Eyes Upside Down, An Illustrated Lecture by P. Adams Sitney, with introduction by Haden Guest.

Transcript

0:00 HADEN GUEST

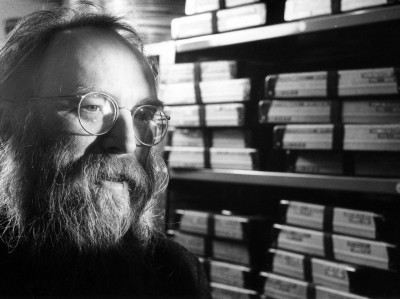

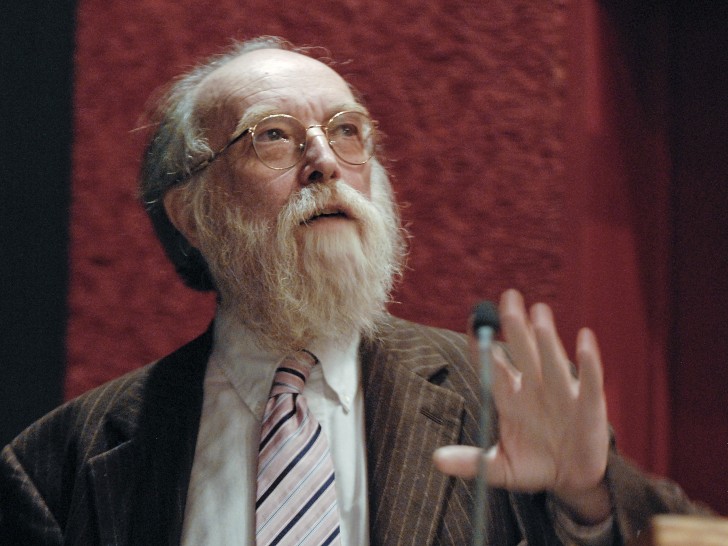

[INAUDIBLE] ... Film Archive. My name is Haden Guest, and I’m the HFA Director. And it is my enormous privilege and sincere pleasure to welcome P. Adams Sitney to the HFA for an illustrated lecture drawn from his latest book Eyes Upside Down. Illustrated meaning that it's a lecture that will include various films which will be shown. Eyes Upside Down is P. Adams’ latest book and we have a limited number of copies available for sale at the box office. Now, P. Adams Sitney is a name known to many of us. He is one of the world's foremost authorities on American experimental cinema and one of the most important film historians of his generation. P. Adams Sitney has been writing on film for over 40 years. He began precociously young, editing a remarkable film journal Filmwise when he was a mere teenager. He's never looked back or slowed down. Throughout his long and prolific career, P. Adams has consistently resisted academic fads in the more fashionable critical paradigms to instead forge a path that is entirely his own. A path whose most visible marker remains his magnum opus and most influential work, Visionary Film, from 1974. Marrying an ambitiously encyclopedic survey of experimental cinema with meticulous close readings of individual film text, Visionary Film simultaneously defined a new field of study and offered its primary text. The recent emergence of avant garde cinema as a substantive field within Film Studies owes a huge debt to P. Adams’ visionary scholarship. Responsible for coining the term structuralist cinema to describe one of the most significant bodies of American experimental cinema that emerged in the mid 60s, P. Adams’ critical writing itself has remained fascinated with the deeper structures and patterns within individual films and across filmmakers’ oeuvres. P. Adams’ writing on film has defined an important and influential mode of historic poetics that creates deeply insightful aesthetic categories for identifying and understanding the different threads interwoven throughout the history of American experimental cinema. Equally versed in literature and poetry as cinema, Sitney has pursued a parallel career as a literary scholar, writing his dissertation at Yale under the tutelage of Paul de Mann, Maurice Blanchot, and Charles Olson, writers who figure prominently in his Modernist Montage: The Obscurity of Vision in Cinema and Literature from 1990. And Sitney has also written a fabulous study of post-war Italian cinema, Vital Crises in Italian Cinema: Iconography, Stylistics, Politics from 1995, and I understand he's working on a new expanded edition of that important book, a book which I think counts as one of his very finest works. P. Adams’ literary training directly informs his latest work, the work that he will be speaking from today, Eyes Upside Down: Visionary Filmmakers and the Heritage of Emerson. And this is a work in which he examines the centrality and underappreciated influence of Emersonian poetics and the work of key American experimental filmmakers, and the way in which Emersonian ideas form the poetic and philosophical roots, the post-war American avant garde. I'm really pleased to welcome P. Adams here. Now just a technical note, the lecture will last approximately two hours and will be followed by a Q and A period, so please stay for that. And now please join me in welcoming P. Adams Sitney.

[APPLAUSE]

3:51 P. ADAMS SITNEY

Thank you very much Haden. I first met Haden when I was in California, as a guest of the Getty, and I’m extraordinarily happy to see that he has fit in so well here at Harvard and done such wonderful things here. I was last at this podium, I think it was about 30 years ago. It's been 30 years since I've spoken at Harvard. I've spent most of that time at a rival university far to the south, and it must have been close to the time that I wrote Visionary Film. One of the great problems I had in writing Visionary Film was with one filmmaker I deeply admired whom I was incapable of discussing, of writing about, and that was Marie Menken. I didn't have the intellectual conceptual tools to come to terms with her work. And so over the years, I always thought I wanted to do another book emphasizing not only what I had emphasized in Visionary Film, that is the romantic heritage and the romantic underpinnings of many of the major films of the American avant garde, but particularly the American inflection. And by American inflection, I often mean, or often insist, on the Emersonian tradition, and our aesthetic thought is so deeply permeated by the thought of Emerson that we hardly notice it. Certainly, I hardly noticed it, and resisted it 30 years ago. It is with a certain degree of intimidation that I launch into this talk in the presence of Stanley Cavell whom I deeply admire and who has taught us so much about the Emersonian tradition in American philosophy. Now, there's a particular passage I found in Emerson's Nature, which it has been under-discussed in the Emersonian literature, but at a certain point when I read it, suddenly it hit me that here was in nuce some of the scenario for many of the major achievements of the American avant garde cinema. I'm going to read you this passage and it may strike you as immediately as it did me. Emerson is talking about certain mechanical changes—that’s his phrase—certain mechanical changes that can alter our perspective. He says, “the least change in our point of view, gives the whole world a pictorial air. A man who seldom rides, needs only to get into a coach and traverse his own town to turn the street into a puppet show. The men, the women—talking, running, bartering, fighting—the earnest mechanic, the lounger, the beggar, the boys, the dogs are unrealized at once, or at least, wholly detached from all relation to the observer, and seen as a parent, not substantial beings. What new thoughts are suggested by seeing a face of country quite familiar and the rapid movement of the railroad car. Nay, the most wonted objects, make a very slight change in the point of vision, please us most. In a camera obscura, the butcher's cart and the figure of one of our own family amuse us. So the portrait of a well-known face gratifies us. Turn the eyes upside down by looking at the landscape through your legs, and how agreeable is the picture, though you have seen it anytime, these twenty years.” Turn the eyes upside down. Well, imagine turning the camera upside down, or pointing the camera out of the window of a moving vehicle in order to apprehend a new vision. Suddenly, the cinema of Menkin, of Brakhage, of Jonas Mekas, Michael Snow, Warren Sonbert, begins to take on a new life. I want to begin with an example. A film by Marie Menken made, shot, in 1958, and first shown in public in 1961, soundtrack and titles were put on in ’61, called Arabesque for Kenneth Anger, to bring us into our discussion. Can I have the first film, please?

