The Deep Blue Sea introduction and post-screening discussion with David Pendleton and Terence Davies.

Transcript

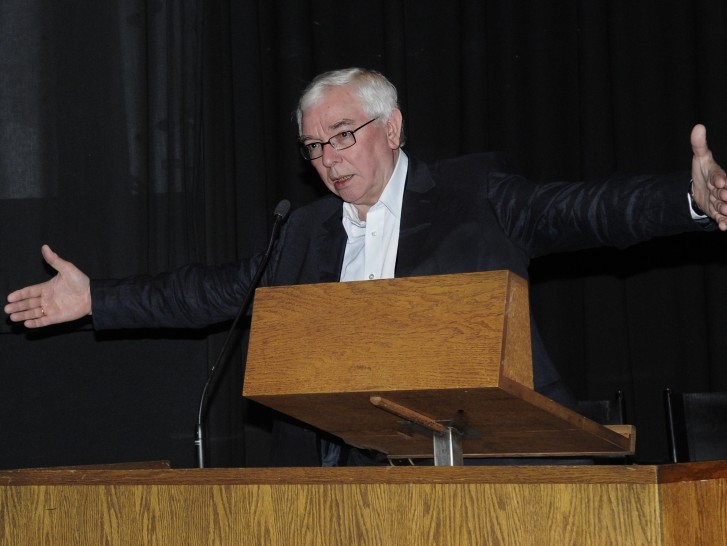

David Pendleton 0:01

Good evening, ladies and gentlemen. Thank you all for coming. My name is David Pendleton. I'm the programmer here at the Harvard Film Archive, and I'm terribly excited to be presenting to all of you the new film, The Deep Blue Sea, and its filmmaker Terence Davies, here tonight. I just have a couple of brief announcements to make and a brief introduction of the film itself. First of all, if you have anything on you that makes any noise or sheds any light, could you please turn it off and make sure that you leave it off until you exit the theater at the very end.

Our guest tonight, Terence Davies, leapt into prominence with his very first films made in the 1980s, a trilogy of black and white short films imagining the life of a gay man born in postwar England, and going from his birth to his death, beginning in the past and ending in the future. One could be forgiven for thinking that these films—which came to be known collectively as the Terence Davies Trilogy—were semi-autobiographical, since like their protagonist ,Davies himself was born just after the war into a working-class family in Liverpool. His first two feature films, Distant Voices, Still Lives from 1988 and The Long Day Closes from 1992, famously explored much the same territory, but in increasing detail and with increasing depth, complexity and subtlety. He branched out with his next two films, which were adaptations of American novels. First The Neon Bible from 1985 from the novel by John Kennedy Toole, and The House of Mirth from 2000, based of course on the Edith Wharton novel. His following project marked a return to his home territory of Liverpool. It was the documentary Of Time and the City from 2008, a valentine to his hometown made up largely of archival footage. And finally, the film that we're here to see tonight, The Deep Blue Sea, which unites many of the major strands in Davies' work. Like his previous two fiction films, this is an adaptation, in this case, of a play, the 1952 play by Terence Rattigan, who's generally considered the most important English playwright in the postwar era until the rise of the so-called angry young men. Rattigan’s play, like the film itself, is a melodramatic exploration of a love triangle between a wealthy judge, his younger wife and her even younger lover. And I hope that you won't think I'm being disparaging by using the word melodramatic, which is often used pejoratively today. But there was a time when melodrama accounted for much of the most incisive and insightful filmmaking, particularly in the Anglophone world, particularly in the 20th century. And it seems to me that Davies’ work harkens back unabashedly to that cinema, and particularly the postwar films of Douglas Sirk, David Lean and Vincent Minnelli.

This film, like The House of Mirth, is on fertile ground for melodrama. It's about a woman's life and death struggle to act on her desires in the face of overwhelming social pressure not to. The other thing that links it to David's earlier films—and if you look at the etymology of the word melodrama, it has to do with drama accompanied by music, and in fact, Davies is a master at setting images to music and orchestrating the whole, giving the images themselves an emotional intensity that's absolutely operatic, and again, hence the importance of music. The film also marks a return to postwar England, where Davies’ first films were set. And that's why the other films in this program that we're showing next weekend will be his first three feature films, those made in and those made about postwar England.

But above all, The Deep Blue Sea confirms Davies as unsurpassed, I believe, among living filmmakers anywhere in the world as a visual storyteller. Even adapting novels and now a play, Davies finds ways to tell his stories cinematically. He leaps forward and backward in time, turning the narrative into a kind of associative chain of episodes that operates very much like memory. And he's a brilliant orchestrator of color, camera movement, decor and lighting. You'll see the cinematography in this film is exquisite and very dark and moody. And I think the darkness provides a sort of a rich loamy ground from which these moments of emotional intensity flash forth, both on the soundtrack and on the faces of the film's actors.

The film is being distributed by Music Box Films and will open its local theatrical engagement two weeks from tonight on March 30. I want to thank the folks at Music Box Films for giving American audiences a chance to see this film on the big screen where it deserves to be seen. Also to Allied here in Boston for help making this evening possible, and especially to John Taylor for helping make the visit of Terence Davies possible. Immediately following the film will be a conversation about the film with its maker. Here to say a few words of introduction, please welcome Terence Davies.

