Down Hear: The Films of Mike Henderson with introduction and post-screening discussion with Jeremy Rossen and Mike Henderson.

Transcript

John Quackenbush 0:00

April 22, 2017. The Harvard Film Archive screened works by Mike Henderson. This is the audio recording of the introduction and the Q&A that followed. Participating are Jeremy Rossen, HFA Assistant Curator, and filmmaker Mike Henderson.

Jeremy Rossen 0:20

Alright, good evening, ladies and gentlemen. Jeremy Rossen here from the Harvard Film Archive, and it's my pleasure and honor to be here tonight, to have Mike Henderson here in person. This is a program that's near and dear to my heart and one that I've been working on for a few years now. So it makes me very happy to be here tonight to be able to introduce Mike. But before I introduce Mike up here, I just wanted to give a brief background on Mike and his films ‘cause I feel like it's only recently Mike's pretty well-known as a painter and a blues musician, but his films are finally getting out there into the world. And so hopefully, you know, with more and more screenings like this, people will know about his films as well.

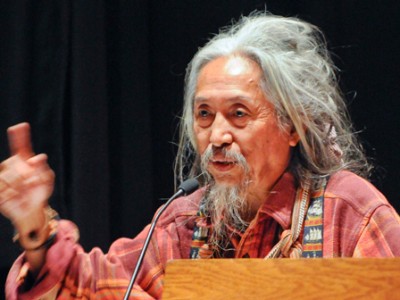

Mike was formally trained as a painter and a blues guitarist, and he expanded his creative expression in the 60s to filmmaking. Radical, innovative, political, and often comical, Henderson's 16 millimeter short works are an eccentric outgrowth of his music and painting backgrounds. Initially manifesting from a desire to animate the figures in his paintings, which he thought would give his artwork greater depth, Henderson's powerful candid work ranges from audiovisual composition experiments, to musings on creativity, to John Lee Hooker-style spoken blues performances about the Black experience and Black identity. As the late filmmaker and Mike's longtime friend and collaborator Robert Nelson has noted, “Henderson's movies are the first movies in the world to bring the authentic talking blues tradition into film.” Henderson's films typically address a variety of political and social issues, many times with wry humor, along with performative and introspective elements.

Born in Marshall, Missouri—who we were talking about that earlier, as is Mike Hutcherson, the photographer here—Mike headed to California after high school to attend the San Francisco Art Institute, the first and only racially integrated art school in the United States in the 60s. It was here that he fortuitously met teacher and filmmaker Robert Nelson, amongst others. The filmmaker Peter Hutton was in the Bay Area at that time as well. And Nelson would kind of teach Henderson the basics on how to shoot and edit 16 millimeter film.

A heated time to be an artist in San Francisco, the 60s politically activated Henderson. He was profoundly affected by the assassination of MLK and exposed him to a wide spectrum of artists, musicians and filmmakers. Mike Henderson eventually joined the faculty of UC Davis as a professor of art, teaching painting, drawing and filmmaking until his retirement in 2012 after forty-three years of teaching. Pretty spectacular.

So tonight, this is selection of all 16 millimeter shorts that have been preserved by Mark Toscano at the Academy Film Archive who has been working with Mike for the last several years to painstakingly restore all these all these 16 millimeter films, and there'll be more coming in the near future. And I'm happy to say too, Mike, now that he's retired, has got a Bolex and some film stock and so there'll be new films coming into the near future. So that's a very exciting thing to know. So, with that, though, I'll stop blabbing. And join me in welcoming Mike Henderson up to the podium, please.

[APPLAUSE]

Mike Henderson 4:14

Thank you.

[SCATTERED LAUGHTER]

Jeremy Rossen 4:20

We'll be around for a Q&A afterwards. So you could talk a little more in detail about what you're about to see right now.