[FILM SCREENING]

9:44 P. ADAMS SITNEY

Arabesque for Kenneth Anger. In the mid 1950s Kenneth Anger was living in Rome, and he visited the Gardens of Tivoli, the waterworks at Tivoli, and he had a notion that he would make a film there. But he was disappointed. He expected them to be bigger, so he searched for a midget. He wanted a very small person who could walk through the Gardens of Tivoli. He made a Baroque costume for this person and very carefully filmed someone moving, this figure moving through the Gardens of Tivoli. In the end, this figure, this woman merges into a fountain. Her flowered headdress takes the shape of the very carefully composed and filmed and edited by Anger to the rhythms of Vivaldi's Seasons. And then having edited the entire black-and-white film, he had it printed with a blue filter in deep blue and hand-painted in green [INAUDIBLE] It's called Eaux D’Artifice. Menken was a good friend of Anger, and he agreed to accompany her after the 1958 Brussels World Fair, Second International Competition of Experimental Films, to Spain where she wanted to film the Gravediggers of Guadix, a group of monks whom she had been, to whom she had been sending small contributions for many, many years. Menken herself was a working class, Lithuanian-American Catholic, and more or less a practicing Catholic of extremely liberal temperament in the very unliberal 50s of American Catholicism. Anger of course was a diabolist, a follower of Crowley. And so they went together to Spain and visited the Alhambra, and their Menken took out her camera and filmed around. Now this is a very characteristic American gesture. I cannot imagine any self-respecting, major European filmmaker who would go to a grand, tourist-attractive center of art and make a film of what he or she sees there. It would be a matter of both too much respect and an overwhelming intimidation. But just as Anger felt free to make Tivoli the theatrical backdrop for his Eaux D’Artifice, or that very same year, Anger, Menken, and Brakhage together went to the Père Lachaise Cemetery following that same festival and Brakhage shot in Père Lachaise his film that became The Dead. Here, Menken feels completely liberated and shoots a tourist film—a home movie as it were—of the Alhambra. When she showed this film for the first time in 1961, she stood before the audience of the Charles Theater at midnight and said, “Do you see those birds at the beginning? Well, that dove, that's me.” Now, a practicing Roman Catholic such as Menken, would, of course, be aware that the dove is the symbol, the icon of the Holy Ghost, the Holy Spirit, and in a certain ironic sense, this is a film of the descent of the Holy Spirit into the Alhambra. In a sense, from the point of view of the bird, the religiously inflected bird, the entire Alhambra is one large and gorgeous bird bath to which it descends. And so Menken herself enters as an outsider figure, recording the Alhambra as the backdrop to her own movements. She was anything but a midget, six foot two or three, a very large woman who believed in holding the camera in such a way to inscribe her somatic presence towards, in front of, anything that she films. To see a Marie Menken film is, in a sense, to see Marie Menken unseen in a particular location, in a particular landscape. As she moves around the Alhambra, sometimes, an object will halt her and hold her attention for a moment, but never so much that we don't feel at least the nervous vibration of her hands as she's trying to hold still, but more often, she'll freely move her camera, transforming the depths of space into a kind of whirling motion, often suggesting that same avian metaphor, as the portals of light turn like birds or the tiles themselves switch. She created a kind of cinema that a number of younger filmmakers immediately saw as a potential vocabulary, as a ground for their own syntax. And the filmmaker who took the most from Menken was the young Stan Brakhage who—when he arrived in New York and looked up Marie Menken and Maya Deren, actually moved into Maya Deren’s apartment for a while because he had nowhere else to stay—saw Menken’s films, and his style was really transformed. He'd begun to make films in the own oneiric style of Deren herself with touches of Italian neorealism, and suddenly, he began to seize the camera in his own hands. And in fact, it was this encounter with Menken that was the liberating force in Brakhage’s first distinctive and masterful style that led in 1958 to his film Anticipation of the Night. Also, there is a fundamental recognition. In a sense, Menken is not only saying in a film such as Arabesque for Kenneth Anger that, “I can do in a certain sense what Anger does so meticulously. If Anger has to go to so much trouble to get the blue tonality by printing his film, printing his black-and-white film through a color filter, I can just turn my lens down to a certain degree and everything is blue.” This is within a bluish world. If Anger’s film ends with this erupting orgasmic fountain, Marie Menken can find a similar fountain just in front of her. In a sense, though, what Marie Menken is suggesting is that this is not only a Christianization of the Arabic landscape, but much more importantly, a film about her own incarnation as an artist, her own self-baptism as a free-spirited American filmmaker.

Now I have packed this evening with so many films that I want to speak rapidly and quickly as we go from one to the other, leaving room for various questions and I'm going to jump from 1958 to the 1990s, to one of Brakhage’s great serial projects called Visions in Meditation. (The reason I was confused is it's inspired by Gertrude Stein's great poem Stanzas in Meditation.) Brakhage was rereading—as he had been most of his life—this long, extraordinarily difficult poem that Stein wrote at the same time that she was writing her most popular work, The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas. Brakhage’s life had a major disruption. The marriage of 30 years, which had been the subject of much of his cinema, had come to an end. He had just recently remarried, and married a woman who said that she would be happy to be married to him, but unlike his previous wife, she never wanted to be filmed. He would have to make the films without using her as image material, and if they had children, and they did have two—Brakhage had had five before—the children were not to be filmed either. So in Brakhage’s new, renewed life, there was new forms of restriction and enormous enthusiasm, both emotional, erotic enthusiasm, amorous enthusiasm, and as it were, a re-inheriting of the world for his cinema. So he launched upon a series of films, Visions in Meditation—four films, and we will see the first of them now. It is a silent film.

