The fluidly mobile camera, long a staple of Wenders’ filmmaking, receives its most thorough workout in Wings of Desire, a film whose style approximates the floating, omniscient eye of a celestial presence. Gliding, hovering, and craning around West Berlin in dazzling sequence shots, this camera becomes a conduit to the divine perspective of Bruno Ganz’ Damiel, an angel who quietly, invisibly observes the living alongside fellow immortals, occasionally offering ineffable consolation to those in need. In expressing this state of being, Wenders accomplishes some of the most compelling filmmaking of his career—hallucinatory juxtapositions of classical music with overlapping voices, for instance, and intricate bits of staging that blend point-of-view and third-person framing—but the film ultimately moves beyond a mere angel’s-eye city symphony in exploring Damiel’s muted yearning to join the ranks of the corporeal after becoming infatuated with an exquisite trapeze artist. When the silvery black-and-white of a phantom Germany gives way to the color of a finite, concrete world, Wings of Desire starts to take on troubling existential heft, raising questions about the worth of an existence without sensation or finality.

Audio transcription

Haden Guest 0:03

Good evening, ladies and gentlemen. My name is Haden Guest. I'm Director of the Harvard Film Archive. It gives me enormous pleasure to welcome you all to tonight's screening of Wings of Desire. This is a film, a now classic film, which is cherished by many, myself included. Before I could drive, I had my father drive me all the way to New York to see this film. That's how badly I wanted to see it. And it really did change the way I thought about cinema. And so it gives me great pride to also welcome the film's director, Mr. Wim Wenders, who joins us to present and discuss this remarkable work. One of the high points of his extraordinarily fertile career, and I think, one of the great films of the 1980s.

The shadow of history falls quite heavily across Wim Wenders’ cinema, which in many films seem to be haunted by a still lingering and still unresolved past. By the restless ghosts of times and places long gone, but still vividly remembered. The myths and ghosts of cinema itself are particularly active in Wenders’ films. From the myths of the Hollywood Western, and its imagination of the frontier, to figures like veteran directors Sam Fuller and Nicholas Ray. Or legendary actors, such as Harry Dean Stanton and Dean Stockwell, who literally and poignantly embody the lost world of Hollywood studio era. The still smoldering embers of Hollywood's Golden Age lends a rare crepuscular glow and sadness to Wenders’ films, such as Paris, Texas and Kings of the Road, which are tinged with a sense of loss for a mode of storytelling long since abandoned. But also charged with a determination to reinvent a new visual and narrative language of their own. The ghosts of German history are equally present and active in Wenders’ cinema. Beginning in his earliest works, like The Goalkeeper's Anxiety at the Penalty Kick, Wrong Turn, Alice in the Cities, that together sadly meditate on the difficult meaning of cultural and national memory. Of the scars, fears, and fragile hopes shared by a country dramatically transformed in a remarkably short time. A rapid, and in many ways, traumatic transformation that shaped the imagination of generations and informed the most vital art, literature, and cinema of the period. And yet, Wings of Desire is the film that offers Wenders’ most sustained, profound, and important meditation upon history. The film is haunted by another kind of ghost, by angels. By melancholy men and women with wings who hover over the material world and over the intermingled realms of memory and emotion. They pause to listen and offer gentle solace to the wounded and the frightened. They pause to cast a gaze of tender love upon the children whose innocent eyes are able to see the alternate dimension that these angelic spirits inhabit. Throughout Wings of Desire we are confronted with images and memories of the traumatic past of Germany. At key moments we see visceral archival footage of death and ruins, carefully revealed as a kind of layer, a tissue lying beneath the present moment. The scar lying just below the surface of the city. Throughout the film we also hear memories of the past, most poignantly and most charged in the figure of an old man who embodies the film's political memory. He looks through images by August Sander and searches for vanish sites destroyed by the war. And yet, another layer of history is added, of course, by Wenders’ powerful evocation of a city that now no longer exists: Berlin, divided by the wall.

Well, one of the great strengths, I think, an inspiration of Wenders’ remarkable artistic production, is his rare talent as his collaborator. His singular ability to forge creative partnerships with great artists, often sustained across multiple films. Wings of Desire, I think, is among the most paramount exemplifiers of this important dimension of Wenders’ cinema. And I would point especially to his collaboration with master cinematographer Henri Alekan, with whom he had worked previously on The State of Things. Alekan is, of course, a seminal figure of 20th century cinematography. He helped define poetic realism in France in the 1930s with his work on films such as Le quai des brumes, and then played an instrumental role in shaping Jean Cocteau's masterpiece La belle et la bête, before moving on to work with filmmakers for the likes of Jean-Pierre Melville to Joseph Losey. And as you'll see, an aspect of surrealist fantasy and lyrical poetry also guides Alekan’s imagery and the subtle elastic movement of his camera, which glides and swoons with angelic wings. I’d also point, though, to the remarkable collaboration with author Peter Handke, with whom, of course, Wenders had worked previously. The lyricism, the sustained rigor of the language, are uniquely Handke, and yet given rare cinematic form in Wenders’ hands. I’d also point to the collaboration with Bruno Ganz, the legendary actor, who we’d seen earlier in The American Friend, here as the angel hero. I'm so thrilled that we're not here just to see Wings of Desire. We're here to present the North American premiere of the 4K restoration of the film, which had its world premiere at the Berlinale in February. Mr. Wenders will be giving a short presentation about the restoration, the painstaking work that he did together with his creative team at the Wenders Foundation. I really want to salute them for all the work and effort they poured into this.

But Mr. Wenders is, of course, joining us not just as the extraordinary filmmaker that he is, but he's also joining us now as a Norton Professor of Poetry. And in that distinctive role he will be delivering his second and sadly, the final Norton Lecture of 2018 at 2pm tomorrow in Sanders Theater. You're all welcome to attend. You need tickets and you can obtain them if you haven't already by going to and reading the instructions on the website at the Mahindra Humanities Center. I want to thank the Mahindra Humanities Center for this collaboration that allowed us to bring to Harvard in the guise of the Norton Lecture Series, three extraordinary filmmakers. First, Frederick Wiseman, then Agnès Varda, and now of course the great Wim Wenders. I want to thank, especially, the Humanities Center’s Director Homi Bhabha. I also want to thank its executive director, Steve Biel. And I also want to thank Sarah Razor, who's an extraordinary events coordinator. She's here tonight. Let's give a round of applause to everybody at the Humanities Center.

[APPLAUSE]

I also want to thank and to welcome here tonight Sophia Hofinger, who is on the team of the Wenders Foundation. And I also want to thank Donata Wenders, photographer and another important partner of the preservation projects done by the Wenders Foundation. We will be having a conversation after the screening. It will be between myself and Mr. Wenders and all of you. So please don't go anywhere. Please turn off any cell phones, any electronic devices that you have, please refrain from using them. And now, with no further ado, please join me in welcoming Mr., or Professor, Wim Wenders.

