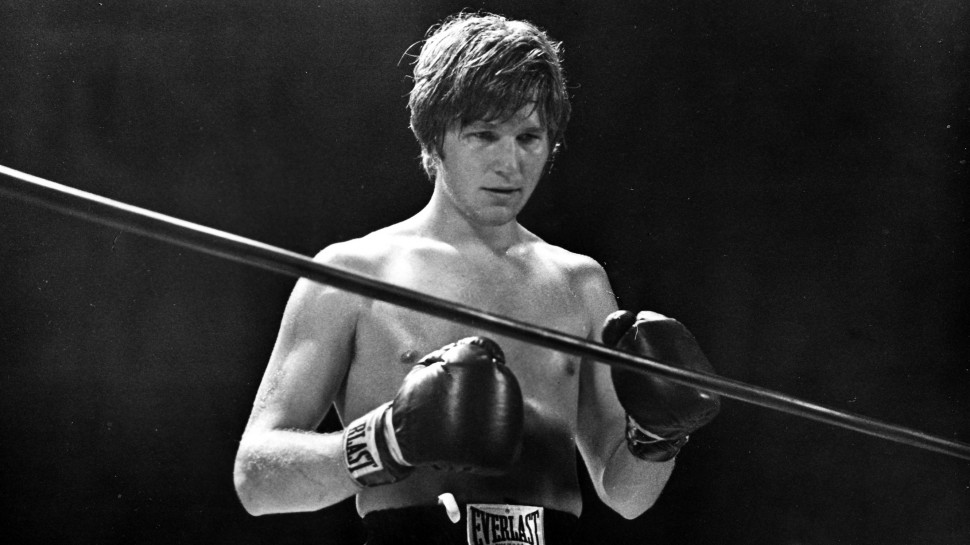

Former boxer Leonard Gardner adapted his own extraordinary novel for Two-Lane Blacktop’s Monte Hellman. When Hellman had to heartbreakingly decline due to contract conflicts, John Huston returned to the arms of critics and the public with the inconspicuous naturalism of his version of Fat City. Acutely rendered shadows and light describe the dingy edges of desperate lives who accumulate around the gym, the bar, flophouses, onion fields – nonetheless flickering with ideas of something grander. A faded, unglamorous boxing film with no precise rises or falls, Fat City instead observes the repercussions of the perpetual expansion and deflation of egos battered by more than fists. Huston – also a one-time fighter – invisibly directs a cast of unprofessional actors and actual boxers with Stacy Keach’s washed up fighter, Jeff Bridges’ conflicted neophyte and Susan Tyrell’s uncannily channeled alcoholic. Both dignified and defeated, they populate a Stockton, California skid row also on the edge of destruction; the very day after the final shoot, large swathes of the film’s locations were razed making way for freeways and redevelopment. Fat City captures moments – both fleeting and eternal – of a particularly American vein of beauty, humor and pain and inscribes them with such unaffected detail the film seems less a projection than an unobstructed view from across the tracks.

Audio transcription

John Quackenbush 0:00

March 31 2014, the Harvard Film Archive screened Fat City. This is the audio recording of the discussion and Q&A that followed. Participating are HFA Director Haden Guest and author Leonard Gardner.

Haden Guest 0:19

Ladies and gentlemen, please join me in welcoming Leonard Gardner.

[APPLAUSE]

Leonard Gardner 0:31

Thank you.

Haden Guest 0:33

Well, thank you for being with us tonight to discuss Fat City and your work on this really wonderful film. I'd like to begin by asking about how you worked with John Huston. I mean John Huston is famous... he began as a screenwriter, and he was famous for his work with great literature and with writers. And so I wonder if you could discuss the nature of your work with him and how closely he was involved in the transformation of the novel into a screenplay.

Leonard Gardner 1:06

Well, one thing I've noticed about Huston's career, when he adapted books, which he did a lot, he stuck really close to the books. I think he really respected novels if they were good enough for him to want to make a picture of them. So he didn't want to take it in another direction. I had already written a draft of the screenplay before he was hired. There was gonna be another director working on it, and he had a conflict with his work engagements, and he had to drop out, and…

Haden Guest 1:54

That was Monte Hellman, right?

