Sorcerer introduction and post-screening discussion with Haden Guest and William Friedkin.

Transcript

John Quackenbush 0:00

September 26, 2014, the Harvard Film Archive screened Sorcerer. This is the audio recording of the introduction and the Q&A that followed. Participating is HFA Director Haden Guest and filmmaker William Friedkin.

Haden Guest 0:18

Good evening ladies and gentlemen, my name is Haden Guest. I'm Director of the Harvard Film Archive. Before we begin, I'd like to ask everybody please turn off any cell phones, electronic devices that you have and please refrain from using them in tonight's screening.

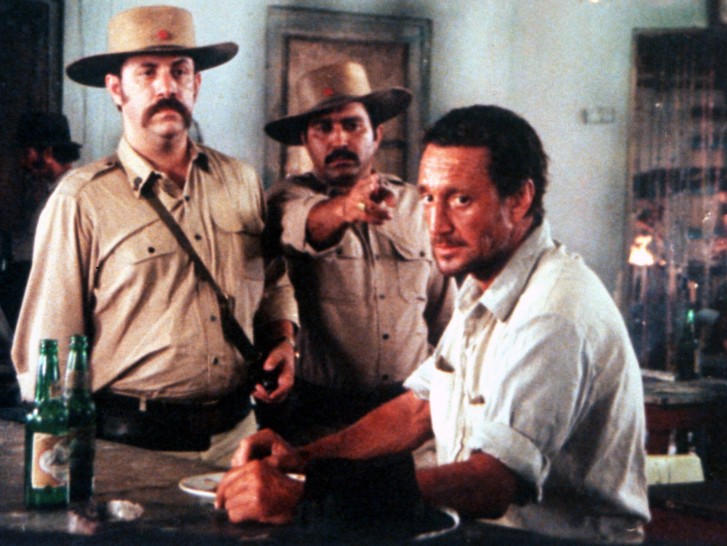

Tonight, we welcome one of the true legends of the American cinema, William Friedkin. Friedkin is one of the towering figures who transformed Hollywood cinema in the 1970s and helped invent what was called the New Hollywood with films such as The Exorcist, The French Connection, and tonight's masterpiece, Sorcerer from 1977. When we see a film by William Friedkin, I think we're tempted to say “They don't make them like they used to.” Fortunately, Mr. Friedkin still makes them and he made me a really marvelous and unbridled and no holds barred Southern Gothic thriller with extraordinary twists, Killer Joe, which we're going to be seeing tomorrow night.

[APPLAUSE]

Thank you. A film which is already considered a classic. The rerelease of Sorcerer earlier this year was hailed as one of the film events of the year. The film, which was originally released on 35 millimeter, was remastered digitally and rereleased on DCP, which is what we will see tonight. And this film, I think, is part of a larger reappraisal of William Friedkin’s films and legacy. And this is a reappraisal that has really been driven, I think, in large part by a wonderful memoir, which Mr. Friedkin wrote in 2013, which I highly encourage you all to read if you have any interest in American cinema. In one of its great visionary talents. It's called The Friedkin Connection. This book, which I think is remarkable for its candor and for its really striking prose, and for its insights into film production, into, again, this Golden Age of Hollywood cinema. This book is very important to us now here at Harvard, because earlier this afternoon, we had the great honor to receive at Houghton Library, as a gift from Mr. Friedkin, the original manuscripts and audio recordings for this book. So we have a William Friedkin Collection here at Harvard now. This gift also comes together with a very generous donation of exhibition prints of Friedkin’s classic films. So we're absolutely thrilled and honored to welcome back William Friedkin for these two evenings of screenings, but also, to receive this remarkable gift. To receive the gift here, officially, is Sarah Thomas, who is the Vice President of the Harvard Library. Please join me in welcoming Sarah Thomas.

[APPLAUSE] 3:30

Sarah Thomas 3:40

Thank you. Well, it's just a huge pleasure to be standing here and to have earlier today, have been in Houghton Library with William Friedkin and Sherry Lansing and looking at the manuscript of this wonderful Friedkin Connection. You should know that– How many of you...? Well, maybe I shouldn't ask that, but I hope you'll come and visit the Houghton Library.

[LAUGHTER]

So we won’t ask how many have been there already. But, guess what? It contains twice as much stuff as is in the published book. So any of you who are really serious about film, you'll want to be coming over to Houghton, and seeing what's going on. And the thing that is also very wonderful, you've heard Haden tonight, is that the Harvard Film Archive is a part of the Harvard Library. So we're bookended with the Houghton Library, with some of our greatest treasures, and then here, cutting edge activity in the visual medium. So it's really wonderful to have that come together. And I want to end—before William Friedkin comes down here himself—to say I had the pleasure, about a decade ago, of having breakfast with Toni Morrison, the Nobel Laureate for Literature. And someone was asking her about students and writing the Great American Novel. And she said, “Students today, they want to make the great American film.” And isn't it wonderful that we have William Friedkin here today, who has made not one, but several great American films. Thank you very much.

[APPLAUSE]

Haden Guest 5:32

I just wanted to give a very special welcome, not only to William Friedkin, but also to Sherry Lansing, who's joining us as well. Please give me a round of applause. Sherry Lansing.

[APPLAUSE]

Another legend of the American cinema. And now, with no further ado, please join me in welcoming William Friedkin.

[APPLAUSE]

William Friedkin 6:07

Hello! Thank you very much. Thank you. Thank you very much. It doesn't get better than that. So I'll see you later.

[LAUGHTER]

What a thrill it was to see this Houghton Library today. You guys remember books, don't you? You know that you could hold in your hand paper and bindings and stuff. They've got everything. There’s a whole room dedicated to all of John Keats's works. You know, the original publications and stuff. And manuscripts that I saw written by the hand of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Emily Dickinson and Theodore Roosevelt. You guys know what's there. To have my book there is a tremendous honor. I can't think of a more meaningful honor than that. I never went to college. I barely graduated from high school. But I always knew, I guess by osmosis, that Harvard was the best university in the country, if not the world. And it's what I would have aspired to, if I hadn't been such an idiot when I was a kid.