[APPLAUSE]

Terence Davies 5:37

Thanks very much indeed. Still can't quite really believe I'm here. My first film at seven was Singing in the Rain, and for me, growing then, America was the land of magic and color, and music. I was lucky to be growing up when the great musicals were coming to their close. Nothing is like it from your country. You've given that to the world is one of the great cultural bequests you've given to the world, along with the Great American Songbook, which runs from Jerome Kern to the present genius of Stephen Sondheim. You've given that to the world. It changed lives, it changed mine. Little did I think when I was watching at seven Singing in the Rain, that I would ever, ever make films myself, much less come to America. And I cannot tell you the amount of gratitude I feel towards that and your country. You've always made me very, very welcome, indeed. And now my second appearance at Harvard. Even better. But it was made with the most modest of intentions and the most modest budgets. It was shot for 2.5 million pounds, and we shot it in twenty-five days in bitterly cold weather. Rachel really was a Trojan. But I am very proud of all of them. And I don't really see it as my film, because from the moment I wrote the script, to the moment we got the first show print was just slightly over a year. I mean, that's very quick, especially in England. And we thought, “Well, it might be shown in London for a while, a few arthouses, you know, around the country, and then it'll be quietly forgotten.” I didn't think an American distributor would pick it up. Music Box did. And this is the last part of a big tour. Miami, San Francisco, San Jose, Los Angeles, Chicago, New York. I'm now here. Thank you for coming. And remember, I am British, so please be gentle with me.

[LAUGHTER AND APPLAUSE]

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Terence Davies

–and I said. “I happen to have a point five Magnum, would you like to borrow it?”

[LAUGHTER]

David Pendleton 8:23

Maybe I'll start by asking you one or two questions, and then we'll open it up to questions from the audience. But speaking of the ending, I mean, it seems to me if we go back to– Well, this film begins where The House of Mirth ends in some ways, which is a woman committing suicide or trying to commit suicide, but at the very end of the film, she actually sort of recommits to living out her situation and going back to life. At least that's how I read the close of the film.

Terence Davies 8:50

Because what she's found, ironically, is true love. Originally, it was obviously sexual love. She finds sex at forty, which is why she's overwhelmed by it. But real love is when you can actually say to someone else, “If you're better off without me, I'll let you go.” And she holds him for just a short time in the last scene, when she wants to do his shoes and they don't need cleaning. It's just before she finally says “You can go.” But she reaches true love. But she reaches true love two scenes before. She doesn't know it. It's when Mrs. Elton says, “Lot of rubbish is talked about love. Real love is wiping someone's ass and keeping on going with your dignity. Suicide, no one's worth it.” And that's the point where—although she doesn't know it—that's what makes her go on. But the very fact that she can let him go, that's enough. And I think her future is bleak. She's not trained for anything, but she decides to live and go on and I think that single act is heroic.

David Pendleton 10:00

Can you talk a little bit about adapting the play for the screen? In part, I’m thinking of the ending because as I understand—I haven't read the play—but I understand there's a supporting character who’s sort of important for convincing her or a certain support for her for going on.

Terence Davies 10:15

The problem with the play is that the whole of the first actors' exposition, you know, Mrs. Elton tells you everything before the Colonel rose. And it was clear that Terence Rattigan didn't live in a bedsit in Ladbroke Grove in 1952. Clear because she's a joke, really. She's a caricature. She's everything except looks and mercy, you know, and I thought that's got to go. And as soon as I said, “Look, it has to be from Hester’s point of view,” then most of the exposition can be dropped. In fact, the whole of the first act is basically contracted to nine minutes. And so that any scenes in which she is not privy to or part of has to be dropped, because it’s her point of view. That made it much more interesting, because then it's still an impressionistic, linear narrative, but you can start with her drifting in and out of memory. Because what will she be thinking of if she's going to kill herself? How she got there. And it's such a simple cinematic device. It's really old: you show a woman, two men; there has to be a connection between them. And what is that connection? And the film tells you that. It's been used a thousand times, most notably at the beginning of Mildred Pierce when Zachary Scott gets shot, falls on the floor and says “Mildred, Mildred.” If it was Mildred who killed him, then there's no film. The exploration is who killed him. But it's such a simple device.

David Pendleton 11:38

To what extent were you aware of sort of returning to some territory that you'd worked earlier, because you're talking about turning the play into Hester’s memory and re-ordering it along the lines of her memory. And it seems like so much of your, your first features have that same kind of associative narrative where it’s not so much chronological but a working out of memory.

Terence Davies 12:01

But memory is fascinating. Because it's not in the past. The past is not a foreign country; it lives within us. In a second, you can be back forty years. Smell grass, I’m immediately back in my primary school. You hear a song, you're immediately back twenty-odd years ago. It's very, very potent. And one of the reasons I'm obsessed with the nature of time. Because the problem with cinema is awesome, it's always in the eternal present. When you cut, it's always assumed by the audience that this is the next thing that happened. And that can be very constricting.

When I was sixteen, we got our first television. And over four nights, Alec Guinness read from memory, all of the Four Quartets. I had no idea what they meant, but I went out and bought them. And I read them literally every month, because that is about the nature of time, memory, and actually the terror and the ecstasy of being alive. “Prufrock” is even better. And he wrote it at twenty-two! Talented swine! That's what I say. But I am obsessed by time. And when I was growing up, my father was very violent. He died when I was seven. But my sisters, and my brothers talked about what had happened to them. And they were all good storytellers. It was fantastic if they went to the pictures, and they told you what the story was, it also made it alive. And they just talked all the time about what had happened before I had been born. This became sort of part of my psyche. And so I've always been intrigued by the way in which you create time, whether it's emotional time, temporal time, or a mixture of both. And that seems to me to be so powerful. And this is really a little bit of flashback. But it's mostly impressionistic, linear time. But small things expanded like this, big things like that, contracted. That's what cinema does. It shows tiny detail which would be lost on stage. But when you see it in close-up, forty-feet high, it's really powerful. And it's a very simple thing. But when Freddie leaves, on the settee is the book of sonnets that William had given her. On top of that, Freddie’s gloves. She actually picks up the gloves. The reason that was there– Because in the play, she picks up a jacket. My mother died in 1997, and she was the love of my life. And I had to go and collect some of the posters that she’d kept, you know, of my work. And on the bed, were just here little red slippers, that's all. It was heartbreaking simply because the slippers were her. I've never forgotten that. And I thought, “I want that kind of power just to be in something simple.” Not a jacket. That's too clumsy. But something small. Driving gloves which you could buy anywhere. But there he is.

