The Last Days of Pompeii (Gli ultimi giorni di Pompei) introduction by Adrian Staehli.

Transcript

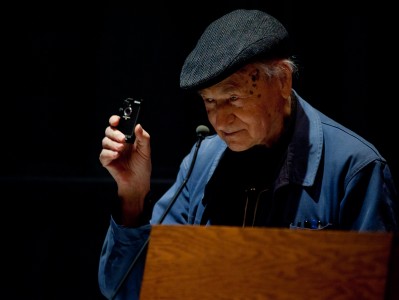

Adrian Staehli 0:00

[INITIAL AUDIO MISSING] begin with my very short speech. I'm Adrian Staehli. I'm very happy to introduce you in this 1926 silent movie, Gli ultimi giorni di Pompei, The Last Days of Pompeii, directed by Carmine Gallone and Amleto Palermi. Indeed, a landmark of early Italian film history, which you will see in a very rare print owned by the British Film Institute. I don't think that there are more than three prints existing, and none of them is complete. Gli ultimi giorni di Pompei, The Last Days of Pompeii, is staging, of course, the destruction of Pompeii through the historic eruption of Mount Vesuvius in August 79 A.D. The film's narrative is based on Edward Bulwer-Lytton's novel, The Last Days of Pompeii, from 1834, the most popular of all 19th-century historical novels, which had become the canonic narrative of Pompeii's extinction. Gallone’s and Palermi's film is not the first film about this subject. The destiny of the doomed city, spectacularly buried under the ashes of Mount Vesuvius, has long been a favorite subject of historical films set in Roman antiquity. Since Luigi Maggi's seminal film with the same title of 1908, there were in 1913 two other versions, both of them again produced in Italy and basing their screenplay on Bulwer-Lytton's novel. All of these versions were huge box office successes in Italy as well as abroad. With their astonishing visual effects and the grandeur of their mise-en-scène, they were at the forefront of cinematic innovation, and with a complex cinematic narrative paved the way for full-length movies. The Last Days of 1926, the one which we'll see shortly by Gallone and Palermi, is the result of a huge crisis in Italian film production. After World War One, Italy had lost its leading position in the main international film market, and had also fallen behind Germany and America in terms of technical and aesthetic innovations. Italian film companies strived to regain their foreign reputation by building on the past achievements of the Gilded Age of Italian cinema, the 1910s, with the production of lavish, extremely expensive historical movies set in Roman antiquity. But the relaunches of former box-office successes such as Quo Vadis? in 1924 proved to be highly uninspired and anachronistic symptoms of the industry's artistic and technical stagnation. These films could no longer compete with the vivid, expressive acting and dynamic film cutting of American productions like Fred Niblo's Ben-Hur of 1925. Gallone’s and Palermi's Gli ultimi giorni di Pompei was the last major effort to salvage Italian cinema. With its play time of more than three hours (this version here will be, this print here is quite shorter than three hours, but its play time was then three hours) and a total of 1400 takes -- many of them tinted, you will see that -- it was not only one of the longest and most lavish but also one of the most expensive Italian movies realized to date. Despite such enormous investments in Italian film production, the Unione Cinematografica Italiana, the large consortium of almost all major Italian film companies, went bankrupt in 1926. The worldwide distribution network of Italian films collapsed, American productions overtook the Italian domestic markets. Italian film companies were afterwards merged, nationalized, and became eventually, under the name of the Istituto Luce, a state firm, serving the aims of the visual mass propaganda of the Fascist regime.

The most impressive feature of Gli ultimi giorni di Pompei is certainly the elaborate and detailed richness and variety of its imagery, suggesting, in many instances, authenticity in the representation of ancient Roman buildings and costumes. The set decorations display sumptuous architectural settings, as well as luxurious interiors of Pompeii and houses adorned with wall paintings and furniture and crowded with life-size sculptures. Much of this was based on archaeological evidence from Roman times and even the excavations of Pompeii itself. But in many cases, the visual templates of representing antiquity used for this film are rooted in the visual culture of the 19th century. Nineteenth-century paintings depicting gladiatorial combats, chariot races, banquets, or just street scenes, or scenes of domestic life in Pompeian interiors, were extremely popular and circulated through engravings, photographs, and advertisements in newspapers and journals. Films of the silent movie era made abundant and often explicit use of such reenactments of 19th-century pictures, and Gallone’s and Palermi's Last Days is particularly packed with such references. The movie is further enriched by a good deal of female nudity and several bathing scenes. The film therefore appeals to spectators with overwhelming visual and voyeuristic pleasures. Its voyeurism was, however, criticized in many Italian newspapers as pagan decadence. Even worse, the film did not achieve the international box office success the producers had hoped for and failed to reach its goal. It could not salvage the Italian film industry. Not surprisingly, it was therefore the last epic in Roman antiquity produced during the Fascist era, with the sole exception of Scipio Africanus in 1937, a propaganda movie glorifying Mussolini's colonial wars in Africa. Let me add a few words about the production staff and the cast of the movie. The director, Carmine Gallone, became with this film a specialist for historic films, and was in 1937 assigned by Mussolini to direct Scipio Africanus. After the Second World War, he returned to epic films with Messalina and Carthage in Flames. For Amleto Palermi -- so, he became a specialist, apparently, for firework attractions. For Amleto Palermi, on the other hand, like Gallone, a well-known director of Italian comedies in the pre-war period, The Last Days was the only epic he ever made. The cast of the film is quite remarkable. Victor Varconi is the male lead. Born as Mihály Várkonyi in Hungarian, he plays Glaucus in this movie, was a Hungarian actor making his career as a film actor, mainly in German movies, and, since the mid-20s, in Hollywood, where he starred in several movies directed by Cecil B. DeMille, most notably as Pontius Pilate in The King of Kings in 1927. Beside Glaucus in The Last Days of Pompeii, the major lead he played was Lord Nelson in The Divine Lady of 1929, opposite Oscar-nominated Corrine Griffith as Lady Emma Hamilton. Again, a movie about a Vesuvian topic. The female lead is Rina De Liguoro, one of the big stars of Italian silent movies, becoming famous as the lead in Messalina in 1923, and playing Eunice in Quo Vadis? of 1925. Both films were major Italian productions set in Roman antiquity, and like The Last Days, intended to save Italian cinema. She played, by the way, her last minor role in the early 1960s, in Visconti's Gattopardo, The Leopard, co-starring with Burt Lancaster, Alain Delon, and Claudia Cardinale.

Other famous actors in The Last Days include the Hungarian María Corda and the German Bernhard Goetzke as Arbaces, the villain in the movie, who was known from Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler, Dr. Mabuse, the Player, and was starring in many German epics of the period. Finally, to conclude, I would like to thank all of who, all who made this screening possible. Brittany Gravely, David Pendleton, back there. Mark Johnson and Haden Guest from the Harvard Film Archive, the British Film Institute, which generously allowed us to borrow its unique print of the film. And last but not least, Susanne Ebbinghaus, the Curator of Ancient Art at the Harvard Art Museums, who had the initial idea for this evening's program, and also provided generous fundings from the Leventritt Fund that made this screening possible, and also, which is also the reason that you didn't pay any entry. Finally, I would like to thank our pianist who will accompany Gli ultimi giorni this evening. Please join me in giving a very warm welcome to Robert Humphreville.

[APPLAUSE]

© Harvard Film Archive

Explore more conversations

Jerry Schatzberg

Daniel Hui

Jonas Mekas

João Pedro Rodrigues & João Rui Guerra da Mata