Leonard Gardner 1:55

Yeah... And I must say, I didn't feel it was a great loss. Not that I had anything against him as a person or director, but he didn't know boxing, and I had wanted to avoid the cliches I'd seen in lots of boxing movies. And like, you notice that Oma didn't get up in the ring between rounds and, and kiss Tully and say all is forgiven, and suddenly he becomes like a superhero. But this fellow Monte Hellman did want things like that. Somebody suggested—it was either Hellman or Ray Starker his assistant—that when Tully ends up back in Skid Row he's gonna to look at the TV and the bar and there's Ernie fighting in the main event on television. And I had to tell him, “You know, he's not going anywhere. Ernie's not gonna go anywhere as a boxer.” But Huston had been a boxer, and he really knew the scene. And, you know, I was comfortable working with him and having him as a director. I will say this though. He had been a lightweight amateur. He had never fought as a professional, and I can't really remember how tall he was, but he was tall, like… seemed like about 6’2”, 135 pounds. I saw pictures of him, like in a bathing suit when he was a young man and he was skeletal and I thought how could he get…? How could you survive a single punch? But I'd heard that he had been a good boxer. Anyway, he understood it and he was really interested in boxing. And you know, he had his old heroes, there was an old fellow in the gym. When Ernie first comes to the gym there’s a fellow hanging around the gym who says, [IN A GRUFF VOICE] “You lookin’ for a manager?” That guy had been one of John's heroes when he when he was a young man, he met a veteran named Bert Colima who John said would have everybody in the gym, I mean in the arenas when he fought, saying, “Geeve it to heem, Molina!” And that sort of was his nickname, I guess.

Anyway, we understood each other pretty well about the boxing stuff. We had, you know, some disputes over some scenes. And it was about a week ago that I finally realized that he was right [LAUGHTER] in one of these disputes we had. I guess we were already filming... oh, by the way, I saw every day's shoot in Stockton, I was there for the whole thing... And I guess we had done some filming. They really hurried into making this picture. As I said, I had written one draft for the other guy, Hellman, and then they hired Huston, and he invited me over to his Irish mansion in County Galway in Ireland to talk about the script and what he thought it needed and how to make changes. And... I didn't realize this at the time. We’d hardly talk more than about fifteen minutes a day. We would talk about one scene, he only wanted to talk about one scene a day. And if there were scenes that were already in the script, he’d suggest some changes, and then I'd show him the next day how the rewrite of the scene was, and we’d talk about another scene. What I didn't find out until about a year later, when I was in the producer’s office in Hollywood, I was talking to an accountant who worked for the producer about my contract, and I was curious to just see some little thing in my contract. And he went through all these contracts, and he had one for John Huston to make $25,000 to have me as a guest at his mansion, and while he discussed changes that I could make in the script. And when I was there, John had this wonderful collection of pre-Columbian art. He loved his art objects, and there was a dealer in there. He had a dealer come over one day, and they were going through everything and cataloging it and all that. And he admitted that he was going to sell his collection. So he was hurting for money at that time. And anyway, I think he made the picture just about as fast as he could after I was hired, and I was still doing some work on the script while he was filming. And... oh, yeah, I wanted to get around this little anecdote where there were still scenes that we were talking about whether we needed them or not. We had a forty-two-day shooting schedule at 2.4 million dollars. And so you have to decide pretty well what's going to be in the final script so you have time to do it all. And there was a scene that I was always fighting for. And, you know, it was in the draft of the script, and we discussed about four or five scenes, which ones could be shortened and which dropped and…. Then after… oh, he was so slick. After a certain amount of these scenes having been discussed, he says, “Well, I guess that takes care of it. Let's have a drink!” And he poured me a straight shot of whiskey about up to here. [HADEN CHUCKLES] And the funny thing was, he poured one that same size himself. And he drank his down right away, and I worked at mine, you know, for five minutes or something, I managed to get it down. And then he says, “Well, guess we're all done, that takes care of all the scenes!” And I said, “Yeah, I guess so,” and I went back to my hotel room and fell down on the bed, went to sleep, woke up in an hour or two, and I called his room and said, “John, we forgot to talk about the scene, you know, where Tully’s back in his flophouse room,” and he said, “Oh, we're not gonna use that, we don't need it.” And I just thought this scene was so important. And this is the one about a week ago, I realized, was not needed. And that he was right. And he was right because he thought, in a way, of performances, what actors can give, the whole visual thing, and I was still thinking of words. Tully’s manager was going to come to the flophouse and try to get him to go to the gym. And, you know, it's clear to me now that Stacy Keach’s acting and his facial expressions, his body language, they tell you, that he's…. Well, what I realized was, he is the loneliest man in the world. And without a woman to, you know, keep him up he just goes into despair and depression and can't function, you know, he couldn't be a fighter. I think one thing this picture did that other boxing movies don't do, haven't done, is... fighting is kind of, at least in Tully, was a means of becoming whole in a way, leaving the kind of inbuilt failure in him behind, and certainly he never seemed to be a cruel man. And he never seemed to be wanting the title or anything. He didn't have those kind of illusions.

