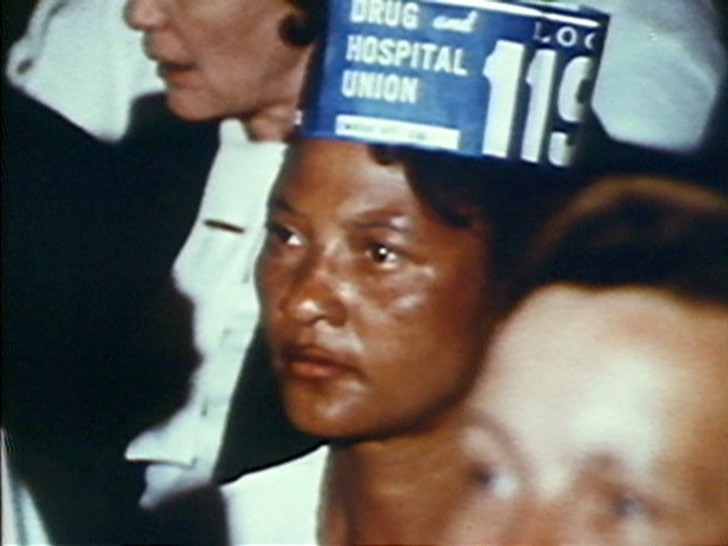

A pioneering filmmaker and producer during a challenging era in American history for both women and people of color, Madeline Anderson confronted astounding obstacles within both the film industry and society at large. However, she remained undeterred and proceeded to make a series of powerful and timeless documentaries. Shot by the Maysles brothers and Richard Leacock, Integration Report 1 features haunting singing by a young Maya Angelou and captures the marches, sit-ins, rallies and boycotts in the months leading up to the first attempt at a march on Washington. A Tribute to Malcolm X, made for Black Journal, discusses the influence of the famous activist and includes an interview with his widow, Betty Shabazz. Anderson’s most critically lauded film, I Am Somebody, documents the struggle of 400 black hospital workers in Charleston, South Carolina, who went on strike demanding a fair wage increase. The film has the distinction of being the first half-hour documentary directed by an African American, unionized, female director. “I was determined to do what I was going to do at any cost. I kept plugging away. Whatever I had to do, I did it,” Anderson has said of her career. The Harvard Film Archive proudly presents the pioneering work of Madeline Anderson with the filmmaker in attendance to discuss her documentaries and the turbulent atmosphere in which these important films were created.

Co-presented by the Hutchins Center for African & African American Research, Harvard.

Audio transcription

John Quackenbush 0:01

November 7, 2016. The Harvard Film Archive screened films by Madeline Anderson, including A Tribute to Malcolm X and I Am Somebody. This is the audio recording of the introduction and the Q&A that followed. Participating are filmmaker Madeline Anderson and HFA junior programmer, Jeremy Rossen.

Jeremy Rossen

Let's try this one more time.

Jeremy Rossen 0:28

Jeremy Rossen, Harvard Film Archive assistant curator. Thank you for joining us this evening on this historic evening of having this pioneering legend, Madeline Anderson, here in our presence. Before I get into the introduction, I just wanted to say a few special words of thanks. So I'd like to thank our co-presenters of this evening, the Hutchins Center of African and African American history, Skip Gates and Abby Wolf. I'd like to thank them for co-presenting this evening. I'd also like to thank Jake Perlin, who organized the wonderful series Tell It Like It Is that happened at Lincoln Center last fall, for a wealth of context information regarding a lot of these films; Walter Forsberg, from the newly opened and wonderful Smithsonian National Museum of American History and Culture, for providing us a brand-new, straight from the lab print of Integration Report 1, so we’ll be the first people to see this pristine print, and a beautifully made DCP scan of A Tribute to Malcolm X. And so we also have this evening Rhea Combs, who’s the Curator of Media Arts and Photography, here from the Smithsonian Museum, as well. So we'd like to welcome her. And lastly, we'd like to thank the NYPL for providing us a 16 millimeter preservation answer print of I Am Somebody, so I’d like to thank them. So, and also just a reminder, when we get started and the lights go down, just to keep your cell phones turned off, so that you don't disturb anyone here in the theater, so thank you. So I’d like to introduce Madeline by just giving a little backstory.

Madeline was a regular filmgoer from childhood. And she recognized early on the potential of the medium of film to educate and inform. As a child growing up in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, in the 1930s, Madeline loved going to the movies. But she was appalled at the way African Americans were portrayed. Madeline says, “I went to the movies every Saturday with my brother and our friends. We packed a lunch and stayed all day. The films we saw didn't reflect who we were. Even then I wanted to see us in films.”

And that's just what Madeline did. She became a filmmaker and television producer who challenged stereotypes and broke down barriers. Last year, the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture recognized her 1960 documentary, Integration Report 1, as the first such film directed by an American Black woman. With the making of I Am Somebody, Anderson became the first American-born Black woman in the film industry union to make a half-hour documentary film. With exceptional determination, Anderson endeavored to tell the stories of people who were not presented in the films she was seeing. As she realized her vision, she broke down barriers of race and gender at every turn.

In 1960, encouraged by an early mentor, documentary filmmaker Richard Leacock, she produced and directed her first film, Integration Report 1. That work, a wide-ranging look at the Civil Rights movement, exemplifies the clarity, economy of means, and political significance that would become the hallmarks of her career.

Anderson was the assistant director and editor on Shirley Clarke's The Cool World before becoming the first Black employee at the television station NET, which would later become WNET. She worked with William Greaves on the renowned NET series Black Journal, where she produced and directed A Tribute to Malcolm X. Anderson left the program to make what has become her best-known film, I Am Somebody, a documentary about the 1969 hospital workers’ strike in Charleston, South Carolina. Madeline's films remain relevant today, for many ways, but, because, as she says herself, quote, “The same problems still exist,” she says. “Housing, education, employment discrimination, and police brutality.”

Madeline has said of her career, “I really don't let gender and race issues bother me. I knew I’d have trouble with both. I was determined to do what I was going to do at any cost. I kept plugging away. Whatever I had to do, I did it.”

Please join me in welcoming Madeline Anderson here to the Harvard Film Archive. And we're very honored to have her here. So, she's here. She made the journey up on the train the other day, and we are very, very honored to have her here. So, Madeline.

[APPLAUSE]

Madeline Anderson 5:18

Thank you. Good evening, everyone. Just a few short words about the films that you'll be seeing. These films were made in the late ‘50s and early ‘70s. And the films were made about the Civil Rights protests, the decolonization of African people and Asian people at the same time. These films show the struggle that was worldwide at that time. And people were determined, there was a new surge in the protests, and events that happened, for things that haven't been solved today. And you will see that these films were, while the people who are the leaders of these movements, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X, and Tom Mboya from Kenya, all were assassinated before anything that they had started was accomplished. And so today, we continue to struggle for civil rights and for decolonization. Now, my story at becoming a filmmaker is a parallel story to the making of these films. So I hope you'll enjoy looking at the films and afterwards we can talk about them.

[APPLAUSE]

John Quackenbush 7:34

And now, Jeremy Rossen.

Jeremy Rossen 7:54

You have such a varied and extensive history of your life and your life's work. But I thought maybe we could start more in the beginning of when you went to NYU and were a student. And while you were there, I believe, that's when you first met Ricky Leacock. And I believe, initially, you were the babysitter for his children. So I wonder if you could talk more about that, because I think through that experience, you became connected with the filmmakers’ group, which was Ricky Leacock, and the Maysles and D.A. Pennebaker. So, but yeah, I think initially, you were an anthropology, or a psychology student at NYU. Is that correct? Yeah. And so how was your, your working relationship with Ricky?

Madeline Anderson 9:05

I was working at Nedick’s. And I was running out of money, so I had to find a second job. And I saw on the bulletin board an advertisement for a babysitter/boarder. And it was signed, “Dr. Eleanor Leacock.” So I applied for the job. Eleanor Leacock was Ricky Leacock’s wife. And Ricky Leacock was one of the world-renowned, was to become one of the world-renowned documentary filmmakers in the United States, and indeed, the world.

At that time he had just finished making a film which made him famous as a cameraman. And when Ricky would come home from locations, he would show the films that he had shot with the crew, and they would sit around and they would discuss it. And I was invited to come and sit in on the discussions, which was a great honor because I was a babysitter. And that's how I began learning about making films from concept to the finished product. I grew up in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, in the 1930s and ‘40s. At that time, the pop-, the Black people there were, like, two percent of the population. And we were forced to live in one section of the town, which was called the Seventh Ward. I lived in the poorest part of the city. And there was one great benefit from that, is that there were so few children there that we were permitted to go to a school that was ninety percent white. And so I got a great education.

Early on, I went to the movies every Saturday. My mother used to try to get rid of us, my brothers and sisters and I, on Saturdays, because that's the day she would do her housework and shop, and do all of that. So we were sent to the movies. And we went to the early shows, ten o'clock. We would take our lunch, which was an apple, and a Mary Jane, a little piece of candy. And we would look at the movies. When the shows were over, we would hide in the bathrooms until the next period began. So, we were there all day, looking at films, and looking at films was one of my favorite things to do, looking at films and reading. Those were my favorite pastimes

But when we went to the movies, we saw Tarzan and the Apes. Gene Autry. No, not Gene Autry, Tom Mix, and Westerns. And in those films, Tarzan and the Apes, where the Africans and the white man would come in and take their property, take their valuables. And I would think to myself, why do we always become the victims? Why was everybody smarter than us? I mean, these were people who had, were kings and queens. They had lands, they had wealth, but yet they weren't able to protect themselves, because maybe they weren't smart. And from that minute on, I tried to find ways to overcome the shame that I felt for these people who were always victims.

And so I started to read, way beyond what I learned in school. And I learned about things that Black people were doing, even when I was growing up. There were singers, there were doctors, there were people who were intelligent. And so that inspired me to want to make films, to show other people that we weren't dumb. We’re smart.

And so, I started out, after I graduated from high school, I went to a teacher's college. I was one of the only- the second Black students who were admitted to this college. Everyone told me that I should be a teacher, because I was always passing around what I, what I learned, I was passing it on to other people. And I was telling them about, you know, how we were pretty good-looking, we were good people. We were intelligent. We were smart. We were good-looking. We could sing, we could dance, we were scientists. And everybody said, you should be a teacher!

So in those days, when I was growing up, the professions that were open to women of color, African Americans and others, were, if you were a teacher, you were held in high esteem. Although I never had an African American teacher, because of segregation and discrimination. And so I tried. I went to a teacher's college. And when I went to, I graduated in the ‘40s from high school. It was after World War II. And because I am Black and female, I was bullied by the young white males who were coming home from the service. And had now, some of them were not rich, but now they had an opportunity to go to college

There was only ever one African American student who was in the college before I came. And she had been there for four years and was ready to graduate. She didn't welcome me either, because I am Black. And she was not. First it was ridiculing, and then when it got to the point where they were throwing things, not to hurt me, but to scare me and to make me unhappy, I thought if they're throwing these things, maybe one day they will hurt me. And so at the end of the first semester, I dropped out. And my idea was to save my money and to leave Lancaster. And that's what I did.

Jeremy Rossen 18:45

And then you went straight to New York from Lancaster.

Madeline Anderson

Say it again.

Jeremy Rossen

You went straight to NYU after Lancaster, is that right?

Madeline Anderson

That's right. That’s right. I had to promise my mother that I would stay in school. And I did. Until after I, my second year, after I had been living with the Leacocks for a year, I got a summer job as, I guess today you would call it, a production assistant. And from that job, I got another job as sort of a person that kept records of what was going on. And I dropped out. I got married, and I stayed in school until I became pregnant, and then I quit. And started working, then, toward making films.

Jeremy Rossen 19:55

And around that time, also, is when you met Shirley Clarke, correct? Or was that slightly after? Because I know that you and Ricky, didn't you start a production company together. Correct? After you'd worked with him for several years.

Madeline Anderson 20:10

All right. Yes, that's what happened. Ricky formed Andover Productions.

Jeremy Rossen

That's right.

Madeline Anderson 20:16

Which you see on the screen for Integration Report 1. And I went to work with him as an in-house production manager. And so I learned the business part of it. As the space that we worked in was a building in which there were four, there were five filmmakers there. Who, if I mention their names, you will know them. Al Maysles was part of the Maysles brothers, they were part of filmmakers. Shirley Clarke, a woman filmmaker and director who directed The Cool World, which is a feature film.

Jeremy Rossen 21:13

Right, we did a program of Shirley Clarke’s here last fall, we showed The Cool World.

Madeline Anderson 21:19

Oh, all right.

Jeremy Rossen 21:21

And for that film you were the editor and assistant director?

Madeline Anderson 21:26

Yes, I made that film after I made my first film, after I made Integration Report 1. Shirley worked in that same space. And so we got to know each other. And she saw that I knew how to make films. And she knew that I wanted to get into the union. And she was making this feature film. And so she hired me to do the continuity. That is, if you see sometimes on the credits on the screen, you'll see “Script Clerk?” That's the same, at that time it was called continuity

I tried to get into that union. Because I'd already made a film. And I knew how to make films. And I, well, let me, let me go back a little bit. After I made Integration Report 1, I wanted to make Integration Report 2, and 3, and so on. And I thought, oh, well, I have a track record. Now I can go and get money or be hired by the networks, or somebody, to do Integration Report 2. They weren't ready for me. And so, I could not get a job at the networks. And I couldn't get a job in the industry because I wasn't in the union. Because to produce and direct a film, you don't have to be in the union. You know, you're starting at the top. But after I saw that I could not get work, or could not get funding to do Integration Report 2, and I wanted to stay in the industry, I thought, now I will get into a union. And that way I can make money and build my career and work myself up to making another film.

In order to do that, I chose the Editors Union, because that was a union that fit my lifestyle. Because I had children, at that time, now I had two children. So if you're an editor, you work on a project, then there's time in between before you get another project, and that was fine. Well, I couldn't get into the Editors Union, because at the time, in the ‘70s, it was early, early, like ‘70s, there was only one woman, one African American woman in the union at that time. And there were only ten women in the local at that time. Out of a thousand people that were in, only ten were women, one was Black. And so, I was qualified. It was a father-son union. So, you see me?

[LAUGHTER]

Madeline Anderson 25:17

I'm not anybody's son who would be in the union.

Jeremy Rossen 25:20

So for The Cool World, then, you were able to work with one of the editors, as kind of like as an apprentice, or to get your experience to get into the union. Is that right? Like through working on The Cool World?

Madeline Anderson 25:35

Working on The Cool World, which was a union production, but Shirley hired me as a script clerk. And then, after the film was shot, she hired me as her assistant editor. And there was another editor who worked on the film. I don't think, see his credit on the film. His name was Hugh Robertson. And he was a very fine African American man, who was a very fine editor. And he and Shirley edited the film together. And I was their assistant. Because Hugh was in the union, he was able to get me an application. And so, now the application, the conditions of the applications were that you had to work for eighteen months before you were going to be able to get into the union as an apprentice.

That's almost impossible, to work eighteen, I mean, for the nature of filmmaking, you work project by project by project. Unless, I guess, you're in Hollywood, then you work on projects for years, because it takes a long time to produce and make a feature film. But in the industry itself, they're short-term projects. You know, you make commercials, unless you work in a production house. So after I got the application, I worked in a number of production houses. And I worked for seventeen months in a number of production houses, before I was called, to eligible to become an assistant editor.

Jeremy Rossen 27:49

Okay.

Madeline Anderson 27:54

When my time was up, I went to the local and asked to be admitted. And I was turned down. There wasn't any reason, it's just that I was not permitted. They were not taking any members at that time. And I had already paid my dues. I'd already filled my requirements. And I insisted that I become a member. And I threatened to sue the union if they didn't let me in.

I got an application from the National Labor Relations Board for their support. And at that time, it was in the ‘70s, it was a recession in New York, and that was the reason that they gave for not letting more people into the union, because there wasn't enough work for the people, they said, who were in the union. But also, they didn't want the bad publicity. So I took the test, or whatever it was. Simple, I don't even remember it, and I was permitted to get into the union. So I got into the union.

Jeremy Rossen 29:29

And through the union, then, did that lead you to get a job at NET, at the television department?

Madeline Anderson 29:33

That’s right. Once I was in the union, now I was eligible to work at the networks, any place that would hire me. And I got a job at, it was called NET at that time, it's now WNET, as a staff assistant. And after working as a staff assistant for less than a year, I became an editor. And I stayed there for, oh, about five years, before Martin Luther King was assassinated. And then they...

Jeremy Rossen 30:25

Well, that's when, like, the Ford Foundation stepped in, and offered a series of funding, which created Black Journal. Which, Black Journal, at the time, was the first television show that they said at the time was for, by, and made for Black people. But at the time when it was instituted, right, the issue was, or one of the many issues in the beginning was, that the executive producer, who made the, who had editorial control of the program, was a white person. And so there was some conflict over the editorial control of things that were being edited. And so, at that point, that's when, fortuitously, William Greaves was brought on as the executive director. So I wondered, I mean, he's such an amazing talent, and you have some interesting things I've read. But I wonder if you could talk about, because I know that was, at the time very controversial, I think, because you didn't go on strike with NET, but you pressured them to have the person resign and have William Greaves step aboard. So I wondered if you could talk about when he first started at Black Journal, and the impact Black Journal and William Greaves had, and his vision for Black Journal?

Madeline Anderson 31:53

Well, William Greaves was a very unusual person to be chosen to be an executive producer of a series, because first of all, he's an African American man. They had never had any executive producers who were Black, male or female. And Bill had, his background was in the arts, he started out as an actor. And then he became a filmmaker for the National Film Board of Canada. As a matter of fact, he was living in Canada at that time. And he agreed to become the executive producer for Black Journal. Well, as soon as Bill took over Black Journal, immediately, the budget was cut. That's the first thing that happened.

Jeremy Rossen 32:54

Of course. [LAUGHS]

Madeline Anderson 32:59

And we were expected to produce professional, innovative programs with a third of our budget cut. I mean, I was told it was a third, I don't know that to be true or not. But it was cut drastically. And because there weren't that many Black people in broadcasts, in addition to producing these films, a monthly show, it was sort of a training ground for young males, young African American males, to become producers and directors of documentary films.

Jeremy Rossen 33:57

Right. Because frequently, didn't they have workshops and things where they did training on equipment, and they placed people in internships, and it was kind of a very hands-on work experience.

Madeline Anderson 34:11

Well, since I had already been working there at NET for years, very few people knew that I was Black [LAUGHS]. Because Black people didn't work at WNET! So when Bill took over, became the executive producer of Black Journal, I requested to be put on the staff of Black Journal. So some people were really surprised that a Black editor had been at WNET for all these years. You know, because no one knew.

Jeremy Rossen 35:01

And so the other people that were on the Black Journal crew at the time was Kent Garrett, who will be coming here to the HFA, actually, a week from today.

Madeline Anderson 35:08

All right.

Jeremy Rossen 35:14

And the other members of Black Journal at the time.

Madeline Anderson 35:13

Well, Kent was a graduate of Harvard.

Jeremy Rossen 35:15

Exactly.

Madeline Anderson 35:16

And he came on as a producer. And there was St. Clair Bourne.

Jeremy Rossen 35:23

Right, exactly.

Madeline Anderson 35:25

Who came, his background was journalism. And then there was another… All of the producers and directors were male. I was the only female that worked on Black Journal, and I assumed the position of being the staff editor. I had a lot of experience of working with NET. And I knew how the system worked.

Jeremy Rossen 36:10

Right.

Madeline Anderson 36:11

So I was very helpful to everybody that was working on Black Journal to make the shows.

Jeremy Rossen 36:20

But you also did, your work, A Tribute to Malcolm X, was the ninth episode of Black Journal. So you did make some of the, besides editing, [INAUDIBLE].

Madeline Anderson 36:33

Well, Black Journal was winding down under Bill Greaves. And so, since I'd been working on Black Journal for the life of that project, I convinced Bill to let me produce and direct a film. Because I had demonstrated to him that I could actually do it, he agreed. And that's how I made Malcolm X.

Jeremy Rossen 37:15

And there was another, you made A Tribute to MLK, as well. There are some other films as well, [INAUDIBLE]?

Madeline Anderson 37:18

Well, I was sort of the tribute person.

[LAUGHTER]

Madeline Anderson 37:24

And so I made a lot of little films when I was working on Black Journal. I didn't get credit for them as producing, or directing, or anything. I was the editor. And whenever Bill wanted a little piece to connect to something to something, he would come to me and he’d say, can you do da-da-da-da? And I was always saying, yes, I could do it. That's why I had the temerity to say to him, hey, Bill, let me produce and direct a film. And that's why it was harder for him to say no. But I did do A Tribute to Martin Luther King. I don't know where that is now. I haven't seen it for a long time. I don't know where it is. And a lot of little things that I did for Black Journal. You see, Black Journal, the body of work was shot on film. And then it was transferred to tape. So in the transferring from film to tape, there were a lot of little connections that needed to be done, which I did, the little, little, teeny little things like that.

Jeremy Rossen 38:40

There's this interesting quote that I read where you talked about when Bill came on, and he said, you said that “he inspired in us that this was our golden age, that this was the golden age for Black input into the media as film producers, directors, cameramen, and all the aspects that go into making films.” And I think, sadly, in some ways, it turned out that Bill Greaves was correct. It really was the kind of the golden age of Black TV and film production. And so, I wonder if you could think about, I mean, Black Journal was such a groundbreaking show, and I think of its lasting impressions, then and now, what you think about because it only lasted for several years, but it's had such a profound influence on culture, on filmmaking. So I wonder

Madeline Anderson 39:31

Well, after Martin Luther King was assassinated, that was the impetus for programming on television for African Americans. It was nationwide. Black Journal wasn't the only show.

Jeremy Rossen 39:55

There was Inside Bedford-Stuyvesant.

Madeline Anderson 39:57

Yeah. There was a movement nationwide to make programs for African Americans, and I hate to use this terminology, but people of color. Now, I don't want to be cynical, but there were audiences out there all the time. I think, as many other people, I'm not the only one that has this thought, this programming, which had its target audience, for Black audiences, were made as sort of controlling. Because you recall after Martin Luther King was assassinated, there was a lot of turmoil in the Black communities. There was looting, and burning, and all kinds of protests. So this was both good and bad. It gave us entrance into the media. And it was the, you know, we stayed home and looked at television. So we didn't go out looting and burning [LAUGHS]. That’s oversimplification, of course, but...

Jeremy Rossen 41:25

Well, I mean, here in Boston, the Mayor had James Brown talk to the crowd in Boston, so they wouldn't go out and riot the day MLK was assassinated.

Madeline Anderson 41:37

Right. Andt that time there was something called Black Power TV, okay?

Black Journal was different from any of the other series. Some of them were entertainment, soul, and the information on Black Journal was more political. And that was because of Bill Greaves, because he was not only an artist, but he was also in the struggle, as we said in those days. And he told us at the time that we should work hard, do the best that we could,

and do something that’s extraordinary, because this was our time for getting into the media.

And this was going to be our golden age. And he was right. Because after the protests and the turmoil quieted down, so did all these nationwide television shows for Black people. They slowly started to disappear. And that's what happened.

Jeremy Rossen 43:15

Yeah, and I think Bill definitely realized the short time that you had, and he wanted everybody to make the most of anything he did, and in very interesting ways. I wonder...

Madeline Anderson 43:32

What about some more questions from the audience?

Jeremy Rossen 43:30

Yeah, I think we should, uh [LAUGHS]

Because I could go on. I have a million questions for you. But I don't want to monopolize you. So we have some microphones in the audience. So if people have questions, raise your hand and we'll get the microphones to you.

All right. In the back, right there.

Audience 1 43:58

Hi. I really enjoyed the films. And if you were a leader of a country, would you do away with religion?

Jeremy Rossen 44:11

She said, um [REPEATS QUESTION IN LOW TONE]

Madeleine Anderson 44:20

No, certainly not!

[LAUGHTER]

Madeline Anderson 44:24

Why would you think so? You can see in my films, sort of the engine that made the movement run was spiritual. And that was, way back in slavery times, that was where we went to talk about stealing away. You know, getting away from the slave masters. That's where we went to plan and encourage each other to freedom. And that's why, in my films, I use hymns and Negro spirituals. Because that was the engine that made the movement go.

Jeremy Rossen 45:32

Take another one in the back right there.

Audience 2

Hi. There was a show in New York for many years called Like It Is, with Gil Noble. And I wondered if you could talk about your views on that show, and how it fits within the group of Black-themed shows in the city at that time.

Jeremy Rossen 45:55

Gil Noble’s show, Like It Is, and how it fits in with the themes of that time and your show. Gil Noble’s show.

Madeline Anderson 46:02

Yeah, no, yeah, Like It Is?

Jeremy Rossen 46:03

Right, how it fits in with the themes of the time.

Madeline Anderson 46:06

And how similar was it to Black Journal?

Jeremy Rossen 46:08

Well, and themes of the time? Is that, other shows as well?

Madeline Anderson 46:13

Well, that was a very long, long running series. You had to congratulate ABC for having such a long running series. I don't quite understand your question. Why could, why did it go on so long? Of course, it was because there was funding. Because one of the reasons were, for the disappearance of the shows on television, was money. It was money. Money from the public, the private sector, Ford Foundation grants. That's what funded all of these shows. It wasn't commercial. It wasn't a commercial success. And because the Black audience was not valued enough, that's why the money wasn't there to continue doing these shows.

Did I answer your question?

Jeremy Rossen 47:34

Oh, we have another one right up here to my left.

Audience 3 47:40

Hi. It’s on. When you made the Malcolm X film, what were your feelings about Malcolm X at that time? And what are your feelings about him now?

Jeremy Rossen 47:55

What were your feelings when you made the film? And are they different now?

Madeline Anderson 48:02

Ah, when I worked on The Cool World with Shirley Clarke, she thought the film was gonna be controversial because it is about gangs in New York City. So in order to be on the safe side, she invited leaders from all of the movements, Black movements, to come in and view the film and critique it. One of the people who came was Malcolm X. He was invited and he came. And that's when I met him. I was so impressed with him. He was brilliant in his articulations, and his thoughts, and the direction in which he wanted to go. That impressed me, and I immediately wrote a treatment, and went to find a fund, the money to do a documentary about Malcolm X.

And it went over like [LAUGHS].

[LAUGHTER]

You know what? Because, first of all [LAUGHS], first of all, it was because he was a very controversial figure. Malcolm X only became as respected, admired, after his death. But while he was living, he was very controversial. And people didn't want to touch him, right?

But if you know anything about Malcolm X, you know that before he died, he left the Nation of Islam. And he formed his own organization. And it was about unity. And it was at that time labeled as “nationalist.” And that's what he was working toward. And he became not an integrationist, and not that he approved of integration. But after the four little girls were killed in Birmingham, he sent a letter to Martin Luther King and offered his help. If you need me, I will help. Because he, at that time, was beginning to see what he called nationalism as unity between all of the struggles and movements for freedom from discrimination and inequality. So that's why I wanted to make a film about Malcolm X.

Audience 3

It was impressive when he said, “I don't know what integration is, I can't define it.” It was like, oh, well, that's a true statement. It's difficult to know, how can you define that word or what it is? It was impressive.

Madeline Anderson 51:49

Integration, at the time I made the film, we were working for not only equal rights in every aspect of society, education, jobs. But as the woman said at the end of I Am Somebody, we gained that recognition, we gained recognition as human beings. And that was a great part of, sort of the idea of becoming a part of the major society, was the goal, because that would be why we would be accepted. You know, we would be integrated into the society. I mean, there were a lot of different meanings of integration, to a lot of different people. Yes.

Jeremy Rossen 53:18

If you want to wait for a microphone, we have a question right there. Actually, I had one quick question. Integration Report, there's a young Maya Angelou doing the singing, as one of the singers, right? So I wondered how that came to be.

Madeline Anderson 53:30

Well, Integration Report was made on a shoestring. I didn't have a lot of money. I worked, my salary, that I made at Andover Productions, I only took a stipend. And my salary went into making Integration.

And I got a lot of support from the Black community, when I was making Integration Report 1. Not funds, but moral support. And people would drop by the editing room to see if I needed anything. And one day, we were finishing up the film, and Maya Angelou came by the cutting room. And she said to me, what do you need? I said, Well, I need some music. I showed her the film, and I said I could use some music right here. She grabbed the microphone and started singing “We Shall Overcome.”

Jeremy Rossen 54:43

Perfect.

[LAUGHTER]

Audience 4 54:51

I wanted to ask how you got involved in making I Am Somebody. If you’ve worked with 1199, if the idea came from Moe Foner, or how that film happened to happen?

Madeline Anderson 55:05

Well, by the time I made I Am Somebody, I had a track record. People knew me, they knew who I was. And they knew what I did in the industry. And I was offered, well, when the strike first started, of course, I started doing research because I really wanted to make that film. And so I did what I usually did, and went to the networks. They knew me at the networks by that time. And I guess they would’ve said, oh, here she comes again [LAUGHS]. And at first, when I started going to the networks, I was met with ridicule. But after I'd been going to the networks for a while, and after they knew something about my work, even though they weren't interested in doing the kind of films that I wanted to do, because, first of all, number one, they said there was not a target audience. And secondly, there wasn’t any money to be made on these films. So when the strike began, of course, I went to the networks. They said, well, it's not something that's going to bring a lot of interest. We have stringers in the field, and they will send, you know, whatever is happening, I said, no, this is gonna be important.

They didn't see the importance. But one of the things that ABC did, I had already written a treatment. And one of the things that they allowed me to do was to use their film library, which was run by two brothers, the Greenberg brothers, who knew me. Because the kind of films that I made if you understand the making of films, it's live action, but it's also stock footage. And that's because I found out if I wanted to make films, I don't have the money. And if something big is happening, I don't have the money to get a crew, and go there, and do this. So in order to do the films, I would write a treatment of the film. And then, when I would see what was happening, I would go to the film libraries to see what they had. And then when I got money, I would go on location, and whatever was happening there then, I took a crew, and we went there, and we shot it. And so that's how I put together the films: stock footage, and it was like making a quilt. You know, you get the pieces here, you get the pieces there, and you get the pieces there. And then you put it all together, and you have a film.

Audience 4 58:34

Did the union help in any way? Did 1199 support it, in any way, financially?

Madeline Anderson 58:49

Say that again.

As you see at the beginning of the film, it says “American Foundation for Nonviolence.” I think that was an arm of the CIO. Now the CIO, if you know history, very interested in the Civil Rights Movement, very much the supporters of the Civil Rights Movement. And when I made I Am Somebody after Martin Luther King was assassinated, that was the last large-scale, big-scale coalition between the Civil Rights Movement and labor. That was it. After that, I think it was for a lot of reasons, but the main reasons were changes in the leadership of the movements.

Jeremy Rossen 59:54

Do we have any more questions out there? Actually maybe wait for the microphone so we all can hear it. Thank you.

Audience 5 1:00:05

Hi, regarding labor, there was a piece where you panned up in a construction crew. And one of the workers was giving, it didn't look like he was approving of 1199.

Madeleine Anderson 1:00:20

What did he did say?

Jeremy Rossen 1:00:22

Construction worker, and somebody who's giving the thumbs-down sign when you come up to the buildings.

Audience 5 1:00:30

Was that coincidental, or was that?

Madeline Anderson 1:00:38

There was a story behind that. One day I was in the editing room, and I get a little package, of, in it was a 400-foot roll of film. When I had it developed, there was, it was from Canada. There was in that footage, these guys [LAUGHS] doing that. There were shots of, you see the women looking out the windows? That was in that roll of film. I never knew who sent it.

[LAUGHTER]

I just got that little package, and I used it in the film.

[LAUGHTER]

Jeremy Rossen 1:01:34

Any other questions out there?

So I was wondering when's your next film coming out, and when can we see it?

Madeline Anderson 1:01:42

Well, in December I'm going to be eighty-nine. I’m try- [LAUGHS]

[APPLAUSE]

I'm trying to convince one of my grandsons, who’s in communication, Joseph, stand up.

Jeremy Rossen 1:02:07

[LAUGHS] On the spot!

[APPLAUSE]

Madeline Anderson 1:02:11

I don't know what the project will be. But I think Joseph and I will do a project together before I'm 100 [LAUGHS].

Jeremy Rossen 1:02:20

You got some time. So yeah, let us know when you finish, and we’ll show it here. So. I’d like to thank you very much for coming out. We have one last thing we wanted to give you as a token of our appreciation for you coming. So Brittany's coming down to bring it to you. So thank you very much.

Madeline Anderson 1:02:34

Oh, thank you! Thank you, thank you very much!

[APPLAUSE]

I want to thank all of you for coming. I really enjoyed being here, and I enjoyed the questions. And I enjoyed your reception to the film. Thank you.

[APPLAUSE]

© Harvard Film Archive

PROGRAM

-

Integration Report 1

Directed by Madeline Anderson.

US, 1960, 16mm, black & white, 20 min.

Print source: National Museum of African American History and CultureA Tribute to Malcolm X

Directed by Madeline Anderson.

US, 1967, DCP, color, 13 min.

DCP source: National Museum of African American History and Culture