Mike Henderson 4:33

I don't know what to say, except all of a sudden you're in a place like this, Harvard University. I feel like a little old country boy’s come a long ways. And I hope when you see the films, you have many questions because… the only thing I can really say is I enjoyed making films. I didn't intend to make films. But relating to what Mark was talking about when Dr. King was assassinated... I was working on a painting. I was always painting. I really didn't take any film classes. I had the urge to make a film because I wanted my figures in my paintings to move. After that, I came back, and we're going down to listen to all the speeches, walking back to the Art Institute, standing in front of my painting. And I said, “Ah god, it isn't enough!” you know, when you're that age, when you think that what you're gonna do is going to change the world or whatever, or wake people up or something. I thought that painting was all of that. And then, like I said, again, I decided that I want my figures to move, and how could I do that? And I thought about film. My first film was the one I made called The Last Supper. And that had to do with growing up as a Baptist, and later becoming Catholic, and so forth. And realizing that I thought that for me, as a kid, I always had these questions about life and growing up in Missouri, we were segregated, you know, and so forth. So you come to church, you see these idols in the church, and they all are Caucasian. And the same thing that is suppressing you are Caucasians, so it didn't make any sense. But it was something that you’re trained to ignore growing up. You're not supposed to ask that, you're not supposed to think that. So I wanted to make a movie about religion, because I thought it had been a major stumbling block with a lot of stuff that I felt about African American culture. So that was the first film I made. And then the second film I made was called Dufus, “he was a hardworking man.” [LAUGHS]

But anyway, I wanted to make a film. I love making films, but I hated waiting on everybody. You get a film together, to shoot the first film, you have to wait for this person, then I had to get this person and that person. I love filmmaking, but I want to find some way of dealing with this, that I continue doing, where I can just make the film without so many people. And I remember my first day at the Art Institute, the first week there or so, Bruce Nauman was teaching a class. And he made this film called Manipulating a Stretcher Bar. And I was just so outraged about it, because all he did was move it this way. He moved that way, and moved this way and moved it that way. And that was it. And he said “Any questions?” And somebody raised their hand and said, “Well, what does it mean?” He goes, “Nothing.” [LAUGHS] And that made more people mad. They said, “Well, why are we standing looking at it?” And he would say, “Well, you don't have to.” I mean, you know, being from Missouri, what did I know? So I just sort of took it all in. But what I remembered from that was just him and the camera. And I said “That's what I'm gonna [do], find a way of getting where it’s just me and the camera.” Like, it's when I painted, it's just me and the canvas. I have a relationship with the canvas, and the paint and the brush and so forth. And that's all I wanted. I didn't want anything in between this, like waiting for this person, waiting for that person or whatever. So later the films became with me in them and so forth. As you look at these films, like I said, you will see that in each film, I was trying to technically do something, you know, I was always trying to get the most perfect exposure... with bad eyes. [LAUGHS] I was always trying to keep the camera steady, shaking, something. There was always something, you know, but my intentions were to be a zenith point as much as possible. And the creative part comes in when you get rid of your preconceived ideas, which I knew about painting, because it's a relationship: the painting has an idea of what it wants to be, you have an idea of what you want to be, so it's like going out to dinner with someone you love or you’re married to and they want Mexican food, you want Chinese food, so you compromise. You get Italian, or something, you know.

And, I realized that when you got something that was in focus or out of focus, it’s shaky or whatever, you got to use what you got. And so the films are a combination of everything that I learned about creativity in myself. And my work is basically... I'm trying to figure out who the hell I am. And my work is about trying to figure that out, you know. Like I said, again, in the 60s, and all the artists, everybody's like, “Who are you?” “Well, I'm Mike Henderson.” “Well, that's what you’re told who you are, but who are you really?” And the arts are a wonderful way of finding out who you are. You know, there's a reason we all got a blind spot in the back of our heads; we can't see ourselves. We all want third eyes. We don't have them. So art is writing, dance—all these things—music and filmmaking, painting... All these things are a ways for us to learn about ourselves. It’s the most organic thing that we as humans can bring to this planet, as a tree brings fruit or something like that. And we bring our work. So with that, I'll let you look at the films and then ask any questions and so forth and I’ll see if I can find a way of squirming out of them [LAUGHS]... academically! [LAUGHS]

[APPLAUSE]

John Quackenbush 12:00

And now, Jeremy Rossen.

Jeremy Rossen 12:03

Another round of applause for Mike Henderson, now that he’s up here!

[APPLAUSE]

So, how are you feeling, Mike?