[LAUGHTER]

But with my memoir, I actually set out to write a sequel to Madame Bovary. And I wound up with that book instead, The Friedkin Connection. So, The Friedkin Connection, c'est moi, to paraphrase Mr. Flaubert. A lot of what I discuss in my memoir has to do with events that are taking place today in Iraq, because I lived in Mosul, up in the northern part of Iraq, for three months in 1973. And it was before Saddam Hussein. It was still the Ba‘athist Party. The president was a guy called Hassan al-Bakr. And I actually lived among the Kurds, and spent a lot of time with the Yazidi, who have become very well known recently for having been trapped on a mountaintop by ISIS. What you don't read a lot about in the accounts of the Yazidi is that there are many tribes of Yazidi in that part of the world, but the one in Iraq, they are the devil worshippers. And I actually was summoned to a meeting with the sheikh, who was the head of the Yazidi tribe then. And we had erected in the Iraqi desert, in Nineveh, we had erected a replica of the statue of the demon Pazuzu, which is like a fourth century Assyrian statue. Those of you who've seen The Exorcist will know who Pazuzu is. He made his presence felt for many years as a result of that film. But the original is in The British Museum. There's a beautiful bronze of it that I saw the other day in New York, at The Metropolitan Museum.

But in 2003, I was invited to go back to Mosul by Lieutenant Colonel —then Lieutenant Colonel—David Petraeus, who had entered Mosul with the 101st Airborne when we invaded Iraq to unseat Saddam. And he invited me to come back to Mosul because, he said, the people there remembered me and they remembered the shooting of the film. And in this most historic of places in the world, the students at Mosul University set up a thing called “The Exorcist Experience.” For which they charge one dinar, and another dinar if you wanted a kebab.

[LAUGHTER]

And they cleared a parking lot. And he said it was the members of the 101st Airborne had donated $5,000 to set this up. And it was a big success. And he had arranged for me to go back to Mosul; bring some Blu-rays, or DVDs at that time. And to see again those people who are alive, and there weren't many, from the time that I was there. I agreed to go back, you know, the next day. It kept getting postponed and postponed. And finally, I got a telegram from his adjutant, saying “It's too dangerous for you to come.” And Mosul, then shortly afterwards, and until this day, became the home of the Al Qaeda in Iraq.

But the people that I met, I would have to say, I have never felt closer to a people in my life. And I've been all over the world. And in those days, in those times, just before Saddam, women were not oppressed. They did not have to wear a burqa, except to go to a mosque. They were in all the professions. They were doctors, lawyers, teachers. They did everything. And it was a beautiful, peaceful atmosphere in the middle of some of the most historic biblical sites that exist. And I write a lot about that in my book, and a lot of other things as well. When Harvard accepted my book for the Houghton Library, I was thrilled beyond belief, because I now know that it will be preserved in what is arguably the best library in this country. So I want to thank Sarah Thomas and Leslie, and Haden Guest and David [Pendleton], Leslie Morris, who is the curator, and Sarah Thomas for inviting me to come and participate in the ceremony. And again, to Haden and David, for running this particular film. If this is the only film of mine that survives, long after I'm gone—and by the way, I passed my sell-through date, according to Dr. Ezekiel Emanuel, who quite recently wrote in The Atlantic Monthly, that by the age of 75, we should all be dead. Because, “of what use, are we to society?” I guess he's never heard of Stravinsky or Louis Armstrong, I don't know. But I've passed that sell-through date. But if none of my films survive at all, except this one, I'm a happy person. Because I don't really have favorites. I can't tell you what my favorite film is. It's probably Citizen Kane, but I don't, you know, make a big issue about that.

[LAUGHTER]

I almost directed Citizen Kane, but Orson Welles got the job.

[LAUGHTER]

But... son of a bitch.

[LAUGHTER AND APPLAUSE]

But this is the film that I hope to be remembered for. And I don't think in those terms. I do not think of myself as an artist. I think of myself as a working stiff, who just happens to be fortunate enough, and by the grace of God, to be able to make films, which is the art form of the 20th century. And Sorcerer is the only film that I made– I think in 50 years I only made about 15 films. But this one tonight is the only one where I came closest to the vision that I had of the film, before I made it. I can still watch it. I could sit out here tonight, if there were any seats.

[LAUGHTER]

I came here, I guess, in 2009, where Haden ran the film in 35 millimeter. Were any of you here then? Probably not. One person. You must have been a child. Were you? How old were you? Oh, really? Well, you were a child at– He was 35. He was a child at heart.

[LAUGHTER]

But this is the digital video, and it's not a video. It's the digital cinema print. And to me, it's the absolutely best form with which to preserve film. Now, I don't know how it's gonna look here tonight, but it took me four months to make this print. And this is the very best print of the film that was ever made. We could never achieve perfection in 35 millimeter. You always had the problem of the developer, which would change constantly, because of the makeup of the amoeba in the water. You would have fluctuating electricity to the printer. And so there wasn't one reel of one film of mine, or anyone else's in the era of 35, that was exactly what the filmmaker wanted to do with the color. For example, you could fix one portion. The entire portion of the screen, you could make it bluer or warmer or whatever. But you could not go in and restore the interior subtleties of the color. With digital, you can. And we did. This digital print looks exactly as it looked to me when I made each shot, looking through the lens of the camera. So I really am pleased that Haden and David and the Harvard Archive are running the film again tonight. I'm going to stop by afterward and answer any questions that you might have.

How many have seen this film? How many of you have seen it? That's not too bad. Well, this is the best looking picture of it that you will ever see. They ran it at The Brattle, a month or so ago, I believe. And there's a gentleman here tonight, who wrote a really excellent and insightful review of it in The Boston Globe, named Peter Keough, who's here tonight. And I want to welcome Mr.—Peter, where are you? In the back over there. This guy is a really great—stand up Peter.

[APPLAUSE]

Stand up Peter, let him... Thank you. I'll tell you how much I love this film. Mr. Keough has seen and reviewed the film, and he's back here tonight.

[LAUGHTER]

So that tells you something. And listen, I can't go back and look at all my films again. I just can't do it. It would be sheer torture. I would prefer a new edition of the Spanish Inquisition, than to have to go back and look at some of the films that I made. But not this one. Thank you all for being here tonight. I'm really pleased to be here. God bless you, thank you.

[APPLAUSE]

John Quackenbush 19:19

And now the discussion with William Friedkin and Haden Guest.

William Friedkin 19:53

What can I say? I'm so grateful that you saw the film this way. Thank you very much.

Haden Guest 20:02

Well, Billy, I thought maybe I’d begin with a few questions before taking them from the audience. In 1977, you just made two incredibly, commercially and critically, successful films: The Exorcist, The French Connection. You could basically, seemingly, make whatever film you wanted to. And you chose to make what I would consider one of the greatest... not only one of the greatest films of your career, but, I think, also one of the greatest remakes ever, returning to The Wages of Fear by Henri-Georges Clouzot and its source novel by George Arnaud. And I was wondering if you could speak about what drew you to this project. What drew you to The Wages of Fear, and what it was that you saw there as the potential for your next project?

