The Image Book

(Le livre d'image)

Switzerland/France, 2019, DCP, color, 84 min.

French, English, Arabic, Italian, German with English subtitles.

DCP source: Kino Lorber

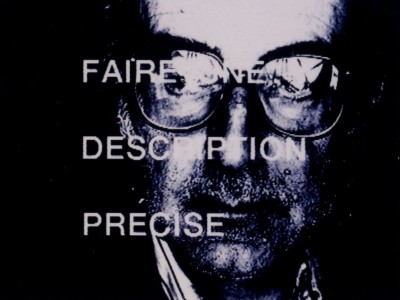

Four years in the making, Jean-Luc Godard’s Le livre d’image could not be more of the moment. It is almost without narrative constraints—the most abstract in the series of collage films that spin off from his epic Histoire(s) du cinema (1988–98)—and is thus as ephemeral as a dream. I saw it twice at Cannes in May, and although I still remember the intensity of the experience, the details have fled my mind.

More rapidly edited and visually explosive than Histoire(s), Le livre d’image revisits 120 years of cinema. A meditative, first-person voiceover comprising literary and philosophical musings, occasionally overlapped by sync-sound fragments and punctuated throughout by music, reflects on a world history that cinema has tried and typically failed to represent. While many of the images are familiar from Godard’s previous collage films, they are transformed here through digital technology—treated with flickers and washes of vivid color, slowed, reframed, made new through the relationship of the eye and the hand that turns the dials on the digital board or that fingers the digital paintbrush and the touch screen. Godard is working toward a film that could be as handmade as a painting, not only for reasons of aesthetic pleasure or for finding, as Stan Brakhage did, a correlative for what the closed eye perceives in darkness, but also to call attention to what the continuity of movement and light in narrative films renders invisible. The visuals do not stand alone as they do in Brakhage, but are always in relation to a text that homes in on the present/absent dynamic of the image and that also, line by line, proves more contradictory than anything Godard ever culled from his familiar favored sources. His own voice dominates a small chorus of speakers, and the mortality evident in its shaky, scratchy tones makes the film nakedly personal. The text is Godard’s by virtue of the way he edits together the words of others and lends them his voice.

In his late work, Godard has moved closer to the 1960s American avant-garde. Le livre d’image is divided into five parts, the last and longest titled “La région centrale,” which is also the name of a 1971 film by Michael Snow that, via a specially built apparatus that can perform separate, sustained 360-degree rotations of the camera, the arm, and the instrument’s base, depicts a primeval area of northern Quebec. Although it would be difficult to think of a film that has less in common with the fragmented Le livre d’image, Godard’s use of Snow’s title reveals something of the near-hysterical, oneiric overload of his own associative method. In Le livre d’image, the phrase la région centrale alludes to the palm of the hand, the place where the fingers (and the film’s five parts) come together; to the Arab world that Western cinema has ignored or suppressed and which Godard fantasizes as “Happy Arabia”; and to Snow’s work in general.

Of all the North American formalist filmmakers, Snow is the most concerned with the tension between image and sound. This disquieting juxtaposition has continually occupied Godard, too, and more than ever in the collage works. Le livre d’image’s multiple audio tracks result in elaborate counterpoints—between image and sound and among audio channels. Perfectly balanced speakers are crucial to the experience, particularly when the sound composition resolves on a single word. Le livre d’image proposes history as a nightmare and the looming end of the world as the phantasm’s conclusion, which we must face with hope. “And even if nothing would be as we had hoped / it would change nothing of our hopes / they would remain a necessary utopia.” Among the film’s introductory images is a black-and-white photograph of a hand with the index finger pointing up—a detail from what is thought to be Leonardo da Vinci’s final painting, St. John the Baptist, ca. 1513–16. In Renaissance art, that configuration of the hand signals a belief in salvation. By the end, all the audio channels synchronize for Godard’s raspingly voiced last words. “Ardent espoir” (ardent hope), he gasps. The voice is ancient; the words demand. – Amy Taubin, adapted from her essay “SYNC OR SWIM” in Art Forum International, October 2018