Mike Henderson

I’m feelin’ like a government check. I’m feelin’ good.

Jeremy Rossen

So there's a lot to unpack here with the films. But I think before we get into the films, and I think also, I think you have the best titles for all of your films too. The best title maker for films, but I just want to start again at the beginning, because I think your film work kind of maybe took a backseat for a while to your teaching career and your music career and your painting career. Now the films are being screened publicly again. So I wondered, what do you think about that now, you know, seeing these films now?

Mike Henderson 13:20

You know, I never think about it. I always feel like—not to be arrogant or anything—I always feel like artists should not be looking for immediate gratification. You know, if you're that well understood or that well... Art should have some mystery. Like the Mona Lisa, everybody goes to wonder what's the smile about or something. That whole thing when the painting went on an exhibit, there were more people who came to see the place where the painting had hung, than had been there to see the painting itself. There’s something about when things become– As an artist, you do the work, and it isn't for yourself. It comes through you; you don't own it. And when it comes to be accepted, it’s because you're not doing something that has a market; you're like a leaf that falls from a tree. Now what purpose does that have, you know? But it's very essential. It's a question that a lot of people get concerned [about]: “Well, if my work isn’t showing or it's not selling, then I'm not gonna do it.” I'm not like that. I never had those aspirations of wanting money or achieving money. There was something else I was always after. I don't know what it is. Like I said, I make this work to try to find out who the hell I am, and what is my purpose in life and this stuff. I remember reading this– Well, I didn't read it, I should tell you the truth. I had a hippie girlfriend in the 60s, and we would go to [UNKNOWN] during New Year’s. And one New Year’s, she read this book called Beginner's Mind, Zen Mind. And there was one phrase in this book that just... I said, “That's gonna be my life,” and it was: “Lay back and enjoy the ride. Don't worry about where the tracks are going.” And so making work is that way for me, you know, sometimes you just gotta chop and not worry about where the pieces fall. Will it be seen? That’s why I say, again, I never really tried to get the work out. I did put it in Canyon Cinema. I did have a friend who worked there. She was in some of my films. She would always make sure I got one rental a year. And then when they closed, you know, I just made films and stuck them on the shelf. You know, I didn't worry about Was it going to be shown? Because all my heroes died poor; they died struggling. Van Gogh, you name them all, you know, some of them never sold a painting in their lifetime. And these people were big influences on me, so why should I feel that I should want more than they had? You know, that whole thing: do you take more than you give or do you give more than you take? Or whatever.

Well you can see, I had a lot of conflict growing up as a kid, especially at home, trying to explain these ideas to my parents and other people around me. But I did find people who encouraged me to do what I do. And I just sort of stuck with my guns of, “Well, I don't know why I do it.” God knows, my next lifetime, I'm gonna be a lawyer! [LAUGHS] I'll come here and go to school! So, I don't know, I realize it's a gift, and I don't own it, and it comes up through you. My work doesn't come from my head; I feel it and it comes through me and I do it. I don't feel like I own it. You know, like the apple tree that grows the apples, you don't own the apples, they just come out of there. And I think sometimes as people do—because you know, dogs and cats don't worry about these things, but we do. They just live until they die. We worry about what we're going to leave and who's going to have it and this and that and so forth. They just live until they die and they go along with what they do.

And so with that in mind, I just sort of like... When I would spend my last buck for a tube of paint instead of food, or hear my girlfriend say, “I'm not gonna spend another night here watching you paint!” [LAUGHS] And she walks out the door. You give up the relationship, you know, I don't know why you do it. That's what you feel, and that's what you do. Those are prices you pay and I never looked back. I just love making films. I don't have any answers; they all are questions about like I said, who I am, what my purpose is, and so forth. And like I said, again, that's the reason why we don't have eyes on the back of our head; we all got a blind spot. And it's great when work does get seen, and I do appreciate all that. And I'm not one of these people who I'd rather die in obscurity either. I'm not one of those either, you know, I just sort of stay in the studio do the work. Focus on that. I never really thought about it... Sort of like wine, it ages. They had to age, you know. I mean, when I first started making films, nobody wanted to see them, you know, so forth. It didn't bother me. I just wanted to make them, so I never really let that deter me or enter in my thinking. Sometimes it's more of a struggle when you sell something or you get accepted, then: “Well, uh-oh, should I make the same thing again? Is that what's going to do it?” or this or that, and so forth? We all have different roles to play in life, and I just learned accepting what mine is, as an artist. And the greatest feeling that you can have as an artist that your work inspires other people to become artists. They say, “Well, I can do that!” whatever, you know. And you want to give back as much as you take in. I never met Van Gogh, but Jesus, man—I've never met Fellini either—but just seeing those things he did inspired me, just how he can fill a frame like a photographer, and keep going, man.

