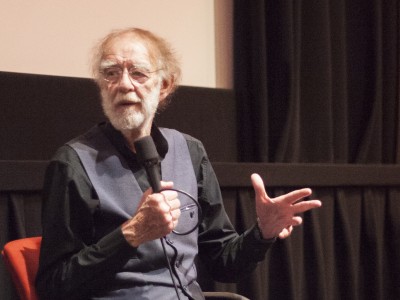

Arboretum Cycle introduction and discussion with Haden Guest and Nathaniel Dorsky.

Transcript

John Quackenbush 0:00

October 15, 2017. The Harvard Film Archive screened four films by Nathaniel Dorsky: Elohim, Abaton, Coda and Ode. This is the recording of the introduction and Q&A that followed. Participating is filmmaker Nathaniel Dorsky and HFA Director Haden Guest. Please note: Mr. Dorsky introduced each of his films, so there will be short breaks between the introductions.

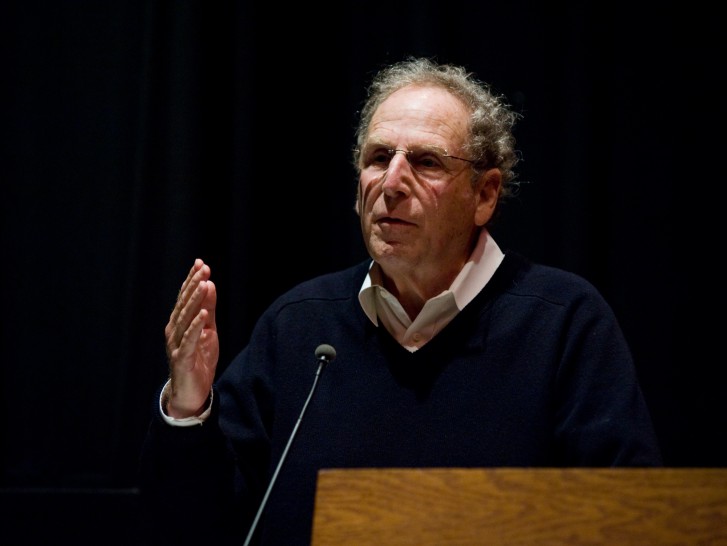

Haden Guest 0:32

Good evening, ladies and gentlemen. My name is Haden Guest. I'm Director of the Harvard Film Archive. I'm here to say just a few words about tonight's very special guest, filmmaker Nathaniel Dorsky, who is certainly one of cinema’s true visionaries. I mean visionary in the literal sense, for Dorsky‘s art is above all, to borrow a phrase from Stan Brakhage, “an art of vision.” Indeed, Dorsky’s films remind us of cinema's unique ability to see the world differently by allowing us to see through other eyes, the eyes of the filmmaker, and the eye of the camera. In Dorsky’s case, the camera is, as it has been since he began making films as a teenager, a hand-held Bolex, with which he continues to shoot 16 millimeter film without sound. Dorsky’s films are lyrical and tonal poems of place, whose striking and contemplative images discover the extraordinary within the everyday, within the streets and parks and cafes of those cities and towns where he has lived, principally his adopted home of San Francisco. What transforms the world seen, captured, and reanimated in Dorsky’s films, is the poetic mode of montage that he’s carefully refined across his long, prolific and still wonderfully active career. Sometimes called polyvalent, or open montage, in Dorsky’s film, the passage from image to image unfolds as a kind of leap, a vertical flight and release that sparks emotion. Even, at times, a kind of ecstasy. This vertical and open movement also is a movement deliberately away from the sort of narrative force and tissue that we are trained to read between images, as citizens of a world ever more crowded with screens and cinematic simulacra. I'm still reeling, I'm still feeling like I'm floating a few inches off the ground because of what happened last night, Jerome Hiler’s marvelous presentation here, his talk, called “Cinema Before 1300” that transformed this theater into a kind of cathedral, a space to contemplate the sacred and narrative art of medieval stained glass, an art form that he subtly argued should be understood as a foundational precursor to cinema. Staring enraptured at Hiler’s slides of the colored pictographic glass, I found myself thinking not only of Hiler’s own films and their rich dialogue with stained glass, but also of Dorsky’s cinema, and the ways in which each image in his films seem to have a shimmering life of their own, a kind of declared autonomy, even while forming part of a meticulously integral whole, much like the jigsaw puzzle, like compositions of the religious windows that contain so many intricate and self-contained images, little worlds of legends and everyday life in the Middle Ages. And like the stained glass, we can say that Dorsky’s cinema is also a spiritual and devotional art, a mode of filmmaking and thinking about film that he expanded upon in his slender yet profound book, Devotional Cinema, which is for sale at the box office, and which is also required reading for anyone interested and invested in avant-garde filmmaking. For while Dorsky’s films are so clearly the unique and meticulously crafted work of their maker, they're also shaped by a certain reverential humility to the world of their making, offering a kind of supplication and tribute to the mysteries and beauty of nature, the seasons, and perhaps, most of all, light itself. Dorsky’s films allow us to see and appreciate and experience this trembling and fleeting world of moments and gestures through which we all too often glide unaware.