[APPLAUSE]

Wim Wenders 8:06

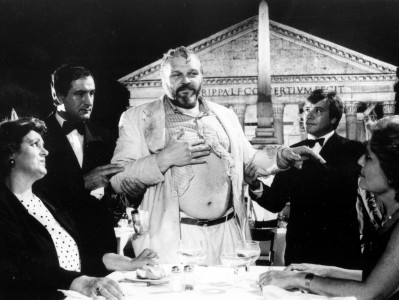

Good evening. Thank you Haden. You're such a poet. You should be holding the poetry lecture. The two times he’s spoken in front of my films I was sad that I had to interrupt it with my poor performance. I'd like to quickly know how many of you have not seen the film? Okay, so there's a number. So you see my leading actor here, and I'm just only going to mention it because I was going to talk a little bit about the restoration as Haden announced. And here's the reason for the restoration in front of you. These wings were not really there. These wings were done in camera, with very old fashioned trick process, done in camera with a semi transparent mirror, so that the wing was 90 degrees away from the actor. And I'm just only mentioning it because Haden already brought it up. I had my cameraman hero to shoot this film. Henri Alekan was 80 years old. He had retired for a number of years already. And when I had the idea that I was going to make a black-and-white film with guardian angels as the heroes, I knew there was only one man on this planet who could shoot this. I just had to get him out of retirement. And I thought I knew how. I traveled to Paris, knocked at his door. His wife opened the door and saw me and said “Uh oh.”

[LAUGHTER]

She saw it coming. I only had to tell Henri two lines. One line was we’re going to shoot the film in black-and-white. I had his attention. Second line, it was gonna be with angels. He was on it.

[LAUGHTER]

Part of the concept of the film was that these angels—I'm not going to talk too much about it—were shot in black-and-white, and that they saw the world in black-and-white. And the rest of the film, the way people saw, about one quarter of the film was in color. So the film was shot both in gorgeous black-and-white, by Henri, who is clearly the world champion of that. (Haden mentioned The Beauty and the Beast and other films.) And one quarter was shot in color, but color occured in each of the seven reels of the film. And that turned out to be the problem, and that turned out to be the reason why this film had to be restored. Not by myself, my films no longer belong to me, nor any other person or any other company. They belong, themselves, in the form of a nonprofit foundation. So all of the income of the film goes into their restoration, which they were quite thankful for. And some of them needed it. Like for instance, Wings of Desire. I want to show you just a little bit—don't worry, it’s not gonna last long—and you will also understand it. [WIM WENDERS PRESENTS SLIDESHOW] You'll see here the color negative that ran through the camera. It's two stripes because... we didn't cut the negative to put it into one stripe. We cut it in A and B, as they say in lab technology, so we could do fades from one to the other. So all the original color camera negative was on two reels, cut in A and B, and all the original color negative that ran through the camera was in color A and B reels. So a number of the effects, like dissolves and fades, could be done in the laboratory and didn't have to be done optically. The next generation saw a copy. An interpositive of all the black-and-white now on one stripe, and interpositive of the entire color. Now making a copy of film is an analog process, at the time. So you put a photograph into a Xerox machine and make a copy. And then you make a copy of that copy. And a copy of that copy. So you realize you lose stuff. I'm going to show you now the third generation of Wings of Desire, was all the black-and-white and color now on one strip. That is the third generation. But into that internegative we cut, also, all the special effects and all the credits and everything, so you couldn't make a print of this. That internegative got us into our first generation interpositive, and that was finally the first combined film with everything in it, except it didn't have any sound. The sound was added in the fifth generation and we made three color internegatives. One was for our French co-producer, one was for our sales in Germany, and one was for international exploitation. And from these fifth generation color internegative all the prints were being made, with different sounds, and not all that different. The film was never dubbed, but the French version has some French language that we didn't have in the German stuff. So anyway, here you have it in conclusion. So, in the end, the print that was also shown for the first time in Cannes was a print of a print of a print of a print. And that leads to an enormous loss of resolution, contrast, and especially, it led to a very pitiful and very painful loss of the quality of Henri Alekan’s gorgeous black-and-white. You see it one more time here. There you see on the left side, when we're shooting, and that negative went into a machine, went into a machine, went into a machine, went into a machine, and finally, was printed. And that's what people saw on the screen for 30 years. Henri was heartbroken over it, because one of the effects of this printing of printing of printing was that all black-and-white scenes had to come from color negative. Actually, his black-and-white had gone three times through color negative. And the black-and-white was no longer the way he had conceived it and the way we'd seen it every night in the shoot, when we’d seen the rushes. The black-and-white had necessarily tinted. It was either a little sepia, a little red, a little blue, but it was never pure black-and-white. Henri suffered greatly from it but there was nothing we could do. That was the condition of making a film in color black-and-white at the time. So today, this is what you see. We took the original negative, and fortunately, we had saved every little bit of it. Every little bit that had run through the camera had been saved. So we scanned every little bit. It was a long tedious process. It lasted, altogether, half a year. We scanned it all, all first generation camera negative that we had exposed on the film, with that 4K scan. And a 4K scan is, in digital terms, the very best possible scan of a negative. You see everything in it. Every grain that is appeared on the original negative is on a 4K scan. From that 4K scan we had to redo each and every fade and each and every dissolve and each and every optical effect. And, as we had everything, we could do it. And finally now, what you see on the screen, as the film will now soon start, we’re through, is the original negative. Closer than anybody could ever watch it. Even Henri at the time, when he watched it, in his hands he couldn't have seen more than what you can see now. So that is my little speech in front, so that we are very proud that the film can now be seen the way it was meant. And that Henri, in the director of cinematography’s heaven, is extremely happy with it. So, oh yeah, you all can be angels by supporting the Wenders Foundation, but that was for a previous manifestation. So, I hope you enjoy the film. I'll be here afterwards, if you're still here. Hopefully some of you, and I'll be seeing you. I have seen the film so often that I will now walk around.

[LAUGHTER AND APPLAUSE]

Haden Guest 18:38

[BEGINNING AUDIO MISSING] … different—the ways in which you've made your films, oftentimes going without a script. And I was wondering in this film, it seems to me, with Wings of Desire, you achieve a kind of lyricism, a kind of openness, that's really quite extraordinary. And I'm referring to the ways in which the angels pass from thought to thought, from poem to poem, from moment to moment, from texture to texture. I was wondering if you could speak about how you found this really profound, yet delicate, rhythm in the film and how you worked, for example, with Peter Handke to achieve this.