[FILM SCREENING]

20:38 P. ADAMS SITNEY

[INAUDIBLE] —position at the University of Colorado where he had been teaching. He was a distinguished professor, which meant a great deal to him not so much because of the honorific title but because he would get a full salary for teaching half time and able to work and continue his cinematic work more productively. And on that occasion, he was asked to give a public lecture to the faculty of the University of Colorado, and he gave a talk called Gertrude Stein and the Cinema. And I want to read you a little bit of that because it's particularly relevant to this film. Brakhage says, “I have made my Visions in Meditation in homage to Gertrude Stein's whole meditative oeuvre, epitomized by her Stanzas in Meditation. When this series opens with an image of a white building, whited out, it's not necessary to know the source of this photograph, that the structure represented and overexposed is the oldest church in Maine is not relevant information with respect to the film. These formal transformations of this once church now exists in a film that will realize itself through the life of shapes of white. What it referentially is, was, when photographed crucial to my composing of it, my f-stop take of it, the rhythms of my gradual overexposure and later editorial juxtaposition of it. The original cluster of shapes generated by this photographed church ought to cause, through shape shifts throughout, some sense of the sacred.” In the same essay, he speaks of how the metamorphic—metaphorical meaning intrinsic to the work could even inculcate the antithetical—capital antithetical—in as much as art, like Freud's unconscious, joins opposites as one, at once, in timeless fusion. Now, as we look at the film, we see a traveler moving through this frozen space. There is a subgenre of American avant-garde cinema, a kind of what classical rhetoric might call a periegeten, a representation of a work of travel. Another classical name for it is topographia. In fact, virtually all the films that you'll see in the next couple of weeks, in the retrospective of Warren Sonbert’s work, constitute periegeten or topographia as Sonbert endlessly traveled around the world, making film after film of his voyages, combining space. Brakhage uses this form throughout the entire Visions in Meditation. Here, he's in Canada, Maine, and New England states. Later, in part two, he's at Mesa Verde in New Mexico. In part three, he's at the Carlsboro Caverns and several places in Texas, and finally, in part four, makes a trip to Taos to pay homage to the house of D. H. Lawrence. So what we see through the film is not really the place to which he is going but the act of travel as Brakhage moves through these spaces.

Now, you might have recognized in the second sentence that I read to you from the Emersonian text, an echo of the work of Walt Whitman, a pre-echo. When Emerson writes, “the men, the women talking, running, bartering, fighting, the earnest mechanic, the lounger, the beggar, the boys, the dogs unrealised at once,” that catalog is distinctively Whitmanian. Not because Emerson took it from Whitman. Quite the other way around. Whitman has said that it was reading Emerson that brought him to a boil and that characteristic catalog of sites, the sense of moving through space, by the naming of the parts of places is the Whitmanian heritage that Brakhage inherits along with his view of Emerson. What we see in Brakhage’s films then is a meditation on a frozen landscape in the sense of a man moving through it and seeing things that he can barely know, which the limitations of his knowledge are at stake. For instance, we have very few human presences in this film. The most sustained human presences are the photographs, apparently of people long dead early in the film. Later on, we see a couple of people walking with a dog along the beach. At another crucial point near the end of the film, a young boy playing in the yard. Part of the poignancy of the film is that we do not know who these people are, we do not know the source or the story of these photographs, and presumably, Brakhage doesn't know them either. This is a landscape through which he is moving, a landscape that touches at once upon the sublime, classic American sublime with glimpses of Niagara in the midst, and the mundane, virtually any frozen place an automobile travels through. Brakhage’s entire effort in this film is to record the movement of his mind as he comes to terms with these places to see a sense of renewal emerging, and this will become clear and clearer in the subsequent parts of the film, which I don't have time to show you tonight, but we get two senses of that, one in what is a classic cinematic trope. We find it in Russian films like Podovkin’s Mother. The breakup of the ice, we find it in Griffith’s Way Down East as a harbinger of the coming of spring, and Brakhage gives us a strong glimpse of a dormant Ferris wheel, which we know will come into motion with the change of seasons, which is itself an echo of Brakhage’s early signature film, Anticipation of the Night. So Brakhage’s film is poised in what he calls the antithetical, and I hope you noticed a rhetorical strategy that Brakhage uses. He employs the figure of apophasis, that is, when he says, you don't have to know what this opening image is, and then goes on to tell you that, as if you could forget it once you heard it, that it is an image of the oldest church in Maine. Likewise, in the same lecture, he talks about a Stein text that describes—that emerges from the erotic intensity of her love for Alice B. Toklas. Again using apophasis to declare that one doesn't have to know any of that to appreciate the power and beauty of the words. Now Brakhage’s film is located then in an antithetical zone between the idea of the totally autonomous work of art and, at the other pole, the biographical dimension of referentiality. And part of the landscape that Brakhage negotiates late in his career is the movement between the two. And I take that to be one of the reasons that he invokes this sense of the family photograph and yet the unknown ancestor at that very beginning moment.

I want to move quickly then from Brakhage to a very different kind of filmmaker using the sense of the vehicular in a very different way, and that is Ernie Gehr with his very short film, Shift, which we will see next.