Jeremy Rossen 21:26

And I feel like as a teacher for forty-three years, you must have inspired several generations of artists and filmmakers over the years as well. But I wondered if you could talk a little bit about the film Down Hear, because I feel like that one in particular for me, when I first saw it... It’s a very haunting film that kind of stayed with me. And it stayed with me when Mark Toscano showed it to me. Every time I see it, it's just this powerful haunting piece. And I heard a little bit of backstory in that how you made it with your brother Raymond who was kind of in trouble at the time, and–

Mike Henderson

Always in trouble! [LAUGHS]

Jeremy Rossen

Yeah, I have a brother like that too. But, I wondered if you could talk a little bit about the experience of making Down Hear with your brother...

Mike Henderson 22:23

Yeah, at the time, I lived in San Francisco, and I got this apartment. It was a great landlord, Chapelone. Anyway, across the street was the projects. And every Saturday, I'd see the guys in the projects, you know, the police come in search ‘em and they go through this routine. Still living in the projects with their moms and so forth, and having kids and so forth. I kept watching this routine. And I remember I had just bought a tape recorder, a sound-on-sound recorder. And I was sitting there looking out the window. I was practicing the guitar playing with the tape recorder. And all of a sudden the song came to me about what I was seeing. And that song was the first song I ever did where the images came to me and I knew what the film was gonna look like. And back to my hippie girlfriend... She was a dancer. And she would take me to all these dance concerts, modern dance things, you know, and I would go, and I remember seeing this one with Merce Cunningham who was my favorite dancer because he was big and clumsy like myself. He did this dance called “Non-movement'' where he just laid on the floor, and his other dancers were just flying around him jumping and flying through the air so gracefully. And I just, hmmm, I thought about that. So the format, I thought it was going to be like a performance. You know, I was going to leave everything in the film. I put the camera on a tripod, of course the Bolex. When I would go out of the frame, I was going to rewind the camera each time to shoot, so I left all of that in there. I wanted it to be, sort of, as real and as raw as possible. And then I, like I said, again, got him, and I sort of went back to the tape where this song had came to me as I was looking out the window. I'm going through all of this, looking at what I was seeing, trying to process it in some sort of way. It's just something takes over you, sort of comes out of you. And I went and got choices from the song to use to narrate it after I shot it, but I knew what everything was going to look like, basically and shot it in the house. Like I said, again, it was one of those films that I was dearly set on trying to make a film where I didn't have to depend on anybody. I knew I could get a couple quarts of beer, give my brother some money, and he would stay as long as the beer was there. And that was about it, but the whole idea of film came from watching these guys just go into the same old routines. And it was very interesting, because this came back later when I recorded a CD called Trouble Ain’t No Stranger. It was my last CD. And this whole song came back.

