Films by Laura Huertas Millán introduction and post-screening discussion with Haden Guest, Laura Huertas Millan and Cecilia Barrionuevo.

Transcript

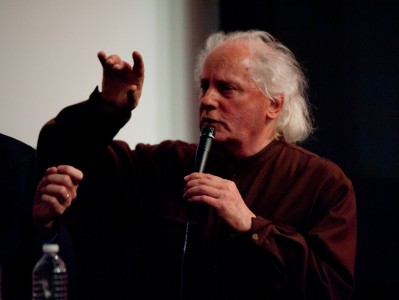

Haden Guest 0:00

Good evening, ladies and gentlemen. My name is Haden Guest. I'm Director of the Harvard Film Archive. I'm really pleased to be here tonight, to welcome back Laura Huertas Millán, who is a filmmaker and artist whose work has steadily and skillfully challenged the possibilities and limits of documentary as a mode of inquiry and as an art form. Her work is, I think, most deeply rooted in traditions of ethnographic and anthropological cinema, that she pointedly, yet also subtly, questions, and expands, by searching for ways to render vivid, experimental, experiential, emotive, and political dimensions of the subjects that she explores. All the while making subtly clear her own place and identity as creator and representer. The films we're going to see tonight are also shaped, in part, by Miss Millán's time spent here at Harvard, as a member of the community of artists, thinkers and scholars working in the Sensory Ethnography Lab. Following the bold charge provocatively, profoundly defined by SEL, Millán's films embrace and explore the fullest range of the sensorium, not just vision, but hearing, touch, and even emotion itself, as a kind of language without words, that speaks revelatory truths about human and non-human experience and memory, as they commingle to define a place, a time, an experience. Last night, we watched a thought-provoking and wonderfully intense program of films selected by Miss Millán, gathered under the rubric of “ethnofiction,” a term she has embraced as one way to loosely name the interstitial and richly ambiguous place between fiction and nonfiction that she's continued to mine. I was especially struck by the way a number of the films, which included, among others, works by Chick Strand, Malena Slzam, Lina Rodriguez and Millán herself, the way that these films explored landscape as a kind of witness, a primal force that clearly reveals the unique histories that have shaped it. But a revelation offered not through words, but through a kind of lyrical typography, kind of emotive archaeology. I was struck as well by the lyricism through which many of the artists weaved together intimate and the seemingly, intimate stories and the seemingly objective fact, subtly sharing hauntingly private stories upon the public space of the screen, while also reminding us, the viewer, of our place as outsiders, denying us any explanatory perspective. Laura Huertas Millán is a gifted writer and thinker about cinema, as I think her program last night, curated program last night, made clear. And yet, she's also found a way to avoid that most fatal of traps that plagues many filmmakers working within or around the university: the academic film. Quite the contrary, as is attested by tonight's program, which gathers three recent works, La Libertad, Jeny303, and Sol Negro, that each explore different and innovative modes of portraiture: communal, intimate, familial. We'll learn more about these films and about Laura Huertas Millán’s practice in the conversation that follows the screening, conversation in which Laura Huertas Millán and myself will be joined by Cecilia Barrionuevo, who is the Director of the Mar del Plata Film Festival. And she's also curator of a wonderful annual program, Neighboring Scenes, which is a showcase of Latin American cinema that takes place at Lincoln Center, just, the newest edition just closed, very recently, and it was, I was lucky enough to attend the opening, it was really quite wonderful. Miss Barrionuevo is also an editor of an important magazine dedicated to cinema, a journal called Las Naves, and so I'm really excited that she can be here, as well, for a conversation afterwards, a conversation in which you will also be invited to participate. I’d like to ask everybody to please turn off any cell phones, electronic devices you have, please refrain from using them. The films will play, one after another, with just the slightest pause in between. And now, with no further ado, please join me in welcoming Laura Huertas Millán.

[APPLAUSE]

Laura Huertas Millán 4:18

Hello. Thank you for being here tonight. Thank you, Haden, for this beautiful invitation. I'm really honored to be able to show my works here. The HFA was so important for me in my construction as a filmmaker and artist. I had the chance to be a student here for a year and, one year, one year and, this was my second home, I would say, so I'm tremendously happy to be able to screen my films here. And I'm really looking forward to our discussion with Cecilia and I hope that you will enjoy the films. Thank you.

