Caught in the Net.

The Early Internet in the Paranoid Imagination

On January 13th, 2018, Hawaii received an Emergency Alert via television, radio, cell phone: “BALLISTIC MISSILE THREAT INBOUND TO HAWAII. SEEK IMMEDIATE SHELTER. THIS IS NOT A DRILL.” My friend was jolted awake by the notification; another friend, running a full café in Hawaii with tourists waiting for tables lining the walls, reported that crying employees immediately left to meet their families at home. Half of the customers also ran out the door, leaving their food paid for, uneaten. The rest of the tourists, un-pushed by their push notification, stayed put, biting into French toast and Eggs Benedict, sipping locally sourced coffee poured by the owner and her husband.

If this scene feels like a droll mash-up of Dr. Strangelove and Alexander Payne’s The Descendants, it also feels like a scene from WarGames—and felt even more so when it was revealed that the alert was sent by an oft-disturbed employee who mistook a drill for a legitimate disaster. What existed as a private military blunder in the (fictional) film WarGames became, in 2018, an instantaneous viral panic, spreading through cyberspace as fast as a crashing missile.

But let’s be real: Who can’t relate to Hawaii’s disturbed alert-sending employee? Who isn’t ready for incipient disaster, one shocking tweet, one iPhone buzz away? Caught in the Net. The Early Internet in the Paranoid Imagination was initially crafted during the fall of 2016, during a semester violently bisected by an infamous presidential election. Stunned media commentators began to seriously consider—in the wake of Wikileaks email releases, Russian interference and fake news, Twitter trolling and algorithmically predestined social media bubbles—how the Internet, often tied to utopian narratives of “openness” and “connectedness,” may be seriously harming democratic structures.

Needless to say, Internet-derived national insecurity has not dissipated.

In the midst of that 2016 chaos, I wondered: was there an “origin story” for the anxiety and paranoia that felt so unprecedented? It took little research to learn that the Internet has been a long-lodged structure in the paranoid imagination. This series therefore charts both the consistency of Internet-related fears and the ways that these fears have shifted over time, from the Military Industrial Complex to Edward Snowden. The result of this excavation is a series charged with an arresting push-pull dynamic: on the one hand, almost all of the featured films are intoxicatingly entertaining; many of them pulse with the ruthless energy of a street preacher shrieking Revelation. On the other hand, they carry the seeds of the all-too-real hysteria released in the Hawaiian café. Watching these films can feel like revisiting early footage of a developing problem that has only seemed to worsen.

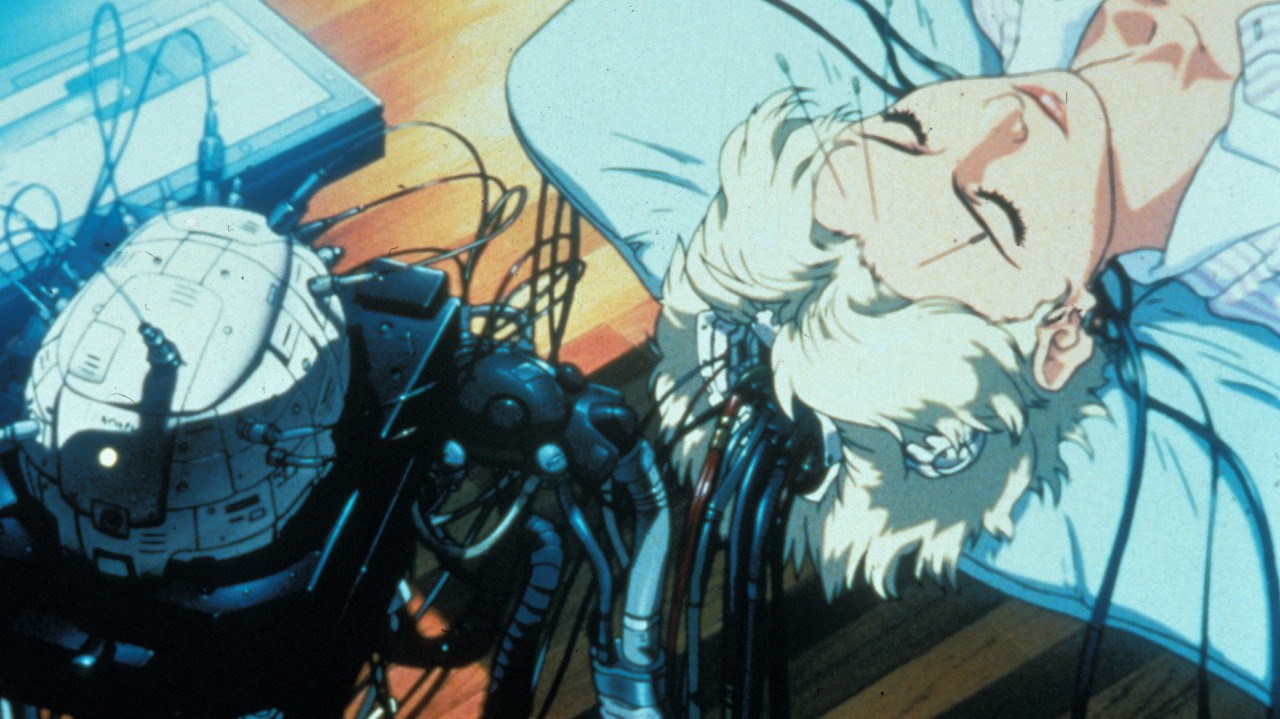

Foucault wrote in The Archaeology of Knowledge: “Beyond any apparent beginning, there is always a secret origin—so secret and fundamental that it can never be quite grasped within itself.” While the origins of our Internet-oriented anxieties may not be simply grasped, these films help us feel around the edges of these fears, locating them in armored police helicopters, green-tinted video games, battles over web addresses, deranged digital abstraction, tortured cybernetic bodies, pleasured cybernetic bodies, present-yet-absent ghosts, and—most significantly—governments and corporations, sources of incalculable power, hell-bent on reducing humanity for petty benefit.

It is a standard cultural studies mindset to see film as a symptom of cultural conditions. Yet through this program, we witness something slightly, yet startlingly, different: Films as symptoms of fears that seem prescient, even prophetic. As we witness our current society living out fears of the past—rendered both more insidious and more banal than our cinematic nightmares—we inevitably wonder how to deny fears of the present, for the sake of the future. The Harvard Film Archive is proud to partner with the Institute of Contemporary Art, currently displaying the significant retrospective Art in the Age of the Internet, 1989 to Today, as well as a variety of local artistic institutions, to tackle these insistent questions together. – Nathan Roberts, Series curator, PhD Student, Film and Visual Studies, Harvard University