The first time I went to Europe, I was looking out the window and I'm flying over the ocean, you see all this. I was going to Europe to play, and I hadn’t been there before. And I started thinking about all the wars that have been fought on this ocean and ships and lives have been lost into it and all of this stuff. And I look down and I see this slave ship headed towards the States. And I see this one guy who looks up at me. And he says to me, like, “Don't worry, I've gone through this, so you can go over there and have fun. You won't be like a father carrying a rifle over there. You’re carrying a guitar; you're going to have fun, and you're going to be appreciated,” and all this stuff. “That's why I suffered for all this, so don't feel negative and question yourself: ‘Why me? Why am I doing this? Why am I going?’ Just go do it.” And this whole movie Down Hear came back to me again. I was one of those things, like I was glad I made it, you know. And later, like I said, again, this issue came up when I got back and I recorded the rest of the song and put some changes to it, and that’s on my CD. But yeah, that movie, too, was one that I felt was... Every time I see it, I'm glad I made it. Maybe it says something about me or how I feel or whatever. It was like the painting I saw, Van Gogh’s Potato Eaters just slapped me across the face. I realized that Black people weren't the only people that suffered in this world. When I saw The Potato Eaters, and you look at that painting, and you see how crudely these forks are in the faces of these people, in this dim light and all of this stuff. And there's this part of you that wants to, as an artist, be a voice for all of those people who don't paint or don't make films or don't sing, you know? Same way when I go to the doctor, I want that doctor to be well-versed in what he does, a voice for that. I wanted to be the voice for the voiceless. I felt it was my duty as an artist. I guess that's one of the reasons why too, that that's something that stuck with me when I got to art school when I was taught that, as an artist, your responsibility is to the people who don't paint, because we create and people that create, you don't own it; it comes through you. And it's all the other things that goes in the world around you that gives you the motivation for doing what you're doing. Your job is to do it. Your job is not to sell it or prostitute it or whatever. How to get the next nickel out of it. That I did try to teach to my students, so I used to say to them, “If you become an artist or whatever, art will show you... You'll be a better parent, because you realize there's more than one way to do stuff. Maybe you take an art course, and just walk around the room and look at all the work. And you see everybody's got a different way of looking at whatever's in front of them, you know?”

And it's one thing to talk about it. The other thing is to put it in practice. And I really wanted to put all of those things in practice, you know? So like I said, again, yeah, I feel something too each time I see that film, I feel like, that's why I put the beginning on, what I say what I said about you know, “This film is for Black youth” and blah, blah, blah, because I would watch this and I’d see these kids just go through the same old moves all the time, and it just gets boring after a while. Just take responsibility for yourself, you know, don't let the world take responsibility for you, and so forth.

And the next film that was a change was when I made Pitchfork and the Devil. The filmmaker in me, you know, that still comes around too, like, “Mike, you never done any of the dang sync sound!” And you know, you want to cross all the bridges that are possible, so I wanted to shoot something sync sound, I wanted to work with people again, and so forth. So that film was done that way. That's the reason why I shot that, and the main character—that guy who's at the end, DeWitt—I met him, and when I was going to school, I would work in these programs the government had put together to keep kids off the street. And DeWitt was one of those kids who was troubled all the time. And when the program was over, for some reason, he just kept hanging around my knee and so forth. So I figured I'd get rid of him if I gave him something to do. And that damn near drove me crazy. This guy would come over to my house. And sometimes I would go to bed, and he would still be on the phone with his girlfriend Kool-Aid who I never met. I never met her. All I know it was Kool-Aid. “I love that woman, man, Kool-Aid!” And he ended up a tragic death, but he wanted to be in a movie. He said, “I want to be a player, I want to be a player.” And I said, “Dude, what are you gonna do with your life?” “You're gonna make a movie, I'm gonna be a star.” “Nobody's gonna see this movie. Probably not even me!” So anybody who was staying around me that long, I just said, “Okay, I got to put them in movies.” And then I started making movies when anybody would come by my house, you know, I’d pull out the camera, and they either would stay or leave!

And I don't know, what's the other one? How to Beat a Dead Horse. The guy who was moving the movie light, he was a taxi driver. He would stop by on his break. You know, these guys would interrupt me from painting. So I always had film, just like I said, like I [had] paint, I’d have a camera. And then the idea would come to me and I'd say, okay, boom, and I’d get the camera—it was always loaded—and I’d just set it up on the tripod and think of something to do with them.

Jeremy Rossen 34:13

Maybe we'll take a couple questions from the audience here, before we get to more questions... So right over there. If you wait for the microphone, please, thank you.

Audience 1 34:25

I have two questions. One of them is, I think, a hard question. You say that your films start with a question. Can you–?

Mike Henderson 34:41

Oh, when I'm making a film, they’re like questions to find out who I am. That’s why I say I make them that way.

Audience 1 34:52

Okay, then I'll ask the second question. Can you think of any questions specifically that you have asked, that you’ve investigated, in the sense these are investigations?