[FILM SCREENING]

31:23 P. ADAMS SITNEY

The filmmaker, Ernie Gehr, is such a private person that he borders on the secretive even when giving an interview and certainly makes his films to keep himself out of the film. In a certain sense, the level of the repression of the autobiographical in Gehr’s film is part of their strength, the degree to which other forms of selfhood emerge. This film is an almost perfect example of what I deduced to be the Emersonian principle of by certain mechanical changes, the equivalent of seeing the world upside down by putting one's head between one’s legs can be created to give a new cinematic vision. This film was made entirely with a Bolex camera, without optical printing, without any effects afterwards. In other words, Gehr filmed the scenes, sometimes he turned the film upside down in order to get it to go backwards, and at a certain point, he hand cranked the Bolex camera knowing that the frame would misregister and that he would have imagery jumping over the frame line. He edited the film to a common sound effects record of car noises. And yet, well, had we had enough time I would show an even more perfect example of this. Gehr made a masterpiece in the late 1990s called Side/Walk/Shuttle, filmed in San Francisco from the exterior glass elevator of a major hotel, where, surreptitiously, he would ride up and down, sometimes holding his camera upside down, capturing different angles of the moving landscape and orchestrating them into an utterly fantastic and wonderful film. What we see in this film is an expression of street life by someone who perceived it with great intensity. One summer Gehr found himself loft sitting for the dramatist Richard Foreman and his wife Kate Manheim while they were off doing a play in France. Gehr has a preternatural sensitivity to sound. He finds it very difficult to exist in many urban environments because of the sense of sound, and he discovered that on Wooster street in Soho, even though he was on the top floor of a large loft building, he was assaulted by the sounds of the street so much so that in order to master this barrage, he put his camera at the window and began to make a film of what he was hearing and now seeing. And the work is this beautiful poem of an homage to the very power and shape of the cinematic frame. Gehr brilliantly uses two and three white traffic marks on the street to establish strong diagonals through which the traffic moves and very often against which it moves. He has a large variety of vehicular possibilities, garbage trucks, buses, vans, bicycle, and as if a god-given gift in the middle of the film, Fox Piano Movers, in which music itself is moving through the center of his frame. The lento rhythm of the beginning of the film suddenly shifts, following the title of the film, at the point where the frame line begins to appear, and it's almost as though the traffic leaps itself over the frame line as though it crashes through the frame line of the film as we hear the sound of the car crash for that powerful back and forth, straight and upside down ending.

Although the title seems, to some extent, to be a witty pun on the name of the filmmaker, Ernie Gehr, G-E-H-R, has made a kind of gear shift in this film. There's also a way in which that pronoun that Gehr tries to avoid so much, the solitary I, the pronoun of the vowel which is the pronoun of the selfhood in so much of avant-garde cinema, nevertheless finds its way into his title wedged in between the call for silence—shhhhh—and the sound of the street—phffft. So shhhh I phffft is the nature of this little film.

I want to show you two films—but I'll speak between them—by Hollis Frampton. One called Apparatus Sum, a silent film, and then one called Gloria, a sound film, but I'll be talking in between. First, Apparatus Sum.

[FILM SCREENING]

38:07 P. ADAMS SITNEY

There has been both a kind of succession in the history of these filmmakers and, of course, degrees of overt and repressed rivalry. Maya Deren, one of the great founding figures of this tradition, was herself a theoretician as well as a filmmaker. And shortly after Maya Deren died prematurely of a cerebral hemorrhage in 1961, I believe, Stan Brakhage began to publish film theory, and shortly after Brakhage stopped writing theoretical texts, or temporarily stopped writing theoretical texts and announced he wasn't going to do it anymore, Hollis Frampton emerged as the primary theoretician filmmaker of his generation. And following the death of Frampton, there was rather a long hiatus, the period of the great academicization of artistic theory, the influence of certain French philosophers whose names might be known at Harvard. And a resurgence recently occurred with the publication of Abigail Child's theoretical volume, This is Called Moving, and Child actually teaches here in Boston at the Museum School.

Frampton had a fruitful and often close and sometimes antagonistic relationship with Brakhage. Brakhage had announced in the 1970s that he was going to make a long autobiographical film that would be 24 hours long when he finished it. So, Frampton announced that he would make a film that would be 25 hours long and that would be shown over 365 days with special parts of the film for the equinoxes and for Frampton’s own birthday, and that this film was to be called Magellan. And one of the very first elements he shot early on in Magellan is this film which he calls, Apparatus Sum. Latin title, which means, among other things, "most evidently, I am thoroughly prepared." Apparatus, thoroughly prepared. Sum, I am. And it is a shocking film. Out of the color field and emphasis on red and the evocation of water, suddenly there emerges what looks like a pre-Colombian mask or face and as the camera slowly pans down, we are shocked to see that this is not a mask of any sort, but the actual head of a man severed at the throat. It turns out to be a medical school corpse as Frampton’s camera slowly circumnavigates the body in superimposition. Now, it's no coincidence that Brakhage had previously made a film of an autopsy room called The Act of Seeing With One's Own Eyes. In fact, the autopsy would be literally rendered as with one's own eyes. Brakhage had made the film because Sally Dixon—who ran the film program at the Carnegie Institute—was very influential in Pittsburgh and could get filmmakers access to things they couldn't have normal access to. So Brakhage got into a police car and rode around with the police and made a film, Eyes. He got to see open heart surgery and made a film called Deus Ex, and the last of that series was when he asked to go into the autopsy room and filmed a series of autopsies. Frampton then went to Sally Dixon and said, "Can you get me into the medical school because I want to film body parts for my Magellan?"

Now, this film, Apparatus Sum, has its own aggressive theoretical connotation. Frampton would have read, in Film Culture magazine, the writings of Dziga Vertov when they were first published in English in a translation by the photographer, Val Telberk. In that issue of Film Culture, Vertov says the following: “I am eye,” that is, the pronoun I, organ of sight, “I am eye. I have created a man more perfect than Adam. I have created thousands of different people in accordance with previously prepared plans and charts. I, a machine, am showing you the world the likes of which only I can see. This is I, apparatus maneuvering in the chaos of movements, recording one movement after another in the most complex combinations.” Now what Vertov means when he says that he has created a man more perfect than Adam is that he has filmed a detail, a part for the whole, a synecdoche of one person's feet running, and another person's arms throwing, another face smiling, and through montage, he can create the thoroughly synthetic image of a totally perfect man. This was, of course, a considerable theoretical insight in the early 1920s when Vertov wrote this polemical text. It is a coincidence of Val Telberk’s translation of the Russian that Vertov says, "I, a machine," and in the next paragraph says, "this is I, apparatus." Frampton, I'm certain, read this text and ironically refers to Vertov’s theory, literalizing the synecdoche. I have taken the head of a man, as if severing the head to give us the full shock and weight of what this theoretical metaphor implies, and moved his camera around it, dramatized it, setting it up first, by giving us the abstract color patterns, the long concentration on red in order to maximalize the effect of the camera roving over the dead corpse. Seeing in the corpse a new found beauty as Emerson himself had once said of corpses.