[APPLAUSE]

Haden Guest 5:07

Thank you so much for this really wonderful program, for these three films. And we will begin with some conversation here, before taking questions from the audience. And there's a lot we can talk about, but I was wondering, maybe, to start from a more general... I'm seeing certain, oh, let's say, common orientations and strategies in the films and I love the way we began with La Libertad, which, with this evocation of weaving. And it seems to me that your films evoke a kind of, and use a kind of, weaving, of bringing together, at times, of seemingly disparate elements, that then the meaning slowly emerges, or perhaps, it's more of a feeling. And one of them is, I’m thinking about Jeny303, and this abandoned building, and then the figure of Jeny himself, theirself, as one of these examples of interweaving. And I was wondering, maybe, if we could begin with this, this pairing of this building. And then, and this, this story, this portrait that we have. I'm struck by so much, you know, his, or their voice, and then the sound of the silence and the void in this space. So I was wondering if we could talk about the pairing of this building and this figure and then there's also this idea, perhaps, of interweaving as a larger concept, if you will.

Laura Huertas Millán 6:41

Yes, so…

Haden Guest 6:43

It’s on.

Laura Huertas Millán 6:44

It’s working?

Haden Guest 6:45

Yes.

Laura Huertas Millán 6:45

Ok.

Haden Guest 6:46

No?

Laura Huertas Millán 6:47

Okay. So, yes! Now it's working. [LAUGHS] So, in Jeny, the weaving, it's interesting because the film was born out of a mistake. Like, it was not intentional at first. On the first time, it was not intentional to link together, Jeny and the architecture. It was like circumstances and perhaps a sort of magic that was, that is present on the 16 millimeter itself. What happened is that Jeny was part of Black Sun, he's in the therapy group session. And so I met him, I will refer to him as him because he’s referring to himself in this way, so. So I met him during the shooting of Black Sun and I was very compelled about his story and the conversation that we had. So I wanted to come back and do a film with him. And it was the first time that I was using 16 millimeter and so I shot, I was shooting images and I put a roll on the camera. And so the roll just entangled inside of the camera. Yes. So it was a mistake. And so I went to a dark place, and took nervously out of the box and put it into darkness again. And at the same time, during those days, I was in Colombia, obviously. And my father asked me to make images of this building. He's actually a teacher in that university. And this building was an icon of left-wing student revolts. And my father was part of these movements when he was young. So he was very attached to this building and he was asking friends of him to do several records of this building before it was going to be demolished. And so I thought that the 16 millimeter was a good medium for this particular place and time. And without realizing, I took the roll that I was using with Jeny. And I didn't know. And so when the, I had two rolls, I guess? And when it came back from the lab, I just saw, like the, in editing camera, that I had done, and how it intertwine with Jeny. And yes, so I almost didn't touch, you know, it was an--

Haden Guest 9:25

[INAUDIBLE]

Laura Huertas Millán 9:26

Yes. And I found it was like this surrealistic approach of coincidences. Maybe it was not a coincidence. Maybe this was an inner desire that I couldn't express, or, so yes, it was out of a magical association. But this thing about associating, link, places and persons who are not at, that we wouldn't expect them to be together. This is something very important in my work, and it has to do a lot with mestizaje, and the fact of growing in between different cultures and trying to make sense of the contrast that I experience on a daily life basis, perhaps. So, yes.

Haden Guest 10:12

Hello?

Cecilia Barrioneuvo 10:13

[INAUDIBLE]

Haden Guest 10:15

[INAUDIBLE]

Cecilia Barrionuevo 10:25

Ole, ole. Ah, okay. Thank you so much, Haden. Thank you, Laura. I have a question because you were born in Colombia but you moved to France 18 years ago. And I would like to know, how is your vision of Colombia, if your vision of Colombia changed after you living in France? Do you think that the distance created another kind of approach to the daily life in your country or the reality in America Latina? And do you think you have done the same kind of films if you had stayed in Colombia? Because you took, you shoot this space, for example, before, and--

Laura Huertas Millán 11:09

Ah, now it's working. So, [LAUGHS] Probably not, actually, I wouldn't. I'm not sure I would make films if I had stayed in Colombia because I started doing films out of this situation of displacement and immigration. I was in art school at sculptures and I wanted to do sculpture and was trying very hard to make sculptures. But somehow it didn't make sense with my situation of having objects, or to store objects or, I mean, I didn't even have places to live, so it didn't make sense. So the moving image really came with this history of displacement and immigration and traveling a lot. So I'm not sure I have done films if I stayed in Colombia. And in Colombia, during when I was a child, cinema was such, it was very far away from my social background. Even in Colombia in that time, cinema was not, didn't have the cultural space that it has today. So it really, for me, cinema was like Hollywood. I had no idea I could do films. So yeah, definitely, it has to do with this history. And then, yes, having the chance of being in between countries definitely helped me to talk about situations that I had seen in Colombia and things that are very difficult when you live in, when you are inside Colombia, to make sense out of the violence that we experience, and the political situation. It's very hard when you are, like, in the country and you, and you cannot leave. So having the chance to actually being able to leave, to study what was going on, with a little bit of distance, definitely informed my films. And I feel like, nowadays, like the Colombian cinema community is not only inside Colombia but also outside Colombia. So many filmmakers like me, there's a sort of diaspora, yes, of Colombian filmmakers and I'm definitely part of that community.

