Inescapable Anxiety

The Films of Paul Sharits

I wish to abandon imitation and illusion and enter Directly into the higher drama of: celluloid, two-dimensional strips; individual rectangular frames; the nature of sprockets and emulsion; projector operations; the three-dimensional light beam; environmental illumination; the two-dimensional reflective screen surface; the retinal screen, optic nerve and individual psycho-physical subjectivities of consciousness.

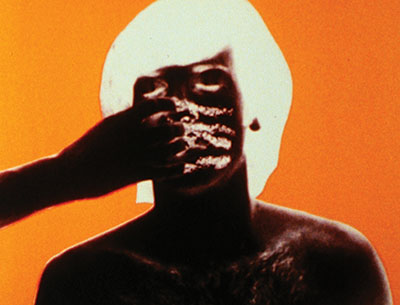

The radical and highly stylized work of American filmmaker Paul Jeffrey Sharits (1943-1993) forever changed the landscape of filmmaking and art, and continues to reverberate within the history of cinema. Driven by what he described as “inescapable anxiety,” Sharits was extremely prolific throughout the 60s and 70s. His films exploded the conventions of both narrative and experimental cinema at the time and were a complete departure from what other “structural” filmmakers, such as Peter Kubelka and Tony Conrad, were making at that time. Perhaps some of the most powerful films ever made, Sharits’ mandala films of the 60s—such as the highly charged Piece Mandala/End War, T,O,U,C,H,I,N,G and Razor Blades—all used the flicker technique to violently alternate between pure color film frames with sexually explicit and sometimes crude still images. Trained as a painter and graphic designer, Sharits “drew” his films first with colored ink on graph paper, as blueprints for the completed films, and then proceeded to meticulously compose them frame-by-frame like musical notes. Stripping the elements of narrative cinema—illusion and imitation—from his work, Sharits instead highlights the materiality of film while focusing on a complete exploration of the film frame. A goal of Sharits’ films was to obliterate the viewer’s perceptions by using flickering light, stark imagery and repetitive sound to deeply penetrate the “retinal screens” and psyches of the audience members, creating a powerful, profoundly visceral and participatory experience.

Paul Sharits grew up in Denver and attended the same high school that filmmakers Larry Jordan and Stan Brakhage did ten years prior. He eventually enrolled at the University of Denver to study painting, drawing and sculpture. Becoming close friends with Brakhage, Sharits founded two student cinema clubs, screening work by filmmakers like Maya Deren and Kenneth Anger. Echoing the New American Cinema ethos, the films Sharits made during this time were narrative driven with actors and featured themes exploring sexuality, alienation and isolation.

Sharits’ mother committed suicide in 1965, forever altering his life and film work. This was also around the time his son Christopher was born, and both events marked a distinct turning point in his ideological way of working. From that moment forward, Sharits attempted to burn all of his early narrative-style works, mistakenly missing one film, Wintercourse, which fortunately survives as the sole example from that period. Also central to Sharits’ ideological shift in filmmaking was Kandinsky’s 1911 book, Concerning the Spiritual in Art, which helped guide and shape Sharits’ ideas of the “psychic effect” of using colors and the call for a “spiritual revolution” of artists to express their own inner lives abstractly.

In the early 1970s, Sharits was invited by Gerald O’Grady to teach film at the Media Study of Buffalo, a position he would hold for twenty years within a dynamic community of filmmakers that included Hollis Frampton and Tony Conrad. During this period, Sharits began working on gallery installations or, as he called them, “locations.” The extremely intricate and detailed locational works primarily featured multiple 16mm projectors of looped films, highlighting and showcasing the projector like a sculpture in the middle of the gallery. This allowed Sharits to explore and expand the durational aspects of his work in ways not possible theatrically, the loops extending the length of the films to durationsSharits could previously only imagine. Concurrently, Sharits worked on his Frozen Film Frames, a series of works in which strips of film are “frozen” in time and place, suspended between panes of Plexiglas and hung in the gallery to be studied like a painting.

For Sharits, the 1980s began with the death of his brother Greg; he was killed charging the police with a gun in his hand. Already battling the effects of severe bipolar disorder, Paul was devastated and never fully recovered from the tragedy. Throughout the decade, Sharits would complete several films and locational works, but spent the majority of his time painting, a preferred medium he had temporarily abandoned. Indicative of his tortured mental state at the time, his paintings concentrated on medical pathology, disease and decay. Sharits’ interest in the themes of his painting manifested themselves internally as well, as his body began to break down owing to a series of bizarre incidents that included being stabbed in the back and shot in the stomach.

In 1987, Sharits would make his first and only completed video and his final motion picture, entitled Rapture, a quasi music video employing early video technology, complete with scenes of Sharits writhing on the ground in a hospital gown. Six years later, on the weekend of his favorite holiday, the Fourth of July, Paul Sharits ended his life. His work lives on and in many ways is more popular than ever through the efforts of Christopher Sharits and the Paul Sharits Estate, as well as the ongoing work of Anthology Film Archives, whose staff is in the process of preserving his entire filmography, making it available to future generations. – Jeremy Rossen

WARNING: Though designed to produce an effect of internal peace, please be advised that the flickering effects used in these films may cause headaches, nausea, dizziness and (in a small number of light-sensitive people) seizures.