William Friedkin 20:56

Why don't I take this and I’ll move around a little.

Haden Guest 20:58

Absolutely. You’re the director.

[LAUGHTER]

William Friedkin 21:02

We’ll see how much of this I have.

Haden Guest 21:06

There you go.

William Friedkin 21:07

That's not bad.

Well, after I made The Exorcist I think I spent almost three years working on all the foreign versions of The Exorcist.

[LAUGHTER]

William Friedkin 21:19

Literally. I hired directors. We made three foreign language versions. We made Italian, German and French versions. And I hired three directors to direct them. I hired the writers to write the scripts and translate them. One of the writers—the guy who wrote the French translation—was Jean Anouilh, you know, one of the great playwrights of his time, and among the directors was, oh, the German director who did The Bridge. And he was in the Antonioni film, La Notte. Anyway, he's in his own right– And I hired Fernando Rey, who was in The French Connection, to do the Spanish translation. But for the dubbed versions, each of the directors sent me voice tapes—audition tapes—and I chose the actors who dubbed the film in those various languages. I also worked with a translator on the Japanese subtitles, because that really needed to be carefully done. Because there were no really swear words in Japanese. I mean, the worst thing you could call somebody was a fool, you know. So we had to do some very careful translation there. And I worked on all of those translations and subtitling for close to three years. And I went around the world making sure the prints were good. In fact, the first 26 prints of The Exorcist, which ran for six months, I supervised each one of those prints. And I had the phone numbers and the names of all the projectionists in the 26 theaters. And I went to each of the theaters and set the sound level and the picture level, brightness. Because a lot of theaters would —and still do—turn down the brightness to save electricity. And I went in– I had the names of all those guys, and The Exorcist ran in first-run for about a year. It went from 26 theaters to 50, and ran like that for a year. And I would call each of the projectionists every week. I'd call eight, one night, and five the next night. And I would check on how it was playing. And one of the projectionists would say to me, “Well, reel seven is damaged, Mr. Friedkin. We had a tear.” So I sent him a new reel seven. And I really watched the release of The Exorcist as though it was a play. And I didn't do anything else. And one day I remember having lunch with Wally Green, who wrote this script. Wally had also written The Wild Bunch. And he and I work together doing documentary films at Wolper Productions. And we sat around talking. I had no idea what I wanted to do. It was at least three and a half or four years after the release of The Exorcist. And in a conversation we said, “You know, let's do a film that's like Treasure of Sierra Madre and The Wages of Fear,” because I felt, especially, that The Wages of Fear was relevant. And still is. The idea of four strangers, who basically hate each other, but have to work together or die, seemed to me to be a metaphor for the world situation, then and now. And we also decided, because as you said, I had a lot of leeway because of The Exorcist and The French Connection. I could do basically, you know, my nephew's Bar Mitzvah if I wanted–

[LAUGHTER]

–as my next film. But I thought not of making this as a remake, because only the basic storyline is similar. All of the events and the characters are different. And I went to H.G. Clouzot before I did this film, and got his approval. And in fact, he didn't own the rights. The writer of the novel owned the rights. Georges Arnaud. And they didn't get along. So we really got permission from Arnaud to make the film. And I thought of it as a completely original take on a classic idea. Like doing another production of Hamlet. You know, it's not a remake of Hamlet. You know, the first one was done in about 1601 or 1603, or something. You would know that here, certainly.

[LAUGHTER]

But, you know, there’ve been millions of productions of Hamlet and they're not called remakes. I mean, the film Casablanca was actually a remake of another film. And it was a play! Casablanca was a play first that didn't even run on Broadway. But the one that we remember is, you know, that one. So it was rather arbitrary, my choice. I thought I wanted to do something relevant. The Exorcist had, for the most part, been shot in one house, and in one room. Most of it. Aside from the prologue and a few other scenes. But the last, like, third of the film is in the house and in the little girl's bedroom. So I certainly wanted to break loose from that. And so it was a totally arbitrary decision to do that. I didn't even consider anything else. And I didn't know if I would ever make another film after The Exorcist, because it was a shell-shocking experience. The way the film was received, you know. It was like an international scandal. And very popular, of course, but very controversial. And very hard edged. It had certainly gone where most other American films had never gone. I never saw that coming. You know, to me, it was just a great story that I tried to tell realistically. And when it came out and exploded the way it did, and had people fainting and throwing up and stuff like that. I was quite shocked to see that, because when you make a film, you make one shot at a time. That's all you think of. It's like knitting. Have any of you gentlemen ever knitted?

[LAUGHTER]

Well knitting—you know, it's knit one, purl two, knit one. That's how shooting a film is. That's the best way I can describe it. One shot, or one stitch, at a time. And you have to see the whole in the same way that someone knitting has to envision the whole sweater, or the pair of socks, while they're doing it one stitch at a time. You have to envision... you have to have the entire film in your head. And if I don't, I don't make the film. I've started a lot of films and abandoned them, because I couldn't see them in my mind's eye. This one I could see, and as I told you when we started, this is the one that came closest to my vision of it.

Haden Guest 30:07

I mean, formally, one of the things that I admire so much about the film— you speaking about it, you know, shot by shot, stitch by stitch—is the editing of the film and the way in which these sequences—and we were talking about this a little bit, earlier—the way in which, oftentimes, there’s this radical cut, like from, you know, from the second bridge sequence to suddenly the daytime, in the jungle. Like, you know, this choir of sequences. It's these radical cuts from night and day. From one soundscape to another. From Jerusalem to Paris to, you know, New Jersey. I was wondering if you could speak about this idea of not simply having four different stories, not necessarily intertwining them, but actually, sometimes, like breaking the sort of continuity between them, creating something that's jarring and, at times, disorienting.

Well, the strongest influence on me when I was young was dramatic radio. Do any of you remember dramatic radio? You know, radio?

[LAUGHTER]

No inch television. Where you had to use your imagination. And then were great radio programs. Incredible dramas on the radio that used sound and music and the human voice. Orson Welles was one of those great creators who brought the technique of radio into cinema, the way he used sound. And, of course, I may have mentioned, or you might have heard, that Welles was a profound influence on my work. I mean, I don't ever expect to make a film that can be used in the same sentence as Citizen Kane, but that film is a virtual textbook, you know. As some great literature becomes a textbook for writers, that's what Welles was to me, and dramatic radio. But my first encounter with Wells was on radio. He had the Mercury Theater on the air, and he did the voice of The Shadow. And all of his radio programs had distinctive use of sound. And I regard the soundtrack, to this day, as a completely separate creative process than shooting the film. It's totally different. It's running along in sync, you know, but it's a different process completely to me. And it's the most interesting process. The sound.