Wim Wenders 19:18

It's a little mystery to me...that it all worked out. Because we didn't have a script. What I had, instead, was a big wall in my office with all the pictures of all the places where I really wanted to shoot. And that was the backbone of the film. And basically, my assistant and I, Claire and I, we stood in front of this wall every night and thought, “What are we going to do tomorrow?” And there was endless possibilities. There was endless. These angels, they were dangerous because he couldn't stop imagining stuff with them. And I had a -- well, I had these pictures on the wall and I had something else. I had made an attempt to write a script. And for this attempt, I traveled to Salzburg to meet my friend Peter, with whom we had made a number of films before. And he received me, said, “What brings you here?” I said, “I was hoping we could work on a screenplay together. And he said, “Well, tell me the story.” So I tell him the little story I had. Basically, just the idea that there were these two angels, and one of them wanted to become a human being because he fell in love. And that's already all there was, that story. He listened to it patiently, to my ideas, and in the end said, “I'm really sorry Wim, but you're gonna have to dig yourself out of this one.”

[LAUGHTER]

“And you see, I've started writing a novel, and this one sounds like you have so much in your head already. And it doesn't really sound like it needed a script to begin with.” So he sent me home. And actually, I wrote scenes, situations, with these angels, but in the end, I realized I was going to write for another year and never make a movie. So we started it from one day to another, way too early. On the first day of shooting, we didn't even have costumes for the angels. We started too soon. The costume department was still trying to figure out what to put on these guys. So for the first three days, we shot with all the kids in the movie and all these scenes in the beginning. And each time they had some wardrobe for the two actors, they brought them in, in front of the camera, so we could shoot them, and the kids always laughed, so I knew this was wrong again. There was long white gowns, and armors, and long, curly hair. It was ridiculous, because we tried to be inspired by all the way angels were depicted in paintings. So in the end, we came up for the most simple thing and just put them in the suits. And the little ponytails were the only leftover from all the hairdos we’d done. And then we shot, really, from one day to another. But, I have to say, a big but, as soon as we started, on the first or second day, I got a big envelope from Austria. It was sent by Peter. And he wrote me a letter saying, “I felt a little bad when I left you. And then, when you'd gone, your story stayed in my head, and I thought about these angles and couldn't really– I mean, I think you understood, I couldn't write the script, but there are a number of situations that stayed in my head, and I figured at one point in your film, you're going to have the two of them, sort of, as you described to me, sit for the first time and discuss their routine and what happened to them the day before. So I wrote a dialogue between the two of them. And eventually your angel is certainly going to meet that woman that he falls in love with. So I wrote a dialogue that she could talk to him, first time, and I remember vividly that there's this old guy in your idea. This sort of archangel of storytelling. And I wrote a number of interior voices for him.” And so I had these 10, 12 scenes—not really scenes, dialogues. There was no description or anything. And they became very, very helpful because they were the only thing that was written. So the film, as much as it was flying without instruments at night, there was always a lighthouse in the distance and there was another scene that Peter had written dialogue for, so we flew towards that lighthouse and we landed there and we had a safe day, with Peter's words. And then we took off into the next night.

And on that wall I had a division in the middle. Right halfway through the wall I had a line. And that line was when he was going to become a human being. And there was the right side, when he was a human being. And the left side, when he was an angel. And we spent weeks and weeks on shooting with him as an angel, because we liked it so much, and there were so many more ideas. And eventually, I realized I had one week left of shooting. The money was enough to shoot one more week, and he still was, he still was an angel in black and white. And I had one more week to get him over. So that was as much story as there was. And it's still sort of a miracle to me that it all, in the end, fit together. It was more or less shot in chronological order, that helped a lot.

Haden Guest 25:40

And, I mean, to speak a bit about Henri Alekan’s role in this. The ways in which the camera itself has a kind of angelic presence and abilities. The way it's gliding and swooning and falling. The choreography is really quite astonishing in this film. And to see it on the big screen is even more so. I was wondering if you could speak about—I know with Robby Müller you worked very carefully, earlier on, to sort of storyboard and think about the rhythm. And then later, you moved away from storyboarding. I was wondering, how did you work with Alekan to define these movements, and the rhythm of the film?

Wim Wenders 26:28

Well, we knew we had to move the camera a lot because the camera was, so to speak, the eyes of the angel. And that was a much bigger problem than I figured. Moving the camera was not so difficult. We had all sorts of devices, and cranes, and tracks invented. Amazing machinery to move the camera. That was before there was Steadicams. And, but right away, in the beginning, I turned to Henri and said, “Henri, you know what the problem of the film will be? The camera has to translate what the angels see. That the camera has to be the eyes of the angel. The camera has to learn to see like the angels.” And so Henri looked at me with big eyes, “How am I gonna do that? I think I can make it move.” I said, “No, it's not the movements, Henri. It has to be a very loving look. And again, he looked at me, blank, “How do we teach a camera to have a lovely look?” And then I said to Henri and Agnès, who was the operator –

Haden Guest 27:42

Agnès Godard.

Wim Wenders 27:43

Agnès Godard. “We have to just learn to like so much what the camera sees that we can invest it. Because, otherwise, the camera is not going to show it.” So we tried to really look at everything that happened very lovingly. And in the end, that was the only indication I was able to give to Bruno and Otto, the two actors, because they asked me the same question. “What's our motivation?” I mean, actors, right? They love motivation.

[LAUGHTER]

And they like biographies. But there is no biography for an angel. They don't have unhappy childhood or anything. They don't have a bad father or a bad mother, or whatever. So all I could tell them was just, they love people. And they made the most of the little I could indicate them. It was difficult, at first, to find a way through this universe. I remember, on one of the first days of shooting, Otto all of a sudden interrupted the shoot and said, “Wim, we can't go on. No way.” I said, “What's wrong?” He said, “Don't you realize it's raining?” I said, “Yes, so what?” “Look, my coat. There's all these raindrops. I'm an angel, it can't rain on me!”

[LAUGHTER]

I said “We’re gonna make an exception.” It was a lot of new territory.

Haden Guest 29:20

And, I mean, you spoke about the locations as being so important, as well. And I bring this up as well, because in the ways in which you've also discovered locations that are incredibly cinematographic. I’m thinking of the library, especially. This extraordinary space. The Bibliotek zu Berlin, where— and again, with these sort of portals going up to the heavens, in a way. And I just, I've always admired and been just in awe of the way that you decided that the angels would be, sort of, bibliophiles. Or they're lovers of the library. Lovers of this memory, of this knowledge and I was wondering–

Wim Wenders 29:59

They should come to Harvard.