Haden Guest 13:17

And then, but to talk about distance, this last film we see, Sol Negro, is, of course, a portrait of your aunt, in which– so this idea of you know, to follow up on Cecilia's question about filming Colombia or different, you know... But at this point, going even more, right? Even closer, and can you speak to us about this project, how it came about? This portrait of your aunt, which has incredible intimacy to it, that I think is really, in that almost final scene with a dinner with your mother, I think, is really quite extraordinary. I was wondering if you could tell us how the film was made and how you were able to really, get this really extraordinary intimacy and render it so vivid.

Laura Huertas Millán 14:07

Yeah, so there are different parts to the question, perhaps. Because it's true that I started working on that film after years of looking into anthropological images and having a very critical approach on ethnography and anthropology, as being very related to a process of colonialism, yes, and creating otherness in ways that I wasn't really, that I didn't agree, necessarily, with. And so, considering these practices, I have realized, or, yes, I noticed that anthropologists like to go to very faraway places and to the most exotic. And I actually did, before this, a series around exoticism. So, I was dealing with those questions, and at one point I asked myself what would happen if I try to go to the most intimate, to the most personal? And then this question was very complex because the most personal would be, so, the history of this branch of my family, where women, you know, there's this sort of thread of mental illness, gravitating all over us. And so it's something very present in the family. And at the same time, talking about this, when you have been 10 years abroad, with not a close relationship with the family anymore because precisely of that. So it was a sort of Pandora's Box that was opening. And I thought that the complexity of that situation was interesting. And it took me a long time to do the film. It took four years. And so the process was sometimes very chaotic and many times, I felt I couldn't finish the film or that it was very difficult to give shape to that intimate material. So I guess the project was already very intimate when it started. So the question was more, how to infuse a little bit of sense of distance. Because even living abroad, it was very visceral. And the project, actually, was developed a lot here. When I arrived to the Sensory Ethnography Lab as a Visiting Fellow, I had the idea already of doing this film. And I was writing the script, because the film is very fictionalized, I mean, I think it's a fiction. Yes. And so I developed the script here. And then I did a first shooting and came back here, and during a semester, I was showing incessantly, the cuts and versions of cuts to my colleagues. They, I think they suffered a lot [LAUGHS], suffered, watching me see suffering with that cut because it was so difficult to find the form. And then after that semester, I came back to Colombia and did a second shooting. The first shooting, I had like a cinema crew with 10 people, more, perhaps 20 people involved. And the second shooting, I was by myself. And I spent four months doing new images. And then it took another year to finish it with the help of a really great editor, Isabelle Manquillet, and giving shape to that, that material. So, yeah.

Haden Guest 17:36

When you say script, can you describe how, I mean, so the dialogue was also written by you? Or….

Laura Huertas Millán 17:45

Yes, so there was a form of, I would say, again, like an alchemy going on with the script, because I did several versions of the script, like imagining scenes. For example, when Antonia's sister is in front of the computer, imagining what would she say, looking at pictures, at photographs. So there was a, yeah! Really a script, with different scenes. But then I never gave the script to the actors, to none of them. And so we did a lot of rehearsal of each scene. But also, sometimes, because of this very intimate material, sometimes, even if we kind of rehearsed something, the scene would go in a completely different direction during the shooting itself. But yes, it was firstly scripted, and I mean, my aunt’s name is not Antonia, the Facebook page is fake, [it's a] false page. And yes, everything works on that level, I think. And to me, it was very important to use fiction exactly to that, to have a sense of a distance. I didn't want to do a personal diary or journal. I really needed fiction in order to be able to talk about this. Yes.

Cecilia Barrionuevo 19:06

In the film Sol Negro, when we can watch, the whole film, no? The fabulous, the wonderful voice of Antonia. The references to media, the empty stage, that is very strong, or, very, yes, this image, this scene. And the difficult motherhood that confronts the ideal model of motherhood, and all have a tragic meaning, most of the scenes, even when the tension between the center and the peripheries of the world is recognized. So for you, there are symbols or references that can be considered universal?