David Pendleton 15:16

It also seems like she smells them too, and the connection between smell and memory is so powerful. But in your film, it seems like sound is really important for evoking that. I mean, the film starts in complete blackness, but we hear the sound of rain falling, which immediately somehow evokes a sense of place, and I'm wondering if you have any thoughts about the relationship between sound and memory?

Terence Davies 15:40

Well, sound is really really important, but so is lack of it. What it's silent, it can be very, very powerful. One of the great scenes in the whole of American cinema is when Arbogast goes into the house and we follow him. On audio here are the strings played with their mutes on and they just shimmer. That's all you hear. Go into that room with Vera Miles, and it's sinister. What is he showing you? A large wardrobe, a dressing table, brass hands crossed on the dressing table, and you feel chilled.

When you take one close-up of one person, another closeup of another, you put them together, no sound. The first thing everybody thinks is: what is the relationship between these two people? Because there has to be one, because we love stories. And we're interested why we see these things. Put a ticking clock over it, what does it say? are they waiting for each other? Are they waiting for someone else? Put, say, a siren over it. Is the fire brigade coming to their flat or going somewhere else? It's very, very simple. But when it's powerful, when the images are allied to music and that is right, the audience know it.

The very first film I saw at seven was Singing in the Rain. The great big number in it, which is one of the GLORIOUS of cinema is from eight positions. That's all. Nine cuts, eight positions. That's all. And it is utterly seamless. And it feels as though it goes on forever. You can't forget that. Just even bad films like The Big Country: you hear that Jerome Moross score and it is thrilling beyond belief!

David Pendleton 17:48

By the way, just to do the prosaic thing, the film that he was talking about earlier with the private detective Arbogast and Vera Miles is Psycho, for those of you who didn't know.

Terence Davies

Arbogast, the Musical.

[LAUGHTER]

David Pendleton

I have to mention, there is an Anatole Litvak film version of The Deep Blue Sea—which I haven't seen—but with Vivian Lee as Hester Collyer. Is this something that you watched at all? Or did Rachel Weisz watch it?

Terence Davies 18:16

No, no, she didn't. And I think it was right that none of the cast watched it. I was taken to see it in 1956 when it came out. I was eleven. And I could only remember one shot, kind of coming down the stairs. But we saw ten minutes of it on YouTube. It's awful. They've just photographed the play. And you see this tiny little house, then you cut in and these huge staircases. It's like a mansion. This is no Ladbroke Grove, I'm sorry. And her performance is just awful. I mean, it's unwatchable. And Kenneth More, unfortunately, is about as sexy as a coffee table. [LAUGHTER] Although he did give one great performance in Sink the Bismarck. It’s wonderfully understated, but most of the time, most British actors of the period were oak from the knees up. I mean, really painful. And in the 50s they all spoke [CHANGES HIS ACCENT] like that all the time. You know, you hear an American accent in the same period and the American accent is sexy! It's really sexy! And we tried to sort of get around it: the Rank Charm School training young actors and actresses, and they tried to make them hip, and it was painful. They'd say things like, [IN A STUFFY BRITISH ACCENT]: “That's when I heard him. Ted Heath’s new trombonist. Boy, oh, boy, has he got rhythm.”

[LAUGHTER]

David Pendleton 19:46

Could you talk a little bit about the origins? How did you come to choose this as a project? Because it seems like a really natural fit for you. Is it a play that had always meant something to you?

Terence Davies 19:59

No, the Rattigan trust approached me. They said, “It’s his centenary 2011. Will you do a film version of one of the plays?” I said, “Well, I've never seen any of the plays staged.” But I did see on television, the 1952 version of The Browning Version. It’s a wonderful performance by Michael Redgrave. So I couldn't do that. In 1959, Burt Lancaster did a version of Separate Tables, and it's really good. And I said, “I can't do that.” I said, “So I'll read the rest of the canon and see if I can do something.” And so I read all of the plays. And I said, “I think I can do something with The Deep Blue Sea.” That's how it happened. And at first, I was a bit disappointed because the story is really rather unremarkable. But it was only when I knew what the subtextual meaning was that it came alive—of the nature of love. It's a ménage à trois, and it's about love unreciprocated, and they all want a different kind of love from each other. And that's truly tragic. It's also truly human. Because love is peculiar to us as a species. We’ll l lay our lives down for someone we love. We will also destroy them if we're betrayed by them. It's extraordinary that we are the only species that feel it. Eliot put it perfectly. What he said: “Love is most nearly itself, when here and now cease to matter.” That's a wonderful definition of love.

David Pendleton 21:36

Are there questions in the audience? Or else I will go ahead and ask more questions. Okay. There's a woman here in the center. Kevin, can you come down? We'll pass you a mic so we can all hear your question, okay?

Audience 1 21:55

Okay, I'm afraid this question may make you realize that you're at Harvard. But do you think that Rattigan, the way he wrote that, that Hester was intended to be a metaphor for England—going through the war and coming through it? I was thinking particularly about her upbringing, kind of uptight and then all of a sudden, everything's blown away.

