Out of the Ashes – The US-ROK Alliance & South Korean Cinema

October 1, 2023 marks seventy years since the signing of the mutual defense treaty between the Republic of Korea and the United States. Critically reflecting on the ROK-US Alliance signed following the Korean Armistice Agreement, this program features select films of the Korean War and immediate postwar period. On the surface, foregrounding the alliance may seem to highlight the films’ propagandic tone, and hence South Korea’s subordination to the US-led Cold War bloc. The signing of the mutual defense treaty indeed saw the expansion of US military bases and mass media propagation of Americanism, advertising the superiority of “American democracy” in South Korea. And yet, the postwar alliance did not mean a mere injection of Cold War ideologies into the Korean film industry. The alliance marks a watershed in the history of Korean cinema; Korean luminaries appropriated the increased exposure to American popular culture and cutting-edge media infrastructure to navigate South Korea’s place as an autonomous nation state after the brutal years of Japanese colonization and the Korean War. Though the alliance imposed a strict ideological corset on Korean filmmakers, the very promotion of “freedom” as an American value provoked Korean filmmakers and audiences to question the ongoing gender hierarchies, colonialism and ideological divides in the Korean peninsula.

To better understand the distinctive importance of the era the selected films represent, we need to map out the broader history of Korean cinema that is nearly unthinkable without a discussion of the US. Even before The Righteous Revenge (Uirijok kut'o), the very first film made by a Korean director in 1919, cinema as a collective appreciation of photographic moving images was already growing in Korea under the influence of the US. According to historical records, American traveler Burton Holmes made the very first film of Korea in 1901 as part of his larger exploration of the “Far East.” Despite the absence of Korean-made films until 1919, moviegoing started to become commonplace in colonial Korea from the mid-1910s, with the immense popularity of imported American serial films such as The Broken Coin. Until the Japanese colonial empire strictly prohibited the screening of American movies in the early 1940s, Hollywood films occupied more than 80% of the imported films screened in colonial Korea throughout the 1920s and 1930s. Since their very first release, Hollywood films were perceived not only as entertainment for Koreans, but also as a gateway into the culture of the world’s most developed country and hence keeping pace with progressive values and the latest material trends.

While the US had remained for Koreans mostly a symbol of prosperity and progress to be admired from afar during the colonial period, the degree of US intervention in the Korean cultural scene drastically increased following Korea’s liberation from Japanese colonial rule in 1945. At the end of World War II, the US and the Soviet Union agreed to divide the Korean peninsula at the 38th parallel and the United States Army Military Government in Korea (USAMGIK) was instituted in the US-occupied South the same year. Six months into USAMGIK, it passed Ordinance 68, which resumed the import of American films prohibited by Japan and mandated censorship on every film being screened in South Korea under the slogan of anti-communism. At the same time, the US started to invest in producing films specifically targeted to Korean audiences, collaborating with Korean locals and featuring various places in Korea being reconstructed with American support. Such a measure was in accordance with the US government’s interest in “cultural relations” as a tool of micro-level governance of its allies in post-WWII geopolitics from the early 1940s, which laid a cornerstone for the “Cultural Cold War” to come.

Even after the institution of the First Republic of Korea in 1948, the first independent republican government in Korean history, various American films—be they Hollywood, US government-sponsored, or ROK-US co-produced films—were actively promoted in South Korea, based on the two regimes’ shared anti-communist stance. The breakout of the Korean War in 1950 consolidated the weaponization of film against communism already at work in Korea. In addition to strengthening the ideological direction of distributed films, the Korean War provided a solid basis for the US to invest substantially in South Korean film production infrastructure for better localized propaganda. Well before the armistice and signing of the Mutual Defense Treaty, Koreans and Americans were already actively collaborating in film production, boosted by newly built, cutting-edge film studios such as Sang-nam Film Studio founded in 1952.

Compiling Korean films of the immediate postwar periods in the context of the ROK-US alliance therefore becomes a task of unfolding the compressed layers of the two nations’ filmic linkage that preceded the treaty. Focusing on the “unfolding” is crucial in understanding the distinctive historical and aesthetic importance of the immediate postwar films, because of the severe time lag between the imagination and the actual navigation of South Korea’s direction as a modern nation state that started to shrink after Japanese colonization, institution of USAMGIK, and the Korean War. What was the cinematic outcome of the interplay between this long overdue imagination of Korea as a modern nation state mediated via American films, the US-sponsored postwar media infrastructure equipped with cutting-edge technology, and the expansion of US military bases in Korea that brought the once-distant nation into extreme proximity?

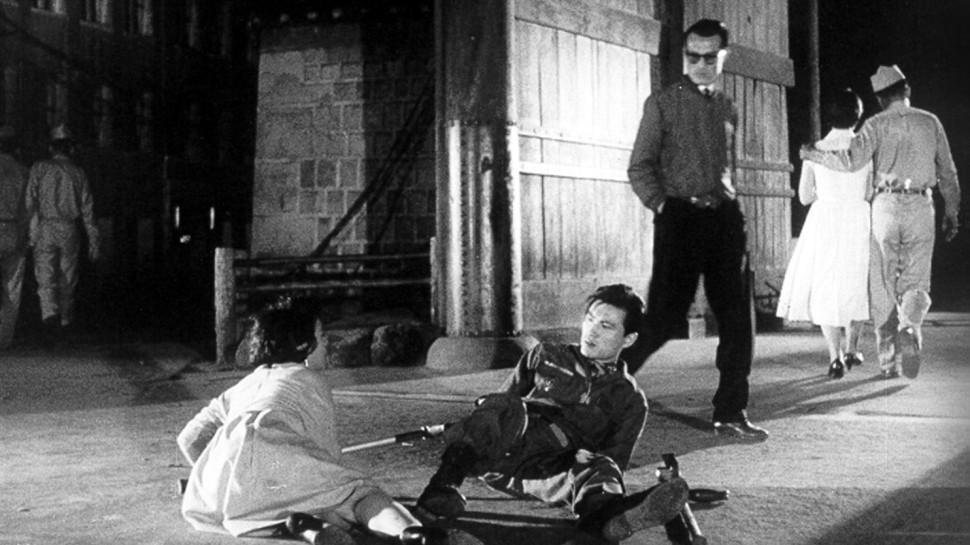

The brilliance of the selected films in this regard is that they remain attentive to the intrinsic fissures underlying the postwar modernity arising from the alliance, while acknowledging the mesmerizing aspect of American popular culture. Despite the depiction of glamorous “American-style” parties, the consumption of American luxury goods, and the glorification of “Americanized” individuals’ pursuit of freedom or love, the films often make sudden transitions revealing the continuing violence and discrimination toward women, the wealth gap under urbanization, intergenerational conflict and colonialism. Often accompanied by radical shifts of light and dark, dissonant music, surprising sound effects and fast cutting, these films do not attempt to suture, but rather foreground a landscape of misalignment. While it is irrefutable that the US has occupied a central place in formulating the mode of seeing throughout Korean history, these postwar films’ strategic employment of audiovisual contrasts reads as a critical examination of a world under the US-led Cold War bloc. – Bu Chan Yong, Postdoctoral Fellow in the Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations and in the Korea Institute, Harvard University