Tonight, we are the very lucky audience of four new films by Nathaniel Dorsky, a quartet that may, as I understand, expand into a suite of five or perhaps six films. Though these, like so many of Dorsky’s works, were shot in San Francisco, this set of films are unusual for the fact that they take place entirely within the Arboretum of the city's famous Golden Gate Park. These are films that help us appreciate the reverence for the seasons, that guides so many of Dorsky’s films, and his keen attunement to those textures and emotions invented by each shift of wind and sunlight. Together with John Keats and Ozu Yasujiro, Dorsky should be counted as one of the great artists of the seasons, able to so subtly give us access and understanding of their ever-changing moods and meanings. We're going to see four silent films, and in order to appreciate these together, I'm going to ask everybody to please turn off any cell phones, any electronic devices that you have, and please refrain from using them. Nathaniel Dorsky will introduce the program, but he will also speak, there'll be in the middle of the program, there’ll be a pause after the first two films, Elohim and Abaton and then he'll say a few words then, and then we'll see the next two films, Ode and Coda, and then we will have a Q&A. So now please join me in giving a rousing welcome to Nathaniel Dorsky!

[APPLAUSE]

Nathaniel Dorsky 6:13

Well, it's an honor to be here, this evening being actually a world– maybe even, the universe premiere, of these four films. Those of you who are familiar with my work, I will say that this is a slight divergence from what you might be used to. My films over the last two decades have been working with a continuity of the various, bringing various things together into a continuity. And there's certain problem solving when you're working on that kind of film and I noticed in the last few that I had made, there are some longer and longer sequences, within the polyvalent or varied montage, of a single subject, that begin to deepen, and then they would be suspended between chains of the various. Anyway, when I began to make the first film, Elohim, I said, I've worked with those set of problems enough. I've tried so hard, I’ve worked with them sometimes more successfully than others. But I don't want to quite deal with those set of problems. I want to make a film about one subject. And I had done that earlier in my life. It’s actually, in a way, finding something new was going back to being in my early 20s and how I was approaching cinema at that point, with a single subject, sometimes, of investigation. In this case, the single subject is the light and within the context of the Arboretum, I began the film at the very beginning of February, which for San Francisco, by the way, San Francisco's seasons are a subtle thing in themselves. It might take you a few years of living there to even notice them. They're not at all like the famous New England four seasons. But I began in early February, actually during the week of the Lunar New Year, Chinese New Year, which for San Francisco is actually the very beginning of spring. The very, very beginning. And I contemplated in the garden for a week without my camera. And I finally realized, it was genuine that I didn't want to take pictures of anything in the world. I wasn't interested. The world has been so photographed at this point. We're so overwhelmed with, you know, images of the world. And I don’t know, I just wasn't interested. And I realized what I wanted to do, was make a film, not only about light, but make the film itself an agent of light. Make a film in the garden but have the film actually be one of the growing plants, and a live thing within the garden itself. So I made this film Elohim, which is 31 minutes. And it's more like a Creation, in a sense. And I thought that was going to be the film. But then I finished cutting it, I had the negative sent to the negative cutter, off to the lab. And I just kept shooting. And before I even got a answer print, a release print, what's called release print, back from the lab, I had already shot a half of the next film, which is called Abaton. And Abaton is in Greek, ancient Greece, I guess you’d call it, was a place, there's a healing center called Epidaurus, and other healing centers. And in those healing centers, a lot of the healing was done through dreamwork and various potions brewed up. Some suspect things LSD-related, with wheat and similar sources. But anyway, people would work to heal themselves by sleeping in what was called the abaton. So I, anyway, I just, every film needs a title, and [LAUGHS] so it became Abaton.

Those are the first two we'll see. But before I finished, when I sent that one off to the negative cutter, and then off to the lab, before that could even come back, I was already shooting this next film, which I thought was just gonna be a little addendum to it, called Coda. And that was a shorter one, that's 16 minutes. And then the same thing happened again. It was like chain-smoking cigarettes. So before I got the next cigarette, the next film, whatever they are, then I started the next one, and I called it Ode. And so those are the four we're going to see tonight. And the reason I'm showing it together, each one is very strong. They're very similar, but they're very different from each other, which is sometimes difficult in programming. When things are very different, it’s sometimes easier. But these are similar but different. So it's a little tricky. In fact, to tell you the truth, I've never shown all four together. This is the first time many of them have been shown outside my apartment. So this, in a way, is a test screening. See how we do. But I think that to show four in a row is just not fair to the films or to the audience, and so, I'll come up here and try to do something.