Haden Guest 32:55

I mean, speaking of great literature, in your wonderful memoir, in the chapter on Sorcerer, you mentioned the importance of Gabriel García Márquez as a kind of inspiration as you were scouting the locations in Ecuador, and Dominican Republic. Eventually in Mexico. And Marquez comes up, as well, I think, throughout your later films. You mentioned, as well, To Live and Die in L.A. I was wondering if you could speak about García Márquez in the context of this film and, perhaps, in the context of your thinking about narrative.

William Friedkin 33:33

Well, of course, arguably one of the greatest novels of our time is Cien años de soledad. One Hundred Years of Solitude. Márquez did not introduce magic realism. That was probably a Mexican writer, Juan Rulfo, who wrote a novel, long before One Hundred Years of Solitude, called Pedro Páramo. But García Márquez certainly utilized magic realism as it has never since and had never before been utilized. And that became another influence on my work. I was mostly involved with doing realistic films. But by the time I came around to Sorcerer, I saw the opportunity to do realistic stories, but with a kind of magic overtones. Just a little hint, as there is in all of our lives. There is a hint of the supernatural and of magic. If we didn't have magic in our lives it would be tough to live past Ezekiel Emanuel's sell-by date. Magic and faith, or a belief in something, I think, play a very important part in all of our lives. And in the way I came to this title, which is very– It's not an obvious title for this picture. But I started to think about fate, and how fate controls all of our lives. None of us had anything to say about how we came here, and we're going to have very little to say about how we leave. And in the case of this film, the evil wizard of Sorcerer is fate. Fate is controlling the destinies of these four men. They're not controlling their own destinies. The other thing, you know, and there's a lot to be said about the idea that no matter how hard we try or how long and hard we work, it all ends the same way. You know. And, you know, that's an idea that has consumed me for some time. And the only film I ever made that expressed my deeper feelings about that stuff is Sorcerer.

Haden Guest 36:33

Let's take some questions from the audience. I'm sure there are some. So if you just wait, there are microphones on either side. So we could start with the gentleman who's standing. There's a microphone to your other side.

Audience 36:47

Thanks. Thank you for making this magnificent piece of work.

William Friedkin 36:50

Thanks for being here.

Audience 36:51

I remember seeing the ads in ‘77 and planning to go to it. And this is the first time I've seen it.

William Friedkin 36:57

That's great. Well, I appreciate it.

Audience 37:00

I wanted to ask... it's interesting that you mentioned sound, because my question occurred to me when we were watching them getting ready to clear the tree in the woods. The tree across the road. And, the sound is meticulous. And even things that are out of frame, you can hear what's going on, and they're part of the narrative. I wonder, you know, obviously there's a lot of location shooting here. How do you go about creating this radio sound–

William Friedkin 37:36

Soundscape.

Audience 37:37

Soundscape, right. And making the two jive? First of all, who's the genius sound engineer who did this? And I wonder what your reflections are on that?

William Friedkin 37:49

Well, of course, there are many moving parts in the production of every film. It's the most collaborative of media, I would say. You know, if you're a writer, you're alone in front of a blank piece of paper or computer screen. If you're an artist, you're alone in front of an easel with your vision and a paintbrush. But with film, you need what we would call a twenty ton pencil. There are a lot of people that contribute. But I hear all of this stuff. You know, it's true that there are many collaborators and all of my films, but what goes into them comes from my own vision and what I hear. And I then set out to make a soundscape with the same attention to detail as I did to the picture. But I work through a lot of other tremendous people, all of whom make a contribution. And I'm open to everybody on the film. Suggestions. And like, when we made the soundtrack for this DCP we had to remaster it. And the sound engineer, a young man named Aaron Levy, who only gets credit at the end, he remixed the picture. Because if you heard the film originally on an optical track, which is all they had then, it wouldn't have sounded as good, or as rich, or as detailed, because optical track tended to have a hiss. You know, you're hearing whatever sound is going on and accompanying it is “sssssssss.” But magnetic track and the new digital tracks are free of all interference, or everything you don't want to hear. So we had to reconceive the soundtrack for digital to bring out certain things that were engulfed by the optical sound. The explosions, for example. Those were all real explosions, but they were not enhanced. But the optical track would cut them down. With optical track, you know, if you've ever seen a sound curve, you know, they look like polls, or you know, polls that are taken for Democrats and Republicans, whatever.

If you look at the... on a piece of paper, at the significance of each sound, you'll see that the loudest sounds on optical track would go up only to a certain point, a ceiling, and then they’d crash. You know? [WILLIAM FRIEDKIN HITS THE MICROPHONE FOR EFFECT] That's it. You could not get explosions to sound like that originally. But we used the original recordings, the original material, where now you can exceed those optical boundaries. So I had to reconceive the soundtrack with that in mind. A lot of the original prints, the sound was not as remarkable as you can do today. It's one of the reasons why I prefer digital. There are many, and you may want to get into that. There are many schools of thought about that, but I'll tell you, I don't miss 35 millimeter at all. It was a step on the way. It was a long step on the way. It was around for many, many years, as was optical track, for many, many years. You know, the first sound, I think, was on recordings. The first sound for films was on recordings that would play in sync with the picture. And then it went through various other media. What we have right now, is as close to being able to capture the picture and the sound that was intended. And as I said, 35 was never able– It was always a compromise. There were great 35 millimeter prints made. Especially the MGM musicals, which still hold up on old 35 millimeter. They were made with a three-strip Technicolor. Yellow, cyan and magenta. Those three strips of film were used to produce a single color print. And you look at the MGM films in 35, they still look just as good. But not many others do. And that's because of the shortcomings of the media itself. And now we have this, which is a fulfillment of what a filmmaker sees and hears in his or her mind’s eye.

Haden Guest 43:18

We can take one right here. Just wait for the microphone.

Audience 43:25

Mr. Friedkin, you made a film in 1980 called Cruising, which I feel is an incredibly underrated film. Partially because of the emotional reaction that happens during the viewing of the film. It’s something, I think, occurs for all of your films. This is sort of a secondary abstract narrative that comes out of the process that– How much of that you feel, or do you give into, that may not be in your control, it may come through the editing process? As sort of an organic process that may–

William Friedkin 43:52

The editing process is totally under my control.