Terence Davis 22:21

No. The other myth that’s grown up is that it's a coded homosexual play, but it's not. A, you couldn't have got it on in England, because it was against the law until 1967, to be gay. And Frith Banbury who directed it in 1952 said this– You know, “Is it coded?” He said, “No, his lover had killed himself by gassing himself, and he'd use that incident.” But if you're not British, you don't share this thing. The war was the last great moment for Britain. I mean, we came together as a nation as we've never never been since. For nearly two years, we fought Nazism alone,. Had Hitler gone and invaded in 1941, we would have been occupied. We couldn't have resisted. So even now, it has enormous emotional impact for Britain. It was the last time we were actually important. But we did stand alone, and we did come together, and we decided to fight. Since then, the country's, you know, gradually imploding more and more, and what's been revealed over these last two years is how corrupt it is. Really, really corrupt, which is really shocking. But then it wasn't. It was a question of absolute survival. You either fight or you give in. And we decided to fight. And what's really shocking about the period during the war anyway, the queen mother wanted Halifax to be prime minister, not Churchill, and Halifax wanted to have a peace with Hitler. That's so scandalous, but then the royal family are just such parasites anyway. [SCATTERED APPLAUSE] But, it has left a deep scar on England because, you know, we were within a hair's breadth of being occupied. And at the end of our street was a little shop. And it was bought in 1952 by a German lady called Lotte Starke. And for some reason, she took a shine to me. And I said to her, “Well, what was it like during the war?” and she said, “Well, we were terrorized. You had to have a copy of Mein Kampf or the Gestapo would come around. And if you didn't have a copy of Mein Kampf, you were sent to either a labor camp, or”–. Her mother didn't have one, and she was sent to the Russian front, as a typist. I mean, we can't in England know what that’s like, because we've never been occupied. And it's so deep on the British psyche of the war. And you must remember, after the war, we were flat broke; the country was bankrupt. And when Tony Blair became Prime Minister, we just paid off our debt to the United States. It took that long to pay off. But what was extraordinary after the war was we had this Labor government of 1947, which was the most radical we've ever had in our history. How wonderful they were! It's a wonderful government. I’m still Labor by conviction, but what lingered on was the attitude towards where you behaved, that lingered on from the war, before the war. You had to behave in an honorable way and socially responsible, as well, to other people, I mean, people literally did say, “If you watch Brief Encounter, it's accurate.” They said, “Good morning,” they said “Good day,” they said, “Good evening,” they were polite. But that was already beginning to implode. And now we're seeing the results of that. And now, this unimportant little island off the coast of Europe, still thinking that we're important. That's really pathetic.

David Pendleton 26:21

It seems like that's related, actually, to Freddie's character in this movie, right, in that he was involved in the war and something important to now he feels that the best part of his life is behind him already.

Terence Davies 26:31

But you must remember those lads were between eighteen and twenty-two when they were fighting in the Battle of Britain, and sometimes fighting six or eight sorties a day. And when you saw a Luftwaffe aircraft, the response time was eight seconds. If you didn't respond in eight seconds, you were dead. So he saw a lot of his friends killed as lots of people did. So when he survives, one of the reasons he’s angry is because he feels that she's prepared to kill herself for something he thinks is trivial. What he doesn't understand, when you're in the thrall of sexual love, everything is important. They come home late, you're filled with dread. They don't remember your birthday, you're deeply hurt. And he doesn't understand that.

David Pendleton 27:19

There's a question here, and then we'll get back there, and over to you.

Audience 2

I was curious, it's such an exquisite film, and some of the juxtaposition of the images, I'm just wondering how you adapted the play to that. I'm thinking in particular of they’re in the museum, and his reaction in the museum, and then you cut to the bar, and her reaction to the singing, or the husband's incredible glance in his car, then you go to the landlord. And even when she looks out the window at the end, she's got a little smile on her face. And then you move the camera to the rubble which will be rebuilt. So I'm wondering at what point you come up with these images and how you adapt them from the play.

Terence Davies 28:00

Well, it's something that is instinctive, like the use of the Barber, which is one of the great violin concertos of the 20th century, and along with Knoxville, his two greatest works, and you should go and buy them tomorrow. But if I see it and hear it, I know what to do. And the point of being in the pub, and the point of going to the gallery, is that she makes an effort for him. When he goes to the gallery, he’s bored, he makes a silly joke. He doesn't understand that you have to make an effort. When he finally gets in, she's listening to the Barber on the radio. He switches it off. “Let's have some music with a bit of life in it.” He wants to listen to the live program, which is basically comedy and dance music. You know, it was to point up the cultural differences. Whereas with William, he was cultured. He probably took her to the opera, to the ballet. And she probably thought like a lot of people did those days that, you know, he may have had a small libido, but men and women were much more naive about sex. It wasn't as ubiquitous as it is now. And she probably thought, “Well, that's what marriage is,” and then she falls in love, sexual love, which completely turns her world upside down. But it was important to show just a little bit of where their differences lie, and then those scenes are not in the play. Like the scenes with Mother are not in the play. And I was pressed to drop the scenes with Mother and I said, “No, I'm not. They tell you a lot about William.” But I don't know where it comes from. I mean, I just know when it's right, I feel it. And I knew it needed to be opened out a little.

But also it's partially autobiographical. On a Sunday on the live program on BBC, it was something called Two-Way Family Favourites, and it was for all the British forces, which were dotted around the world, Akrotiri and Berlin and all that. They would send requests in, and the families at home would send requests in, and they played records. That's what it was. And one lovely Sunday morning—it was really, really lovely and warm—my mother switched the live program on and they were playing Joe Stafford, “You Belong to Me.” And I walked out into the street, and all the doors and windows were open. And everyone was listening to Joe Stafford. I mean, you can't forget that. I mean, you just can't. I thought, “I've got to have it in,” because it's such a wonderfully romantic song. But it has a double meaning. It's about possession as well, not just love. And when we did that scene—and it's one of my favorite bits in it—because we did it, I think, ten times, and every single time, Rachel looked as if she didn’t know the words. It's just a wonderful piece of acting. Wonderful.

David Pendleton 31:01

Well, can I ask you a little bit about music, then? Because it seems like in your films, music is such a communal experience in a way that I don't think it is today. I mean, the idea of like the entire pub singing along, for instance...

Terence Davies 31:12

But that was common. And it was absolutely common. What happened, people went to the pub at about half-past-seven. By about nine o'clock, they were feeling a bit merry. So that sort of thing. Everyone knew what the communal songs were, everyone knew whose personal songs and one Christmas I remember going up the main road, and there was a pub on every corner. And every pub was singing. It was just wonderful. People sang things that they liked, but what of course they were doing, they were singing their feelings. And most of them are from the Great American Songbook, another great cultural legacy that you've left to the world. Because the great songs are actually as good as anything by Schubert and I don't say that lightly. Because they give expression to ordinary people who can't have that expression, as well as being very, very romantic. And some of them, very, very witty. The wittiest of all, of course, is Cole Porter, whom I absolutely adore. That wonderful song from Kiss Me Kate, “Brush up Your Shakespeare”—“If she thinks your behavior is heinous, kick her right in the Coriolanus,”—which I think is a wonderful line! But it was popular song and most of it was American. Occasionally British songs were good, but mostly American. And they were, as I say, poetry for the ordinary person.