Laura Huertas Millán 19:53

Yes, I mean, I would feel in two different ways about this idea, this notion of something being universal. Because definitely, for a project like this, that comes from a yes, very intimate and personal place. There was definitely a huge effort in order to open space for somebody who's not from my family, or somebody who doesn't know me at all, to be able to get interested about this story, this character's trajectory, etc. So definitely, there was an effort to open this very intimate, enclosed space, in order to have viewers seeing this. And at the same time, yes, I'm very conflicted about this notion of universalism because it's a very Europe, it comes from a European history, and it has been a label in a lot of processes of colonization. For instance, when European travelers describe, like, indigenous communities in Latin America, when they arrived, they would say, these people are not, don't know, universalism. They don't have universal notions. So I'm very conflicted about that, yes, the idea of that something is universal because it means, from which point of view? Who is saying this is the norm, or who says this is normality, no? So, yes, definitely, that's a question that's running. But in the film, I like to play with some symbols that actually navigate between different cultures. For example, the Black Sun itself. Like it really comes from a French poet, Gerard de Nerval, who did a poem called “El Desdichado.” He was a Romantic poet. And in this poem, he talks about the Black Sun of melancholy. And so melancholy, it's very interesting because it really comes from an Occidental culture. It was like, the black bile for Ancient Greeks but then in Middle Age, it was also like a sort of power that artists or depressive people have, to get in communication with the cosmos, or artistic genius and inspiration. And, you see this symbol navigating, and in Colombia, romanticism is very present. Like you can feel drawn to that same kind of symbols, even if they don't come from inside the country. So yeah, I think the film navigates a little bit with all these influences coming from abroad, but that have been internalized in strange ways.

For example, when Antonia sings at the end of the film, it’s like, I don't know if you say this in English, or, in French we call that [?UNKNOWN?], It's a language, it sounds like English, or like German, or like French but actually it makes no sense. You see what I mean? Like when children in Colombia or in France, sing pop music and they're just doing as if they were speaking English but actually the words don't make sense? And if you look, if you listen carefully to the German that she's singing, it's an approximation, you know? It's, sometimes it's German, very precise, and sometimes it's something different. So I really like how these European models have been cannibalized, and digested and became something of a...

Cecilia Barrionuevo 23:42

Yes, and I don't remember exactly if your mother, or you, when you talk about Antonia, you said that she refers by herself in German, or she wrote in German in the Facebook, no? I think it’s…

Laura Huertas Millán 23:54

Yes. And, and I'm sure that this German that she uses is German, it's also a tongue of her own, you know, that she invented from…? So, yeah, I [INAUDIBLE].

Haden Guest 24:06

I mean, another way that you question this idea, I think, of universality, La Libertad. I mean, the very concept of this idea that freedom, La Libertad means something very, no? Different, or has a very particular sort of meaning for this community. And I found this really fascinating. I mean, it's not just work but also tradition, it’s also the sort of deeper history that you're finding within weaving, that we go back through the curators to see these older textiles. And so there's this idea that there’s this kind of, within a cultural tradition, there's a kind of freedom that, right? Perhaps. So I was wondering if you could talk about this, and then there's, of course, the assertion that being unmarried is a kind of freedom and we have the artist who’s also pursuing his own freedom to make these different, sort of highly sexualized, imagery. So, I was wondering if you could talk about the ways in which this film explores and expands and challenges ideas of liberty, of freedom.

Laura Huertas Millán 25:22

Yeah, so, it was interesting, because spending time with the Navarro family, in many of our conversations, the words “freedom” would comeback incessantly, like every time.

Haden Guest 25:33

It comes up in the film, right.