[LAUGHTER]

That's where a film is made or broken.

Audience 44:00

I mean, sort of, something else that may come out that may not be something you planned...

William Friedkin 44:03

You mean an audience reaction.

Audience 44:05

Yessir.

William Friedkin 44:06

I have no idea how the audience is gonna react to any film that I've ever made. I don't have a clue. It's out of my control. If I was making sequels to the films that are made today, like you know, the spandex movies and stuff.

[LAUGHTER]

Guys flying around in a cape and a mask, solving the problems of the world. I would pretty much know that that was going to be a hit. Because that's what they're watching today. That's it. You know, a Hollywood studio will spend two or $300 million on a digitally produced film, for the most part, and financially, most of them work. But when we used to make films in the 70s, we didn't know what was gonna work. And we especially didn't know and the heads of the studios didn't know. They just decided to make whatever was their own taste. They didn't take polls. They didn't do test screenings. There were a handful of test screenings back in the 30s. But they were largely to tell the filmmakers where the jokes were working and where it was too long or whatever. There's a famous test screening that was made for the film Ninotchka. Have any of you ever seen that? Directed by Ernst Lubitsch and written by Billy Wilder. Starring Greta Garbo. And there's a famous story that Billy Wilder told me about after the test screening of Ninotchka in Pasadena. And he said that he and Lubitsch would normally drive home from a preview in a limousine, and Lubitsch would look at the cards, like this. He flipped through the cards like this, and not change his expression. And then he came to one card, [for] Ninotchka, and he stopped and started to roar. And Billy said, “What is it?” and Lubitsch handed it to him. And for the rest of his life, Billy Wilder had this preview card framed on his wall with his Picassos and Brocks and Giacomettis. And he had this card framed and the card read: “This is the funniest movie I ever seen. This movie is so funny, I peed in my girlfriend's hand.”

[LAUGHTER]

So... I don't make this stuff up. So what can I tell you? I mean, that to me states right there the value of a preview.

[LAUGHTER]

You make the film you want to make. If you're concerned that the jokes don't play, you know, run it for a group like this and see if you laugh. If you don't laugh, the jokes aren't working. But if I had gone through the preview process on The Exorcist, I would still be cutting the film. There's no way. Where it says, you know, “What didn't you like about the film?”

[LAUGHTER]

No one's not gonna say, “A 12 year old girl masturbating with a crucifix.” You know, nobody likes that. Not even me.

[LAUGHTER AND APPLAUSE]

Me least of all, but that's the story! So, no, I never previewed The French Connection. The studio didn't understand The French Connection. They wanted me to put narration in it. They didn't get it. The guy who was running the studio then. He was not the guy who greenlit it or who made it. It was a different guy. And he didn't get it. And he wanted me to put narration in, which would have killed the picture. Certainly made it stupid, you know. But, so I don't preview a film. Because of the card I saw on Billy Wilder's wall.

[LAUGHTER]

I don't think my constitution is strong enough to stand that reaction.

Haden Guest 48:52

Let's take a question from the woman in the back, right there.

Audience 49:00

I've never seen this film before. And I'm absolutely blown away by it. But, in particular, I have a question about—no pun intended, absolutely—the scene where the charred remains are returning to the loved ones in the village. And it's so dense and so tight, incredibly claustrophobic. And then the mob violence that ensues, due to their grief. You mentioned that you made documentaries and I didn't know that. And I was curious if you have the same kind of pride in your documentaries, or whether they were done from self assigned assignments or whether they were done, you know, on assignment or for commercial purposes.

William Friedkin 49:39

That's very astute. Before I read García Márquez, my approach to filmmaking was documentary. Which is where I started. My first documentary was just rereleased. It was a 16 millimeter film that I made in 1960. It was called The People vs. Paul Crump. And I made the film to save a man's life. I grew up in Chicago, and I went to work at a television station in Chicago right out of high school. And I hated parties. I did then and I do now. I don't go to parties, cocktail parties, or anything like them. They're totally superficial to me. But I went to one that was given by a very prominent socialite in Chicago, who produced some of the television shows that I directed for PBS in Chicago. And every Friday night, she would give what you'd have to call a soiree. She had a wide group of friends and these parties are written about in one of the Malcolm Gladwell books. I'm not sure which one. But this story that I'm telling you is in this Malcolm Gladwell book. Because she brought people together. I mean, at one of her parties there would be justices of the Illinois Supreme Court, the chairman of Northwestern University, the Dean of the English department, Lenny Bruce, the comedian. She’d bring together a wide variety of people, and she always used to invite me to one of our parties. I was in my early 20s. And finally, I went. And there was a room of, at least, double this many people in her mansion on the Gold Coast in Rush Street. Off Rush Street in Chicago. And I remember standing up against a wall, you know, trying to pretend that I wasn't there. And I had a drink, and standing this close to me was a priest who had a martini.

[LAUGHTER]

And he had a collar as well. And I didn't know what to say to him, as I've never known what to say to anyone at a cocktail party, that's of any significance whatsoever. But I said to this priest, “Father, where's your church?” And he said, “Oh I don't have a church or a parish,” he said, “I'm the Protestant chaplain at the Cook County Jail, on death row.” And that got my attention. And I said, “Have you ever met anyone on death row that you thought was innocent?” And he said, “Yes, there's a guy, right now, who's going to the chair in six months. And both the warden and I think he may be innocent.” That the Chicago police had beaten a confession out of him. He was an African-American. And he had been on death row for seven years. This was on a Friday night. On Monday I called the man. His name was Father Robert Serfling. I called him at the county jail, and I asked him if I could meet this fellow, Paul Crump. And he said, “Well, why would you want to meet him?” I said, “I don't know. I work in television. Maybe I could do something to help him.” He said, “Nobody can help him. He's going in the electric chair. His last writ of certiorari was denied by the United States Supreme Court. He's done. He's had his appeals. The only thing left for him is a pardon by the governor, and that's not going to be forthcoming.” But anyway, he and the warden allowed me to go down to death row at the county jail and meet the gentlemen Paul Crump. C-R-U-M-P. And I met him, I listened to his story. I had no idea how to make a film. I was only doing live television, which has nothing to do, stylistically, with the making of a film. The only thing I took from my work in live television was, you had to learn how to collaborate. You had to be able to communicate with the technicians and the crew and the actors, so you could communicate with an audience. But that's all. The techniques are totally different. Anyway, I went down with two other people, who had never made a film. The warden allowed us to come on death row and film the documentary about this man's rehabilitation. And in the film, I recreated the circumstances of the crime. I introduced a lot of the witnesses and the lawyers, and heard their stories. And I reached a conclusion then, and that's what the film says, is that this guy was beaten within an inch of his life and confessed. And I made the film to save his life. And the first person it was shown to was Warden Jack Johnson, of the Cook County Jail, who had already executed three men in the chair, and didn't want to execute a fourth. And so he allowed me to make this film. The cameraman on the film was a guy named Bill Butler, who later, I brought out to Hollywood, and he later photographed Jaws, and One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest and a lot of stuff. But he and I learned how to make a film by making this documentary to save this guy's life. And it was first shown to the governor, who, a couple of days later, sent me a note, which I still have, in which he said, “Congratulations on your film. I want you to know that my parole and pardon board has voted, two to one, to let Mr. Crump go to the electric chair. But I was so moved by your film that I'm going to pardon him to life imprisonment without possibility of parole,” which he did. And then... but it saved a man's life. And after about 30 more years, Crump was cut loose and went back to the custody of his sister, in South Chicago, where he had a rough time of it, because he had been imprisoned, by then, for about 40 years. But I thought, this was my first film. It's been rereleased by Facets, out of Chicago. It was shot in 16 and it’s now a Blu-ray. But I thought, “My God, film is so powerful. You can save someone's life with film.” And then I went to Hollywood.

