Searching for a path between receiving his Bachelor and Master of Arts degrees from Harvard in the late Forties, Robert Gardner (1925 - 2014) began to embark upon his lifelong journey documenting the arts and rituals of cultures near and far. Briefly studying anthropology in a formal sense, he credited Ruth Benedict’s seminal ethnographic treatise Patterns of Culture (1934) as impelling him toward filming the exteriors of other cultures—beginning with the Kwakiutl of the Pacific Northwest—as a means of understanding the interiors of all of humanity.

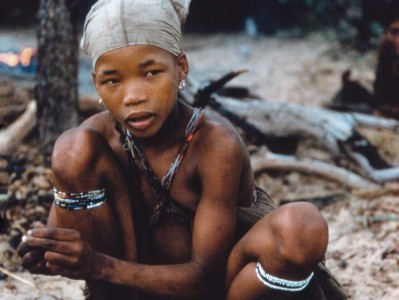

Returning to Harvard’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, he assisted graduate student John Marshall with The Hunters (1957)—an ethnographic classic featuring a tribe of hunter-gatherers in the Kalahari—footage which inaugurated the Film Study Center at the Peabody, the first program devoted to visual anthropology production on this continent. A few years later Gardner produced his first major film, Dead Birds (1964)—featuring the tribal Dani of New Guinea and their ritualized warfare. His unsentimental yet compassionate chronicle of a radically un-Western worldview became a cornerstone of visual anthropology and remains striking in its open-minded beauty and earnest artistry. In Gardner’s words, “The reason for going to the considerable trouble that finding and making this film required had its origin in an immodest hope that the film might persuade viewers that the people in it are not so different from themselves and that the central concerns of the film, human violence and mortality, are as important to everybody as to the people in the film.” With filmmakers like Marshall, Tim Asch and Jean Rouch, Robert Gardner was an integral voice within the next wave of visual documentarians who attempted to document other cultures with fresh, non-judgmental, non-patriarchal eyes—uniting an artist’s mastery of visual style with a humanistic philosophy.

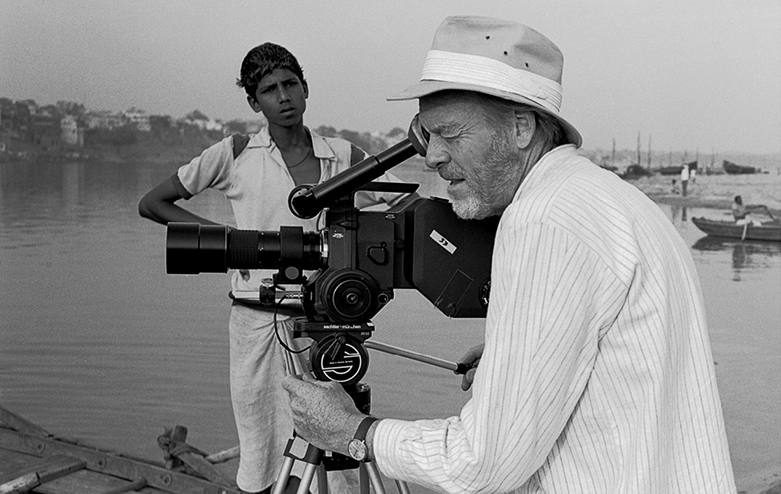

With his own particular ethos, he continued an adventurous, prolific life preserving images of singularly fascinating cultures and their art and religious practices—often those which called into question Western belief systems or strangely aligned with them despite an initial apparent disparity. Taking him from the mountains of Colombia to the deserts of Ethiopia to the shores of the Ganges, he negotiated a fine balance between intellectual poetry and objective ethnography. Though anthropologists immediately claimed his vivid, mesmerizing accounts as belonging solely to their realm, Gardner embraced a more expansive view; he allowed his personal vision to existentially translate the “other” while maintaining an honest, authentic rendering of humanity. In works like Ika Hands, Rivers of Sand and Forest of Bliss, Gardner discovered remote—often isolated—cosmoses in all corners of the earth where humans traversed the sacred realms of sublime transcendence and devastating suffering through vastly different practices. Translated through a skilled artist’s eyes for the world to then interpret as they wished, the films bear the mysterious marks of his own meditative scrutiny of these alternate, yet very corporeal realities and the acknowledgment that by filming them he also altered them.

Gardner found the creation of art both a unifying and differentiating function of cultures—instigating spiritual transcendence, providing history and memory, grounding humans to their mortality and distracting them from it. Thus, he worked as tirelessly and creatively documenting these practices as he did supporting artists and cultural practices on his own soil in a myriad of ways.

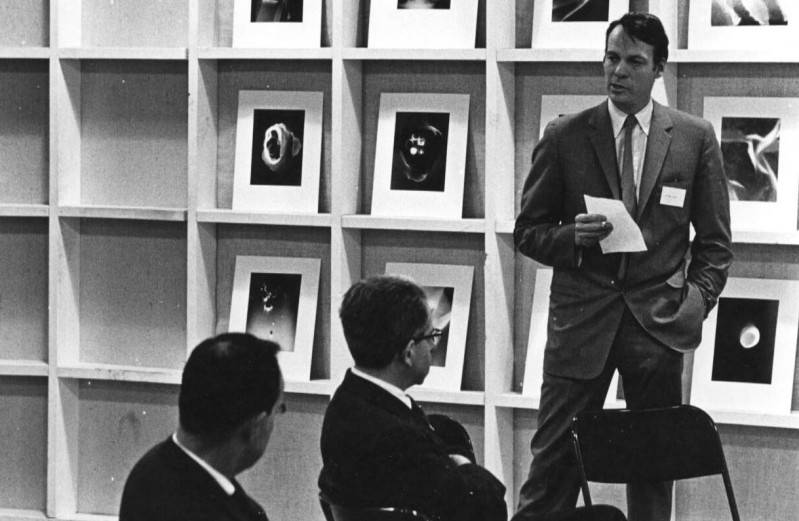

As the first director of the Film Study Center he oversaw its move to the Carpenter Center in 1964 and played a crucial role in Harvard’s burgeoning film program—initially titled the Department of Light and Communications—teaching film classes, founding the Harvard Film Archive with Vlada Petric and Stanley Cavell, and later directing the Carpenter Center for almost twenty years. Meanwhile, for the better part of the Seventies, he and fellow colleagues miraculously owned a broadcast television channel in Boston and Gardner hosted Screening Room, a series which exposed mainstream audiences—and many future filmmakers—to independent and avant garde films and techniques. Several years after retiring from Harvard, he established a “loose confederation” called Studio7Arts to promote his own work and support like-minded artists who “interpret the world through non-fiction media.”

A friend and collaborator to countless artists, poets and philosophers, Gardner surrounded himself with inspiration and talent. He made several cinematic tributes to his artist friends like Mark Tobey, Sean Scully and the filmmaker Miklos Jansco. He also wrote and published accounts of his travels and films, worked on unfinished fictional film scripts and left behind a trail of aborted projects. Most profoundly, his influence reverberates throughout contemporary documentary work today, from the work of filmmakers like Sharon Lockhart and Lucien Castaing-Taylor to the current students of Harvard’s own Sensory Ethnography Lab who have fully adopted an experimental approach to the ethnographic. – Brittany Gravely

About the Collection

Donated to Harvard in 2007, this collection contains 128 prints and outtakes from Robert Gardner's extensive oeuvre.

A finding aid for the paper portion of the Robert Gardner Collection can be found here.

Additional Resources

For more information about Robert Gardner and his work, visit his website.

Many of his films are distributed by Documentary Educational Resources.

Robert Gardner's obituary in the New York Times