[LAUGHTER]

I've seen some of your libraries. Amazing, yeah. It was one of the crucial questions. Where do they live? And of course, we first thought of all sorts of churches and of the Cathedral of Berlin and stuff. And then I didn't really want that religious connotation, so we looked for other places. And for a while, I seriously wanted to put them on the Brandenburg Gate, but that was still in the east, and that was out of the question. I tried hard. I went there and I tried hard to talk to the minister of cinema. But as soon as I realized we didn't have a script, and that our leading actors were archangels he–

[LAUGHTER]

He said, “You are not going to shoot one single scene in the east.” So that was out of the question. And eventually I just tried to think of the places I like myself. And the National Library is one of the most beautiful places. Designed by a great architect, Hans Scharoun, who also built the Philharmonics. He was one of the architects considered degenerate by the Nazis, so he couldn't actually work for 15 years. And this was one of his first major buildings. And it was really built with such a love for the act of reading, and with such a respect for books. And it’s almost like a cathedral of reading. And we were very happy. The only drawback was we couldn't shoot in there, because we didn't get a permit. And I really tried hard and it was out of the question until a very, very gentle soul said, “Theoretically, you could shoot every Sunday morning, because we only open at 12. So that's what we did, every Sunday for the entire shoot. We got up very early, five o'clock, and we shot in the library from six to 12. It became our ritual. Our mass was at the library. Every Sunday. And then we had our day off on Monday or so. So, we really got used to the building and really liked it so much.

Haden Guest 32:22

There's something that I’ve been thinking, after seeing Paris, Texas last night, and now this film. There's a sort of mystery that they share, this enigma about the status of certain characters. In this film I find myself wondering if the character of Marion is an angel herself or not. In the same way, I find myself wondering if Harry Dean Stanton is actually, if he's some kind of apparition himself. Everybody assumed he was dead, he seems to come back. He seems to recede and disappear. And I was wondering if you could talk about this presence and absence that these characters at times hover between. Particularly the figure of Marion. The way she looks at Bruno Ganz at the beginning and we realize later that maybe she does in fact, see him, right? She has these earrings that look like wings and–

Wim Wenders 33:18

Yep, she does look him into the eye, at least for a second he believes it himself. And then, of course, she looks away again, so... There is a connection, definitely. [LAUGHS] I figured it had to be a woman who can fly. For the angel to the fall in love with. I know it’s probably a very stupid idea, but I liked the idea to include the circus. And circus people are so mysterious, anyway. And there's so much at stake. And they're so alone also, sometimes. Most of the circus people I met were very lonely people. So I was very attracted to the circus and she sort of learned to do the trapeze. From the moment we decided to make that movie to the first day of shooting, she didn't even have two months. And she had never been in a circus on a trapeze, and she was completely obsessed with the idea that she could do it herself. Or she was horrified by the idea that she would stand there and then I would cut to some stand-in. And so she found herself a Hungarian trapeze coach. And they worked every day. Eight hours a day. And at the end, when we shot, she was able to do all of it. There's not a single second of a double (somebody standing in), and at the end of the movie she had lots of offers to appear in circuses.

[LAUGHTER]

But she refused, because it was too hard work. It was eight hours a day to stay in form.

Haden Guest 35:10

But was this at all in your mind, that she might have been an angel beforehand?

Wim Wenders 35:16

No, that entire idea of a former angel was an afterthought. The whole idea, like Peter Falk’s–

Haden Guest 35:28

Peter Falk was an afterthought?

Wim Wenders 30:30

Peter Falk was an afterthought. We had already shot for two weeks. And there was another night of Claire Denis and myself in front of a wall, and we pondered what we would shoot the next day. And then I remember I turned to Claire and said, “Don't you think our film is too serious? Don’t you think the angels take themselves too seriously?”

[LAUGHTER]

And she said, “Yeah, you have a point.” I said, “We need to introduce another character, somebody lighter, somebody– What do you think? Somebody who has been an angel like Damiel and who knows experience?” And she looked at me and said, “Oh, wow, that's a good idea.” And that night we cast Peter Falk, by deduction.

Haden Guest 36:18

It just came out of thin air?

Wim Wenders 36:20

No, we just thought, “We need to find somebody.” I liked the idea that the former angel would be known to everybody. I thought that it had more potential if it wasn't an unknown former angel, but somebody everybody knew. And then we started to think, “Who is known by everybody and who would be believable as having been an angel?”

[LAUGHTER]

And by deduction, we ended up with Peter Falk. In the end, we realized there was no other human on the planet.

[LAUGHTER]

And luckily, I had John Cassavetes' phone number, because we had met before. And as it was at three o'clock at night in Germany, but something like nine in the evening in Los Angeles, so I called John and said, “John, can you help me out bigtime? I need to get in touch with Peter Falk. Can you help me? Give me an agent or his secretary or something?” He said, “No, no. I’ll give you his own number. He'd be happy to hear from you.” So, I wrote down the number, 310 number, and I hang up and I looked at Claire, and we realized we had nothing to lose. We had everything to win, but nothing to lose. So, I picked up the phone and dialed that number. And I hadn't really thought what I could possibly say. Yeah, I thought it's gonna ring and then there's going to be an answering machine. It's going to be his secretary, so I have time to think it over. And as soon as it rang on the other side, the phone was picked up as if he had been sitting–

[LAUGHTER]

–with his hand on the phone. “Yeah!” was the unmistakable voice. The man himself. And then I stuttered and I sort of explained myself. And then he interrupted me and laughed, and said, “Are you serious? You're calling me from Berlin and you're in the process of making a movie and you’re adding a part that is not written and you’re calling me?” I say, “Yes.” “What is the part?” I said, “A former angel.”

[LAUGHTER]

And he laughed for about 10 minutes. It was a very expensive call.

[LAUGHTER]

And then he only said one thing, “I’ll do it. I've done my best work this way.” That was his line. And then I spoke to his secretary to arrange for his flight the next day. And he was there two days later. Yeah, he stayed for two weeks. And we wrote his part in one night. And he loved improvisation and he was thriving on it. And anything that was written bored him, but he would rather do it from scratch. So we had a lot of fun. And our two angels got very scared of him, because they couldn't really improvise. It wasn't a German thing, you see?

[LAUGHTER]

And he improvised the shit out of every scene.

[LAUGHTER]

And they got so scared, but they loved him. They really loved him.

Haden Guest 39:40

Well, I mean, the film is unimaginable without Peter Falk, of course, so I'm just blown away by this fact that it comes as an afterthought. But also, just the whole idea of the film within the film, because you know, this film is constantly finding portals into the past, and one of them is this film in which we see, you know, the Nazi era sort of emerging, as though in this strange form of this, almost like Curt Siodmak story, of like the two Hitlers, and things like this.