David Pendleton 32:42

There was a– Yes, that gentleman back there and then you.

Audience 3 32:48

My question is another where-did-it-come-from question. For me, part of the evocative richness of watching the film were visual echoes from other movies about similar relationships. Maureen O'Hara looking through the window of the upstairs room in How Green Was my Valley. One of the images reminded me of Brief Encounter. Later in the movie, I got echoes of Neil Jordan's version of Graham Greene’s The End of the Affair. I wondered how much of that was instinctive, or accidental and how much of it was deliberate and conscious.

Terence Davies 33:24

I mean, I stole from a lot of it. But I stole subconsciously, so we call that an homage. But there are two things which are taken directly from Brief Encounter: when she goes to the tube, and you see that the tube train go by—that's directly from Brief Encounter. When they're sitting in the library and they're listening to the Barber that's taken from Brief Encounter as well. There were influences which were subconscious. When I was growing up my sisters took me to see things like All That Heaven Allows, Magnificent Obsession, Love is a Many Splendored Thing. And then I discovered on television, in a series on BBC One on Sunday afternoon called Love Story. And they showed on Love Story, Letter From an Unknown Woman, The Heiress and Night of the Hunter. So you can't not see these films and be hugely influenced by them. Hopefully, that influence comes out refracted. But of course it's there. But I have to say the opening and closing shots, the inspiration was from the opening and closing shots of Young at Heart. That's the first time I saw Doris Day and fell absolutely in love with her. And when I grow up, I want to be Doris Day.

[LAUGHTER]

Audience 4 34:53

There was that scene when she's about do it again in front of the train, and then she thinks back on the time in the tunnel during the war. And she doesn't end up throwing herself in front of the train. Your discussion earlier about the power of memory and time. And I'm just wondering, I mean, from my vantage point here, it seemed that the moment when she starts to think about that just distracts her from throwing herself in front of the train, and she doesn't manage to, she sort of misses the chance. But then she doesn't wait for the next train. And so I wanted to hear something about that.

Terence Davies 35:43

Well, I'm a great believer in the fact that a lot of life is arbitrary. It's simply arbitrary. And that's what in a way is terrifying about it. Because once you lose your faith– I was a very devout Catholic, and now I'm an atheist and that's comfortless. But small things have always, always moved me. During the war, London was bombed seventy-two nights in a row. So was Liverpool, because it was a dark area. My family were in—this was before I was born—in a shelter adjacent to another one. The other shelter got an indirect hit. It burst all the hot water pipes and all those people were scalded to death. People went down into the tube against the law. Initially, the government didn't want them to do that. But because the London Underground is so deep, you know, they were safe, but of course, I had no idea what was going to happen when they went up after the air raid. But they sang, some of them danced, they played cards, just to keep terror at bay. And when you keep terror at bay communally, it is more comforting, I think.

But the reason she doesn't throw herself in front of the train or indeed wait for the next one are two reasons. One, having thought about this little incident during the war, she can’t go ahead with it. Also, it's the Northern line, and the trains don't run that frequently.

[LAUGHTER]

David Pendleton 37:20

Are there other questions? Yes. There's a couple down here. We’ll start with you, and then you, Sir. If you look to your left...

Audience 5 37:27

Yes, I wanted to ask a question about Freddie. I mean, so much of the film's focus is really on her. But it's clear pretty early on that she's suffocating him and he has to get away. He wants to get away, and his cruel and callow act of throwing the shilling at her and saying, “Put it in the gas meter.” Okay. But then we come to the end and the last scene, and he's still leaving, and he wants to leave, and he's leaving. But we see him much more sympathetically in the last scene. And I'm having a little trouble getting from the crueler, more callow, shallow aspect of him to the last scene.

Terence Davies 38:26

Yeah, so that's fair enough. But the point I was trying to make was that none of them are villains. You know, I mean, after that scene where he’s shouting at her and Collyer in the street, you would expect that row to continue, and it doesn't. And that's what does happen in real life. And he says to her, “I'm not a sadist. I don't want to hurt you.” But he doesn't really want to leave either. He's making a big effort himself. It's about unrequited love. That's what it's about. And when people are in that thrall—and it is a thrall—they may behave not honorably, but they don't behave cruelly. That's the difference. And he's damaged, you know, what's he going to do as a future? He's going to go out to South America, possibly crash when he’s testing planes, or he’ll live to be fifty or sixty. He'll prop up a bar, being a drunken bore telling the people that he actually survived the Battle of Britain. It's not a pleasant future. It's not a pleasant future for any of them. But I don't think it's anomalous that his moods swing. You must remember he's only twenty-five, twenty-six or twenty-seven. He's certainly not even thirty. And I think it's convincing, but you know, I made it, so of course, I would say that. [LAUGHTER] But you have to respond viscerally, and if you feel that way, that's absolutely valid. But I'll introduce you to my therapist. [LAUGHTER] He's a really great therapist. Even he hates my father now. [LAUGHTER]

David Pendleton 40:16

There was a question…. Oh, yes, here, the gentleman in the blue sweater.

Audience 6 40:21

Terence, it's really great to see you making movies. I met you actually in ‘85 in Dublin, and you brought over your trilogy, and that was such an amazing experience. And just to see you making movies, continuing to do that, it's just really, a wonderful thing. Three things pop up. One is the use of music in all your movies, I love—especially in the Liverpool movie, but in everything. And the other that really, really strikes me is you are, at the end, an optimist, something always that's profound about that. So there are two things, I can't remember the third. But anyway, really just wonderful, wonderful to see you here.