Laura Huertas Millán 25:35

Yes. And it was not something that I brought up. It was really something that was all the time present. And for me, it was surprising, because coming from this French critical background, so, freedom, it's a sort of, how do you say “trillado,” like almost a cliche word. Like, Paul Valery says, it's a word that sings a lot but actually means nothing at all. So, also watching politics, how they use “freedom” sometimes, or “we are going to do war because we need to teach people how to be free,” you know? This, to me, it's a very complicated word. And in our conversations with the family, it would come back all the time. And so I thought that it was not my role to judge if this was something that I was agreeing or not, but rather to try to develop, in a visual way, what they were telling me with that word and everything related to that particular word. And when I wanted to film these weaving processes, my interest was also in how these textiles can be considered as a parallel history or the archives of these colonial processes, but also these cultural exchanges that have been going on for more than 500 years. And how, if you consider the technique that they are using, and the fact that only women knew this technique for a long, long time, could we consider that these textiles are archives from a feminine point of view, of these processes of intercultural exchange and colonization? And actually, the technique that they use, the backstrap loom, is a technique that has survived since before the arrival of the Spanish people until today, because women had teach this technique to their daughters, to the, so it's really something that comes from the feminine world. And so, yeah, thinking, perhaps related to that thread of freedom, I was thinking about how women have preserved a parallel archive, a parallel memory. And it has to do with a sort of a procession running in all of my works, which is how history, history or herstory, you know, what kind of narratives we have about time passing and who gets to write those and, you know, the circulation of that.

Haden Guest 28:27

So also, this idea of being free from the sort of colonial history, then, too, right? This idea that this is an indigenous– and I mean, I love this kind of lexicon of different animals and symbols that are recorded on the cloth, that one of the weavers is saying, so there's a kind of, a refashioning of Greek coins, and things like this, into different shapes.

Laura Huertas Millán 28:55

Yeah, and at the same time, I don't think we get to be free of that story, or to be liberated from that story. Somehow, there's a sense of negotiation also, and of cultural exchange. Like when you see all the figures in every weaving, some of those figures can come from a very ancient times and some others are very contemporary. Or when you see the threads they use, like the colors of the textiles, some of them are very industrial, some other are organic, you know? So there's really this sense of mestizaje, again.

Cecilia Barrionuevo 29:36

Yeah, when the woman showed this belt, this faja, and enumerate all the animals and the objects that appear and through no sense, no? It's a kind of poetry, or seems poetry, in some point. But profound themes, such as conquest, syncretism and the tradition are revealed in this moment. I would like to know if, how did you make, to find, or to shoot this kind of moment? How do you look for them?

Laura Huertas Millán 30:12

Yes, I think there's definitely a mise-en-scene in those moments because they're not spontaneous, at all. It comes from a certain sense of repeating things. When I'm shooting or doing a film, repetition is very important in my process and things that perhaps we experience as a viewer, as a testimony, are actually things that we have been rehearsing a lot. And I like the factthat something that comes from reality out of repetition, or rehearsals, enters a space of oral transmission. And this is something that in Colombia is very important, that the history, as we know, is not only the written history. It's also the oral tradition coming from indigenous communities or for communities. They didn't have access, actually, to the written archives and written displays, you know? So, yeah, so this sense of repetition and with speech is definitely a mise-en-scene, yes, definitely, rehearsal and work. And that is, perhaps, how it gets a certain perfume of being poetical. Yes.

Haden Guest 31:35

But in Sol Negro, there's also the idea of the therapeutic, no? This idea that this telling, again, of these intimate stories, can reveal something, it can open up a different kind of emotional, perhaps, healing? And begin, though, with this breathing exercise, to... I feel like, and then end with the song. It's as if, searching for a way, like language that's repeated, or it's sung, as in the rap song. It's trying to loosen, I think, language from the sort of strict shackles of, no? Of, alright, let’s just say, inherited use. And looking for something, no? A different kind of mode of communication, or you could say, looking for the poetic, perhaps? And I was wondering if that's something you could sort of expand, or think. I'm reaching for something here, ’cause I feel like this is something, that the ways in which, you know, the therapeutic sessions, the ways in which the communication is shared by the weavers, the ways in which Jeny, telling his story, like, to you, and again, there's a kind of repetition, a shared communion and communication, that somehow brings about a different kind of intimacy, or revelation, or...?

Laura Huertas Millán 33:02

Yes, that definitely a space for language to be embodied and to be... or perhaps of situations of empowerment related to language. Perhaps because these different contexts of each one of the films are contexts in which language, for a lot of it, has been imposed somehow by taxonomies and fixed identities. For example, in Black Sun, I was very conscious that the film was going to deal with something related to mental illness and bipolar disorder, etc. But I didn't want the film to be an illustration of that taxonomy. You know? I wanted the film to be able to create spaces to tell ourselves in a different manner and not just having this label, or this fixed identity. I wanted to complexify that space. And this is something very present in all of my work. That's why I talk about something that's a situation that will allow us to be empowered towards language because we can manipulate it and make it something of our own and find space, new spaces of enunciation. Yes.