Wim Wenders 40:16

Stupid.

[LAUGHTER]

Haden Guest 40:18

[LAUGHING] But again, adding the humor there. But I was wondering if we could talk, though, about the relation to the past and because the film is so courageous to really address, right on, a topic which hovers over your other films, which is the past of Germany. The burden of history. This burden of memory. And I was wondering if you could speak about the challenges for you to address this. But also for the challenges for this film as a production. To be making this film at this particular moment.

Wim Wenders 40:56

It was important that there was references to the past, into the "hour zero" of Berlin. And that was one of the initial ideas, that the angels were so attractive, because their characters would allow us to also go vertical in time. So it was clear that I wanted to, somehow or other, sort of cut across the city also in time, and go back to the most horrifying moments of it. When it was completely destroyed. And I didn't really know. Peter was the opening for that. Because when he was there then, [UNKNOWN], and he said, “Well, I gotta be working on a movie. Otherwise, how are you gonna establish me?'' And I said, “Yeah, I thought about that. Maybe you’re a detective in an American production, here in Berlin?” He liked that idea. And then we thought, “Well, maybe this is the chance, and we invented this flimsy—it was a flimsy idea— that he was an American detective working, somehow, in Germany, in the last year of the war. Looking for somebody. It was flimsy, and we didn't make much of it. But we found this incredible location. This bunker, that at one place in the ‘60s, they had made an attempt to destroy it, because it was a big, big lump of cement in the middle of the city. And they had filled it up to the rim with dynamite and they tried to blow it up. And it hadn't moved. Except that two of the walls in the center, through the ceilings, had broken. But other than that, they had given up any attempt to make it disappear. And I'd always seen it. It was built in ‘44. And I always wanted to go inside. And then, we realized this was maybe the possible location for Peter’s character. And Henri was scared, because he said, “There's not going to be any electricity in there.” And he was right, it was completely empty. And we had to send several electrician crews, two days and two nights, in order to even rig it. And then it turned out, of course, to be such a perfect background for our story. And the movie that dealt with the history was sort of, at least, allowed some sort of glimpse of the "hour zero." And then there's another scene, when Otto jumps off the column and falls into time and remembers the air raids and stuff.

Haden Guest 43:47

Let's maybe take some questions, comments, from the audience. I see some hands up already. And if you’ll just wait for the microphone to come to you and everyone can hear. This gentleman right here, please.

Audience 44:04

[AUDIENCE SPEAKER BEGINS TO ASK QUESTION WITHOUT MICROPHONE TURNED ON] So last night I was hoping to ask you about the imbalance between watching a film very critically, and trying to [INAUDIBLE] everything that we can. And kind of reacting very emotionally [INAUDIBLE]. And now [INAUDIBLE] Wings of Desire, I mean, the relationship between American filmmaking and European. So you have, in the case of Paris, Texas, a very American film, that I think works so brilliantly [INAUDIBLE] where you sit, and you let yourself get invested in the characters. You have this incredible, emotional payoff at the end. Whereas, with Wings of Desire, it seems much more academic, intellectual. You know, I still had this incredible emotional [MICROPHONE TURNS ON] experience by the end. It seemed like there was much more very blatantly there for you to chew on, intellectually. And I was wondering if that was something you had in mind, and you were thinking about, in the relationship between America and Europe. But also, if you can just speak on that generally.

Haden Guest 45:02

Did everybody hear the question?

Wim Wenders 45:05

First half, maybe.

Audience 45:07

Should I go again, or?

Haden Guest 45:09

I'll try to summarize: the gentleman’s meditating on Paris, Texas and Wings of Desire as operating in two different modes. Paris, Texas being more like a, quote unquote, American film, where it builds steadily and then ends with this incredible sort of emotional release. And whereas Wings of Desire, on the contrary, seems to him, to be more of a, quote unquote, intellectual film, and to be more your, quote unquote, European mode. And just asking to reflect on, maybe, this sort of larger difference. In terms of narrative arc. In terms of emotional resonance. In terms of rhythm. In terms of tone.

Wim Wenders 45:54

Both films have one thing in common, completely. They are invented by their landscapes. Paris, Texas really was designed to film in the West. And I found the perfect partner in Sam Shepard, to write a story for the American West. But first, there was these places. And I was born with the idea to make a film on my hometown of Berlin. I wasn't born there, but I always considered Berlin my city in Germany. And I wanted to make a film in and about Berlin and didn't have a story. I just knew I wanted to explore the city as deeply as possible, and was desperately looking for some characters that could populate the city. And as much as Paris, Texas had been satisfying, and as much as the film had allowed me to come back—because I was scared to come home without having to show anything for the eight years I spent there. And finally, Paris, Texas was my big relief. I could come home. I had something to show for. But then, the problem was that afterwards, everybody wanted something like it. Because it was really the very first time I had a commercially successful film, and everybody then said, “Well, Wim, finally, after all this meandering, you know what to do.” So, and that was a heavy duty pressure, and it made me realize, the last thing I was gonna do was anything like it. Please. And it took me a while. I really had to walk away from filmmaking, for almost three years. And to overcome the hurdle of the expectation. And then I thought, I was gonna do the very opposite. It's gonna be something in Berlin, that I knew. And eventually, by lack of any other ideas for any other characters, I came up with these guardian angels. And actually, sometimes I woke up in the mornings thinking, “You're totally crazy. A movie with angels is not like you.” But then I stuck to it, and there were extremely helpful– And actually, the more we shot, the more unbelievable it was that we continued shooting, that sort of everything worked out. That, I felt, the angels really had their fingers in the whole deal. And I was scared when we first showed the film. The film had not been seen by anybody, nobody, except for by the crew and by my editor. And by Henri; we saw the rushes every night. But nobody knew what I was doing. And we went to Cannes and I was pretty sure that they were going to rip me apart. Because I felt a little bit like you, the film is probably way too intellectual and too spiritual and overloaded with stuff. And so I thought they were gonna kick my ass there. But then they liked it. And it was the very opposite, in terms of the making. Paris, Texas was such a river of storytelling. Once we had that character and we had his drive to find that woman and his son, it was like the film was a little boat on a big river. We didn't have to do anything. Just keep the boat on the river. And the movie had that flow. I almost only had to make sure that we wouldn't drift into the side waters or something. And Wings of Desire was only side waters. There was no narrative flow, apart from Damiel's drive to become a human being. But as I said, we were so in love with his angel existence, we almost forgot all about it.

Haden Guest 50:21

Let's take that question there, on the side, Andrew.