[LAUGHTER]

And I was completely cleansed of that belief.

[LAUGHTER AND APPLAUSE]

Although there have been one or two other films, I think, one definitely by Errol Morris–

Haden Guest 57:33

Which was clearly inspired, I think, by The People vs. Paul Crump.

William Friedkin 57:37

Yeah. And who also made a film that saved a prisoner’s life.

Haden Guest 57:46

Yes. Let's take a question here. The gentlemen in the plaid shirt. Yes, that's him with–

William Friedkin 57:52

Red hair. Yeah.

Audience 57:58

Thank you. So, me and my friends are in film school. We're aspiring filmmakers.

William Friedkin 58:06

You’re perspiring filmmakers, you said?

[LAUGHTER]

Audience 58:09

Yeah. We perspire and aspire. But I was just curious if you had, like, maybe five quintessential films for young filmmakers.

William Friedkin 58:19

I don't know. I do have five quintessential films. But I'm never sure, whether somebody else will have the same reaction to these films as I do. I'm never sure. I know that Citizen Kane is a quarry for filmmakers. It's all there. The very best kind of cinematography, editing, acting, screenwriting. A film that keeps its mystery to the very end. The lighting, the art direction, the use of opticals in 1940, where they were virtually handmade. As opposed to the digital world today. But my five quintessential films aren't going to mean a damn thing to you and your friends, who have grown up with the new zeitgeist, you know, with which I have absolutely nothing in common. Some of the films that I'm sure you guys like, I don't get them at all. And it's not your fault or their fault. There's just a different zeitgeist. The films that have influenced and inspired me were Citizen Kane, The Treasure of Sierra Madre, All About Eve, which is a great screenplay and a great film. A film called Blow Up by Antonioni, which is a fabulous film. A film called Belle de Jour by Luis Buñuel. You know, these to me– and the MGM musicals! That stuff is just great! It's tight. You’ve got this beautiful music. And that stuff cannot be made today, because those musical films were utilizing the popular music of the day, which was not rap or hip hop. It was Cole Porter, and George Gershwin, and Rodgers and Hammerstein, and Rodgers and Hart. That stuff was the popular music of the day. And people could dance to it, and fall in love to it, you know, and be entertained. There's no greater film experience that I've ever had than, seeing over and over again, An American in Paris, Singing in the Rain, Gigi, and The Band Wagon. Those are way up at the top. But for one film that just is like—I mean, if I was living in France and wanted to be a writer, I would continuously read and reread À la recherche du temps perdu by Marcel Proust, which I do continuously read and reread. If I was an American, a young person like yourself, who wanted to be a novelist, I would read The Great Gatsby, which doesn't take a lot of your time. And Proust does. I mean, Anatole France said that, “Life is short, but Proust is long.”

[LAUGHTER]

But Gatbsy is a short book that’s just a killer. And then there's also a short story by Ernest Hemingway, which I advise you to read, called The Killers. The Killers, by Ernest Hemingway, has influenced so much. It influenced the playwriting of Harold Pinter, who based his play, that I filmed early in my career called The Birthday Party, on Hemingway's short story The Killers. But if I was a young, aspiring, perspiring filmmaker, forget all the spandex stuff. That's all done by guys on a computer. If I were going into film today, I would not try to be a director. I would go into film as a computer engineer. You know, making films on a computer, because they are made on a computer today. All of the effects and all the backgrounds. And, you know, we're almost at a point where all the actors will be computerized and they'll be avatars for real actors.

But I would see Citizen Kane, because it's like a quarry for filmmakers. You know, hands-on filmmaking. Not the digital stuff, which is an art form in and of itself. And it's probably a great part of your education, digital cinema, yes? Using Bolexes. Wrong again.

[LAUGHTER]

But that only speaks to the fact that– Where are you studying? Here? At Emerson.

[LIGHT APPLAUSE AND LAUGHTER]

Thanks, Dad.

[LAUGHTER]

That only speaks to the fact that Emerson can’t afford computers!

[LAUGHTER AND APPLAUSE]

Because all these other guys, at UCLA, and USC and the AFI, you know, around where I live, they're all on computers making stuff. And that is not simply the present, it's the future. And I never used a computer on a film. Everything that I did, all the effects in my films, we had to do them mechanically. It doesn't make them better. They would, in fact, probably look better on a computer today. The Exorcist, if I were filming it today, I would do it using CGI. Computer generated imagery. But it didn't exist when I was making that film. We had to create all that stuff mechanically. I don't know how much interest that will be to your generation. And I gotta tell you, I just don't relate to a lot of the most popular films of the day. I don't relate to it. So I'm not a good adviser for that. But you want to see how a screenplay is constructed? See All About Eve. You want to see how a movie can be great? That’s Citizen Kane. An adventure story that you completely believe from beginning to end is happening to these people is the Treasure of the Sierra Madre. These are my classics. But I don't know how they relate to your generation. I really don't. You might not get the same thing that I got out of them.

Haden Guest 1:05:39

This gentleman in the front has been very patient, yeah.

Audience 1:05:43

I've read that Costa-Gavras and the film's he has been a very big–

William Friedkin 1:05:47

I'm sorry, what did you say?