Cecilia Barrionuevo 34:34

This is, that you say, it is interesting because in your film, you delve into the truth place, not only in the character, but also in the spectators, when, to construct a discourse, and perhaps, in the way, to break with the hegemony of the official stories, no? You break with that. On the other hand, the relationship of tension between what is seen and what is heard and what appear and what not appear, or it's just, yes, simulated, or you think that is, or not, is very present in your work. It is a reflexive space for our spectators. And do you pretend to questioning the public, or to, yes, are you interested in questioning the public with your films?

Laura Huertas Millán 35:29

Yes, I don't know if questioning but I definitely, as a spectator, I appreciate when films give me space to... films that make me feel empowered, in the same way. Like films that don't impose me a message, or one single direction but films that really allow me to wander and even physically, mentally wandering in it and find my own way through them. So I try to build those spaces that are complex enough, so that it's open enough for anyone to enter it and find your own way through it. Of course, given elements of comprehension, otherwise you can really get lost. But yes, I try to, yes, when we were talking about freedom, I think it's very related to that because I don't think that freedom is something that you impose to others. It’s not something, you don't tell somebody, you have to be like this, and this, and this is to be free. It's something else, it's about sharing a space together and responsibility, shared responsibilities. So yeah, I try that this thing that I'm looking for, during the shooting, extends to the finished film, as much as it is possible.

Cecilia Barrionuevo 36:58

Yes, is maybe through the language and through the distance or the proximity between the language and, I don't know, the relation between the hegemony of the discussion that you propose and [what] a spectator gives to the films, no? This relationship constructs another kind of truth of the world. Maybe broke with the hegemony or Eurocentrist or works in the sense of the decolonialism, probably. I don’t know.

Laura Huertas Millán 37:35

Yes, I don't know. I always feel conflicted about this word, the “truth.” A lot of artists talk about art in terms of searching for the truth. But most of the time, I don't feel that way. I feel that I try to structure a huge confusion and I don't think that films get me truth in return but they allow me to give sense to something that is chaotic and that makes me feel like a victim, perhaps, or it's too overwhelming? And so the film is really the space of trying to give meaning to things. So yeah, I would prefer, perhaps, meaning, and not, yes, truth, I'm not sure. Maybe there's a sense of, instead of truth, there's something that I look for, even though I use fiction or try to fictionalize some things, is more the idea of reality, or something that is, yes. You know, it's a little bit like when you have an accident, for example. And for 10 seconds, you feel reality in such an intense way. And sometimes in the shootings, it's this kind of real intensity is something that I look for, and I try to give space to that in the films, too.

Haden Guest 39:02

I mean, we've talked quite a bit about language. And I wondered if you could talk about– because you talked about embodiment of language, but the body itself is so important in your films, and the ways—in La Libertad, we have these wonderful close-ups of hand and feet, and this idea that this passed-on tradition, this, of weaving is a kind of, no? Like gestural language itself. There's a moment in Sol Negro where we have the cooking, and where we see the hands, and there’s this also, sense, that there's another sort of, communion and community, right here, in the most intimate kind here around the ritual and practice of cooking. And then with Jeny, as well, his preparations as a kind of gestural practice, as well. And I was wondering, if this is something you could also speak about, a little. You know, just in thinking about your interest in this kind of close-up, this kind of fixity on the body, ’cause, you know, you included this wonderful film by Chick Strand last night, Artificial Paradise, and I know that her work is really important. I think about the ways she also focuses on the body, as, no? As such a central, sort of expressive force in her films.

Laura Huertas Millán 40:21

Yes. Yes, La Libertad was actually shot after Black Sun. And I think this close-up thing really came during Black Sun. It was, to me, something related to the body of the main character, which I was really struggling for ways to represent her, in a way that could be beautiful but it was not just a superficial, you know, take on beauty but really that she could feel comfortable with the images that she, she was giving to me. And somehow, also, this close-up was a way to almost have, like a microscope, and make a search for, for expressions that perhaps, would appear too ordinary, or too daily life-related, if they were not, like, monumentalized. So I think there's something about this searching of something from everyday life that needs to become visible for others. And so the close shots really came like a way of putting a microscope into something that could otherwise be very banal. Yes.