Haden Guest 13:28

You know, this is an unusual boxing film, I think, in so many ways. And one of the ways is, you know, while there are fight scenes, the film is equally about this larger world, right? About the world of the farmworkers and about the bars and about Stockton, California. And I'm wondering if we could talk a little bit about the, you know...

Leonard Gardner 13:50

Have I ever been in one of those bars? [LAUGHTER]

Haden Guest 13:53

I want you know, this is... we were talking before about how, you know, many of these places that Huston shot within would be destroyed just sometimes weeks after the shooting, if not even days.

Leonard Gardner 14:06

And the shooting wasn't even over. I mean, the film wasn't finished. In the very opening scene in that hotel, which was really the best—what they called Skid Row, you know—hotel. It was right on the edge. It wasn't so bad. But they evidently had an understanding with the production company. Because I think it was a day after the last shot in that hotel on the very opening scene. They knocked it down with one of those huge iron balls on a crane. They were sort of following us and knocking down things after they were used.

Haden Guest 14:54

And in terms of you know... you were on the set, and I was wondering if we could speak a little bit about the kind of dynamic on the set and Huston's work with the actors. I mean, I think something else that's unusual about this film is the sense of time unspooling, the sense of just hanging out, the time, you know, at the end, he says, “Can’t you just stay longer to talk?” And this is that need of people, of lonely people, to speak to one another just to hear the sound of their voice. So if we take, for instance, that amazing scene of Stacey Keach and Susan Tyrrell and in the bar where he comes in and discovers her and, and their first real, intimate encounter. I mean, do you have memories of...?

Leonard Gardner 15:39

And they fall in love in five minutes, you mean?

Haden Guest 15:41

Exactly.

Leonard Gardner 15:45

Um… I don't know what you want me to say about it.

Haden Guest 15:49

No, I mean, I'm just wondering if you have any insights into Huston’s work with actors, and especially with this group of performers?

Leonard Gardner 15:57

Yeah… yeah… I wondered about how he rehearsed because he almost never rehearsed out in the open where we could see what was going on. I found out that he had Stacy Keach and Susan Tyrrell rehearse alone, and he didn't watch the rehearsals. They were in a hotel room. And that was pretty good timing that they had in that scene. And they worked on that a lot… how much I wouldn't know. But I could see that he was really an actor's director. Actors must have loved working for him because he didn't micromanage that I could see at all. He just sort of let them do what they would do, and he’d either say, “Let's do it again,” or he'd say, “That's fine.” I think he probably always cast people who had a lot of talent. And he knew they could do it, and he showed them a lot of trust. And I'm sure actors loved that.

Haden Guest 17:27

Now, you were on set. Did you have a role besides that of an observer? I mean, were you consulting on the dialogue and on the…?