Now one of the major achievements of Frampton, in his large scale argument with Brakhage’s aesthetics, was to reject Brakhage’s emphasis on the obliteration of language. Brakhage, following the principles that many Abstract Expressionists were fond of, believed that words keep us from seeing, that it is part of the meditation of the visual artist to overcome the name for everything and to see it afresh, so his cinema was not only silent, but aspired to a kind of transcendent of or at least disengagement with the naming facility. One of the things that Frampton did that inspired so many filmmakers of the next generation, people such as Abigail Child, was to put words into his film, to actually engage with the visible word, and I'm going to show you now the dedication part of Magellan. Frampton never lived to complete the work of Magellan, but he did create this very brief dedication.

[FILM SCREENING]

48:16 P. ADAMS SITNEY

In a somewhat different register, the use of unusual visual perspectives and vehicular movement, Emerson spoke of common ordinary words as fossil poetry. And a number of filmmakers, beginning in the late 1960s, began to find in the cinema of the period before the First World War, fossil poetry. The first filmmaker to make extensive use of such an early film was Ken Jacobs, who remade a film called Tom, Tom, the Piper’s Son by re-photographing it in loving detail. And Ernie Gehr took a film of a cable car ride in San Francisco at the turn of the century and extended it into Eureka. Many filmmakers found an enormous treasure trove in the paper print collection of the Library of Congress. In the early days of copyright, it was required of every film producer who wanted a copyright to produce one paper print of every single frame of any film they wanted copyrighted. So if you had a film, a five-minute film, you wanted copyrighted, in 1902 or 5, you had to send reams and reams of photographs off to the Library of Congress. Eventually the Library of Congress realized that this was a clumsy way to do it, and they stopped that mode, but they still had these paper copies, long after many of the films themselves had disappeared, had been scraped down for silver content or had eroded, and the National Endowment for the Humanities in the late 1960s instituted a brilliant project. They would re-animate these films. They would take one frame of film for every paper print, and reconstitute a visually limited if not defective, but nevertheless, a version of all of those lost films copyrighted in the first years of American cinema, and they would be the property of the American people. That is, anyone could write to the Library of Congress and pay four, five, ten dollars depending on how long the film was and get any of these films. Plus, they published a big catalogue of this. This became a treasure trove of fossil poetry for any number of filmmakers, including Stan Brakhage who ordered some of these films and, in fact, used several of them in his second part of Visions in Meditation, the Mesa Verde film. Frampton collected a great many of them. In fact, he said, he found himself like Lévi-Strauss, going to Brazil himself, going to the wilds of Washington DC to look for the so-called lost, primitive cinema, and two of the films that he found there from 1903 struck particular chords for him because these were films about—one was called Murphy's Wake and one was called The Funeral in Hell's Kitchen—and they were films about funerals in which a corpse was revived because the alcohol which was consumed at the funeral fell on the corpse and brought it back to life.

Frampton, of course, was the most literate of the great filmmakers and was a passionate follower and reader of one writer above others, James Joyce, and of course, he knew that Joyce had taken a popular Irish ballad, The Ballad of Tim Finnegan, about a worker who falls off a ladder and dies, and at his funeral, there is so much liquor passing back and forth, that liquor falls on the corpse and Tim Finnegan rises again, rejuvenated by the alcohol. In a certain sense, Frampton recognized that what the National Endowment for the Humanities had done was itself an act of resurrection. They had issued the veni foras Lazare to so many of these films that they rose from the death of paper prints, and he took two of them to frame this work and give them new meaning. Furthermore, he must have noted, although I don't know that this was necessarily the case, that the murderer in the second of those two films looked uncannily like Frampton himself when we see him in close up. So what Frampton gives us, then, is an homage to the early cinema and a look forward to the cinema of the 21st century. A cinema that would take advantage of the new tool, the computer. So we are back in the period of the green screen and the slow moving computer phase as the catalog of remembered attributes about his grandmother appear on the screen. And here we see Frampton’s passionate concern for different systems of taxonomy. An alphabetical system describing how vividly he remembers these facts and his concept of their veracity, as well as many numerical and taxonometric systems within the film itself.

Now, in this dedication to his grandmother there is a fascinating and deeply personal ellipses. Frampton was not like Gehr in that he did, on occasion, speak of the things that most moved him and most troubled him of a personal nature. And one of the areas that caused him great anguish was the psychological situation of his mother, who was psychotic and institutionalized. In fact, Frampton’s formation and Frampton's influence in American art was to some extent a function of this psychosis because he was unable to bear the situation at home, and he applied and won a scholarship to Phillips Academy at Andover to be away from his mother, where he found himself rooming with a guy who didn't want to go to college but wanting to make sculpture, Carl Andre, and across the hall was Frank Stella, and the composer Frederic Rzewski was in that class as well as the filmmakers, Les Blank and Standish Lawder. It was an extraordinary conjunction of American artists all at Andover for a period of two years, of whom the know-it-all, avant-garde figure in touch with everything in modern art was Hollis Frampton. Frampton was—in a sense—the leader of that group. Following Andover, he was to go to Harvard. Harvard's loss comes about from the fact that the headmaster of Andover said this man did not complete his history requirement and said that his admission to Harvard should be rescinded. It is not to Harvard's credit that they listened to the headmaster of Andover. Frampton studied Greek for a little at Case Western and then went to what was colloquially called Ezraversity. That is, he moved to Washington DC to sit at the foot of Ezra Pound in St. Elizabeth’s Hospital. And without a college degree or even a high school degree since they wouldn't give him his diploma at Andover, moved to New York, where he lived with Andre, and became first a photographer and then a filmmaker. He was very proud of the fact that through the good offices of Gerald O’Grady, he became a full professor at the State University of New York, in Buffalo, without so much as a high school degree.

But what we see in this biography of the grandmother is, of course, a picture of the childhood of Frampton himself, of his identification with Caliban, his learning to read, his particular love of his grandmother and the radical absence of any allusion to his mother. His identification through her with the world of Joyce, through Irishness, and especially through that enigmatic last entry, how the last request of the grandmother was for a bushel basket full of empty quart bottles. "Full of empty" is the kind of oxymoron that would appeal to Frampton, but it seems enigmatic until seeing the rest of the film. We might deduce that this was a woman planning for her own funeral, planning for any number of pints of homemade alcohol to be prepared on this occasion, and there was a way in which the combination of words and of music and of the fossil poetry of old American cinema brought Frampton’s life and his work into context, into a touching relationship contact with the encyclopedic final work of James Joyce, Finnegans Wake.

