The Films and Videos of Richard Serra

For eleven years (1968-79), the renowned American sculptor and artist Richard Serra (b. 1938) felt out the unchartered phenomenological boundaries of film, pushing it to exciting heights in line with the watershed period in cinema history out of which his film and video work sprung. Hand Catching Lead was made less than a year after the appearance of the Canadian artist and filmmaker Michael Snow’s Wavelength (1967), a landmark film that encouraged Serra to pick up the camera and use it as a device in a series of remarkable studies of film perception: the hand films he made for Leo Castelli’s gallery; a Snow-type work in a New York loft in which a seemingly rectangular window is revealed to be a trapezoid (Frame); ideology-revealing videos in which he parodied and, in his words, “exposed the structure of commercial television”; certain process films that burrow deep into the lives of bridges or of factories that have pulverized the ears and souls of men for untold generations.

In the past—usually at the expense of what occurs in the films—some critics have tried to link the experience, material concerns or aesthetic boundaries of these works to those of Serra’s best-known practice, sculpture. Serra himself has been adamant in his hostility toward such connections: “I did not extend sculptural problems into film or video. I began to make sculptures, film and video at about the same time, so it can’t be a question of developing one form into the other. My involvement with different media is based on the recognition of the different material capacities and it is nonsense to think that film or video can be sculptural.”

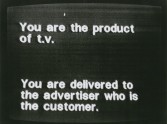

Serra’s films and videos constantly call attention to themselves as films, but always with the political and the artistic on nearby parallel tracks—that is to say, never esoterically. Perhaps the ones that most demand our attention today are Anxious Automation and Television Delivers People. The former is a video whose playfulness contributes to the bitter point: it mocks the synthetic editing techniques used by Hollywood to keep the viewer’s attention span short, to degrade space and to depict time as a grotesquely foreshortened linear stream. It’s a parody of MTV avant la lettre. Serra’s jabs at mass media find their peak in Television Delivers People, a six-minute tape made in collaboration with Carlota Fay Schoolman where what’s being brashly exposed is the gullibility of a populace that doesn’t realize it’s being sold up the creek by the shiny object of a diseased capitalism.

In the two Serra films of the late 1970s, the brash, murderous, expose-the-bastards drive of the videos is mixed with a task-object-setting over a hypnotic, Warholian stretch of time. What distinguishes Railroad Turnbridge and Steelmill is their remarkable historical consciousness. The films have Eisenstein in their DNA (Snow is most present), but it’s the Eisenstein of the unfinished ¡Que viva México!, in which the frenetic montage that links history, art, politics and philosophy occurs inside the viewer’s head, incorporating her range of experiences, his mental montages. The work thus becomes collaborative and open in a way that defies the typical process of presenting movies to viewers—tossed or flung at us, forcing us to engage with a drab, bullying, closed Monoform system that condescends to our intelligence. – Carlos Valladares, adapted from The Art of Perception: Richard Serra’s Films (originally published in the Gagosian Quarterly, Fall 2019 edition)