And in La Libertad, it was, I was trying to develop [this further]. And it was interesting, because I shot La Libertad after a semester here, and I was very willing to experiment with a moving camera and body camera and you know, to be close, or do this sort of choreography. But then, after weeks of shooting, I just realized that the closeness that I was getting with this sort of performative, action/body thing, it was actually not very genuine, it was more like a sort of performance. And in that extent, it was too much on myself and not in the space that we were sharing. And so at one point, I started to do still images again, like putting the tripod and to think about the close shot, not in terms of being close to somebody but more in terms of depth of field, to have, really to extract, to cut a piece of reality, and have a very thin depth of field. So yes, I think, in Chick Strand, it's very interesting because I didn't see her films before doing La Libertad or even doing Sol Negro. It was afterwards, I saw her films here and I was amazed how close they were to the question that I was asking myself and also the how she films groups of people. In Fake Fruit Factory, for example, when she films the bodies in the swimming pool and you have the impression that they constitute one single body made of different parts, you know? And yes, to me, that's very interesting, about how she's always creating a body out of every single detail, no?

Haden Guest 43:36

Maybe we could take some questions from the audience, if we have a microphone on both sides. If you have a question or comment, please raise your hand. We have one in the very back. Right there, that's fine.

Audience 43:51

Hi, Laura. Thank you for this beautiful program. I was very surprised, partly ’cause I don't usually look at it, but that your films are on MUBI. And I thought that was kind of amazing. That, for me brings up the question: Haden commented that your films are not academic. “Thank God” seemed to be in parentheses. But here we are in an academic institution. So I'm curious about how, because you spoke a little bit about spectatorship, how would you like your films to be seen? And how are they seen, both in Colombia and in Europe?

Laura Huertas Millán 44:30

Well, yeah. I'm very happy about the MUBI screening, still two, three days, if you want to tell your friends to watch them, they can still do it. I'm very happy about it because yeah, growing up in Colombia, like all the relationships that I had with cinema was not really going to cinema. It was not something that was part of our daily lives. It was something very distant. And all of the films that I got to see when I was a teenager were pirate films, like pirate DVDs, really bad VHS copies, films broadcasted on TV at 2 A.M. in the morning. So, you know, the sort of relationship with media was kind of different. I was not raised in this sort of context toward cinema. But then I feel like academia has given me so much. All my immigration story is related to the history of, to the fact of being a student. Being a student, also, I was able to stay in France and to make another kind of living for myself. So I definitely, I don't create films just for academics, even though they have been developed and conceived and imagined in this context, and having the chance to have discussions with very smart people, and very critical, and very demanding people. So, yes, my ideal, or my fantasy is that I create films for everybody and I'm very happy to be able to screen films outside of film festivals, even if they're great, but you know, to get to have other audiences to see the films, it's very important for me. And at the same time, I'm very conscious that these spaces where you can actually meet other kinds of audiences, there are not that many of them. You can count them with your hands. You know, there are few of them. So, I don't know. Sometimes I feel that it's really nice to be pirate. You know, to have your films on the dark web, or whatever, and people have access to that and you don't really control it. I am happy about this. Because I feel that people that wouldn't have access to this sort of screenings, can see the films. Although I feel very lucky that we do have these spaces, right? Because academia also allows practices that are non-commercial to develop. And so, I really feel that I still have a part of myself which is related to academia. I’m grateful to that.

Haden Guest 47:29

I do want to emphasize the role, I think, of film festivals today, has become so incredibly important. The festivals like Mar del Plata, like the Biennale, they like Film Marseille, where Sol Negro was premiered. And I feel like that's really such a vital place today for this kind of difficult-to-classify film to really, I think, to flourish, and to thrive. I think more so than at any other moment, I think.

Laura Huertas Millán 47:58

Yes. Yes. And it's interesting, for example, Film Marseille, or what Mar del Plata does, the fact that you really show films that are non-traditional narratives, experimental films, people who take risk doing the films and the audience coming, is audiences from very different backgrounds, right? Yes?

Cecilia Barrionuevo 48:20

Yeah, particularly when am I thinking about Mar del Plata. The audience, it's just normal public. There are cinephiles and students but the people of the city or people of the other parts of the Argentina, or Latin America, arrive to the festival, just audiences that are very interested in [knowing] the work of the filmmakers that are more [hidden], and not in the supervised, probably, of the, yeah?

Laura Huertas Millán 48:53

Also, somehow it's can, it's also political, right, too. Because sometimes we see that there's this populist idea that culture needs to be accessible to everyone. So this would mean that it has to have a low quality level. But I believe these places prove something very different. That you can still have a huge audience, and propose quality content, complexity.

Haden Guest 49:21

Absolutely. Let's, are there other questions, comments? We'll take a question from the back, please?

Audience 49:38

Hello. In all your films, you do not pan to tell your story from the past and the present. Can you explain more about that? Is that your style? Is that in all your films?

Haden Guest 49:58

Absence of panning [?UNKNOWN SPANISH PHRASE?].

Audience 50:00

Yeah.