And for final works, I will turn now to a film by Su Friedrich, a filmmaker who learned a great deal—was inspired by Frampton’s use of language—turned it in another direction. Stan Brakhage had often filmed the dream work inspired by his own dreams and sometimes would hand scratch his titles onto film, and in the few times that he ever used words—well, almost, with one or two exceptions—used words in his later work, he would hand etch them into the films so it would be a kind of moving imagery on the screen. Here, Su Friedrich—in the first film that attracted attention to herself as a filmmaker, in a sense, her self incarnation as a filmmaker, Gently Down the Stream—combines Frampton’s sense of language with some of Brakhage’s technique in an utterly unique mode, all her own.

[FILM SCREENING]

1:00:55 P. ADAMS SITNEY

I'll just say a few words about this film, since it's been such a very long evening, give you an opportunity to escape while I take questions from anyone who wishes to remain. One of the most remarkable things that the generation of Su Friedrich taught us who have been following the American avant-garde film for 20 or 30 years, was the fact that although, since the 1940s, such cinema had been almost unique internationally in its acknowledgement of homoerotic sexuality, the work of people such as Kenneth Anger and Willard Maas and any number of other filmmakers, the lesbian sexuality had been virtually ignored, and the filmmakers of the late 1970s, throughout the 1970s, the 1980s, the entire area of cinema was radically rejuvenated by the entrance of a generation of women filmmakers, often extremely critical of what they consider the patriarchal tradition of the major American avant-garde filmmakers and bringing a whole set of new perspectives to this domain. What this film evokes, then, is a relationship between sexuality and artistic incarnation. And, well, from the very beginning a kind of humorous representation of the traditional church, associated with the mother, and the modern equivalent of the church, the exercise gymnasium, played back and forth, the sense of vehicular movement set in the motion of the whale watch as the film progresses towards those glimpse of the porpoises. And we should remember that just as the leopard which appears in one of these dreams is the iconic animal of Dionysius, the porpoise and the whale are similar to Apollo. This is a film that touches upon the mythic realms of Apollo and Dionysius, the gods of tragedy and of poetic song. It is a film in which the filmmaker is—as she says in the film—giving birth to herself but giving birth to herself as an artist. She's a kind of Pygmalion figure in her dream who blows up an image of her own creation and then makes love to it. These are dreams of great creative power, fused with anxiety and guilt. Twice in the film she asks the question, which is the original, as if questioning her own originality, and as the film moves towards its conclusion, a kind of Oedipal rage inherent from the beginning becomes more and more apparent. When she says that five women sing, in acapella, funny harmony, they spell the word truth. In German, I spell, b- l- i- n -d- n- e- s- s. A man says their song is a very clever pun. I say, I can't agree, I don't know German. So, Friedrich's mother was German, her mother’s Mutter Sproch then was German, and it is significant, that in the fluttering language of utter, mutter, flutter appears the term Mutter and that the relationship between truth and blindness is the story of Oedipus as well as the prophet Tiresias. To a certain important extent, this cinema dwells upon such moments of productive antitheses and ambiguity. And at that point, I’ll wish you a good night.

[APPLAUSE]

Please feel free to leave either now or any subsequent point. If people are asking questions, I certainly don't mind that people have lives to lead and places to go. Are there any questions I can possibly entertain while people are stampeding for the doors?

[LAUGHTER]

If there's a hand, yes, sir.

01:06:44 AUDIENCE

[INAUDIBLE]

1:07:07 P. ADAMS SITNEY

Oh, I'm an old fart. I don't like computers. I don't like digital. You know, I like chemical imagery. But how I feel about it doesn't matter. It's insignificant. I mean, Frampton was fascinated by the creative possibilities of the computer. He wanted to move in that direction very much. And of course for my students, the computer is a totally natural instrument. There was already one there when they learned to crawl. The one problem I have—I teach at Princeton—and I'm unusual in that I don't allow computers into the classroom, and students are sort of saying, "What's the matter with this guy? He doesn't want..." Part of the reason is I audit a lot of classes in Princeton and I always sit in the back of the room, so I get to see people doing their email, their pornography, reading the New York Times, and all those other things that seem also quite natural to my students. They're, you know, "multitasking" is the optimistic way in which they put it—A-D-D is another way of describing it—but again, you know, you're talking to an old man who doesn't like anything to change. I mean, I haven't been at Harvard in 30 years, and I was shocked to discover there's no more Elsie’s. The young people won't even know what that means. [LAUGHTER] You know, that?—No Cronin’s, no Elsie’s—Do they still have school at Harvard? [LAUGHTER]

1:08:54 AUDIENCE

How does it change the primacy of the sort of visionary, romantic nature of relating to an image? [INAUDIBLE]

1:09:12 P. ADAMS SITNEY

You know, that's the famous—you've heard it a million times always quoted out of context, so I'll do the same. Karl Marx talking about Hegel: "Everything happens twice," Hegel says. He forgot to mention, "the first time is tragedy, the second time is farce." I mean, that a screensaver is completely different from an original work. I'm enough of a mystic to believe that when something happens the first time, it carries with it such an energetic charge that that charge remains, that when it is repeated and turned into some kind of brand, all that charge has dissipated. It's gone. So I mean, there are many people who—the only thing I do is reveal my age and my sclerosis when I go into this particular topic. It's a source of inspiration to many, many filmmakers, and one of the interesting things about Frampton was he was way ahead of the game. He was out there moving towards video related imagery long before others. In fact, he once told me that he wanted to have a program that– Now the problem with Frampton, Frampton was a bit of a fabulist. You can't always believe everything he ever said. He told me the following thing. He said he wanted a program that would scan photographs for gradual darkness, so that he could take a thousand photographs of all sorts of different images and put them in a row so that they become gradually darker, but no one would recognize, since they were so varied in their elements, that they were becoming darker and darker. But he was told that the CIA had this program as a coding device and it couldn’t be real. That may be, but this is the sort of thing he was talking of and thinking about in 1968 when I first met him. And all along he was concerned with further and further development of computer technology because he was interested in fantastic systems of sorting and organization. And in fact, in his great serial film, Hapax Legomena, he filmed a section with a primitive video camera. He visited the campus of SUNY Binghamton and they had, you know, a Portapak. It was a rare thing in those times, and Frampton borrowed the Portapak and walked around the campus, holding his hand in front of the Portapak, and made a film that he then had transferred to film to get that particular texture.