Audience 1:05:48

I've read that Costa-Gavras and the films [have] been a very big inspiration to you. And in Sorcerer, at the beginning, when the French businessman is told by the prosecutor that he has 24 hours left. To me, the mise en scène, and also the way that the actors presented themselves, seems very similar to the scene at the end of Z, when the young prosecutor tells all the generals that they're going to get in trouble. Is there any substance to this comparison?

William Friedkin 1:06:15

Who are you talking about?

Haden Guest 1:06:16

Costa-Gavras. Z.

William Friedkin 1:06:17

Costa-Gavras! Oh, yes! That was a great influence on me, that film. I had made documentary films, but I never knew that you could actually do a whole feature film in documentary fashion, until I saw the film Z by Costa-Gavras. And yes, that was a great influence on me. Not specifically scenes like the ones you mentioned, or dialogue. But simply the approach to the story was like documentary filmmaking. That had a great effect on me. And he's now the president of the French Cinematheque. And a good friend. And I greatly admire the early films of Costa-Gavras. Yes, absolutely.

Haden Guest 1:07:10

Let’s take a question on the edge over there. Yeah.

Audience 1:07:15

Hi.

William Friedkin 1:07:16

Hello, sir.

Audience 1:07:17

My two films, actually, that I love of yours I encountered, actually, as a younger kid, believe it or not. And it was Boys In the Band and it was Cruising. Actually, I saw them on this thing called Starcase, which back then– I don't know if you know what Starcase was?

William Friedkkin 1:07:31

No, I don't.

Audience 1:07:32

It's kind of like, before even cable or even VCRs, it was the only way to watch first run movies. And the funny thing was, it was a Friday night—never forget—my best friend and me were going to see a horror movie again. My parents were like, “Seeing too many horror movies. No, you go home, you watch Starcase.” Well, the movie we watched was Cruising.

[LAUGHTER]

Audience 1:07:54

Which was kind of interesting. I don't think they knew what that was.

William Friedkin 1:07:58

That's a credit to your parents' judgment.

[LAUGHTER]

Audience 1:08:02

I agree!

William Friedkin 1:08:03

As are you, sir!

Audience 1:08:05

Yes! Fooled them. But a question I have for you, and I might have just been hallucinating at the time, but as a young kid seeing that film, I recall to this day, the very end of that film, where Karen Allen is trying on the jacket–

William Friedkin 1:08:21

Yes.

Audience 1:08:21

–the glasses, the cap, goes into the bathroom. I recall there was a scene where the mirror was open a little bit and you actually see her in the mirror, which almost... you could almost see that it looked exactly how the killer worked throughout the film.

William Friedkin 1:08:40

That's true.

Audience 1:08:42

Now, when you say–

William Friedkin 1:08:43

That's not the last shot.

Audience 1:08:44

That's... okay. But–

William Friedkin 1:08:46

The last shot is Pacino. It's Pacino in the washroom, shaving and he looks into the mirror and then he looks right into the eyes of the audience. Because the film is about identity and mistaken identity. And the film, in a very unsubtle way, asks people who watch it to look within themselves, you know, before passing judgment. That was one of my intentions in making that film. But you're right about the image of Karen Allen, just before that, in a mirror in the living room.

Audience 1:09:30

It's great, because it's ambiguous. You don't really know, actually, who is the killer in that film.

William Friedkin 1:09:35

Well, that film was based on an actual set of murders. Would you like to hear a little bit about how I made that film? Where that came from?

[APPLAUSE]

There's a guy in The Exorcist. How many of you have seen The Exorcist? Okay, if you haven't seen The Exorcist get the hell out of here.

[LAUGHTER AND APPLAUSE]

There's a guy in The Exorcist... There's a scene that we shot at the Bellevue Hospital in New York. And it's an arteriogram. It's where they are trying to examine the little girl's brain, this neurosurgeon. And he is inserting a needle into her carotid artery, and squirting a fluid—this was an actual technique, the arteriogram—that goes up into the brain and outlines the arteries of the brain, to see if any of the arteries are broken, and to see if that was the cause of her misbehavior. Now, everyone who saw the film knew it was about demonic possession, except this neurosurgeon. But anyway, I shot it at the NYU Medical Center with an actual neurosurgeon and with his assistant. And they're both in the film. His assistant is the young man who helps Linda Blair onto the table and prepares her for the arteriogram. And he makes her comfortable, and puts a pillow under her head, and makes sure she's covered with a sheet. And that young man, his name is Paul Bateson. And he was the actual assistant to the neurosurgeon at NYU Medical Center. And he was the first person that I had ever seen in the workplace who was wearing an earring and a metal stud bracelet, which just wasn't done, at that time. And especially in a hospital environment. And I just made a kind of a mental note about that and forgot it. About five years later, I saw his picture, an enormous close-up of him on the front page of The New York Daily News, where he had been accused of five, what they called, “CUPPI Murders.” CUPPI—C-U-P-P-I—was police slang for “Circumstances Unknown Pending a Police Investigation.” And these were body parts found in plastic bags in the East River, floating around in the East River. And Paul Bateson, I'm thinking where have I seen...? I know this guy! Where have I...? This is the guy who was working at NYU Medical Center! And I saw his lawyer's name in the article. These men— all men—had been cut up into body parts and tossed in plastic bags. And there were many other such murders, but he was charged with five of them. I saw his lawyer's name and I called his lawyer and asked if I could go to see Paul at Rikers Island, where he was awaiting trial. And word came back that he would see me. And I went to see him, under massive guard, but in a private room. And when I came in, the first thing he said to me was, “How's the film doing?” This guy's up for five murders. And The Exorcist had still been playing, and he was in it, so he asked me, “How's the film doing?” And I said to him, “Paul, did you kill these people?” And he said, “You know, I only remember killing the first guy. I don't remember the others,” he said, “I was so high or stoned. I just don't remember that.” And the first guy he meant was a man called Addison Verrill, who was the theater critic for Variety. And Paul used to go to a club called The Mineshaft, which was a S&M club in Lower Manhattan. He would pick up guys, take them home, they would get stoned, and he would hit them over the head and then cut them up. And what, I guess, he had failed to notice was in very small print, almost illegible print, at the bottom of all these bags, it said “Property of NYU Medical Center, Neuropsychiatric Division.” And so the police traced these bags right to him.

I got his whole M.O. And then, I happen to know the guy who owned all of these clubs. He was the head of the Gambino family in New York, and he was a friend of mine. His name was “Matty The Horse” Ianniello. And he had done many stints for armed robbery, but I knew Matty, he was like a fan of The French Connection.