Audience 50:25

Thank you so much. Huge fan of your movies. One thing that I've loved—you know, I came to yesterday's film, as well, for Paris, Texas—and it’s learning from hearing your stories that you even used the word "guerilla filmmaking" to describe your style, at one point. Of this sort of ‘"run and gun" approach to making movies and thinking on the fly. And often, when I watch your movies, I would never think to describe them as guerilla filmmaking for some reason. It seems like every shot is this thing that's very planned out, and there's this sense that, compositionally, you think very far ahead, almost. Or that's the impression I always had watching your films. And I was wondering how, you know, just this process, how you are able to control, I guess, the composition and a lot of these things we see visually, in spite of the fact that you're thinking very much in an improvisational way, I guess.

Wim Wenders 51:27

In the first few years of filmmaking, I was very worried about the language and about composition. And I could not go to sleep in the evening without having like a piece of paper and very simple, primitive little drawings. Drew the frames for the next day. And when I knew them, I felt I could handle the day. And that was my way of shooting. And even when we shot without a script— like some of these films, even the early ones were done without a script—I still needed to have this... I had this urge to know how these shots were going to look. And I ended that very consciously with Paris, Texas, and told Robby, “We're not going to do that. We're never gonna know what we're going to do. We will not know a single frame when we come to the set in the morning.” Because I felt I owed it to the landscape, to be inspired by it and not impose any framing. And it actually worked. It worked easier. I went to bed very early, because I had nothing to do for the next day. But we always got up very early to get the early morning light. And I realized that as much as I had worried about framing and about style and all of that, I didn't have to, because I realized I had something I could rely on. And that was not film history, and it was not anything I learned in film school. And it was nothing I knew from the history of photography or filmmaking. I realized everything I knew about framing was from painting. And that had been my big inspiration as a little boy and all through childhood and later on as an adolescent, I always had wanted to become a painter. And painting was my big influence, and that I knew so much more than about movies. And when I learned about movies, it was way too late. I was already 18 or 19 or 20 years old, and you don't learn that much anymore. Probably. And so I realized, when I relied on a sense of framing that I knew from painting, it just came all by itself. And Wings of Desire, we didn't ever think about framing. I mean, it was about the places I liked. And once we were at the place, I knew how to film it. But I didn't have to, sort of, intellectually think it out. And a lot of the scenes were only done in one shot. And every now and then there's the opposite, there's lots of shots. I was always much more from the guts, and never any intellectual process, like it had been so much in the beginning.

Haden Guest 54:30

How does photography play into this though, too? Because, well, it seems photography is your other vocation. In the ways in which, you know, for Paris, Texas, you spent a long time photographing these places. Does that give you the sense of the space? The sense of the composition? The sense of the rhythm of a place?

Wim Wenders 54:53

It was the same thing. It was as if my body knew it, and my body sort of knew framing. I always work with fixed lenses also, in movies, never with zoom. So you have to walk towards it or you walk away from it or you walk parallel. But the sense of framing is something that I knew from Vermeer and Hopper and Beckmann, and all these painters I had studied and liked. And they had taught me everything there was to know about where to put the camera.

Haden Guest 55:27

Right. Andrew, let's take this gentleman up in the very front.

Wim Wenders 55:38

You have written so much on your blog, I'm impressed.

Haden Guest 55:41

You have a very full notebook here, yes.

Audience 55:43

I don't usually. Something about your words made me. Are there–

Wim Wenders 55:48

Now I'm scared.

[LAUGHTER]

Audience 55:53

Are there angels in your own ontology? Unphysical beings with consciousness. And if there aren't, or even if there are, what do your angels mean? And how did you conceive this beautiful, extraordinary notion of angels wanting to relinquish their angelic status to become human?

Wim Wenders 56:27

I don't even think it's an idea I had. Somehow I always thought it was public domain, at least, as certain myth about—well, all the Greek stories are about gods becoming people. And I always took it for granted that many angels would have wanted to become a human being, because it was great to live, I thought. And I always imagined eternity as being incredibly boring. But that's only myself. So when I started this film, I really thought of angels as metaphorical. And I couldn't really believe in them. But I believe that angels made sense as sort of a metaphor for the better human beings we all would like to be. Or maybe metaphors for the children we still have inside ourselves, that we once were. And only in the course of filming I started to think differently about them and really take them much more seriously. And especially their ability to like us I took very seriously, so maybe there is some leftover of the metaphor of the better people that they were. And I must say, I did meet some angels in my life. Not only former. They are peacemakers to begin with, and I think that's the first quality they have. That they would like to instigate peace. But I could ramble on forever, sorry.

Haden Guest 58:23

How about Walter Benjamin's “Angel of History”? I mean, I know Benjamin is quoted in the library, and that's something I know many have referenced in thinking about this film.

Wim Wenders 58:35

The “Angel of History” by Paul Klee that was bought by Benjamin... I don't know if people know that.

Haden Guest 58:41

The monotype that he owned.

Wim Wenders 58:42

Yeah, he owned a monotype. That was the first page in my script.

Haden Guest 58:46

Ah, it was? Okay.

Wim Wenders 58:47

A representation of that “Angel of History.” And whenever I didn't know what to shoot the next day, I just looked at it. At the “Angel of History." Something came. He blew something into me.

Haden Guest 59:05

We do see Bruno Ganz blowing with his [INAUDIBLE]. Yes.

Wim Wenders 59:07

Right. And it's true that there is a little reference to the Paul Klee, appearing in the library. Some voice says it, yeah.

Haden Guest 59:18

The gentleman in the glasses, here. [INAUDIBLE]

Wim Wenders 59:24

Coming at you.

Audience 59:28

Thank you, so much. It's a little bit about when you mentioned, what you called your home city, Berlin. And I want to ask a similar question, but a different part about the city of Berlin. And the second time I watched this film, tonight, I'm left with some kind of an opposing set of feelings. One is feeling of completeness. And the other one is just its opposite. And what I mean by that is, maybe, it's about the German title as well. Sky over Berlin. So when you think about the German title, you have this completeness. And this completeness is also manifested by all these people we hear in this film. The immigrants, as well, and also people in the Nick Cave concert. But when you look at where the film is taking place, actually, it is taking place in a divided city. So we only get a very impartial picture of Berlin. At least that's how I saw it. And that's why I said I'm left with a feeling of incompleteness, as well. So I would like to hear a little bit about your feelings about shooting this film in a divided city. Not being able to bring East Berlin into the picture.

Wim Wenders 1:00:48

It was painful. And I did make a serious effort to shoot in the East, because Paris, Texas had been one of the few West German movies that was actually distributed in East Berlin. I don't know why, they thought it was somehow an anti-capitalist movie or something.

[LAUGHTER]

Actually, it was shown all over Russia, with 3000 prints. I don't know what got into them. But it had led to my meeting the minister of cinema, who said, “You can always come if you want to make a film here in East Berlin.” So I had high hopes when I started to conceive of Der Himmel über Berlin, that I could shoot it in both parts of the city. And I did visit the minister. But as soon as he found out it was about angels it was hopeless. There was no way. I remember the moment when he interrupted me, when I was telling them my story and he said, “So they're invisible, huh?” I said, “Yeah, they can cross any wall.”

[LAUGHTER]

Yeah. They can cross the Wall. And that was the end of the conversation. So that was painful. I really had hoped that the angels could appear in both. And now there's only three or four shots that we shot clandestinely in East Berlin with an East German cameraman, who got some film from us and he shot some subjective point-of-view, traveling through East Berlin. Through Prenzlauer Berg. And we had to smuggle the film back under the seat of an old VW Beetle. So there is a number of shots, just four or five. And it was painful, but then again, Berlin, West Berlin, was such a microcosm and such a unique planet by itself. And the other part of the city was the other side of the moon. So when I realized I could only make it in West Berlin, I had to live with it. And West Berlin was really an incredible place and was full of a zeitgeist of its time, and there was so much melancholy. And all these people, I mean, this was the biggest Turkish city outside of Turkey, already then. A lot of people from all over the world ending up in Berlin. Also young men, because in Berlin you didn't have to go to any military service, for instance. It was a very peaceful city. And these, all these crazy Australians ended up there. Both bands in the film, Crime and the City Solution, as well as Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds, were the leftovers from Birthday Party, a big Australian band. And they all ended in Berlin and had become local heroes in Berlin. So the city, in itself, was only half the city, but it was still enough to thrive on and to make a movie with. And we had to build the bloody wall, because we couldn't shoot there. So I had to build this stretch of the wall. We had to build 200 yards full of this– Two walls, it was two, and the stripe in the middle. And the tower and everything. We had to build this stupid thing, not knowing that two years later, it was all gone. Two years later, none of us would have thought that possible. It was so solid. And perestroika was just in its beginning, when we started to make the film. And so, it was a sheer mystery that, two years after the film came out, not only angels could walk across the wall. It was insane. And the film has so rapidly, then, become a historic document. Which, of course, was not the intention when I made it. It is now.

Haden Guest 1:05:01

Yes. The woman in glasses, yes.

Wim Wenders 1:05:04

Yes.

Audience 1:05:06

Hi, can you hear me? So I have two detail questions. The first one is: when Damiel and Cassiel are in the convertible at the beginning. I think you said this is one of the parts that Peter Handke wrote? There's one line where he says -- when he's thinking about the things he could do as a human, Damiel, he says, “Ein Kind zeugen, ein Baum pflanzen,” and I wondered if that was a reference to Ingeborg Bachmann's The Thirtieth Year?

Wim Wenders 1:05:33

I guess so. Yes.

[LAUGHTER]

Audience 1:05:35

Okay. Yeah.

Wim Wenders 1:05:37

There's also reference to Philip Marlowe.

Audience 1:05:39

Oh, okay.

Wim Wenders 1:05:41

Like feeding the cat.

Audience 1:05:48

And the second would be: I always wondered where the circus scenes were filmed in Berlin. And what part of the city that was.

Wim Wenders 1:05:53

That was one of the no man's land. The wide open spaces. It was in Kreuzberg. Berlin, at the time, had hundreds of these open squares, with just the paths, self-made paths leading across them. It was ideal for kids. It had endless space. And it’s the only city I ever knew that had so much open space in the middle. And now most of them are closed. So this was in Kreuzberg. And already, the idea of the circus came up because Berlin had all these territories where just any circus could just put their tents up and there was always a circus in Berlin. At any given moment, there were two or three circuses, because it was an ideal circus town. They had all this space. So that one was in Kreuzberg.

Audience 1:06:51

Sorry, I just have to ask this, because my question is related to that. There's a beautiful building where I saw the Arctic Monkeys perform, in Berlin, that looks like a circus tent and I always just thought it was where the Circus Alekan had been set up. But maybe it’s in a completely different place?

Wim Wenders 1:07:09

You’re almost right. Do you remember where the little food stand is, where Peter Falk meets Damiel, and he says, “I can't see you, but I know you're there”? This is where the circus—this cement circus—is standing now. It's across from the Anhalter Bahnhof that Peter Falk is sort of thinking about, as he crosses the field, and as these people walk by, saying, “Hey, this couldn't possibly be Columbo.” This is where the tent is now.

Haden Guest 1:07:45

Let's do that question in the back there, to the left. And then we'll come up to you.

Audience 1:07:51

Thanks so much. You talked a little bit about how you developed the question, or the theme, of how angels experienced the world, in terms of what the camera was doing. I'm curious if you could talk more about how you worked that out. For example, we see scenes where, of course, when they walk through the library, they hear people's thoughts. But also moments that are more subtle. When, you know, when they'll sort of cover their ears and seem to focus on some particular sound. How did you work out this question of how angels sense, whether they need a notebook to write down and so on?

Wim Wenders 1:08:30

I figured they had a pretty good memory. But then, as we had this conversation between the two of them in this convertible, for some reason, I figured Otto—Casiel—would have a notebook. And he’s pulling this thing out, as if he had written down notes. I guess their memory must be extraordinary. And they do memorize things from before even men were there; people were there. They have quite an acute memory of events that happened there. So I think they must have a flawless memory. But I always had it in my head, from the beginning, that they wouldn't have any sensual experiences. That they wouldn't have any taste. And so it was a big deal, I figured, if Damiel was having his first cup of coffee. And of course, it's stupid, and I just made it up. Who knows anyway, if they can see black and white or not.

[LAUGHTER]

Maybe they see more colors than any of us. But it was sort of a useful idea to create this other world and to make it believable that they could hear our thoughts. So they have this whole different, other sensorium to register things. And the film also played in Japan. And I remember I went to the Japanese opening. It was a big theater in the Ginza. And about a year and a half, almost two years later, I came back for another reason. I think I had another film or something. And the distributor said, “I gotta show you something, Wim.” And he took me to the theater and I said, “Oh, wait a minute.” It was in Japanese writing, but I recognized it. “The film is still playing!” “Yeah,” he said, “but that's not what I was going to show you.” And we went back to the back entrance and walked into the theater. And we were behind the screen and there was a little door, and he opened it. And I saw it was packed. I said, “Oh, wow.” Okay, it was Sunday morning, 11 o'clock. “It's packed,” I said. “That's not what I wanted to show you.”

[LAUGHTER]

“Look.” And I needed to get used to the darkness. And then I saw it. It was a big theater. It was only women. Only. I couldn't see a single man. And that was quite something. We closed the door and walk out. And I said, “What is this?” I said. A lot of people write about it and try to explain it. And the best explanation I'd heard so far is that Japanese women are not used to men listening to them.

[LAUGHTER]

And that they love the idea of the angels listening to people's thoughts. And they just come back and come back, because they can’t get enough of men listening to them. I thought that was a good thing I’d done, with these angels listening to people. I was actually quite proud of that idea. All of a sudden, two years later.

Haden Guest 1:12:06

There's a question right here in the front. If you’d just wait for the mic, otherwise people won't hear you in the back.

Audience 1:12:20

Can you speak about your editing process and how much of the film was devised after photography was finished? You know, there's the internal monologues. And I'm just curious how much of the film creation really happened after the filming was finished.

Wim Wenders 1:12:38

The film was pretty much, as I said, shot in chronological order. Except for Peter’s performance, because he was only with us for two weeks, we had to sort of condense it. And then, of course, given the nature of a lot of the scenes, they could be swapped around and some of the order was not quite so solid. So in some areas of the film we could try a lot, with the flow of things. But in others, it was quite solid. And from the moment on, that Damiel was a human being, that was quite linear anyway. But we were in a big rush because we were shooting still until January, or February even, in 1987. And especially our French co-producer wanted us to be ready for Cannes, so we had four months for the editing, which is quite insane. And I knew from the beginning, some of the editing ideas of the films are very inspired by the fact that I knew that this was going to be my first film in stereo. So I knew I had this additional tool. And like for the voices, for instance, or the music that was also this cacophony of voices, or the angels could listen to voices. It would not have been an idea that would have worked in a mono film. Paris, Texas was still in mono, but this was the first one, and sound, and the work on the sound, informed a lot of the editing. And in the end, there was not all that much we didn't use, because we didn't have all that much money. And we shot for five, almost six weeks, and that was it. And the film is relatively long. Two hours, almost two and a half hours. And Peter, my editor, and I, we had worked on all my movies until then together. There was not a single one that he hadn't edited. So we were like Siamese twins. He had already edited my first student film. Pretending he was an editor. He had never edited anything, but he was cocky and said, “I can do this.” And I believed him. And I only found out, years later, that he had never edited before. And we were really, we were very close to him. And Peter could edit on the Steenbeck. It was of course all flatbed and not electronic. He could edit so fast, like people today can maybe work on an Avid, he did it. He was the fastest gun alive. And we had two tables. And I was working on a second table. And he let me edit some of the scenes that he thought were not important. So. But, given the fact that it's kind of complex, if you look at it now, and we had four months, it is still a mystery to me.

Haden Guest 1:16:06

I think we have time for just one or two more questions. I'll take... right there at the back. Gentleman with his hands up, please.

Audience 1:16:21

Hello. My question is about the scene where the two angels are speaking about life before, or existence before humans. And there's a part where they speak about humans learning to say “oh,” or to shout. Like for speech. There's another line where it seems to imply that angels learned language by way of humans learning language. Yeah, I was wondering if that, if I'm accurate in that implication, and where the idea came from. Thank you.

Wim Wenders 1:16:58

I was amazed when I read that. Peter wrote that. And I thought it was only natural that angels didn't have language and waited for us to finally learn it. But they sort of assimilated. Anyway, it was something Peter had come up with, and I thought it was quite logic. I don't know, I liked the idea. I was afraid your question was going to be about Peter Falk. How a former Angel could have a grandmother.

[LAUGHTER]

Because, every now and then, that question came up.

Haden Guest 1:17:41

And the answer?

Wim Wenders 1:17:42

Well, I mean, already, Peter loved to improvise so much. Also, when we did his interior voices—because we needed his interior voice just like most of the other people. And I had written some stuff for him and he said, “Oh no, no. None of them. Just let me close my eyes. I'm going to give you a whole lot of shit and it's going to be much better than any of what you wrote.” And then he’d ramble on for half an hour, and then finally he stopped, and I said, “Okay, good. I have enough, Peter. But, what am I gonna do with your grandmother? You know, as a former angel, you can’t have one?” But it was the best stuff. So I just left her in.

[LAUGHTER]

It was so sweet, the stuff about his Polish grandmother. One last question? In the center there. Yeah. Thank you.

Audience 1:18:49

Hi, thank you. My question is something that I've been thinking of, from watching Paris, Texas and also from watching Wings of Desire tonight, is this suspension of the physical—of the body—the restriction of the body. Being able to touch another body or like in Paris, Texas, we see Travis, when at the beginning, you can imagine this character needing the water, however his looking for water is so clean. Even his passing out, it's like he just falls on the ground and it feels so clean. And also, there's this suspension where he is not able to touch her ever. Jane, right? And Wings of Desire. We're like, traveling with these characters. They can't touch, they can't feel. They can't feel the weight of another body. However, you build up this desire. And even in the moment when they finally meet, where we are like, throughout the whole movie, now I understand why, right? Because you got lost, liking it so much, you know, with having the angels move around and explore, that we almost, as an audience, feel like we're not going to get there. We're never going to get there, right? To the moment where we have these two characters encounter, right? And touch each other. If you can talk a little bit about the suspension of the physical, I call it.

Wim Wenders 1:20:36

It was a big relief, to see them embrace each other. And of course, all the moments that lead up to it, with Damiel wanting to know the name of the colors and he gets to have a first cup of coffee. And then the very physical thing that– The only thing you see them do together is when he's holding the rope and helping her. And that needs such incredible coordination, actually, in order to work... It's such a physical connection, this rope. And of course, they do embrace and I felt a little bit like you, because I like Peter’s monologue really very much, but I kept thinking, “Oh boy, doesn't Bruno finally... would rather kiss her?” Or vice versa? And then she still kept going, so... But then I think it feels even better, that she finally does put her arms around him and they kiss. And it all leads to that in the end, and then you understand why this man had given up so much for that. I can't speak for Travis, because he actually doesn't get to touch Jane. And that is heartbreaking, but that is, a little bit, the rule of the game for him.

So now you got me thinking about, if that has something to do with me.

[LAUGHTER]

Audience 1:22:27

That's what I wanted to get to. You.

Wim Wenders 1:22:34

I look at my wife.

[LAUGHTER]

We have to talk about this.

[LAUGHTER]

Thank you so much.

Haden Guest 1:22:46

Thank you so much, Wim Wenders. Thank you all. Tomorrow at 2pm in Sanders Theater, please join us for Wenders’ second Norton lecture.

[APPLAUSE]

©Harvard Film Archive

Part of film series

Screenings from this program

Paris, Texas

Wings of Desire

Notebook on Cities and Clothes

A Trick of the Light