1:11:57 AUDIENCE

[INAUDIBLE]

1:12:00 P. ADAMS SITNEY

Endless repetition? No, but enough repetition to test you. Endless, not.

Are there other questions? [INAUDIBLE] Or does my scree on computers alienate everyone in the room?

1:12:20 DAVID PENDLETON

Also, if I could ask if we could just wait for that audience mic to get to you so we get—

1:12:25 P. ADAMS SITNEY

Oh, sure. Now it's working. Okay. Here we come with the audience mic.

1:12:30 AUDIENCE

Excuse me. Oh. I just wanted to know, what year did you discover that you could look at a landscape upside down or was it you who discovered that?

1:12:41 P. ADAMS SITNEY

Well, Emerson talks about this in 1835 as a major aesthetic mode. I'm pretty old, but I wasn't in touch with him at the time. [LAUGHTER] No, I had seen filmmakers do this in various ways. There's virtually anything you'll find in any of these films, if isolated, appears in some other film, once or twice. What is important for Marie Menken is the recognition that you can generate an entire film by walking around a place. That one simple structure. In his first book of film theory, Stanley Cavell speaks of automatisms in painting—a kind of stylistic mode that with great confidence generates a new painting. He's talking particularly of Pollock at that time, and there were these filmmakers such as Menken and Gehr and Brakhage who, in a sense, developed cinematic automatisms. They would discover a mode that could, for a certain number of years or a certain aspect of their career, generate a number of convincing films. One of those important modes was the flipping the camera upside down sideways, or what I called the somatic camera. By making the camera equivalent to the motions of her large body, Menken found an automatism to generate many of her best films. And that was beginning around 1942, when she was at– Noguchi had asked her to sweep up his studiowhile he was away, and keep a look on it, and so she walked around his sculpture and made her fabulous film, Visual Variations on Noguchi. Menken was the personal secretary of Hilla Rebay, the director of the Solomon Guggenheim Museum of Non-Objective Art, so in the 30s and 40s, she was in touch with any number of artists. She was the person people went to if they need—a young painter would come to—if they needed a job, so she hired the young Jackson Pollock to move the paintings around in the basement, and the young Robert De Niro, the father of the artist, to do that sort of thing. She was in touch with the young Noguchi at that point.

Yes—microphone is coming to you.

1:15:38 AUDIENCE

I wonder if you could talk about what you make of this particularly Emersonian avant-garde in America that you lay out here in relation to other avant-garde movements internationally? During the postwar period, or even the pre-war period in which there was a movement away from an autonomousness in art, not toward autobiography, but toward a more direct engagement with the social.

1:16:19 P. ADAMS SITNEY

Well, you know, it's interesting. It turns out, when you give it 20 years, that it's very difficult to distinguish direct engagement with the social world from autobiography [INAUDIBLE] since no artist, perhaps no person—no artist radically changes the social world in his or her lifetime. These are highly stylized modes of engagement often coming out of deeply personal and idiosyncratic perspectives. So, this has more to do with the polemical language of the avant-garde than the actual production. One place where this occurs is in the film avant-garde of Great Britain, where a filmmaker such as Peter Gidel would claim that it is socially improper to have a human being in a film. It is too delimiting that you have to recognize the human being as male or female, etc. You end up with a kind of highly abstract declaration of the fundamental components of the screen. And this is work which is deeply influenced by seeing works of Michael Snow and Stan Brakhage at certain points, so it's hard to distinguish that particular element. I would say that one thing I would look forward to—and I haven't seen much of it—would be an Italian writing about the roots of Italian culture and Italian thought in Italian avant-garde painting and art, or German. But it doesn't have to be someone of that kind, but someone who thoroughly knows the native traditions. I'm not at all certain that native traditions can be seen as distinctively as I now think I see this American tradition, but I suspect there's a lot to it. I suspect there are aspects of German postwar painting and film that are so deeply tied with not simply a reaction to the horror of Germany in the 30s but to long Germanic traditions that it could be seen by a sensitive critic, but I'm not the person who has that ability. I did devote some years of my life to studying Italian cinema in the context of Italian history, and I think there are intense relationships between even parliamentary activity in Italy as well as long standing cultural formation. For instance, the way in which Dante permeates Italian education in the work of people such as De Sica and Fellini and Pasolini. But I wouldn't be prepared to offer that kind of authority about Japan or Portugal, and so on. I wish I could. Am I answering your question or am I evading it or both? Yeah, I thought so. Thank you, that’s...

Oh, microphone coming. Okay. Ah. Oh, they're coming from all directions.

1:20:42 AUDIENCE

Okay. One of the things that the Emerson passage you read suggests is that the person who needs to see the world differently risks being completely ridiculous. That is, if I walk around [with] my head between my knees, somebody’s gonna ask me if something's wrong. And I was wondering if that— [LAUGHTER]

1:20:58 P. ADAMS SITNEY

I don't think Emerson was suggesting it as a permanent mode of ambulation. [LAUGHTER]

1:21:05 AUDIENCE

No, but—

1:21:06 P. ADAMS SITNEY

Yeah, you don't want to be caught doing it in front of your department chairman. Yes.

1:21:11 AUDIENCE

That's right. But I guess what I wanted to ask was that—how that willingness to risk ridicule permeates the American avant-garde in a way that maybe it doesn't in certain other traditions or if you don't want to go that way?

1:21:26 P. ADAMS SITNEY

Oh, I think artists are up for ridicule internationally, especially innovative artists. But there's a wonderful passage—I wish I had my book Modernist Montage—because there's a wonderful passage in Stein, and I can't quote it exactly, which uses those very terms about ignoring the ridicule. And, in fact, I wrote about it in relationship—this passage in Stein—to Emerson's essay Self-Reliance because there are actual verbal echoes there, that there is a long standing American—and to be American is almost for me to say Emersonian—tradition of eccentric self-reliance, and this is a tradition that the artists embrace wholeheartedly.

One key figure in this would be John Cage. Cage has always faced—in fact, relished—the idea of being seen as ridiculous in this mode. And there's a certain point in which Cage tells the story of walking with the artist Mark Tobey in, I think, Seattle, and they’re going to lunch but Tobey takes a very long time because he makes Cage walk looking at the sidewalk, staring at the sidewalk and appreciating the wonderful composition of the cracks in the sidewalk as they walk— [INAUDIBLE] Cage considers it one of the great aesthetic lessons. I don't think Marie Menken knew that story when she made her film, Sidewalks, in which Menken walks with her camera, actually, [INAUDIBLE] she gets someone else to do it, but walks with the camera, following the cracks [INAUDIBLE] to generate [INAUDIBLE] the entire film. Yes, it is ridiculous.