Mike Henderson 35:06

Yeah, religion, The Last Supper one. Christianity, you know, like I said, again, it sort of demonized everything African American stood for in terms of ideas about music. “It's the devil's music. It's this, it’s that,” so forth. What other one? Down Hear, that was another one…

Audience 1

And the question there…?

Mike Henderson

Was the repetition of Black youth falling into this dark hole of being–

Audience 1

[INAUDIBLE]

Mike Henderson

Yeah, living in the projects, going through the same ol’ moves and so forth and all this.

Audience 1 35:49

Right. I think a film that interests me was the one where you do that reverse pullback, like watching something, we’re seeing the lights–

Mike Henderson 36:03

Oh, yeah, Too Late to Stop Down Now, yeah.

Audience 1 36:07

Right. I happened to have loved that. What do you think the question was?

Mike Henderson 36:16

Oh, the question had to do with this idea—it will come up again, tomorrow, when they show King David—was that I had this idea at one point, that if I set up the camera, the action will find the camera; I don't have to go looking for it. So the whole thing was, I was in my painting studio, and I said, “The film is here. Can I find it?” So there was the–

Audience 1

[LAUGHS] That’s the question.

Mike Henderson

Yeah, yeah, you know, “Can you find it in front of you? Do you need all of this stuff to make a film? Can you just find the film in front of you?” And I will say this. I have used that question– Me and Bob Nelson, one time we went out with 35 millimeter cameras, and we would pick a spot, and we’d say, “Okay, I'm going to photograph this six feet, and I'm going to shoot a 36 roll of film, and I'm going to find the interesting frame there,” which I always called it “eye-training” and so forth. We were just gonna photograph this and find the interesting... something in this floor that's going to make me feel like I'm inspired, like I haven't wasted my time or whatever. To see—I don't know—just that, you know.

Audience 1

[INAUDIBLE]

Mike Henderson

Yeah. And when I was using the camera, which I still do, I always feel like it's like eye training, like, you know, if you're running a race, you're going to train your muscle. You’re training your eye to see the quintessence of the minimalists or something... or nothing, you know. Trying to hone it down to... Like I was saying Fellini could fill a frame, like it's a painting. And there's lots of frames in his films, you know! Kurosawa was another one. They can hold you there with one frame if they wanted to. So, eye training, I guess that's what the question was about, you know, “Can I find this film here? Can I find a film with just me and my camera and so forth?”

Jeremy Rossen 39:07

We’ve got another question down here.

Mike Henderson 39:10

Down Hear.

[JEREMY LAUGHS]

[INAUDIBLE AUDIENCE QUESTION]

Mike Henderson 39:18

No, and now, I'll never know. But that's the fun of the chase, you know, reaching for something, the unattainable goal. And it's something that intrigues me as an artist just because it's there, you know. It makes no sense, but, you know, art’s not supposed to make sense. [LAUGHS] It’s supposed to make artists! [LAUGHS]

Jeremy Rossen 40:06

Other questions out there? Wait for the microphone.

Audience 1 40:15

I'm gonna ask my second question, which is about Robert Nelson. You’ll probably speak about him tomorrow, but since he came up... I think he had a quote that “If you're not having fun, you're not making art.” Something like that.

Mike Henderson 40:34

I could believe Bob said that, and if he didn’t say it, I will attribute it to him anyway, because he was that way. That's why we hit it off right away when I met him. I met him through an accident. And I was coming to the school one morning. And I was riding the cable car. That was one of the great things about living in San Francisco. So beautiful coming over the hills to North Beach. I lived in the Mission. And a truck backs into the cable car and knocks me off. They took me to the hospital and said, “Who should we call?” And I said “The Art Institute.” They sent over one of the trustees who looked like he was a lawyer for, I don't know, God or somebody. They thought I was a king or something when he arrived at the hospital. [LAUGHS] Anyway, he says, “Don't worry about a thing.” The next day calls me and says, “I got a check for you for two grand.” So I said, “Okay.” So I go down to the Bank of America building, walk across this deep carpet to get to check. And I had to write a paper for an art history class. And I’m wondering “How can I do this?” I haven't figured out how to cheat yet. But I was trying to figure out something. Okay, the thing to do is to find the guy who made the sculpture that I'm going to write about and ask him “What was it all about?” And how did he make it and so forth and I get a passing grade in the class, and I can go back to my painting. So the guy who I thought was Robert Hudson, turned out to be Robert Nelson! And I said, “Well, what do you do?” He says, “I make films. I teach filmmaking here.” And I said, “I want to make a film.” And I swear to God, at this moment, this woman comes up and says, “Bob, you know anybody who wants to buy a 16 millimeter Bolex?” And he said, “He does!” So being the rich man I was, I pulled out two hundred dollars and gave it to her, bought the camera. And he says, “You really gonna do it? Make a film?” He says, “Take a film class?” I said, “No, I don’t wanna take no film classes. I want to make the film!” So he says, Well, if you want to, show up this time,next week. There's a lab at the bottom of the hill where you can buy film. I'll show you how to load the camera.” So I went there, and I bought like three or four rows of black and white film. And he showed me how to load the camera. I get my buddies together. We shoot this thing. And next week, when he comes back in, I said “I got the film.” Before class, he shows up, splices it all together, put it up, and I loaded the camera wrong. The film’s going bublbulbublbubl…fluttering. [LAUGHTER] So he's trying to say, “Well, I think maybe you can cut some of this….” And I said, “No, I'm gonna do the whole thing over in color.” He said, “You are?” I said “Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah!” I said, “This camera, man, you look through it.. because you gotta use the viewfinder. You got to look…” And I said, “Is there a camera you can buy where you…” “Oh,” he says “Reflex.” So I had the money. I go to the camera store, spend the money on a reflex camera. I should have bought some more shoes [LAUGHS] and clothing, but I didn't. I bought the camera, and I got my buddies and some of the teachers at the school to be in the film. And I was a janitor at the school and making money too, and I was playing in a band back in those days. I was also the TA for the art history class which was in their library, so I asked the chair of the department, “Could I shoot this film in the library?” I just moved everything over, and so forth. And just shot the film and that was it. And he said, “Well, you oughta take a film class.” I said, “No, I’m not ready to take a film class. I just paint.” So I made Dufus, the second film, just you know, sitting there talking about buddies, about something. Anyway, then after that, he says, “We'll have a film show together.” I think he showed Bleu Shut and I showed The Last Supper. And then he says, “Well, you ought to take a film class and take more classes.” So anyway, I figured out if I get into the graduate film program, I could graduate in four years with a master's and a bachelor's degree. And I did. That was my challenge to see if I could get both degrees in four years. And I did and got hired at Davis and so forth.

Jeremy Rossen 46:07

But, your friendship with Robert Nelson turned out to be a lifelong friendship and a collaboration. You guys collaborate on many things together as well. So I wondered if you could talk a little bit about that, and that'll lead into tomorrow's screening, which is tomorrow at seven o'clock. Mike will be showing King David, which he made with Robert Nelson, which is a short, and then we'll show two of Robert Nelson's rarely seen, I think, masterworks, Suite California, Part One and Two. But yeah, if you could talk a little bit...

Mike Henderson 46:38

Oh yeah. I'm in both of those films.

Jeremy Rossen 46:41

Exactly.

Mike Henderson 46:42

Bob had gotten a Guggenheim and bought his Eclair camera and you could shoot all these different ways. You could shoot through the viewfinder and everything. So anyway, he was telling me about it. And I said, “Wow, that's incredible!” you know, so forth. And anyways, I said, “Bob, let's go shoot something.” And he says, “Okay. What shall we do?” And I said, it was that whole idea I'd had earlier, I got from painting, but didn't formalize it until later, like, set up the camera someplace, and the action we’ll find. So we figured out, we’d flip a coin, he pick a place. Or I would pick the place. If he picked the place, then I would do the first shot or whatever. So I've flipped and won. I said, “I'll go out to the ocean.” He says, “I don't know about that.” “Okay, where would you go?” He said, “There's this place called South Park in San Francisco.” And I said, “I don't know it. Let's go!” So that meant that I would get the first shot, I’d get to pick it. So anyway, we got a blanket and beer and salami and cheese and bread. And I just said, “Okay, we'll just sit here till we find something.” So that's how that began.

And then we made several other films together and so forth. It was funny working with him, because I had this admiration for him up here, you know. My favorite film by him was Plastic Haircuts. Anyway, one time we were editing, and the film starts falling on the floor. So I see it, but I'm afraid to say something because, you know, Bob was a teacher, and he knows more about this stuff than I do. So I’m sort of like afraid to say, “Bob…” Maybe it should be on the floor? I don't know. So we started working on a soundtrack and we're making noise, pounding stuff, recording different things. And all of a sudden, the door opens. And it's his dad who was living in his house, very elderly. “Oh, Bob's dad! Wow, this is incredible, man. This is amazing, man. I wonder what he’s gonna say, you know. ‘You guys working on the film? What are you doing…?’” or this. He says, “Stop this damn noise, else I'm going on the county!” [LAUGHS]

We felt like two boys: “You go upstairs, and you go home! Wreckin’ my sleep! I'm trying to sleep here!” Bob's going, “Okay, Dad. Okay, Dad.” And I said, “Bob, by the way, the film's on the floor.” [LAUGHS] And I went out the door. It was always fun. It was always fun working with him. And like you said, if you weren't having fun, then it wasn't there. I felt that too, you know, if you're not enjoying what you're doing, don't get yourself in those predicaments. There's enough of that in life that happens to you naturally. Your body does that to you, so you don't have to worry about doing it yourself. But if you can find something that you love doing, do it, and like I said, again, if you haven't, take an art class. Art will always give you something to feed the soul. Maybe you'll be more tolerant, maybe you'll be a collector, maybe you'll be a sponsor or whatever. Maybe just another person that enjoys artists. Maybe your kids will be artists, and you could be the one, the aunt that says, “Okay, you don't have to be the doctor, you don’t have to be the lawyer, you know, you can go to art school.”

But like I said, again, Nelson was... When he moved to Minneapolis, I felt like I lost my right arm because I could call him anytime. I’d say, “Bob, we got a roll of film, let's go shoot something.” And he'd come over, and we would shoot something. Sometimes they turn out to be nothin’. Sometimes they turn out to be something that would become a film. We shot a lot of stuff that just I don't know what happened to. Maybe we just threw it away or whatever, because it was about shooting the film. And if there was something there, we put it together. And if it wasn't, we just tossed it. You know, so yeah, I've always said Bob was my teacher. And he would always go, “Of everything?” And I’d say, “Yeah.” [LAUGHS]

Jeremy Rossen 52:03

But Bob Nelson later on would go on to re-edit and rework some of his films, but you've never done that–

Unknown Speaker 52:11

Only with paintings! Yes I have. Yes I have. I've looked at it, and I've said, “What the hell was I thinking? That's too long.” To me, I never liked long films. I always felt like if you were experimental films, to take up my time, my precious time on this planet—’cause I don’t know how much I got—five minutes, I could give you. Ten minutes, yeah. But you know, you had to be, I don't know, Humphrey Bogart to keep me around for an hour or so, you know.

Jeremy Rossen 52:55

And so for your new films, do you have plans or ideas of things you want to work on? Are you kind of working as it–?

Mike Henderson 53:02

I’m one of those people who feel you if talk about what you’re gonna do, you'll never do it. So you’re filming, never talk about it. You know, every film I've talked about, never did. I always figured it’s like Duchamp: conceiving of an idea is just as valid as doing it. So when you conceive of that film, you've done it. There's no need to shoot it. Unless you want somebody to see it. Why do you want somebody to see it? You know, that’s the question: Why do you want somebody to see this?

Jeremy Rossen 53:35

Do we have any other questions in the audience here?

Mike Henderson 53:41

Nothing about my sex life?

[LAUGHTER]

Jeremy Rossen 53:45

That's afterhours.

[LAUGHTER]

So, join me in thanking Mike Henderson here tonight. And please come back tomorrow for the screening at 7pm. So thank you for coming out.

[APPLAUSE]

©Harvard Film Archive

Related film series

Explore more conversations

Kidlat Tahimik

Susumu Hani

Nathaniel Dorsky

Carter Eckert