Leonard Gardner 17:37

Well, I was still the screenwriter because we were still discussing the script, and there were parts I was rewriting. And they were just nice enough, Ray Stark and Huston, to want me to be there, which is kind of unusual, because I'm sure a lot of producers and writers, I mean directors don't like to have writers around in case, you know, we criticize. I think I was still of use. And I had grown up in that town, and I knew a lot of scenes and places like that great card club in the very last scene. I actually wrote the name of it in in the script of the set because I knew that would work so well. But they were, you know… they’d just come to town. They wouldn't maybe have even found that. I think I was helpful.

Haden Guest 18:51

Now the use of non-professional actors, of locals from Stockton is pretty notable. I was wondering if you could tell us something about this.

Leonard Gardner 19:00

Yeah. There were a lot of non-professionals. All the boxing people, you know, the seconds and the boxers, of course, and the promoter and the guy that ran the bowling alley, he was a boxing promoter in Stockton. They knew how to do it. All the corner men were really corner men. And the wonderful Mexican actor who played Lucero was a San Francisco boxer, a very successful light heavyweight contender, one of the top ten, but I used to work out in the same gym where he was working out, so... I worked a bit with the casting directors, and I knew about this guy. They were trying to get another fighter but his manager wouldn't even let him do it. I think he was afraid that if you let a boxer hang around with Hollywood people you'll never be any good anymore. You just want to play maybe. So anyway, I was able to tell them about this fellow. Sixto Rodriguez, what a wonderful face. One critic said his nose was bent over like a Picasso, which is true.

Haden Guest 20:46

Now, I've heard it said that some of the boxing scenes, Huston would actually just tell the actors to go in there and actually start, you know, actually hitting each other... these weren't doubles in many of the scenes. Is this true or no?

Leonard Gardner 21:04

Apparently that did happen. There's the young Black kid who is talking so big, you know, about if you want to win, you win and all that. Well, there's a scene of him in the gym. He told me… he was scared. He told me that that afternoon, they were gonna do the sparring scene. And Huston told him, I'm gonna let Billy Walker—who was a professional fighter, the guy that was just real slick with his moves—he said, “I want you guys to spar a little then at the very end, I'm gonna tell him to hit you one really hard one.” And the guy was scared. That was he'd never boxed. He was just a kid. And I said, “Oh, no, don't get scared. Don’t worry, John would never do that to you.” But you look at it on the screen and he really, really seems to be staggering around in the ring. So I figured, look like he really did get a real punch, you know, a hard one. There were rumors, you know, that John was—he had a nickname, you know, “the monster”—that he’d done a few cruel things in his career, I guess. I was really looking at the main bouts tonight to try to see… It was kind of convincing. I wanted to see if there were really punches being landed. I saw a few but I don't think they were really hitting hard.

Haden Guest 22:57

I mean, there is something so authentic I think about the fights nevertheless, in the fact that, you know, they're stumbling over each other, they’re...

Leonard Gardner 23:03

Yeah, but see, like in Ernie’s first fight, he's fighting that tall, thin Mexican kid. And they weren't able to make it look very real for a while. And that kid said, “Look, I get hit every day in the gym. You're just afraid to hit me. That's why this doesn't look any good. Go ahead and hit me, hit me a whole lot.” So he faked his punches at Jeff Bridges, and Jeff was hitting him.

[LAUGHTER]

Haden Guest 23:39

Now Leonard, I did just want to ask before we take questions from the audience about Conrad Hall, and just if you could tell us something about the amazing work of the late Conrad Hall on this film, and if you were able to observe or speak with Conrad Hall about his work and...

Leonard Gardner 23:57

Yeah, the thing is, I… you know, they'd let me be on some movie sets of other films and try to get a feeling of what goes on, but I can't say I really understood lighting, so I didn't quite know what Conrad was doing, but he was trying to get something very much like natural lighting. Like the night scenes where the farmworkers are, what they call a “shape-up,” getting hired and going on buses. Those were pretty dark and some outdoor scenes were quite bright, and that's what he was going for, and Huston wanted that too. They really got their heads together on that. They called it “natural lighting,” they were trying to make it look real. Well I told you about the hoe scene...