Interestingly, in 1963 and 4, I was very young. I was 19. I took a collection of avant-garde films around Europe, and the place where the films and myself were most blatantly humiliated—I mean, really, a scarring experience of humiliation was the Cinémathèque Française, where Langlois made a special appearance to say how bad and ridiculous these films were and what a great man he was for showing them, nevertheless. [LAUGHTER] Ironically, there's no place in the world where the American avant-garde cinema is more deeply appreciated right now than in Paris, and in places like Beaubourg and the Cinémathèque Française. Now, I didn't enjoy being ridiculous, but I wasn't the filmmaker. The sense of the ridiculous comes with the territory, especially if you are using what—adapting Cavell’s language—I have called an automatism to generate a film. Is that enough of an answer? Maybe it’s too much of an answer. Any other questions? Oh, yes. Haden.

1:25:06 HADEN GUEST

Thank you, P. Adams. You know, you traced this Emersonian logic throughout these diverse filmmakers, and I'm wondering in what ways we might more specifically use this logic that you trace as a way of historicizing the different strands of let's say the different interpretations of Emerson? For instance, we see with this first cluster of filmmakers that you deal with this interest in the gestural and in the vehicular. And then, in this lecture, it seemed particularly pronounced, this interest in language that we see in the work of the later filmmakers. And so, I'm wondering, for instance, the move into the university of many of the American avant-garde—so many filmmakers, for instance, teaching within a university setting. I wonder how that informs, let's say for instance, the interest in language?

1:26:11 P. ADAMS SITNEY

There seem to be a couple of questions there, and they're not the same. The question of the history of Emersonian interpretation—

1:26:24 HADEN GUEST

Well, no, you trace brilliantly in the book... You look through the biographical and wonderful ways and seeing that relationship—interrelationships among the avant-garde, as one way of historicizing their mode of dealing—the Emersonian mode that you see within the films. But at the same time, I'm wondering if some sort of broader historical rubrics can be created from looking at these?

1:26:49 P. ADAMS SITNEY

I can give you a crude, and I mean crude synoptic story. I mean, you have these very early filmmakers in this tradition, in the ’40s and early ’50s, such as Marie Menken and Ian Hugo, seizing upon such notions when they are simply ridiculous and daring to make some films with enormous exhilaration and liberation—the sense that they’ve have come upon something. And Brakhage quickly capitalizing on that, systematizing it, and with a prolific explosion of films. And you have a generation of filmmakers, shortly after that, who see what Hugo and Menken, to some extent Brakhage, have done, such as Jonas Mekas, Hollis Frampton, Robert Beavers. Any number of filmmakers who begin in the 1960s, and they—almost all of them—were college dropouts or autodidacts. And they're making films in this line. Now, something changes then. Once they begin to teach in the 1970s, you get a whole new generation of people who have traditional educations. I mean, I mentioned Abigail Child, she went to Harvard. Su Friedrich’s father is on the Committee of Social Thought at Chicago. She went to Chicago and then went to Oberlin. And some of these people began to see films in college, but none of that generation could major in films or probably even get credit for what they saw. There's a much greater problem for a subsequent generation in which making such films becomes a college subject. I mean, I have students who now consider going to see Rashomon or Hitchcock, nevermind Brakhage, to be homework and therefore to be avoided as much as possible. [LAUGHTER] Or, you know, rather than have to go out and see a print shown on the screen of Vertigo, they can get a DVD and flip it on and off their computer while going back and forth to email, and see if they catch it [INAUDIBLE] So you have a completely different environment of visual culture. I think it's much, much harder to be a young filmmaker now because of the institutionalization. But nevertheless, they keep on emerging, they keep on showing up, and there's been a revival in the past decade—an extraordinary revival. One that astonished me—more and more young filmmakers emerging. I was just this summer, you know, when Markopoulos died, he left– He re-edited all of his films, and even threw away the originals. Re-edited them into an 80-hour long film that he didn't even didn't have any money to print, and wanted it to be shown only in one place in Greece. And it was insane. [LAUGHTER] No, you know, who cares? Well, Robert Beavers, who lived with him, worked very hard, and after a number of years, raised enough money to show about 15 hours of this, and people came from all over the world to see this on a mountaintop in Greece. One of the most fabulous experiences of my cinematic life. Four years later, another 15 hours. If I live to be, I don’t know, a-hundred-and-twenty, I'll probably get to see the whole film. But the fact that there were 200 people who came from all over the world to sit all night long on this mountaintop in Greece, and it's cold up there as the screen, winks, slowly for five hours at a time is an enormous sign of revival. In Paris, you can buy t-shirts on the street with Jonas Mekas’s face on them. [LAUGHTER] I mean, some things have happened! None of these guys can make a living, but nevertheless!

You know there are amazing things that have happened. I'm lucky myself. I now have an editor at Oxford University Press who's willing to publish a book that's 417 pages long on such an obscure topic. She doesn't think she’s going to make any money on it, but at least this will happen. So I have a degree of optimism, and I am enthralled by the way in which I see young people showing up at screenings. And of course the good thing about it is they have everything to discover. They've never seen a Maya Deren film. This is amazing stuff. They’ve never seen a Brakhage film. Turns out, they're 350 of them for the person to see. There's something to look forward to. And they don't mind seeing Brakhage on the Criterion DVDs. They've grown up with DVDs, but I also note that there's a new revival kind of cultic formation. You probably see it here at the Harvard Film Archive, in which young people are beginning to talk about good 35 millimeter archival prints and tell each other when there's a good [INAUDIBLE] the Museum of Modern Art had an 8 and super-8 millimeter avant-garde [INAUDIBLE] about two years ago, three years ago. Last thing, about 30 or 40 screenings upstairs in the private screening room, and it was packed. Every single time, there were people wanting to see original gauge 8 and super-8 millimeter films. So there's something. I know I haven't answered your question, and I've talked much too long. So I think probably before everyone falls asleep or before everyone wakes up, we should probably call it an evening. [INAUDIBLE]

[APPLAUSE]

©Harvard Film Archive

Related film series

Explore more conversations

Leos Carax

John Gianvito & Soon-Mi Yoo

Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige