The following selection of thirty+ LGBTQ movie posters offers a vibrant snapshot overview of the evolution of LGBTQ movie marketing history. These are just a few of my favorite items from my 2005 soft-cover coffee table tome, The Queer Movie Poster Book.

When I was commissioned by Chronicle Books to create that volume, I hired a museum photographer to shoot large-format rostrum shot transparencies of the full-size posters in my collection; those transparencies and their corresponding digital files are now all part of the Jenni Olson Queer Film Collection, along with a significant number of the actual posters.

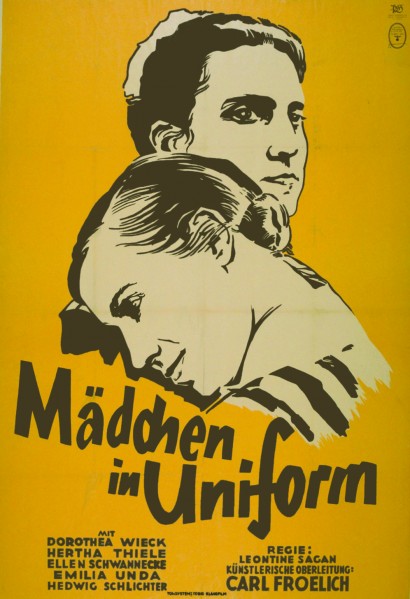

This sampling included here covers seventy years—starting with a movie theater pamphlet from the original US release of the 1931 German classic, Maedchen in Uniform (which is considered to be the first lesbian film ever made) up through the 2001 modern American butch/trans classic, By Hook or By Crook, on which I served as a consulting producer.

ORIGINS OF THE COLLECTION

I don’t remember when I acquired my first queer movie poster, but I do remember that at some point I realized that the marketing of LGBTQ films to the mainstream was a uniquely problematic art form.

As the film critic for one of the local gay newspapers in Minneapolis, Minnesota in the late 1980s, I was the happy recipient of invitations to press screenings for all the upcoming LGBTQ indie movie releases. I got to see and write about films like I’ve Heard the Mermaids Singing, Waiting for the Moon and Longtime Companion.

One of the best parts of attending these screenings was being given the press kit materials on arriving at the theater, to be able to do a quick bit of deeper research before the film started and then to take home and use as a resource for writing the review. Yes, this was before the Internet Movie Database existed so in order to be able to cite the names of the actors, writer, director, etc. you had to have it on hand (more than once I even had to call the publicist asking them to track down info I needed).

Generally the press kit included all basic credits, synopsis, often a director’s statement and sometimes even an interview with the director. It would also include a set of 8” x 10” production stills to bring back to the office so we could run an image with the review. And sometimes the kit would also include an image of the poster art.

I had started collecting vintage LGBTQ movie trailers around this time, and I also began searching out and acquiring the posters for those same films. The oldest trailers I could find in 35mm film format really only went back to the 1960s, but with posters it was possible to unearth even older items—including many of the images in this slideshow.

POSTERS IN THE EXHIBIT

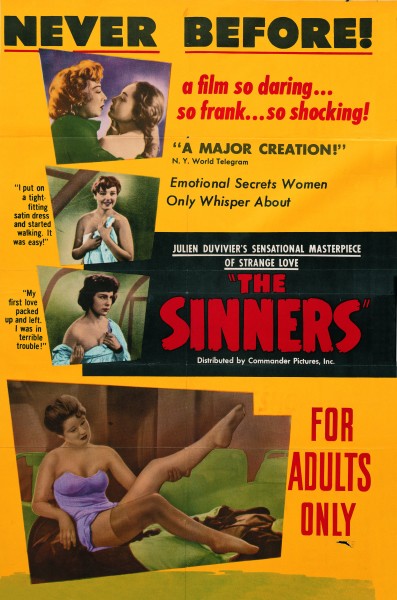

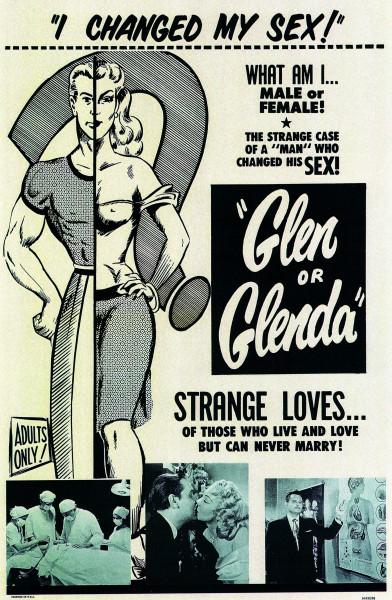

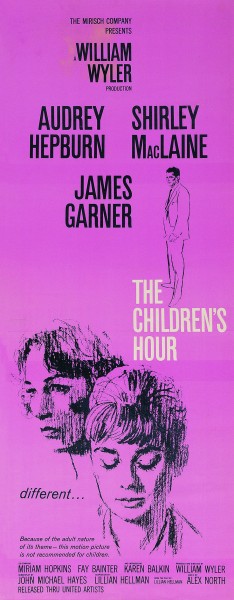

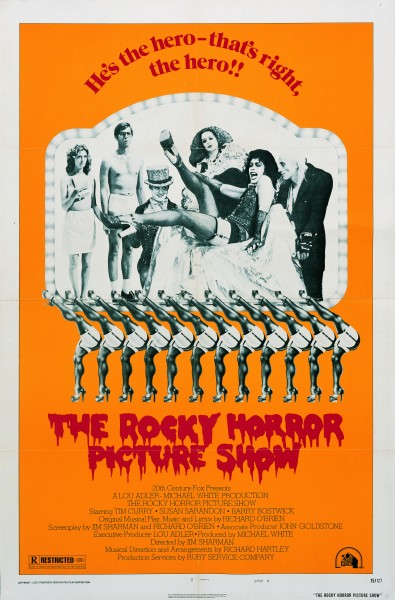

The first batch of posters you’ll see here gives a glimpse of the olden days and an impression of how backwards and sensational (tho also often graphically interesting) those marketing campaigns could be. The poster for The Christine Jorgenson Story (1970) is emblematic of that tone of sensationalism with which Hollywood historically approached LGBTQ lives and stories—it’s pretty much the worst of the worst.

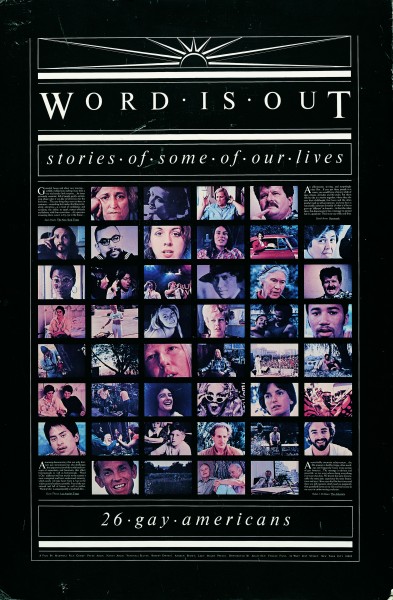

The next handful of titles reflects the wonderful naive earnestness of the independent gay films of the 1970s, starting with Wakefield Pool’s gay adult classic, Boys in the Sand (it’s title is a riff on the 1970 classic The Boys in the Band which also has a great poster, but we only have so much room here so you might just have to go get a copy of my book!).

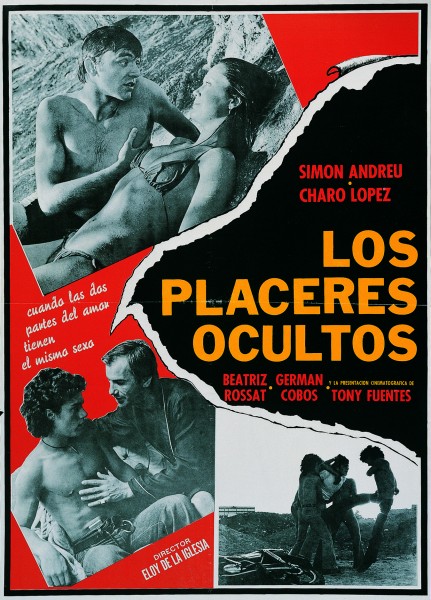

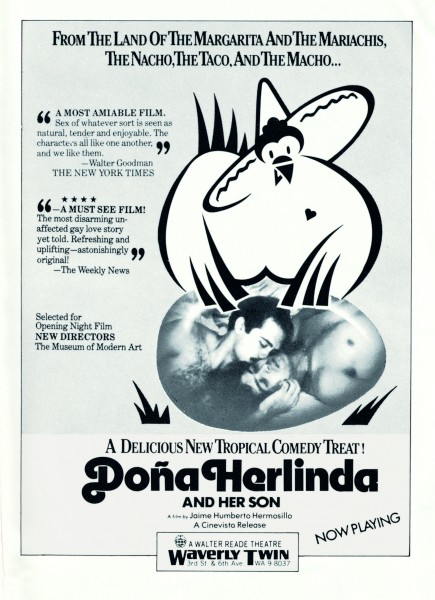

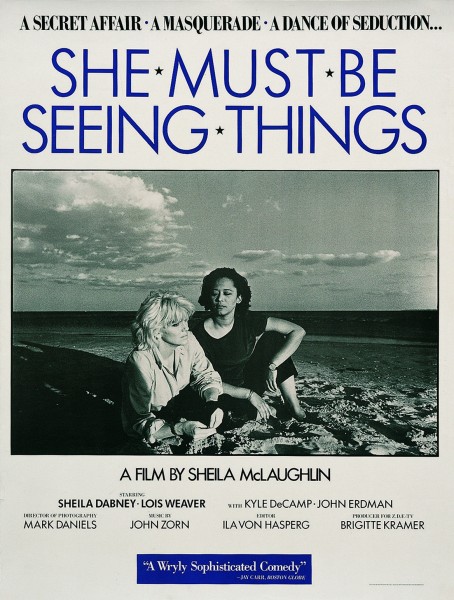

While certainly depictions of LGBTQ characters and stories in the indie films of the late 1980s were generally a vast improvement from earlier representations, you also can’t help noticing that the marketing materials for these films still reflect a certain reticence or slightly retrograde or watered-down quality. The taglines and poster art designs often seem desperate to convince straight audiences that they should not be put off by the gay themes. Of course it makes sense that the companies releasing the films wanted as wide an audience as possible to purchase tickets. Basically it seems like they want to have it both ways.

The poster art for Desert Hearts is a quintessential example. The original US poster included here conveys the lesbian theme of Donna Deitch’s now legendary 1985 queer period love story, as we see wild and sexy Cay (Patricia Charbonneau) making eyes at prim and proper Vivian (Helen Shaver). In an obvious effort to appeal to a broader audience, who presumably would not come out to see a mere lesbian romance, the lovers are flanked by a pair of minor characters, a man and a woman, both of whom are barely seen in the film.

Equivalent to this, gay director Norman Rene’s beautiful 1991 AIDS drama, Longtime Companion went with the ultimate universal de-gaying tagline: “A motion picture for everyone.” When I wrote my review—not really knowing anything at the time about who Norman Rene was—I noted the equally problematic phrasing of his quote in the press kit: "It was essential that the people we encounter are human and identifiable, so that the film is not about New Yorkers and gays, but about people with whom audiences could identify." (New Yorkers and gay people are not human and identifiable?, I snarked.) The film’s marketing designers also attempted to de-gay the home video release poster by incorporating the minor character female friend. Thankfully, the theatrical poster (included here) offers a warm and loving image of two of the male leads affectionately embracing.

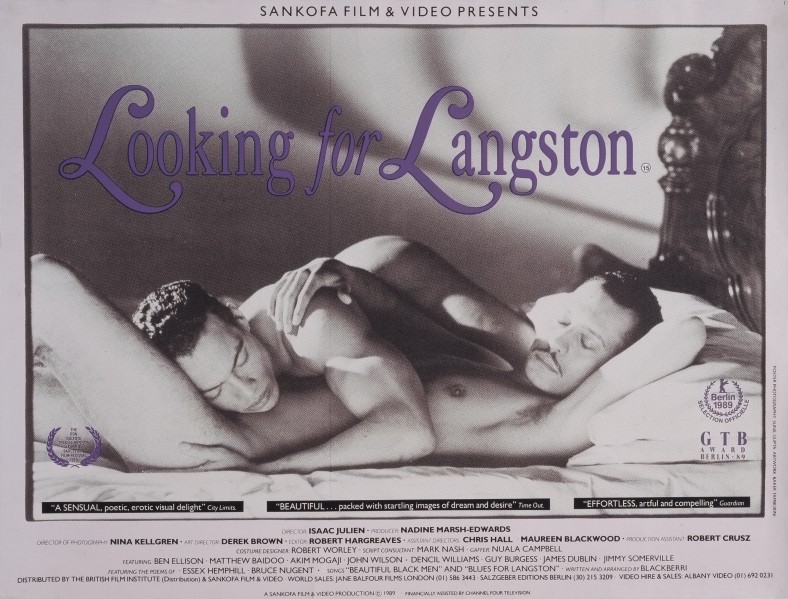

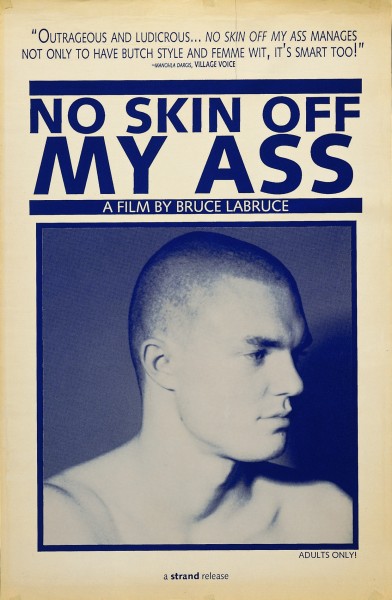

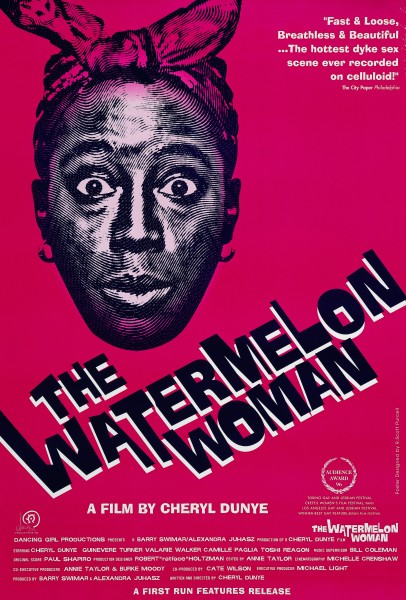

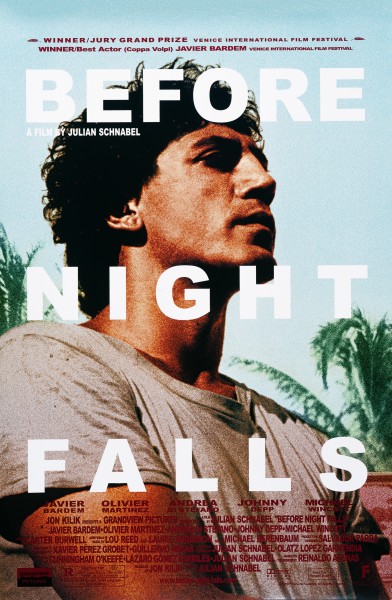

Fortunately, as you’ll see flipping through the rest of the images here, these often diffident marketing campaigns gave way to the boldness of the New Queer Cinema films with promotional approaches that generally were not afraid to be as queer as the films themselves.

Without further ado, please enjoy! – Jenni Olson