna say a few things. In some cases, I'm repeating which you've already read on those cards. The film was made in 1934 when filmmaker Robert Flaherty was in Ireland, when he was specifically on the Aran Islands, filming Man of Aran, although planning for this film had begun several years earlier. The film was commissioned by the Department of Education of the Irish Free State, specifically as a film in the Irish language. And it was decided to make it a film of a traditional storyteller telling a traditional story by a traditional fireside to an audience representative of the sort of group that might have gathered in rural houses in Ireland to hear stories of this sort. And that went on even as late as the 1930s and beyond. We've seen the name James Delargy on the cards. If you're not familiar with James Delargy or Seamus O Duilearga. He was the founder of the Folklore of Ireland Society, of its successor the Irish Folklore Institute, and then finally of the renowned Irish Folklore Commission. So throughout his life, he was at the center of probably the most ambitious project of collecting oral traditions ever mounted. In a little while, Barbara is going to tell you some more things about Delargy and his work with Flaherty on this film. James Delargy was friendly with Harvard's Professor Fred Norris Robinson, who was in turn a great friend of Delargy’s mentor, Douglas Hyde, who was himself among other things, a great collector of Irish traditional material. So Fred Norris Robinson or Fritz Robinson, was a Harvard BA, MA, PhD in English, who then after finishing his PhD, went off to Freiburg to study Irish with the renowned philologist Rudolph Thurneysen, and he returned to Harvard in 1896, and introduced the study of Irish to Harvard at that time. We absolutely regard Fritz Robinson as the father of our department of Celtic Languages and Literatures, not only because he taught these courses until his retirement in 1939, but because he also funded one of the two professorships that made establishment of a department possible. That endowment became formal when Robinson died in 1966. The professorship is named for his wife, Margaret Brooks Robinson. And you can imagine how exciting this is for me to be holding that professorship now and talking about this. Anyway, it was Delargy, his friend, who told Robinson about the film, and suggested that he arrange for Harvard to buy a copy. The price was twenty pounds. Robinson had acquired other materials for Harvard in the Irish and Celtic area, including several manuscripts written or owned by Douglas Hyde that are now in Houghton Library. He also gave Harvard his own book collection, which is the core of the Fred Norris Robinson Celtic Seminar Library, which we call the Robinson Room, on the top floor of Widener, and he also was responsible for seeing that Harvard bought this film. Harvard's copy arrived in April of 1935, just a month after its premiere in Dublin. It was housed in Widener Library until 1956, and then it was transferred to Houghton Library, the rare books and manuscripts library. It was cataloged in the old card catalog, but when Hollis, the online catalog, was developed, this film along with a number of other oddly shaped and categorized objects stored in the Z-Closet, did not immediately make it into that catalog. So the film first appeared in Hollis in late 2012. Barbara Hillers, who will be speaking to you soon noticed– She was browsing the list of the thirty-six Irish manuscripts in Houghton—as one does or as Barbara certainly does—browsing the manuscript list from time to time, and suddenly there were thirty-seven and one of them described as a film in a locked box, Oidhche Sheanchais. It was Barbara's alert that initiated a collaborative scramble for restoration funds involving Houghton Library, the Harvard Film Archive, the Celtic Department, and then ultimately the Provostial Fund for the Arts and Humanities as well. So it's been a long road since we began this process in the summer of 2013, but here we are with this great final product. I'm now going to yield the floor to Barbara Hillers who is Lecturer in Irish Folklore at University College Dublin, formerly of the Celtic Department here, and still our beloved associate of the department. She works with the National Folklore Collection in Dublin, and she's learned a lot in those archives about Delargy’s work with Flaherty on the film and many other topics. So, Barbara.

[APPLAUSE]

Barbara Hillers 11:14

Hello! It's so lovely to be back here and very exciting for me to see all that white stuff out there! I know you're not so excited about it anymore, [LAUGHS/LAUGHTER] but I haven't seen any snow since I moved to Dublin. So first of all, I just wanted to extend my really heartfelt thanks to Catherine, because when I wrote that email, I upped and left to Dublin and left it to the home team to pass around the begging bowl. And so thank you to Catherine and everybody who was involved on this side of the project. And it's just magic for me to sit here and see the film.

So I want to build on what Catherine said about the making of the movie and in particular zoom in on the relationship between Robert Flaherty and James Hamilton Delargy, Seamus O Duilearga. Oidhche Sheanchais is in every way a collaborative venture, and also collaborative to the extent that it really draws on the creativity of the storyteller and the singer. But I'm not going to talk about those, but my friends will. So I just wanted to focus on what we can gather from the Delargy/Flaherty correspondence that is unpublished in the National Folklore Archives in Dublin, to throw light on the making, and on the significance of the movie for both people. And I wanted to make really two points. One, that some of the critics—as Brian [UNKNOWN] has pointed out—seem to imply that Robert Flaherty looked at this as a very dégagé attitude, and wasn't really very much interested in it, and the evidence clearly suggests the opposite. And secondly, it's very clear from the unpublished materials that Delargy’s role was far more critical and crucial to the whole project than we had thought previously. And I want to wrap up with just remarks on what this means not just for Irish folkloristics, but also for folkloristics in general. So what we gather from the correspondence which spanned about two years and between the larvae and the entire Flaherty household comprising his brother David Flaherty, his wife Francis Hubbard Flaherty, is that they, the two men, developed a very close and cordial relationship that was mutually respectful and professionally engaged. The Delargys stayed with the Flahertys a number of times in Kilmurvey. And Robert Flaherty’s attitude to the making of Oidhche Sheanchais was clearly very engaged. I want to quote just one little thing that Deirdre has also spotted in the correspondence. When the project was made, when the Minister of Education approached Flaherty, because he was world famous and out there in the Aran Islands, he just wanted something promotional with Irish in it, and it was actually Flaherty who suggested choosing a storytelling event. So it was his idea. And he was very involved in finding a storyteller. And that was really where Delargy came in. He was a man that the Ministry of Education instantly said, “You have to work with this person.” And Delargy and Flaherty together then embark on this quest to find the right storyteller. Several great traditional storytellers were interviewed and shot and they got funded for this; we have the expense forms. And in the end, of course, it was Seáinín Tom Ó Dioráin, an Aran Islander, who got the job, and you have seen his acting skills.

But what it shows about how Delargy worked, is that he instantly recognized the opportunity it gave him to document a genuine storytelling occasion, a storyteller. And those ten days that he spent in London to shoot the movie, he also recorded Seáinín Tom Ó Dioráin for his own burgeoning folklore archives, telling another telling of the same story, and he brought him along to a professional commercial gramophone company, and had him recorded on disk. So these ten days also saw the recording of the first time an Irish story had ever been recorded on a disk. And this is who he was. He was a man with a mission, and he found Flaherty clearly excellent to work with. And I am wrapping up now… with just consideration of what this means for Irish storytelling. As a folklorist, I just thought, “Well, how far do we go back with film, you know, storytelling performances on film?” and it's actually a relatively recent thing. And I kind of hope that some of you will come back to me and say, “Well, there were notable early exceptions,” but according to one writer on folkloric film, Sharon Sherman, the earliest sort of standard, the invoked instance, is Alan Lomax 1935, recording Lead Belly. So we are actually one year before that. And what is remarkable about this particular performance is that even though the term documentary was less than ten years old at the time when Oidhche Sheanchais was shot, already we have someone here, who actually portrays a real, genuine performance. And the point about that is that Delargy of course, would be interested in just documenting a genuine performance, and that Robert Flaherty—who might have had a different kind of artistic agenda—he didn't, of course, know Irish and he just let them get on with it. Soa critic at the time had suggested “Why didn't they cast the more handsome Tiger King instead?” but the point about the whole thing and why they so desperately wanted a real storyteller is they didn't want an actor learning by heart a story that someone else had written. They wanted an actual storyteller, and that's what they got. And that's why I think this little modest, shoestring operation was nothing short of revolutionary.

[APPLAUSE]

Catherine McKenna 20:16

Thanks so much, Barbara. So, the film as it was originally screened in Ireland in 1935, did not have subtitles. I don't know if that occurred to you. It was pretty obvious to us when we started the restoration process that subtitles were in order. And I'm very happy to say that in the digital version of the film, that will be available with subtitles in Irish, because it seems to us that subtitles in Irish are really important to any function that the film has to help learners of the language or speakers of the language. I mean, that 1934 sound quality, even after restoration is not, pellucid, shall we say?

Anyway, so Natasha Sumner, who is a PhD student in the Department of Celtic Languages and Literatures just finishing up a dissertation that deals with Irish and Scottish folklore. She was—and I hope she'll forgive me for it—eventually, she was recruited to be our subtitler. I didn't know what that involved, nor did she. So I asked her and she said “yes.” And now, she's going to tell you a little bit about that process and other things that she would have to say about the film having lived intimately with it for the last year or so. Natasha.

[APPLAUSE]

Natasha Sumner 21:48

Okay, as Kathryn just told you, in May last year, she sent me an email and asked if I would be interested in getting involved with the subtitling of this film. And at the time, I was in Edinburgh, frantically digging through folklore archives, and trying to finish up dissertation research as quickly as possible before I was going to have to leave. So adding another thing to my plate was not necessarily what I wanted. But I immediately said “yes” to this project, because this is just such an exciting find. It's such an important find. I’d known the fact that people had been searching for this film for years, and all of a sudden, it turns up. So I was very enthusiastic to get involved in this. And I jumped into it right away.

The first thing that needed to be done, of course, was to get a full transcription of the film. You've probably noticed, if you speak any Irish, that it is dialectal. Of course, we've got an actual storyteller from the Aran Islands, so that's not a surprise. You'll notice listening to me right now that I am not an Aran Islander. I'm actually from Western Canada. However, I did learn Connemara Irish, which is the dialect of that region. And so I was helped out a little bit by that. I was also helped out a great deal by the fact that the text of the tail had been printed before. It had been printed in December 1934 by the Irish Free State Department of Education, in this little pamphlet. Right here, we happen to have a copy, and I'm sure you can't see from back there, but trust me, this is the text that was sent out to schools for the use of students. It was expected that students would go on the encouragement of their teachers, and view this film on their own time and imbibe the culture and the language and learn a little bit about their heritage. So this was released. The text was also printed in the Irish press, and it's been reprinted a couple times since then. So I had a good deal of help from that. The thing is, this text is only the story. It doesn't contain the song. And there were a couple omissions, very few. A couple of the interjections, essentially, was everything. So I did have to pick those out.

With regard to the song, as I said, it wasn't previously transcribed. In fact, it wasn't even mentioned in any of the press releases. So prior to the rediscovery of the film, the only indication that we had that there was going to be a song was from some of the reactions, commentary in the press afterwards. So trying to figure out what this was was kind of important. And I took down as much as I could. And I had a little bit of help with that as well. I contacted primarily first and foremost—and I'm hoping he's here but I haven't seen him—Michael Newell, former president of Cuman na Gaeilge in Boston, the Irish language society in Boston—and got him to help out. And I got him to help out primarily because A. he's from Connemara, and B. he's a Sean-nós singer himself, a traditional Irish singer. So he was a great help. So if any of you know him, and I'm sure some of you do, do tell him “thank you” for just picking out some of the tricky bits in the song. I also contacted some of the people that I know in Ireland like Deirdre, who is going to speak to you, who actually made the idea of what this was, and definitely helped me along quite a bit. So once the song was transcribed, the tail was transcribed, we had a text. This was great. We had to think about how we were going to present it. With regard to the Irish text, you'll have noticed—if you know any Irish—that the title on screen and that little introductory bit that runs down the screen is in sort of a pre-standardized Irish. It’s the old spelling conventions. You obviously haven't seen the Irish subtitles, but for the Irish subtitles, we had to decide, okay, do we stick with that because it's already an integral part of the film? Or do we modernize? Do we update? And we made that decision, partly due to the fact that subtitles have to be short and comprehensible on screen, so the shorter the better. And the updated orthography cuts out a little bit of the extra letters. So that helped. And we also had to think about the fact that a good deal of our audience that would be looking at the Irish subtitles were likely to be Irish language learners who had learned not the old spellings but the new ones. And so we made the decision to update the language and to go with modern standard orthography there. Now with regard to the English translation—which I also did—there were different concerns, and mainly to do with audience. So with any other Irish language film, I think you could probably assume that the audience, while they might not have a great grasp of Irish—which is why you were providing a translation—they would likely have a bit of knowledge about Irish traditional culture. With this film, because it's a Flaherty film, we couldn't necessarily assume that. We had to take into consideration the fact that people were going to be watching this simply because Flaherty made it. And so we had to strive for the greatest clarity possible in the translation. So I guess one of the things that got kicked back and forth a little bit was, for instance, this phrase, píce agus an splanc, that is so integral to the story, and that I translated as “the pitchfork and the lit sod of turf.” Now, this translation loses a little bit of the nuance. Píce definitely can be a pitchfork. It also means pike. And so listening to it in Irish with both of those meanings in your head, you get this metaphorical idea of the pitchfork being used as a weapon of war when it's being thrown. And there was really no way to bring that into English. Also splanc literally translates as ember. And it would be perfectly fine to say “ember” if I was presenting this to a Connemara-only audience, because they would immediately go “Oh, yes, I know what you mean.” That's a sod of turf that I've pulled out of the fire. However, in a wider audience, of course, ember could mean you know, your ember could have come from coal, it could have come from wood. So this would create confusion. So I had to be very clear about this. So that was just some of the things that we were kicking around.

And I was in contact with people to try and make sure that we got this clarity that we were striving for, such as Barbara at the Irish National Folklore Archive at University College, Dublin. And so, once we got texts in Irish and English that we thought were acceptable, the final thing that had to be done was formatting and timing these texts, so that they would show up on film when they were supposed to show up on film. And of course, the Film Archive folks helped out a good deal with that. However, it turns out that neither they nor the post-production company were Irish speakers. Surprisingly enough! I know I was just flabbergasted. [LAUGHS] Which meant that I was required for that as well. And I learned quite a bit that I did not know before about film production, or at least about subtitling of film. I learned about counting frames, because I had to track the entry and exit times of every little block of text down two frames per second. And of course, that took a few tries. And let me tell you, timing a ten-minute film does not take ten minutes. And if you are brand new to the process, you don't do it just once. So, that was a learning experience for me, and it was a good learning experience. And I'm glad that we've gotten a nice, acceptable end product out of it. And I just want to conclude by saying that over the course of this last year, I feel like I've gotten to know Seáinín, Maggie, Michaeleen, Tiger, and Patch pretty well. And I'm really, really happy to have been able to introduce them to you like this.

[APPLAUSE]

Catherine McKenna 32:15

Thanks, Tasha. Next up, Maureen Foley. Maureen is a filmmaker whose two feature films to date, Home Before Dark and American Wake, both have Irish American themes. Her next film project would have a very definitely Irish theme, and we're hoping for the success of that as soon as possible. Maureen actually literally embodies the connection between fireside storytelling and the visual storytelling of film. Her great grandfather Máirtín Ó Conghaile was an Aran Island storyteller like Seáinín Tom in the film. Máirtín’s stories were collected in the 1890s and eventually published in the 1990s under the title Scéalta Mháirtín Neile. Maureen's no stranger to the homegrown session, either; she is a fiddler as well as a filmmaker, a student of the late, great, Larry Reynolds, whom I know many of us know and miss here. So, Maureen.

[APPLAUSE]

Maureen Foley 33:42

In this company, I wouldn't say that I'm really a fiddler. I'm a competent session player. That's all! [LAUGHS] Barely.

As Catherine has indicated, I'm here for two reasons. And people other than I can tell you a lot more about this film. So I'll make my comments brief. But I wanted to share a couple of things pertaining to Aron culture that has come to me through my family. And also to talk a little bit about how this film– The way it was made, actually, emphasizes the point that Barbara made that Robert Flaherty took this material very, very seriously and really did deeply understand things about Irish culture. And the way that the film is shot and put together tells you that.

So most people who know my name is Foley and that I came from the Aran Islands say, “That's not possible because there are no Foleys on the Aran Islands.” And that's actually true. The family name is Folan or [?Ó Cualáin?], and I'm a Foley because my grandfather and his brother came over and met up with an immigration official in Bath, Maine, who said that there weren't a lot of people named Folan here and if they wanted to stay, they had to take the name of Foley. [SCATTERED LAUGHTER] My grandfather, having had enough of Inishmaan said, “I'll change my name no problem.” His brother refused and spent six weeks in detention after which he was shipped back to Inishmaan. So, our family on Inishmaan is the Folan family and in the United States, the descendants of my grandfather are called Foleys.

Our family lives in the oldest surviving house on Inishmaan. My cousin [?Máirtín?] is the ninth generation of our family living there. Two brothers came over from Connemara and built two homes on Inishmaan and one survives and that's our family home. And if you go and spend any time there, you're not really too far from this scene. The hearth is still there after an accident with embers about two years ago. It now has a stove in it, but until two years ago—it had coal now—but it looked just like that. And an evening couldn't pass sitting by the fire where my cousin [?Máirtín?] didn't launch into one of the stories like this, usually the one about in 1888 my uncle Patch was in a canoe when the currach overturned and the seed potatoes were not able to come to Ireland. And the drowning that resulted in the family was one of the antecedents of Synge’s play Riders to the Sea. That and another drowning. And the story I'll tell you really briefly is that a currach of seed potatoes was coming over from Clare and on the shore in Inishmaan were my great uncle Patch Folan, a man named Coleman McDonogh, and another man from Inishmore. And they saw the currach getting into trouble. And they got in their own and rode out to try to save them. And the cargo returned and my great uncle and his people in his boat all drowned, and the people who had the seed potatoes made it safely to inishmaan. So it's perceived widely—I guess, accepted—that Riders to the Sea, John Millington Synge’s play, came from that incident and one other drowning, were sort of put together.

Synge is the other link to the other side of my family from Inishmore, which goes back to the storyteller, Morton [UNKNOWN], who was my grandmother's father. I knew about him first as a storyteller through the writings of John Millington Synge. In the book The Aran Islands, he's called “Old Blind Máirtín” and he teaches Synge some Irish, and he shares his stories with Synge, and one of those stories went on to become The Well of the Saints, Synge’s play. So if there's any doubt that the Aran Island-John Millington Synge connection was tight, and that he really drew deeply on his material, you look at the two sides of my family and there's a connection to Riders to the Sea from Inishmaan and a connection to Well of the Saints from Inishmore. So that is my, sort of, history. And my great grandfather was a person very much like this.

I'll just take a moment to share something which I think—Deidre’s also a fiddle player. She's probably really a fiddle player, as opposed to me, I'm not really a fiddle player. But it was very interesting to me to watch the way this film was actually put together. And I noticed a lot of parallels about the way people share evenings, that the film demonstrated, which come right down to an Irish session. For those of you who follow Irish music or are familiar with this world, in Boston, especially thanks in large part to the dear Larry Reynolds, the Irish session culture is a vibrant tradition which continues. There isn’t a night or a day in Boston, if you know where to look, where you can't find an Irish session. And they usually take place in pubs, occasionally in halls, and they're open to anyone who plays, sings, wants to hang around, wants to tell a story, would like to declaim something, would like to recite a Yeats poem, and they unfold very much the way these evenings unfold. Anyone is welcome. That's not to say that there isn't a real structure which governs the session. They're very hierarchical. Where you sit is very important. And there are seats of honor close to the hearth, which in the case of the Irish session is the table or the central spot where the people who are. It isn't necessarily that they're the best musicians, although they might be. They're the people who are honored most in the community. So you might have someone who's eighty-five-years-old and a terrible singer, but they have a particular spot that belongs to them at the session. And they would be among– It's a combination of skill, much less though, than being honored by the community. You don't perform at an Irish session; you share. So if someone shows up in an Irish session, as often happens here, Berklee students come and will, you know, start to perform. But that's really beside the point. You're there to share with your fellow friends, the way they share with you. And the purpose is to build the community and to downplay anything having to do with performance and make it much more about You played for me, now I'm going to play for you. So it doesn't really matter if you're that good. Children come and play. And it's all really about the sharing of the communal experience and the way in which that evening together binds the community together. And believe me, in Boston, the session culture binds the Irish American community together every bit as much as what you've seen there.

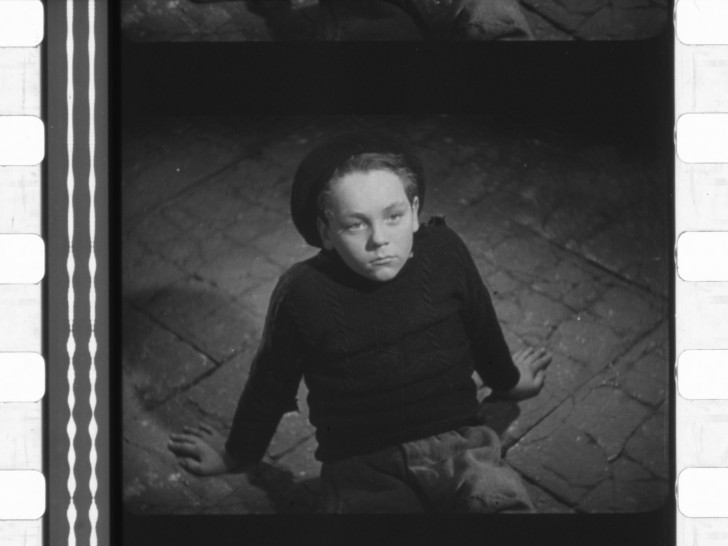

I just wanted to say when you watch the film again, you might be interested to see how the filmmaker was very careful to make that point in the film. So you can set up the camera anywhere when you're shooting. You can have close-ups, you can have extreme close-ups, you can have the camera far away, take in a wide-shot. And what was so striking to me was watching the film, it was designed to show what the evening was really about, which was the communal experience and the people and the experience of people listening to the story. So when you watch it again, you'll see there's sort of a wide shot that sort of establishes that we're by a fireside and everybody's in it. There's a quick shot of the storyteller. But then we really don't see him until almost nine minutes into an eleven-minute film. We see him in the wide-shot, but we never see his face. When we see him, we see the whole picture of him with his hands. Whereas if you look at the listeners to the tail, you see all of the emotion on their faces, extreme close-up. So you see the little boy—coached, obviously, but you know—looking scared at the right moment and so forth. But you really feel that what he was saying in the film by the way he shot and edited the film, was that this is not about performance. It's not even about the storyteller. It's about the way in which these evenings—which continue today in Boston and everywhere else where session culture is alive—they serve a larger cultural purpose, and that is to bind us together as a culture in ways that we support each other and entertain each other through the long nights of winter. So thank you for inviting me.

[APPLAUSE]

Catherine McKenna 42:44

Oh, thanks for that, Maureen. So next up, Kate Chadbourne. Kate Chadbourne is a woman of many parts. She is a superb musician, both vocal and instrumental. She is a poet. She is a legendary teacher. She is a folklorist. And as a folklorist, she is, as it happens, particularly knowledgeable about the general category of the story that Seáinín Tom tells, which is known as a type, as “the knife against the wave.” And I'm not sure whether that's what she is going to talk about or what, but anyway, here's Kate Chadbourne!

[APPLAUSE]

Kate Chadbourne 43:32

Thank you so much. You know, I love what you said, Maureen, about the bringing together because that's what today is, isn't it? I mean, this feels very much like we are part of a cèilidh. And if truly the hearth is here, Catherine, you're sitting in the seat closest to the fire! [LAUGHS] Just as it should be. So as Catherine said, I'm not part of the restoration of this film. I just have the pure dumb good luck to be a fisherman's daughter who's interested in sea stories and sea folklore. And I took a special interest in this story which is called sgian an aghaidh na tuinne, which is “the knife against the wave.” And it’s a story that's told all over Europe, but it is, I think, especially, we could say, found in Ireland, where we have at least 150 versions– Oh, sorry!

Is that better? Can you guys hear me up at the back there? Okay, pretty well? I'll talk up a little bit. You sort of rest on your laurels if you have a microphone like, “I don't have to yell.” Anyway, there's 150 versions of this. And it's a kind of a very flexible frame because people can put all kinds of things in it, if you know what I mean. So the general story is always something along the lines that a fisherman goes out to sea, a wave comes up—sometimes there's one, sometimes there's three—and then he throws something as you saw in the film. He threw, as Natasha explained, a pitchfork and burning ember at the wave. Often though he throws a knife. Sometimes he throws his boots, which I love. If you're that desperate, first one boot, then the other boot and then the knife that's stuck in the gaff, and there it goes. And then the wave dies down, as you heard when Seáinín says, and you know, “It melted down.” Did you see that? He melted down, and then they go home. And I think that's an important part of the story is that you return to the hearth. And this comes to the point I want to make is that you need to return to the hearth because you are an earth person who does a pretty wild thing, and you step out on the sea in this other realm, where there are different rules and where there is a different, well, a different environment. And so you're a guest. So they go home, and they're hanging around the hearth, sort of re-earthing themselves. And then there's always the old knock on the door, and somebody turns up, and it's always the man on the big horse, often the white horse. Here, the coal black horse, with a snowball—I love that—on his head. And always this noble person inviting you to come. Somebody has to come because this missile has to be withdrawn from, as you heard. And in many of these versions, the person who brings you along is actually the brother. In this version, did you notice? It was the king and she was the queen. I have my own questions about whether this was maybe a little bit easier for James Delargy, because it wasn't– I think there's a very, I'm just gonna say, a sensual aspect here that we– Sorry, but there is! And so in this case, it's the youngest son of the famous fishermen and invited to come and draw that out. And so it's clear like this is not a potential sexual relationship that's going to happen here. So my feeling about these stories is that they really show us a way that fishing communities and fishermen kind of came to grips with their relationship with the sea. And that would have been everybody. Really like 19th century, certainly Aran Islands people, but lots of coastal communities, everybody was involved with the sea. Everybody was mending nets or drying fish, right? Or bringing up seaweed, everybody was part of that. And so I think there's a sense of an imaginative reengagement through these stories with the sea. There's a whole body of folklore that underlies this story. So many things. Now you might have been thinking “Gracious, there were, what, seventy-eight widows on the strand!” Right? And a whole scad of orphan children. There's a seanfhocail proverb that says, [IRISH PHRASE]: the sea must get her own. Now, there's an old story that says when God made the world, he set a king to be the king over the sea. And the deal they made was that the king would never drown anybody. If he did, there’d be trouble. Now, of course, what is the very first thing he did? Because he's the sea, he drowned somebody and they say now he's all curled up in a periwinkle waiting for judgment, because he knows is in big trouble.

So that's the kind of relationship [with the] sea as a dangerous neighbor. But I want to say, even though we have a king of the sea here—who's wearing his big Caroline hat, and he is one of the sea fairies. He's one of the uaisleacht na farraige, “the nobility of the sea.” Really the heart of the sea, the one who has a pike sticking in it, it's a chick, right? It's a woman always, because there is this kind of being drawn out into this other realm that we have to figure out. And I think a question that's at the heart of all this is Where do we belong? Now the good fisherman is invited to withdraw that from her heart and says, “I'm going home,” right? Like “I don't belong here. I get that. I don't belong here.” Now, you might be saying, so in this version, I think it's a teaching tale, that Máirtín says to all the sons, “Bring this thing.” Now, why? This is, in my view, asserting what I call the terrestriality—the earthiness—of these boys going out to sea, right? So instead of throwing the boots and the gaff or the knife or whatever, it's “Bring something from the hearth,” literally “Bring the hearth and bring the pike”—so an agricultural tool—bring those in those will keep you safe. And that's not surprising because we have other folklore that says that it was lucky for guys to wear boots with mud onto their boats, because that would sort of assert, its again, where do we belong?, or it was lucky in a lot of other folklore to bring a burning turf onto the boat. So, again, that's sort of the way that I read this. And I see this as a teaching within a teaching, in a way. We're being taught of that relationship as the boys are being taught: this is what you need in order to know where you belong. So it's a great honor to be a part of this. And please, if you do go to sea, I hope you'll bring yourself a pike and a burning turf. [LAUGHS] Thank you.

[APPLAUSE]

Catherine McKenna 50:43

Wonderful. And now, the last speaker before we open to conversation among all of us, is Deirdre Ní Chonghaile who has come all the way from—well, I know she flew out of Shannon. I don't know where you were– You were in Connemara, at any rate! She is a musician and scholar from the Aran Islands. She's the coordinator of an online project. Amhráin Aronn, the Aran Island song project and, as I said before, we're really honored and thrilled that she's come all this way to be with us today. Deirdre.

[APPLAUSE]

Deirdre Ní Chonghaile 51:24

[SPEAKS IN IRISH] I am absolutely delighted to be here. It was magical watching that on the big screen, absolutely magical. I was one of the lucky ones to get the sneak preview a couple of months ago when I was drafted into the crew [LAUGHS] that have been looking after this. And as a fisherman's daughter, I can completely empathize with the stories they're about– I've heard my father talk about having three wives: at the boat, the sea, and my mother. [LAUGHTER] And often he said “Poor Maura came last.” So that relationship is very current, even today. And I was struck, especially, looking at the faces, the close-ups of Patch Ruadh and Maggie. They're acting in a sense, but you can see it in their eyes, they don't have to act around the fear of what will befall people when they venture out in the sea. So, you know, it's very close to home, as you've explained so beautifully.

I could talk about this all day, in which case Catherine's gonna have to prepare a splanc and píce to throw at me. [LAUGHTER] So that's why I've got the phone to remind me to stop after ten minutes. So what I want to do is try to add to what's been said already, and maybe the first thing to start with is that this film springs from a really extraordinary period in the cultural history of the Aran Islands and of Ireland in general. And I think Barbara's comment about it being revolutionary is a bang on the money. And in a sense, the radical nature of the whole effort, I think, relates to the media—or the medium rather—of film. Because there is an excitement attached to that. There's the sense that suddenly, here's this world famous filmmaker going to the Aran Islands. They don't quite understand that he doesn't have sound recording equipment. So that's where the suggestion for an Irish language film being made in Aran comes from. In the end, the technology isn't quite there yet, so the next best thing is to make it in London, in a studio in Islington, and to build a set that looks like it's in Aran, and they've got the pampooties on their feet and the woolens, and everything and the [UNKNOWN] and all, so they pull off the illusion, I suppose. And they pull it off, I guess, as well, because they had experienced people involved. All of the actors on screen appeared in Man of Aran. At that stage, their acting careers were, you know, two years old, really, by that time. So they're old hands, and you know, given the coaching for Michaeleen, it's still, you know, he does his job well, and Seáinín Tom especially. And in my journey here, I had two people in the back of my mind. One was Tom Crean, the famous Kerry Antarctic Explorer, because of the dread of the snow that was going to face me in Boston! [LAUGHTER] And I brought the boots and all! The other person was Seáinín Tom, because as I thought about the long journey ahead, I thought, “This is nothing compared to what Seáinín Tom faced.” And Barbara had explained about the various storytellers that had been interviewed in the lead-up to securing the star of this film, and in the end, the selection actually was a Connemara storyteller named Sean O'Brien from [UNKNOWN] but as happened on the first of January 1934, he passed away. And suddenly there was a film to be made, and there was no star. So a telegram was sent in haste to the school teacher in [UNKNOWN], a good friend of Seáinín Tom's, Joe Flanagan from County Clare, and his job was to persuade Seáinín Tom to fill Sean O’Brien's boots. And by no means was he sort of a poor understudy or anything. He was very near being selected for the film. Delargy was very taken with him. He looked great on camera. You could see, as well, he suited film. If you look at the storytelling that was collected in the Aran Islands, there is some from Seáinín Tom, but there was another storyteller named Darach Ó Direáin who, in a sense, was more famous than Seáinín Tom as a storyteller, and yet he didn't seem to suit the medium of film as well as Seáinín Tom did. So a lot of various factors come into the story of how Seáinín Tom eventually ended up in London. Three times he walked to Kilronan, which is six miles easily, and three times the boat didn't sail. So he had to go back home again, having warmed his body in the hostelries in Kilronan a little bit too well. [LAUGHTER] So he eventually made it to London, and in a lovely turn of events, then, he would frequently visit Joe Flanagan's house. Joe had seven or eight children, he and his wife teaching in the school nearby, and one of the eldest children in that house, [?Dónall?], another school teacher, later wrote a book in which there are beautiful descriptions of Seáinín all through his youth and his childhood and to see Seáinín through the eyes of a child in a sense, sort of adds to the aura he created as a storyteller. And he said it was better to see London through Seáinín Tom's eyes than to go there yourself. So I love the fact that the film has really captured, as Natasha said, a sense of the people themselves, and that, I think, shows Flaherty's relationship with the local community. Yes, he did come in, sort of, this blustering ball of energy and make this extraordinary film. But he really did leave an impression in the island and altered the lives of people forever thereafter,—Man of Aran and Synge’s opus in general—they're the two anchors in the history of the islands for the last 120 years. And so many stories come back to those episodes.

There's an interesting addition here that I want to share with you. It's new research that came about when I went back again to [?Dónall O’Flanagan's?] book, in which Seáinín Tom is described. And there were very few photographs in the book, but there is one of Seáinín Tom, taken in 1926, and he himself is being recorded on an Ediphone machine by a man that you cannot see in the photograph, but it was he who took the photograph, and it's General Richard Mulcahy—a much maligned figure, for many people, in Irish history—but there’s sort of a little known element of his cultural interest is that he had a recording machine, an Ediphone, and a camera. And he both recorded and photographed the storytellers that he documented and the photograph is extraordinary, really, because it shows Seáinín Tom hearing his own voice. And in his face, there's pride, and also a sense of, That's how it's done. That's the way it should be. And that comes across in this film as well.

So we should say, as well, that Seáinín Tom was about sixty-four when he went to make this and it's somewhat poignant that the story relates to a maritime incident and a perilous one at that, because five years later, he himself drowned in a currach with his two friends, the teacher Joe Flanagan, and James [?Ó Flaithbheartaigh?] to a very gifted man, musical man, dancer and carpentry [UNKNOWN]. The three of them went in a currach over to Connemara to go to Croagh Patrick on pilgrimage. And on their way back on the 31st of July, the currach was lost, and the three men were lost. Their bodies never recovered. And Breandán Ó hEithir, the writer and broadcaster from Kilronan, as a child, remembered the currach of being towed into Kilronan by the lifeboat and the words that confirmed their awful fears saying “[?Sí é?].” “That's her. That's the currach.” So it really was an extraordinary turn of events from start to finish.

And the story of this film, it's like a prism, you know, the film is almost like the light. The light from the projector comes and passes through a prism, and it suddenly opens out into Irish cultural history in the early part of the 20th century, which really had its radicals. We talk about 1916 as being a very radical period, but those involved in the creation of the state were radical themselves. I sort of regard the input of media in that—whether it was photographic or recording or film—as enabling those people to sort of flex their maverick muscles in a sense. And the extraordinary thing is that what came out of that is a sense of the local voice. And a voice that didn't necessarily get many platforms thereafter, but for the work of the Irish Folklore Commission, for instance, and thankfully, a lot of that now is being digitized. And we're seeing a whole new generation of people interacting with all of that wealth online in a very kind of, there's a buzz around us. It hasn't gone viral or anything, but there is a definite feeling that there's a new generation, re-energizing the whole effort. So I'm really looking forward to this coming home to Aran, and hopefully elsewhere in Ireland, in Dublin and maybe in Galway, I'm not sure yet, but later this year, so please do tell all your friends in Ireland.

I've been involved in a film repatriation project before, bringing old films back to the Aran Islands. And they really were extraordinary nights that we had in Inisheer and Inishmore. Thoroughly memorable, not just for what was shown on screen, but for everything that happened: all the sparks in the room thereafter and long into the night, of course, as well. So we're looking forward to continuing the conversation around this gem.

Catherine McKenna 1:03:17

You may have gotten the impression from our speakers that I had them terrified with what would happen to them if they spoke for more than ten minutes. And I did! [LAUGHS/LAUGHTER] I’d been working at that for some time. And there was a reason for that. And the reason is that, I really feel that what we really want to hear is conversation for all of us. I mean, yes, you're welcome to ask any of the speakers questions, but mostly we want to hear what you have to say, what you have to add to this discussion. So I'm going to ask Tasha and Maureen and Barbara and Deirdre and Kate to just come up here and face you and then I have some microphones for them to use… Thank you!

Audience 1 1:04:44

[FIRST PART WITHOUT MIC INAUDIBLE] –here in Boston, just as an Irish speaker and a student of the Irish language and indeed, folklore, at a much earlier stage in my life, it is fantastic that Harvard brought us this absolute gem—not just the first movie in the Irish language but such a lively one. It’s the best ten minutes of [?film?] you could have. He’s a fantastic storyteller—as you said, Deirdre—following a [INAUDIBLE] tradition. I just wanted to say, I want to very fundamentally thank Harvard U, Dr. McKenna, and everybody here at the archive for this fantastic gem that you've restored to the Irish people, Irish America and to the global folklore tradition. It's fantastic. The only other thing I do want to say is that Deirdre alluded to the Cultural Revolution, which happened in the 19th century, you know that. And you know, that I think Synge went to the Aran Islands on the advice of William Butler Yeats, and those of us who grew up studying Irish—I grew up in Dublin—we always look to the Aran Islands as this literally almost mythical kind of place, completely bathed in that. But I just also want to situate now—I'm not going to take much more time—but I want to situate that this film and everything that went with it is coming at a time– It's twelve years from independence, 1922. It's a new state. It's trying to create a new cultural identity very much around those things which had been largely lost or diminished in significance. So the west of Ireland and the Connemara Gaeltacht Aran Islands and all the rest of the Gaeltacht around the west coast became absolutely crucial to the reinvigoration of Irish culture. All Irish teachers were obliged to go and spend time in Connemara or in the Gaeltacht to learn the Irish language. So I think this film comes out of a huge context. And as an Irish speaker, as they say, representing the people of Ireland, I'm so proud to see it. And I want to thank everybody involved in any way with restoring this incredible cultural gem. Go raibh maith agat!

[APPLAUSE]

Audience 2 1:07:05

I was wondering, Tasha and Kate, you both mentioned briefly the song, but you really didn't say much about it. Is it also one that is well known or does it seem to be a local top-ten favorite in the Arans?

[LAUGHTER]

Kate Chadbourne 1:07:22

The song is “Baile an Rodhba.” Ballinrobe, a town in County Mayo. A love song. Traditional songs sometimes morph and maybe borrow lines and images and verses from other songs. And the version that Maggie sings is a bit like that. There's bits of [UNKNOWN] in there. And the songs also known as a [UNKNOWN]. So she certainly had it in her own repertoire, and she recorded it again in 1955.

There's an interesting story behind a Man of Aran's coming to America. Maggie, Tiger and Michaeleen made the transatlantic crossing in order to promote the film. And while they were in New York, they were introduced to Henry Cowell the American composer. And Henry and his colleague, Charles Seeger at the New School had created—with Charles's son's help (another Charles)—an aluminum disc recorder. So he brought them into his class and on site in 1934, and made aluminum disc recordings of Maggie and Michaeleen singing that you can hear in the New York Public Library. Anybody can go in and listen to them. I did! And “Baile an Rodhba” isn't in there. What happened was years later—twenty-one years later—when Henry Cowell had married, Sidney Robertson Cowell, Sidney had spent twenty years as an ethnomusicologist and folklore collector—of folk music mainly—as they visited Aran because Henry had Irish heritage. And they came and Henry said the one person he wanted to see in Ireland was Maggie Dirrane. So they came back to the Aran Islands. They stayed in my grandparents’ guesthouse and she procured a machine—that was it, because they were on holidays, and she wasn't supposed to be recording—but she couldn't resist the urge. So they were holidaying, and then they left and then she said, “Henry, you carry on to Germany.” And she went back to Aran to record for about two weeks and an album came out of that. And it's still available. Smithsonian Folkways have it. It's called Songs of Aran; that was the first commercial recording released from the Aran Islands. So that explains what I was talking about Man of Aran having this ripple effect years later. So “Baile an Rodhba” is amongst those recordings. I can't remember whether it made the album cut or not. And Sidney went back there again in 1956 and recorded in Inishmaan, and in [?Cornamona?] as well. So, that's the song.

[APPLAUSE]

Audience 3 1:10:07

Hello. [SPEAKS IRISH] So one of the things that I kind of noticed that was very interesting is that this is a very intimate experience that is very publicly on display. And Maureen, I actually think I know some of your family because I spent a summer on Inishmaan, and I ran into your cousin, I believe. Yeah, I know him. Yeah. But when I was learning Irish there, one of my best, most treasured memories is every day I'd walk down, and I'd sit on the wall, and I would try my terrible Irish with the man sitting on the wall.

Maureen

Was that my cousin [INAUDIBLE]?

Audience 3

Yeah, it was him! And, I remember I'd say, “Cén t-am atá Aifreann?” I would ask what time mass was everyday, like it changed, you know! [LAUGHS/LAUGHTER]

Maureen

[INAUDIBLE]

Audience 3 1:11:05

And the story is a type of synecdoche for me coming into Connemara, into Irish language households and saying, “Hey, speak Irish to me.” And here I was this Harvard student, you know, coming in, and only speaking in the past tense and really making a fool of myself. [LAUGHTER] And, one of the things that I have grown to be very self conscious of is learners kind of like myself busting in and saying, “Hi, I'm learning your culture. Hi.” And so one of the things I wanted to ask is, to me, this is one of the first, sort of, early busting in and saying, “Hey, show me your quaint stories from the Middle Ages.” And, I know that Flaherty wasn't saying that. I just wanted to know if you guys had an opinion on what you thought. The family and the storyteller, if they would have viewed that as an area of pride in showing their culture, or if in the past, it was going to be the same way. The old man on the bench. He always spoke English back to me, because he wasn't going to share his language with me. Eventually he did. I wore him down. [LAUGHTER] But you know.

[INAUDIBLE COMMENT]

Yeah! So you know, it took a long time. But, I wanted to know if you thought that this exposure, in all sense of the word, was a source of pride, or if it is just the tip of the iceberg of people coming in saying, “Hey, teach us,” and then leaving?

Barbara Hillers 1:12:36

Well, maybe I could say something to that.

[INAUDIBLE COMMENT]

Lovely to see you. [SPEAKS IRISH]

If James Delargy comes to you, from Dublin, and always looking, you know, suit and tie… All the collectors for the Irish Folklore Commission were clearly encouraged to be, sort of, part of the middle class—even though they all came from Gaeltacht backgrounds with the exception of Delargy himself. And puts the mic in front of you or the headphone and says, “You are the voice of traditional Ireland,” you realize it's an honor. And of course, as we have been told, you know, the tradition itself has told you all the time, that this is an honor that you are carrying on this story, that neither you nor even the people you learned it from, made up or invented. So yes, you are going to feel it is an honor to share that and this sort of quiet confidence that Deirdre described to you, I think that, for me, sums up the attitude.

Deirdre Ní Chonghaile 1:14:14

The other thing is, as well, that sometimes the question of literacy comes into this, because had someone not had such a grasp on literacy, the opportunity for their culture, their store of tales, to be written down, was just grabbed. And actually, this is a lovely kind of synchronicity—isn’t that the word?—because her great grandfather is known for having said “Scríobh síos é sin, a Dane!” “Write that down, you Danish man!” [LAUGHTER] The Danish man was Pedersen and he was known as “the Dane.” And that was sort of saying, well, that's something worth recording, so they’d say “Scríobh síos, a Dane.” So, it's really funny how that just came right back ‘round where the notion of it being really prestigious, almost then became a joke as well or, a complimentary one, to say “That's a good thing to do,” I suppose.

And the other interesting thing about this is as soon as literacy does become more prevalent, I mean, the man down there spoke about the cultural revival period. The Gaelic league had branches on all three of the Aran Islands, and they talk about having Irish language classes in the islands. That's a bit of a misnomer, really, because what they are is literacy classes. Because you weren't actually getting Irish literacy via the education system. So the opportunity, the excitement that was generated by these Sunday meetings of people giving up their one day of rest to learn to write—or well, at least read and maybe write as well—is really palpable, when you look at those kinds of accounts and look at encounters like the one with Mháirtín Neile or later, whether it's Pádraig Pearse coming as a nineteen-year-old into the island, and the first thing he sees—the image in my head is the cross that his own father caught, that James Pearce made. It's in the middle of the village in Kilronan, and it stands out as you're approaching against the horizon line. And as a nineteen-year-old, that must have made some impression, that his father had already been there before and and then he would have met Mháirtín Neile and [?Mark Sheen?] and various others. And then fast forward, whether it's—again, in any introduction of technology, it's just grabbed because of that sense of authorship and authority. So the first tape recording machine, the first recording device owned by an Islander was owned by my aunt. And listening to those tapes, there is that sense where she went to the local poets, the local songmakers, and there's two of them, they’re cousins and they’re neighbors. Actually, Matt is Patch Ruadh’s son. So the next generation, there's an Islander who comes along with the equipment. And the two of them, the two poets, start to exchange and say, [SPEAKS IRISH]: “Have you heard the latest song that I've made about Aran?” And the other goes, “Oh, no, no,” kind of mockingly sort of, he hadn't heard it, but he probably had. But it's for the tape, it's for the good of the tape. So it's just like this all over again. And then he launches into it, and it's hot off the presses, the latest composition. So it's apart from the notion of them and us and the other. I think the potential that lies in media, as soon as you give people the opportunity is just massive, I think.

Natasha Sumner 1:17:48

I suppose I just had one tiny little thing. And I agree with absolutely everything you've just said. And I know that you were pointing to probably the introductory bit with the comparison to the Middle Ages, and the fact that this has been around forever and this romanticized notion of pastness. And of course, that was a part of the whole folklore collection process: saving this before it disappears, this culture that's about to be lost. And along with that does come some– Well, if you're if you're looking at seeing some depictions that aren't always entirely accurate or friendly… But the thing with this and the thing with the folklore commission is that while that attitude, I mean, it's there in the background. But this sort of recording, the recording of genuine folklore is, of course, not at all patronizing, and it is a way for people to actually share their culture, to speak themselves, as opposed to being spoken for. So that's just the last bit that I’d add.

Maureen Foley 1:19:04

I just want to add one more thing. I think you should keep trying, I think, you know, at least,

I think if you could make a grand statement about temperament, Aran temperament, it's a little on the reserved side. [LAUGHTER] I could be wrong! But I think even when my sister and I began spending time there, it took a while for us to, you know, everybody knew who my grandfather was, and they knew everything and they knew we were related that we were sort of in that way, but it took a while for us to be sort of really accepted by everybody on the island and and I knew I’d finally made it when I was there in the spring and my extended cousin’s back was bothering him, and he asked me if I could get a row of potatoes in for him. So I you know, I spent the day in the garden getting the potatoes in, but it wouldn't have happened the first time I was there, and I think underneath that reserved is a very generous heart but it may take a little trying and I’d keep trying.

Audience 3

I will!

[LAUGHTER]

Audience 4 1:20:13

[SPEAKS IRISH] Patrick [UNKNOWN] here from Inishmaan, Aran Islands with my wife, Gobnait and daughter Aoife. We have another daughter who lives and works here in Boston. I'm delighted to be here today. It's a great occasion. And I know, Deirdre. Maureen Foley, I know your cousin very well, [?Máirtín?]. I went to school with him, to primary school. He'd be around my own–

Maureen Foley 1:20:53

Maybe it was your cousin that asked me to help get the potatoes in!

[LAUGHTER]

Audience 4 1:20:57

Probably! Or my brother [UNKNOWN]. So I won't waste any of your time. But it was great to see that piece of film. [IRISH EXPRESSION] Thank you, Catherine, and to all the other speakers.

In relation to the drownings, well, I heard that story. You know, there are facts in relation to John Wellington Synge’s story and my wife Gobnait, it was her granduncle [who] was the McDunnagh in the currach, so [IRISH EXPRESSION], and thank you ever so much.

[APPLAUSE]

Natasha Sumner 1:21:47

[IRISH EXPRESSION]

Audience 5 1:22:02

[IRISH EXPRESSION]! It was a wonderful film. And thank you, everyone from Harvard and everyone involved for bringing this piece of Irish culture back to life. But I want to ask the folklorists among you about a particular aspect of the film right at the end, where the storyteller has this wonderful self-effacing thing. He says, “This wasn't my story.” And I wonder, is that a typical thing in folklore? Or would you like to talk a little bit about that? I thought was a lovely moment in the whole thing.

Kate Chadbourne 1:22:42

Yes, it certainly is. There are a lot of formulas, sort of, for opening and closing tales. “Ní mise a chum é ná a cheap é.” “I didn't make it. I didn't think it up.” I think what that emphasizes really is the chain of tradition, right? That you're just one link in that chain and paying it forward. And there's lots and lots of other ways of saying that. You can say, “I don't even mind if it's a lie.” “So be it,” right? “If it's a lie, so be it.” So lots of ways to express that. Barbara, is there anything else you want to put there?

[INAUDIBLE COMMENTS]

Well, what Maureen is coming up with here is the idea that—and this is definitely true—I speak as a singer here. You wait as a singer or a storyteller, and I won't speak for you fiddlers, but as a singer, you certainly wait. And in fact, you can wait twice. Right? So Larry—bless his soul—used to ask me to sing. And then you sing your song. And then somebody says, “Sing another!” and you say, “Noooo.” [LAUGHS] You sing once and you do a good job and you're done. And that's just part of your part of creating an evening, just as Maureen said, that you're one little bit of that, and then somebody else's little bit and you wait for that invitation. There's a lot of unspoken, unwritten courtesy at the heart of all of this, but it—I think at the heart of it all—is very generous, and inclusive. Does that answer your question? I have another microphone if you want more! [LAUGHTER]

Audience 6 1:24:26

My heart is just exploding with joy for just all the work that was done on this film, for bringing it to us. [SPEAKS IRISH] I’m a very weak singer, but I just love [?this Irish culture?]. [INAUDIBLE] ethnomusicologist [INAUDIBLE], but it's not important for this, but it's just all of these elements in the same place at the same time, I'm about to explode. At any rate, there’s just a little point of folklore, as well, Kate, that the ember or the sod, and [SPEAKS IRISH]. “Where will your sod of death be?” Do you remember that one? Yeah. And that to me that element of the pike and the sod is also kind of a situating in a danger or death. I just thought I’d bring that joy to you… [LAUGHTER] Can you speak to that?

Barbara Hillers 1:25:42

Sod of death? Well, that's when I need my colleague, Barry O'Reilly, who's material culture expert these days, but who did his thesis on the sod of death. I'm desperately trying to remember his conclusion, but it is published somewhere. So a different story, but another rich body of traditions about the idea being: really, who knows where we'll end up, but you know, if it's que sera sera, if you happen to be on the spot where you are destined to die, well, you'll die. And I don't remember his conclusion. So I can't tell you how many versions, but it's definitely over hundred versions in Ireland.

Kate Chadbourne 1:26:37

Well, I wanted to jump back in there because one of the versions of sgian an aghaidh na tuinne from the seanfhocail in Donegal actually ends in a funny way—just connecting with what you said. It's the shoe, the shoe, the knife version or one of them. And the last line is an interesting line. It says [IRISH PHRASE]. I can't remember if he called him [IRISH PHRASE] and he never again saw the man on the horse until the day of his death, which I really wondered about, of course, and then that implies that fishermen maybe are going somewhere different, right? Well, that's my dad. I don't know. Yeah, yeah. I love that you brought the death aspect in. We have sex, we have death, we… you know, rock and roll! [LAUGHS]

Audience 7 1:27:30

I understand that this is the first recorded film version of the Irish language spoken. But can you give us some idea of how many hours before this are there audio recordings of Irish being spoken? Is it a lot? Or was this groundbreaking in that way?

Deirdre Ní Chonghaile 1:27:53

I think Rudolf Trebitsch would be the first person to have recorded Irish, on probably the phonograph. He was a very wealthy Austrian, and in a very kind of 19th century sense, headed off to collect the sounds of the world. Even got as far as Greenland around the 1900s. And I think it's 1903 that he recorded in Dublin. And I think that's the first sound recording of the Irish language being spoken. Shortly thereafter, there's others. There’s Father Luke Donnellan. The collection is in the National Folklore Collection. And he actually was in the Aran Islands as well. It was only recently that I found that out. So I'm still putting in the hours of listening to clrrrrrg!, trying to figure out what's on them, which is a slow process. But yeah, as soon as the technology appears, it's not far behind that suddenly, the language appears on record as well.

Barbara Hillers 1:28:48

And I would like to mention also a little after the recordings Deidre mentioned, by a person with the surname of Dunne, but not our beloved Charles Dunne, who contributed the first sort of learning Irish by conversational pieces. So that's, I believe, 1913, if I remember. And that was on wax cylinders for Parlophone. And they were, for the longest time, still are part of the Milman Parry Collection of Oral Literature where they got through Dunne's involvement with the Milman Parry Collection. And they are now digitized, so you can actually listen to them now online, I believe.

Deirdre Ní Chonghaile 1:29:51

It just occurs to me that a question that came to mind somewhere along the journey from Connemara to here was: what was the next Irish language film made? And I could be wrong, but—all Irish language, we'll say—it might be Bob Quinn. It might be Poitín or one of those and that's, you know, 60s, 70s. So that really puts this into perspective.

Catherine McKenna 1:30:15

I was just thinking in response to the question about recording of Irish that it might be interesting to talk about the work of the Folklore of Ireland Society and [INAUDIBLE] folklore collecting and the use of the Ediphone cylinders and so on. [INAUDIBLE]

Barbara Hillers 1:30:39

Good point. Yes. So once Delargy got going on his collecting mission, he– Actually, another American connection: before he got the Irish government to fund his Irish Folklore Commission, when it was still the Irish Folklore Institute, he got a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation, and they equipped him with Ediphone machines. That's probably how he was introduced to it. So he had just one or two of these machines. And at that time, he was working with part-time collectors, people like Pádraig Mac Gréine. And Pádraig Mac Gréine described how they would get this Ediphone machine for just a couple of weeks. [LAUGHING] And then they had to get their people together and record the hell out of them! And then pass the Ediphone on. And once the Irish Folklore Commission got going, they had between five and nine full-time collectors in the field at any point, and other full-time collectors had an Epiphone machine. So once they had figured out how to work the machine—hairy stories about that—they would record, then transcribe, back at home, into notebooks, and send the notebooks and the cylinders to headquarters, then in Earlsfort Terrace, Stephen’s Green in Dublin, where they would be shaved down. So that's, of course, the tragedy, especially for song. But on the other hand, we have the best transcriptions of this material you could ever wish for, because they were all native speakers of the area where they recorded, they did it close to the event, they could go back and correct, and they clearly did; we know from the notes. So they've been transcribed. No one now could go back and transcribe all this material, and also as our sound archivist Anna Bale says, “People come in, and they are so excited. We have about a thousand of these wax cylinders left that were not recycled.” And so it's wonderful that they are there. But of course, the quality is, as you can imagine, pretty atrocious. And so she says people come in and are all so excited about these [LAUGHING] and then they listen to it! So I think much to be grateful for that we have these brilliant transcriptions.

Deirdre Ní Chonghaile 1:33:38

There's one thing I'll say about the experience of listening to those kinds of recordings. I've done the time, I've walked the walk. [LAUGHTER] Even if you can't always understand what they're saying, the magic never wears. The human voice really just transcends time and space for that instance. And I remember in my own notes, because my habit is I will listen to a recording and just literally just stream of consciousness write my impressions from listening to it because I find it helpful. And one man I named [IRISH PHRASE], the I-Don't-Like-Fireworks Man, because his style of performance was so fantastic. He clearly loved the experience of being recorded. And just he let it rip! every time he was being recorded. So sometimes even though the recording is really, really dodgy, this guy is irresistible, really.

Barbara Hillers 1:34:35

Yeah, they’re absolutely magic and partly because you actually realize that this is a long time ago. And so I encourage you to waste your precious time. So Google “the National Folklore Collection website,” or just Google “Béal Beo,” the living tradition, a light most alive. And they actually put some selection of these crackly Ediphones online so you can listen to them and catch the magic.

Audience 8 1:35:21

One of the things I'm struck by is the way that technology functioned back then versus today. We're so media saturated, and you know, we use technology as a means of communication and staying in touch with people around the world and whatnot. I'm struck by how when we examine some of these older films that four people in the world have seen, or even, say, silent films from the 1920s, about how modern some of the expressions are, and some of the ways of relating and telling the story. And I'm wondering, those of you who have spent a lot of time with this piece, if you have a similar reaction. Do you feel like you could walk down the street and the storyteller would be right there? Or is there a distance? Somewhat metaphysical question.

Natasha Sumner 1:36:23

I suppose there's that for me, with my folklore training, I look at this and go, “Okay, this is great. This is a representation of folklore.” And yet I see that it's a little bit staged. And so, for me, with my background, I kind of go “This is absolutely wonderful!” But yeah, I recognize that this isn't me literally stumbling into an actual event, though it's the closest thing that we're going to get to it, and it's very, very, very well done. So maybe I'm not the best person to ask. But what does everybody else think of this?

Maureen Foley 1:37:08

I was truly struck by how modern it felt cinematically. I was stunned by that. I mean, there are few little things, like the little boy seems to be facing Maggie and not the storyteller. Like there are little things that you would change if you were going to do everything perfectly. But in terms of understanding the emotional impact of the extreme-close-up and how you pace a film. I mean, the fact that we've just got a brief glimpse of the storyteller, and then we don't see him in a single shot again for another nine minutes. And so the editing that's involved in realizing that if, let's build up to the big moment where we finally see him, and it sort of provides a visual climax for the film. So I really was not prepared for the way it was shot and edited is pretty much how we do things today. And given the early nature of that film, it was very surprising to see.

Deirdre Ní Chonghaile 1:38:09

I'll just add as well, that my first time watching it, having grown up with Man of Aran, and my first time seeing Man of Aran was maybe as an eight-year-old brought in to sit on very hard chairs in [?Cill Rónáin?] in Aran probably some damp summer's night. And what I was struck by watching this was it just felt like someone had shouted, “That's a wrap!” on Man of Aran, and then you turned around, and there's the cast saying, “Now, we’ll get to being ourselves!” in a sense. Not that there wasn't kind of a sense of themselves in Man of Aran but Man of Aran is just so epic by comparison, and this so intimate, and Man of Aran is the island and the weather and the elements and struggle and all of that. This is just so human. And that because the people in it were able to communicate that. So that was my sense anyway; it was their own voices, just loud and clear, ringing almost.

Kate Chadbourne 1:39:13

I think what struck me too—I love that you had brought this up, Deirdre—is that the expressions on those faces are remarkably fresh and authentic. And it made me think about the way we hear and hear again. I mean, sure they probably heard that story a dozen times over those ten days. And yet those things are still so effective. And it made me think about being in Gleann Cholm Cille and listening to James Byrne play his party piece. Like, every night it would come up. And every night we would fall into hushed appreciation. You know, Eileen. We could never hear it enough. I mean, I wish we were hearing it now. You didn't have to stage that. You were thrilled to hear it again. And you heard something New in it every time.]

Unknown Speaker

Yes, yes, indeed. Yes!

[INAUDIBLE SECTION]

Kate Chadbourne 1:41:12

No, I think I've been lucky that people are always– Hannah and others who have studied here with me. I'm always for “Let's ask!” What we've heard from Barbara and from Deirdre and Maureen—well, from all of us—there's a hunger to share what we know is of value. And that's been what I've encountered every time like, “Oh, I want to share this.” And of course, I want to share the things that I've learned. So we're sending it on. I can understand that and there are a million stories right about singers who literally stop in mid-verse while somebody is going by the house. But I think those are just mean old, almost like YouTube stories—[LAUGHS] you know what I mean?—more than they are real because I think most of the real singers and storytellers would rather the thing go on and see it travel through beyond. What do you think yourself?

[INAUDIBLE AUDIENCE COMMENT]

Barbara Hillers 1:43:04

Right. You know, just the reference to Seán Ó hEochaidh who collected for the Irish Folklore Commission, and even beyond when the Irish Folklore Commission ceased to exist, was incorporated into University College Dublin, he continued to contribute. And his relationship to Anna Nic an Luain whose vast repertoire he recorded.

[INAUDIBLE COMMENT]

Yes.

[INAUDIBLE COMMENT]

Yeah. Good point. So, the Irish Folklore Commission never paid any of their informants. The collectors, of course, were paid. They were paid a pittance. And lived obviously… It was very hard working conditions. And even the staff in the Irish Folklore Commission in the headquarters in Dublin were really, hugely underpaid, but they all felt that they were contributing to this great mission and Delargy was nothing if not a man with a mission. [LAUGHING] The Blues Brothers, you know, a mission from God! And he managed to get that vision across. And clearly, people who contributed to that, the tens of thousands of informants, felt that they were contributing to this great collective collaborative venture. And, you know, thanks to that we have their voices now. So certainly in the working years of the Irish Folklore Commission, thank God, people really just gave generously

Natasha Sumner 1:45:00