Haden Guest 25:12

Oh, that was actually to me you were talking so that's actually a good story to share.

Leonard Gardner 25:16

What?

Haden Guest 25:17

That was to me, we were talking about the...

Leonard Gardner 25:18

Yeah, yeah, I told you that, yeah. When the guys are out working in the fields with hoes... I wrote that scene to show the... well, what's considered like the most agonizing farm work you can do. That was working with a short-handled hoe that had about a two-and-a-half-foot-long handle just designed so that the guy chopping at the weeds would be down close enough so he could see the vegetables more clearly, you know, not accidentally cut down some vegetables. And those guys, you know [GRUNTING WITH PAIN], talking about their backs hurting… Well, that scene had been shot with short-handled hoes and actors doing it for fifteen minutes, I think, were having backaches. So that film was sent down as all the film was every night to Columbia Pictures. And the guys in suits—I guess they still wore suits, then? Probably not, Hawaiian shirts or something. They saw that and said, “You can't see their faces.” Or at least they said the people in the drive-in theaters won't see their faces. So they said you have to reshoot the scene with long-handled hoes. And, anyway, a little bit of whatever it is... social protest or something, got left out.

Haden Guest 27:18

Snuffed out of the film. Well, let's take some questions from our audience, if we have any. We have a question here in the front, if you just wait for a microphone so everybody can hear your question? Here it comes.

Audience 1 27:32

There are so many vivid characters in this film, not just in the boxing scenes but in the bars, and male and female, and were those based on people, did you consciously base those on people that you personally knew?

Leonard Gardner 27:49

Yeah, kind of half and half... Composites. I’d just got acquainted with a female bartender for a couple of hours while she was tending bar. And I got the character of Oma, this woman, to the point of saying how her boyfriend had raped her… and anyway she just revealed a fascinating, you know, really over-the-top character. And, sure, I'd been trained by a guy that I kind of halfway-modeled the trainer after, and I knew a main eventer down there in Stockton who was a little like Tully. I didn't realize it till later, I didn't know he'd been a drunk for a while, but one of his buddies turned out to be my sister's boyfriend. And he told her about this guy, who did make a comeback, you know, and did pretty good.... Yeah, there were some real people that gave me ideas, but I just took the ideas and, you know, ran with them or exaggerated them very much, or... And, you know, like Ernie getting the girl pregnant and getting married, that happened to half the guys I knew in high school so that that was an easy one.

Haden Guest 29:45

Other questions? Yes, right here in the middle. Here comes the microphone.

Audience 2 29:55

I was wondering about the last, that great scene where they're drinking coffee at the end. It's not in the novel. And I want to know why and when you decided to end with that scene afterwards.

Leonard Gardner 30:05

Okay, I couldn't hear that. Could you...

Haden Guest 30:08

The final scene… which isn't in the novel?

Leonard Gardner 30:13

Oh, oh, yeah.

Haden Guest 30:16

[INAUDIBLE] … how that came about?

Leonard Gardner 30:20

Well, I can't remember how I ended it. And that first script I wrote, probably the way it ended in the novel, with Ernie alone, hitchhiking back to Stockton, but Ray Stark and his assistant were always telling me, “We gotta get them together at the end,” both main characters. And then I guess, Huston, said the same thing, and I said, “But there's nothing for them to do. The story of the two of them is over,” because Tully has hit a period of stasis in his life. So anyway, I said, “There's nothing for them to do.” And then I got the idea. That would make a scene: two guys… they can't do anything… can't talk. Mostly because Tully has gone into such a tailspin, he’s too depressed to communicate very much. So I thought, get them together... have a cup of coffee... talk... only they don't have anything to talk about. I was discussing the scene a couple of days ago—the scene from the book—and it ended a little more upbeat in the book. Ernie came back from an out-of-state fight that he won. And what he feels, I felt, wasn't an illusion, but he felt... I can't quite remember the words, but it's like he felt “the potent allegiance of fate”—that was the line. He felt… you know, I never said anything about guys thinking they're going to be champs, but that's where I hinted it. [NOISE FROM MIC] (Pardon me.) He felt fate was in allegiance with him. I didn't think fate was, but that was an optimistic little ending for Ernie anyway. It is really a downbeat, sad ending now, I think.

Haden Guest 33:25

We have a mic right here. Gerry Peary. Yeah, the mic is right there, Gerry.

Audience 3 33:34

The gentlemen took my question away about the last scene, which is not in the novel. But there's one other touch in that last scene, which is, I guess the most amazing and the most pessimistic is that moment of racism that Tully imitates the Chinese guy. And that sort of the whole desperation of the movie comes down to that one moment, which is something he would have never done earlier or...?

Leonard Gardner 34:01

I'm afraid your mic’s not carrying here very well.

Haden Guest 34:05

He says at the end and Geary Perry says he thinks that Stacy Keach [INAUDIBLE].

Leonard Gardner 34:14

Yeah?

Haden Guest 34:15

And he says that because that's an extra touch… it gives a sense of desperation. [INAUDIBLE]

Leonard Gardner 34:24

Yeah? You said “racist” though? I didn't think he was racist, but...

Haden Guest 34:31

I didn’t really notice that.

Audience 3 34:32

He’s imitating the guy and I…

Leonard Gardner 34:33

Yeah

Audience 3 34:34

...and something that... yeah…

Leonard Gardner 34:36

Yeah...

Audience 3 34:37

I mean it’s such an un-politically correct ending. It's great. And it's a great little touch to have in there. And I guess that’s my long way to say, was that something you came up with or Houston or am I the only person who’s ever noticed it and been moved by it?

Leonard Gardner 34:50

Yeah. I wanted a very old Chinese guy whose whole life would seem you know, to Tully, to have just gone to waste. And I remember telling one of the casting directors that I wanted her to look for an old Chinese guy. And so she got this guy. He was still working in a bakery. And she wanted me take a look at him and I said, “Well, yeah, he looks okay. But he looks kind of young for what I was thinking about.” [LAUGHTER] And she said, “He's ninety-seven-years old.” [LAUGHTER] So I said, “Okay!” Yeah, somehow or other there was some kind of identification Tully had with him. I think he saw his future maybe.

Haden Guest 36:02

Other questions or comments? We'll take the last question from over here from Mitch.

Audience 4 36:15

Thank you. I'm curious if you know, if you're… well I'm sure you're familiar with the Joyce Carol Oates essay “On Boxing.” If you’ve read it…

Haden Guest 36:27

Essay on what?

Audience 4 35:29

Joyce Carol Oates essay “On Boxing,” if you're familiar, or your opinions about that particular...

Leonard Gardner 36:35

Is that Joyce Carol Oates?

Haden Guest 36:36

Are you familiar with Joyce Carol Oates’ essay “On Boxing”?

Leonard Gardner 36:40

Uh, yeah, yeah…

Haden Guest 36:42

And?

Audience 4 36:42

I was curious, your thoughts about it.

Haden Guest 36:4

Any thoughts you might have on Oates’s essay on boxing?

Leonard Gardner 36:52

On that book?

Haden Guest 36:54

Yes.

Leonard Gardner 36:55

Yeah, well, I thought it was a good book, but not always accurate. I remember when she said boxing was a homoerotic dance, that I thought “Oh, no.” [LAUGHTER] That's something I guess like two sweaty, bare-chested guys in a clinch made her think that, but there’s some pretty desperate stuff going on in the ring, and… I shouldn't pick on her for that line, though. I don't remember much more in the book though, that must have really upset me. [LAUGHS]

Haden Guest 37:48

Well, I think on that note [LAUGHTER], we will end our conversation, this wonderful encounter with Leonard Gardner, thank you so much for being with us.

[APPLAUSE]

Leonard Gardner 37:56

Oh, thank you... Thank you very much. Thank you, thank you..

© Harvard Film Archive

Part of film series

Screenings from this program

The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean

Fat City