[LAUGHTER]

And Matty was getting either paid tribute or outright owned almost everything on the West Side of New York, from top to bottom. They had to pay the Gambino family and Matty was the guy then, and I asked him if I could shoot in one of his clubs, The Mineshaft. And he put me in touch with the manager, and I went down and met him, and I went into the clubs, and shot the film in all of the actual clubs where the murders had taken place, and which were still operating. And this was in 1979. We started shooting in ‘78 when the deaths started to occur and pile up, and they didn't have a name. And a year or so later, it was called AIDS. But there were all these mysterious deaths. And especially in those clubs, the S&M clubs. All the people that were involved with Cruising, even some of the guys on my crew, are long dead. And so it was this Paul Bateson, his story, that I filmed. And what they got him to do was to confess to another eight of the unsolved murders, for which they lowered his sentence. They reduced his sentence. He did 35 years in prison, after being charged with 12 or so murders. And he's out today. He got out a couple of years ago. Now, I don't know where he is. More importantly, he doesn't know where I am.

[LAUGHTER]

I'm here at the Harvard Film Archive.

[LAUGHTER]

You're not there, are you Paul? You’re not out there, are you? But I'm sure that he lives under an assumed name and is in the Witness Protection Program. I don't know that he's out among the population. But that's how Cruising came about. And that the murders were never really solved. And so in the film, as you point out, they're not solved. There are a lot of clues, but no solution. And this is true of so many murders that take place. In this country and everywhere. Haden?

Haden Guest 1:18:10

Maybe we’ll take maybe one more question? All right, let's take–

Audience 1:18:15

[INAUDIBLE]

Haden Guest 1:18:22

Question about To Live and Die in L.A. and if Mr. Friedkin could speak about the film, and the question whether it came out as he wanted it to.

William Friedkin 1:18:30

Pretty damn close. I had met a man who had recently retired from the U.S. Secret Service. His name is Jerry Petievich. And he was a Secret Serviceman for about 19 years and then he retired. And the life of a Secret serviceman seemed to me to be totally surreal. One day he’s protecting the President of the United States or a foreign dignitary. And the next day, he's out chasing a guy in a very bad neighborhood for a $50 bum credit card, you know. And from protecting the President, and sitting in a room with the President, playing poker with the President and other Secret Service agents, to chasing some guy for a bad credit card seemed to me to be a wild ass kind of a job. And Jerry introduced me to a number of other agents. And he wrote a book about his experiences called To Live and Die in LA. And most of the characters are based on people that he worked with, who I later met. And the film opens, as you know, with one of the agents bungee jumping off the Vincent Thomas Bridge. There was a guy that used to do that. These guys were so in need of the relief of tension, you can't believe it. And they would go a little crazy. And I saw the job as being very weird. Very strange. And all these guys had interesting peccadilloes, you know. They were all a little bit off the wall. They were not the previous image that I had seen in films or television, about the majesty of the US Secret Service. These guys were wacko, because you can imagine, you know, you put on your suit, and you put on a badge, and you put on a gun belt! You go out there to protect somebody and you can get killed! You can be the guy who takes the shot! And, you know, I don't know how many of us would be willing to do something like that. But that is the job. And I found that these guys were terribly stressed out, but could not show it. And so I made To Live and Die in LA with that in mind. And the caper was based on an actual case that had occurred during Petievich’s time in the Secret Service. When two agents, who needed to make a buy of counterfeit money— using real money—busted a guy who was selling stolen gems and carrying the real cash—$50,000 in cash—in a money belt. So I took that story and I added a chase, because at that time, I had a lot of ideas for chase scenes. And the one in To Live and Die in L.A., I think, for me, is as good as the one in The French Connection. But I would never have ever filmed a chase scene— I wouldn't have gone near it, if I had seen the Buster Keaton films before I made The French Connection. I had never seen a Buster Keaton film. And years later, I saw about seven of them that have the most phenomenal chase scenes I've ever seen. That make mine look like, really, amateur night. And I don't know how the hell they did it! Everything you see. How many of you have seen a Buster Keaton movie? Aren’t they great? They're unbelievable! Yeah, look at that stuff! That's pure filmmaking. Not even sound, but they're funny, they're droll, they're exciting! And the chase scenes are unimaginable. It's like I could never paint somebody's portrait because I've seen Rembrandt. I've seen so many Rembrandts that I've never picked up a brush! I was lucky, growing up in Chicago, and going to the Art Institute, where they had a few. And then, early in my life, I went to New York to the Metropolitan Museum, and saw rooms filled with Rembrandts. And that says it all about portrait painting. But I have never felt, with the possible exception of Citizen Kane, that there were any films that intimidated me, the way like a Rembrandt portrait or a Beethoven symphony. And today, even a Mahler, or a Shostakovich symphony. I love them so much, but they're intimidating. They're daunting. I don't know how somebody writing classical music can go near the notepaper, if you listen to a Beethoven symphony. What are you going to do? And it's for the same reason that modern art has become so decadent and stupid, frankly. People are lined up in New York, in front of the Whitney, to watch a Jeff Koons exhibit.

[LAUGHTER]

I mean, a bronze bunny, you know. A bunny! And other stupid stuff! Then there's this guy, Damien Hirst. You know who he is? He's a guy that puts three basketballs in a fish tank.

Haden Guest 1:24:52

Oh, that's Jeff Koons too, yeah.

William Friedkin 1:24:54

What?

Haden Guest 1:24:55

That's Koons. He has the shark, yeah.

William Friedkin 1:24:56

That’s Koons. Yeah, he put three basketballs in a formaldehyde tank, and that was shown at the County Museum. And all of that stuff, to me, I mean, anything is art today. Anything. The Piss Christ, you know? I can’t– That's it. My mind won't let me go any further. But, good lord, you ever seen a Rembrandt? Well, in my case, that became the Buster Keaton films. I kept wondering, after seeing about seven of them, why I ever bothered to film a chase scene. You know? The only thing I added to it, I guess, was an interesting soundtrack. But they don't compare to what Keaton did with much more limited resources, in the silent era. You have anything–

Haden Guest 1:26:01

Well, nothing compares to the films of William Friedkin, who will be back with us tomorrow night with Killer Joe.

[APPLAUSE]

William Friedkin 1:26:08

Thanks for coming. Thank you all very much. Thank you. Thank you very much. Thank you. Thank you very much. I appreciate it. Great to be here. Great. Thanks, Haden.

©Harvard Film Archive

Related film series

Explore more conversations

Bahman Ghobadi

Scott MacDonald, Robb Moss & Stephanie Spray

Kelly Reichardt

Yoojin Moon