Laura Huertas Millán 50:02

Yes. In some other films, I have pans but not in these ones because I felt it was not pertinent, you say? Germane? Yes. Appropriate for the content of what I was trying to convey. Yeah, I think every single form that you see in the film is the result of an experience, of the experience of the shooting but also the experience of thinking about how this particular story can be told and from which perspective it is being told. So something that is present in all the films is that I'm not trying to put the attention of the viewer on the performance of the camera, or how this shot, shoot is so complicated to do, or how I needed, like, a lot of machines to do this sort of movement. This was not something that I want, I didn't want people to focus on the device, on the mechanical device. I really wanted the emotional content and the presences of the bodies to be the protagonist.

Haden Guest 51:19

I just wanted to follow up on one point... but at the same time, you have, especially in La Libertad, such meticulous mise-en-scene, which does, in fact, draw attention to the constructedness of the image, as well. And I was wondering if you could talk about, perhaps, the tension in that sense, of the film. I don't want to say, drawing attention to itself. But there is a sense where we really admire the beauty of the compositions, and the kind of almost abstract art that you discover within the weaving.

Laura Huertas Millán 51:55

Yes, I mean, this idea of—it's a real necessity—mise-en-scene. I'm not trying to do an objective take on a particular reality, I'm trying to articulate something. So there's–

Haden Guest 52:10

Your investment in it. There’s again, this..

Laura Huertas Millán 52:12

Exactly.

Haden Guest 52:12

...search for the poetic tension, if you will.

Laura Huertas Millán 52:17

And that's why I wouldn't have the pretension to call these films documentaries. But I'd prefer even if, perhaps, it sounds more pretentious, I don't know. But I prefer “ethnographic fictions,” because it's really about getting into an immersive presence within a community but then trying to, as you say, to articulate something that can look very constructed and very mise-en-scene.

Haden Guest 52:49

Okay, any…

Cecilia Barrionuevo 52:50

Most of the– I’m so sorry.

Haden Guest 52:51

Oh, please!

Cecilia Barrionuevo 52:52

Just one question because your film, most of Sol Negro and La Libertad, I feel that they are very feminist films. And in some point, seems that you or your character, with the films tries to construct or to build another kind of history or another part of the history out of the feminine point of view. In this sense, I thought, what do you feel about the feminism in Colombia, the feminism here in America, where you studied or the feminists in France, where you are living now?

Laura Huertas Millán 53:33

Yes. I have a lot of mixed feelings [LAUGHS] about these different sorts of.. Definitely, there are many different types of feminisms, right? And with time, I have got to identify it more with intersectional feminisms, and decolonial feminisms. And we were talking about freedom. It has to do with this, because in France, you have a branch of the feminism which is universalist. So it's French feminists, explaining to women from the global South, how they should dress, what they should do to be free. And I definitely don't agree with this. I feel that it feeds, actually, nationalism and all the extreme right-wing, and problems that we are living right now come from that perspective. So, yes, I feel closer to approaches, which really consider that it's not your role to tell other people from different context, how to behave and what it is to be free. And in my films, I don't know, I think somehow this works, a lot. For instance, with the Navarro family, the fact that I was more trying to build a space where we could share things and questions. And I was not trying to say, oh, so I agree, or not, with their view on freedom. It's not my role. I'm just trying to weave what I'm seeing and the discourse that is being produced around these objects. Yes. And in Sol Negro, there was also the sense that in the Colombian context, everything related to war, it has been also told a lot from the perspective of men. But I feel that we still have a lot of work to do with what is going on in the female or female-identified bodies. And all this violence has had a lot of impact in them. So in Black Sun, I was trying to touch with the tip of my fingers that question, how the most intimate is actually also the reflection of a very long history of violence. And during the dinner scene, that was going on somehow. Like, at one point, Antonia’s sister says it literally, like, I mean, of course we are mentally ill, it's impossible we are not distressed by all these generations and generations of violence. So, yes, and in La Libertad there was something similar. So, how women, or again, female-identified bodies, have lived all this history. And I am definitely eager to put my camera towards that side.

Haden Guest 56:42

Well, I want to ask you to join me in thanking Laura Huertas Millán and Cecilia Barrionuevo for their presence here tonight.

[APPLAUSE]

Cecilia Barrionevo 56:51

Thank you Haden. Thank you Laura.

Laura Huertas Millán 56:51

Thank you.

[APPLAUSE]

©Harvard Film Archive

Related film series

Explore more conversations

Whit Stillman

Paolo Gioli

Kelly Reichardt

Alexandra Vasile