Terence Davies 41:00

I don't feel an optimist though. I do see the glass as half empty. And I think it was because something died in me a long time ago.

Being gay, which I hate, and being from a large working class family where it was not talked about. And in England, it was a criminal offence until 1967 in the Wolfenden report. And when I got down to London, and I went just to two clubs, it was so chilling. You know, the worst was actually coming to Castro in San Francisco. And I came at a time when it was glad to be gay. This was just prior to AIDS, and where the Trilogy was concerned, which is actually about my despair about partially being gay. It was met with great hostility. Great hostility, indeed. And one journalist said “These films make Ingmar Bergman look like Jerry Lewis,” which is almost memorable. [LAUGHS] But it's hard. You know, I'm not getting any younger. I'm sixty-six. You know, I go home and my furniture is younger than I am. [LAUGHTER] And I really resent that. But I don't think I am an optimist. Really, I hope I'm like my mother, who was still a stoic, not in the Greek sense, but in the sense of, “Well, these are the cards you were dealt, you've got to get on with it.” But there are times when, yes, of course, I despair. When I can't get things off the ground. I didn't work for eight years. No one would give me anything. That erodes your soul because it really, really erodes your confidence. And you think, “Well, perhaps no one wants to see what I've got to say anyway.” Because I don't do a lot of quick cutting. I don't have actors running around shooting one another, and explosions. You know, because certainly one thing worse than an actor with a gun that's a British actor with a gun. [LAUGHTER] Really bad, really bad. And I was once sent a gangster script, and I said, “Look, what do I know about the gangster world?” Nothing. Someone said to me when I made my first feature, which was reasonably a success, “You've got to go into sex, drugs and rock and roll.” And I said, “Well, I'm celibate. I don't like rock and roll. And I won't take drugs. What's left? Soft furnishings. Not exciting!” I said, “If I did a car chase, it would be two cars going slowly.” [LAUGHTER] Not foot-tapping. Not funky.

David Pendleton 43:35

With “Que Sera Sera” or something in the background.

Terence Davies

[LAUGHING] Yes. Her too! Thank you!

David Pendleton

Actually, one thing that I was curious about—because there are certain filmmakers who work really quickly and some who work really slowly—and I'm wondering to what extent your rhythm– I guess some of it’s been dictated by waiting for financing to come through, but I mean, you said you shot this quickly. Are you somebody who you think would work more quickly if it weren't a matter of raising money every time or...?

Terence Davies 44:08

Well, I've always worked with the money that I could raise. This cost 2.5 million pounds, and we shot it in twenty-five days. You know, I come in on time and under budget, I always do, because there's still that residue of Catholicism. And I think, you know, this is other people's money. I can't waste it. I get really frightened. Really I do, honestly. But I don't know. The problem with making films in Britain is we don't have a proper film industry anymore. It's a cottage industry, and it's at the mercy of every new orthodoxy. When I first started in the 80s, it was semiology. God that was exciting. [LAUGHTER] Then it was the Robert McKee stuff, which is utter nonsense. And then it's something else now. Everything's got to be genre. And if you say, “Look, it's not a genre; it's a story,” and it all goes quiet in that very, very British way as though you've just peed on the french fries. [LAUGHTER] But in England, there's something about the English society, I think that it's easier to say “no” than say “yes.” And you go to these grisly meetings, where you just know that they don't want to do it. And you say, “Look, if you don't want to do it, why don't you just tell me? Let's get the agony over with.” It's different in the United States. You know, the money's there, but then you still have grisly meetings. When I was making House of Mirth, every single meeting, I had, lunch or dinner, it was “Why does she have to die?” And I'd say, “Well, have you read the book?” [LAUGHTER] “No.” “Well, if you read it, it might give you a clue.” [LAUGHTER]

Anyway, I got fed up with this after a while, and I thought, “I'll try a new tack.” And we went to this grisly lunch, where someone leaned across the table and says, “Why does she have to die?” I said, “Well, the natural tragedy is that the beginning prefigures the end, and supposing Lear had not split his kingdom into three, then there'd be no tragedy.” And he said, “Who's Lear?’ [LAUGHTER] I said, “He's just got a new album out.” [LAUGHTER] So it's always a problem.

David Pendleton 46:28

There's a question in the back, and then a question here in the middle. If one of you can go to the back, and one of you to the middle. Hang on, there's a mic coming. Let's do the back first.

Audience 7 46:40

Hi Terence. I just wanted to say I just saw Distant Voices, Still Lives, and it made a huge impact on me. And kind of going off of that, thinking of a legacy of films that intertwine violence in the working class experience, I was wondering if you could just comment on that. And if you feel like that's something that you're going to address again, at some time in your career.

David Pendleton 47:06

Do you mean like domestic violence? Is that sort of what you're thinking of, or violence in general?

Audience 7 47:10

Well, definitely, in Distant Voices, Still Lives, we're talking domestic violence, but just in a broader sense, it seems like there's a constant intertwining of the working class experience and violence in England.

Terence Davies 47:26

Well, I don't know about other people, but my father was psychotic. And had I put everything in that he’d done, nobody would have believed it. I had to keep it down to the bare minimum. I'll give you an example. I was five, I think. On one night, my mother and I slept on the sofa in the parlor. We didn't sleep in a bed at all until after he died. And he just jumped up from nowhere, threw her on the floor and picked up an axe. He was gonna chop her head off. Well, you know, when you're five, you don't understand that. You're just terrified of it. And it usually was preceded by these dreadful silences. And so much so that if there's violence in any film, I can't watch it. I just can't. It’s too painful, because of it being arbitrary. And my mother told me a heartbreaking story. My eldest sister had a lovely friend called Mickey Kelly. She's in Distant Voices, Still Lives: Monica. And my mother opened the door. She was never allowed to go out. And Mickey said, “Are you alright, Mrs. Davis?” She said, “Can you comb my hair, Mickey? He won’t let me comb my hair.” It was awful. It really pierced my heart that anybody who was so full of love as my mother was, this bastard could be so vile, not only to her, but to his children as well. And it leaves a scar on you. It really does. I don't know how you get through that. I've tried therapy. It's helped but it doesn't get through to the nature of how arbitrary that was. And then when he died, I had my little four years of paradise. And then I went up to secondary school, where I was beaten up every day for four years. It's left a deep scar on me and it's left deep scars on my family, I can tell you, because the worst thing about it is that it's arbitrary. And when I see films where they just use violence for the sake of, I think I want them to be in a room with a psychotic just for a day. See what fun it is. See how entertaining it is. Not fun at all, believe me. I hate it with my entire being. And if I see it, I've got to say something. I've just got to. If I see it, I stop it. I'll interfere. I don't care whether, you know, I get stabbed or shot. I just won't put up with it, because I think it's wrong. But it's left a dreadful, dreadful legacy to me and my family. How people can behave like that is utterly beyond me. Utterly beyond me.

David Pendleton 50:17

There was a question in the middle.

Audience 8 50:19

Hi, I wanted to ask you about your work with Rachel Weisz and how that performance was developed by the two of you, I'm assuming. I felt like she raised to a different level as an actress in this movie. I've seen her in a few other movies. But I thought it was a very hard character to sustain in many ways, because even though the higher goal is true love, she's very much defined by this man, which in this day and age is not necessarily something that an actress would be wanting to portray. So I'm interested in how you worked with her and what she brought to it. And what other actresses from the past or from today were inspirations to both of you?

Terence Davies 51:09

Well, one of the inspirations was, funnily, violence. I said, “When they row, it's got to be ferocious, it's really got to be ferocious,” because they're both fighting, in a way, for their emotional lives. So much so that in one or two of the takes, Tom is losing his voice. Already, it's sorted to rasp, but it gives it an extra something. But you bring things to it that are subconscious. I stood outside pubs as a kid, like every other child on my street. So the way in which it's framed is because of that. And the way in which they sing is because I listened outside, and when I was old enough to go to a pub, when I was eighteen, I was there with my family, and they did just that. But all sorts of things influenced you. All the films I've ever seen have influenced me, particularly English comedies of the 50s, which were just incomparable, and the late 40s. And the American musical, and indeed some Westerns. I mean, Rio Bravo, and particularly The Searchers. The Searchers is a wonderful film. And you can't forget that. That wonderful rich color and wonderful shots at the end when the door closes, and it's an echo of the opening shot and they walk into the dark, and he goes out into the sun. I mean, just breathtaking. Breathtakingly beautiful. So I'm influenced by all those things as well. And half the time you don't know what those influences are. You just do it.

David Pendleton 52:49

When you worked with Rachel Weisz, did you guys talk about performances from the past, for instance?

Terence Davies 52:55

No, no, not at all. She said herself we didn't have time on twenty-five days for any navel gazing. There just wasn't time. Sometimes she'd come in and say, “Can we go straight away?” And I'd say, “Fine. Let's go straight away.” Other times, I'd say, “Well, by the fourth or fifth take, we've sort of got it.” And she said, “Can I do one for Jesus?” And I'd say, “Yes, let's do one for Jesus.” But you have to feel that on a shot-by-shot basis. Some days they come on and you know they're just on form. I mean, you don't have to do anything. Other days, they come in and they're not on form. Today, they may have got out of the wrong side of the bed, they're tired… The days are long, and they were very cold. So you have to guide them through the takes. But it's six of one and a half a dozen of the other. And you can't ever guarantee that it's going to be smooth. Because we're all human beings. There are days when, you know, I didn't feel like going into work. Driving out to Bow, which is in the East End, is pretty depressing because it's so ugly. It's one of the ugliest parts of London, and you drive through Streatham, and then into the East End, and you just think “God Almighty, kill me now,” but you can't let anyone know that—just as I was restricted the amount of stock I could use. I had agreed that I would use only 150,000 feet of footage, but you have to let the actors think that they can do it forever. Even though you're thinking, “Oh, god, please let us get it now,” because the opening and closing shots literally took all day and all night. And that uses a lot of footage because it's a very long shot. And so is the bit in the tube and it eats up the footage. Luckily my ratio is usually about fifteen-to-one so I knew I wouldn't go over and they were lovely. They said, “If you go over, of course we're not going to not buy stock.” I said, “But, no–” Because being an ex-Catholic, you see, I said, “No, that's what I've agreed to.” [LAUGHTER] Dim!

David Pendleton 54:59

There's a question back there. Dan, can you pass the mic? If you look to your left, sir?

Audience 9 55:09

Thank you. Speaking of films, I'm just curious why you shot film instead of digital, and I was just curious about that.

David Pendleton 55:15

Can you talk a little bit about the choice to shoot on film as opposed to shooting digitally?

Terence Davies 55:20

Well, I always do the same thing. I do tests to find out the look, because every film has got to have a look. And then all the tests on various forms of stock or whatever, we just run them. And so, “That's the one.” It's always film. Because film’s got just more subtley than digital, but digital will take over. It's as important as the coming of sound. It just will, and what they can do digitally if there’s a shot that's unsteady. I mean, the best shot that we got in the tube station was still unsteady, because we were on the actual rails, and they took out every bump. I mean, that's astonishing. That's astonishing.

The problem with digital is that you've got to have time to think. There are times when you’ve got to say, “No, I need two days to think. I'm not making my decision now.” Because you can do a cut, you know, in an hour, even for the longest film. In the old days, if you wanted a series of dissolves, it took most of the morning to mark them up on chinagraph, because you physically had to do it. But you've got to fight for thinking time. And the quicker it gets, the shorter will be the best production period. And that that is a worry. That really is a worry, because you've got to fight for that. You really, really have.

David Pendleton 56:42

You're talking about time to think in the post-production.

Terence Davies

Yes.

David Pendleton

In the post-production process and the editing process, right. Can you say a little bit about developing the look of the film and your work with the cinematographer, because it's so extraordinarily dark with these very rich colors. Darker than than your other films, it seems to me.

Terence Davies 57:01

I when I was growing up, I mean, I grew up in the 50s, and I know what it looked like. But more importantly, I know what it felt like, and that's different. The color range was very narrow. You saw very little primary color, very little. But that isn’t to say that it was drab or dismal. And in September, when I used to come home from school, at four o'clock, it was always dark. And everyone had a parlor, which they kept absolutely pristine. And it was very old furniture, but polished to within an inch of its life. And I'd come in, the fire would be lit, there would be toasted potato cakes on the hearth and a pot of tea. And the fire was reflected in all the furniture. And it seemed sumptuous. It seemed so rich. And to a child's eye, it is. It was. So it's knowing that restricted palette, but how rich that restricted palette was. And that's what I remember. And pools of light, because most people only had electricity in the parlor. In the hall, if you were lucky. A lot of people just had gas, which gave it this curious green quality to the light. And if you see pools of light and darkness, but in the darkness, there's texture, it's extraordinarily beautiful. And it's dead simple. You know, it's just placing lights where you want them. I mean, Florian is a young man of genius, I think. You know, James Merifield, who designed it for me, Ruth Myers who did all the costumes. To get that claret coat, which looks sumptuous and sexy against a relatively drab background. It's just so fabulous. But you can only know its voluptuousness because the the color range is narrow. But that's the magic of watching a film and it has to be magic. If you don't get the first two minutes, go home. No point in staying. There's no point in staying because you’ll completely misinterpret it throughout the entire film. But when you love something, and you really believe it, like Letter from an Unknown Woman, which is in the most ravishing black and white. I mean, it is ravishing! You believe it as soon as you see it, and and in terms of color, of course it's much narrower, but it's all about gradations of white, to gray, to black. So there's a wonderful scene where she puts her child to bed and turns towards the window. She's wearing a white opera dress, but the whole of her back is bare and it's so sensual without being unseemly, if you see what I mean. And the two scenes that we did in the bed, I said in the script, “These are not to be explicit. If you do not want to take your clothes off, don't take them off.” Because I wouldn't do it, and I think it's a lot to ask of actors. And they were real Trojans about it. They said, “No, we've got to do it,” because then it becomes about flesh and flesh and cloth, and just the red varnish of her nails. And that’s sensual without being erotic. It's very, very sensual. Because my sisters all wore majestic red nail varnish, majestic red lipstick, and I used to go and buy their nylons and Evening in Paris perfume, which I'm sure smelled like some kind of disinfectant, but we thought it was so sophisticated.

David Pendleton 1:00:50

Are there other questions? Oh, yes. There's a question up here. Hang on. There's a mic on its way. Yeah, you, sir. Hang on, but reach behind you and grab the mic...

Audience 10 1:01:03

A very prosaic question, but particularly in the United States—I assume in Great Britain also—public health figures are very adamant that directors remove smoking scenes from movies, particularly for movies for kids under thirteen. What I'm curious about is when you're depicting the 50s—when, I think, about eighty percent of male Britons smoked—did this cause any kind of awkwardness or self consciousness? Any comments you might have on this?

Terence Davies 1:01:38

No, we didn't. Everyone smoked. Most of my family smoked, and I thought it was incredibly sophisticated. I never did. I just didn't do it. But I loved watching my sisters and their girlfriends smoke. And those days, the cigarettes were untipped, so they always took a little bit of tobacco at the end of their tongue. So sophisticated! [LAUGHTER]

Audience 10 1:02:03

But then when you put it in a movie, present day, how does that interface with public health authorities here and there?

Terence Davies 1:02:11

We had no problem with it. What we had a problem with was when he says in the gallery, “FUBAR acronym: Fucked Up Beyond All Recognition,” we had to change that to “fouled up” because you can't swear on an aeroplane. You can show horrible violence, but you’re not allowed to swear on the airline version of the film. Ridiculous. But we had no problems with that. Because that's accurate. You can say, “That's what they did in the 50s.” I know, because I grew up. As far as I know. I didn't hear that there were any problems at all, just about swearing. Amazing.

David Pendleton 1:02:55

Are there other questions? Maybe I'll ask you one last question. Because we talked a lot about postwar cinema. I'm wondering about silent cinema. Because you're such a master of visual storytelling, I'm wondering if you're a fan of of silent cinema at all, if that's something that speaks to you in the way that some of the cinema that you grew up with, and also in terms of you know, the importance of acting and performance and camera movement, etc.

Terence Davies 1:03:22

Well, the silent cinema discovered film language. The first crane-up was in Intolerance in 1916. And they built a wooden tower, and they pulled it up by a rope. And that's the scene in Babylon, where you see all the extras go up and the huge elephants. Greed is one of the greatest films ever made, originally nine-and-a-half hours long, cut down to two-and-a-half. There are extraordinary images and extraordinary juxtapositions of images. The Wind is another. Lillian Gish arriving in the middle of the prairie, and this white horse rears up out of the dark. I mean, it's just extraordinary! And it really in a way, Night of the Hunter, which is not a silent film, but it's really influenced by silent movies and German Expressionism. The sequence on the river is one of the great, great sequences. Wonderful and a wonderful score by William Schumann. But all those things, they were discovering cinema language. Can you imagine? There's a story about D.W. Griffith doing his first close-up, the first close-up in the history of cinema. And the front office said, “Mr. Griffith, our patrons pay to see all of the actress, not bits of her.” And he changed the nature of screen grammar. I mean, that's what's so breathtaking. Yes, I do love silent cinema, but my heart is reserved for the American musical.

David Pendleton 1:04:53

Good for you. Well, thank you so much for coming. We hope you'll come back with your next film!

Terence Davies

Thank you.

[APPLAUSE]

©Harvard Film Archive

Related film series

Explore more conversations

Lee Jang-ho

Christian Petzold

Sky Hopinka

Jay Sakomoto