[LAUGHTER]

You know. And, we'll do that. So I should say one thing. These films are like a devotional song, you know, like a song of existence. They're not about at all. They have to do with light affecting your heart. There's no concept going on. It's light and your heart and I'm trying to touch your hearts with the light. So I hope you can enjoy these. I know the projection here is marvelous. Okay, thanks.

[APPLAUSE]

Nathaniel Dorsky 12:58

So, as you can see, the second film was more in the full, the full bloom of spring. In this case, it was actually March and April, which are also very windy, very windy months in San Francisco. The air, ocean, the wind keeps blowing in from the ocean the entire time. So, that was Abaton. After this point, just like in life, this glory of youth, reproduction and passion, there becomes tinges of mortality.

[SOMEONE COUGHS]

Oh! [LAUGHS]

[LAUGHTER]

Become tinges of mortality. You as human beings will begin to brown at the edges, and things like that. And Coda is a little bit, first introduction after all this pure passion, passion of reproduction, into the more, shall we say, knowledge and seriousness and the first glimpses of mortality. So that was a little bit of the atmosphere of Coda, which is then followed by Ode. And what is Ode? Ode is more like a song of the beginning of the end of your life, the beginning of death, in a way. The color red and the plants become more red, and so forth. I have already finished a fifth one I called September, which, believe it or not, was September. And September is Indian summer, a very ripe time before, before the...like today. The kind of ripeness of today, before the end. And I think I'm going to do a sixth one, so it'll become a full cycle of the year. So I guess we'll just go on. I don’t know if there's anything else to say right at this point. The Coda is 16 minutes. And Ode is like 20 minutes.

[NOTE: THESE TWO SEGMENTS BRIEFLY OVERLAP SO HADEN GUEST IS SPEAKING OVER DORSKY.]

Haden Guest 15:27

Please join me in welcoming back Nathaniel Dorsky.

[APPLAUSE]

So before taking questions from the audience, maybe we could just start right here. And you declared beautifully at the beginning that light was, you know, one of the subjects of the film. And one of the ways you announce and explore that, across these four films, is this striking way in which you allow the light to merge slowly into the image. And then at times, there’s this gestural flare! And I'm wondering if we could talk about this, the sort of expressive use of light. In some ways, it seems to be declaring the camera to be at work here, but also it seems to be speaking to our own eyes, the ways in which we're suddenly struck by this dazzling light, we're reminded of how our eyes, like the camera, must, in fact, dilate and things like this. So I was wondering if we could talk about this gesture that we see throughout the films.

Nathaniel Dorsky 16:34

Well, I think part of it is, oh, dear! [LAUGHS]

Haden Guest 16:39

Take this wherever you want.

Nathaniel Dorsky 16:40

No, it was very intuitive and I think because I was making a film about one subject. And also, the nature of my photography, it has a kind of, what is called painting-all-over quality? It’s all over, so that you can rest your mind on it. And then, how do you make a film that progresses, which is a progression of all-overs? It wouldn't work. So I had to develop a kind of internal language. You know, I just had to, it was quite intuitive. And I would get into the groove, so to speak. And I would be with the camera, and the wind would start, and there were just times when I just wanted to expand. It was pure, I don't know, you know. I just would want to expand, and then darken, and just, you know. I can't say any more than that.

Haden Guest 17:46

It gives the images a kind of breathing..

Nathaniel Dorsky 17:48

Yes.

Haden Guest 17:49

...a breathing quality as well.

Nathaniel Dorsky 17:51

Also, because film emulsion is in a vulnerable state now, of how much longer it'll go on. There’s a desire to celebrate the emulsion and show what it can do, in its various aspects, and how the same image can be like ten different images. And it can hit all different spots and that beauty within the curve of the emulsion. It's very much, I think, also a swan song to cinema. Like, very few people are shooting film and finishing in film. And it's been 120 years, whatever, of human culture, neglected instantly by the newness of digital convenience. And I want to leave something in the world for young people. I want to leave them a touchstone of analog, a touchstone of something material.

Haden Guest 18:56

And also, though, with film, the film emulsion is something organic, and here speaking intimately to this organic world. And, for those of us who know your films and have seen many of them, realize how striking it is, the absence of human figures in this film, and this focus entirely on the plants. So I think that's something quite remarkable.

Nathaniel Dorsky 19:21

Well, I hope that people in the audience realize at a certain point that they're the character. That it is, there is a character in the film. It's you! [LAUGHS] You know? [LAUGHS]

Haden Guest 19:34

No, indeed, I mean, we are thrust deep into this forest.

Nathaniel Dorsky 19:38

Yeah.

Haden Guest 19:40

I'll ask one more question, then we'll take some from the audience. I wanted to ask about also the striking use of play with focus, I think. And I want to thank our, our skilled projectionist, John Quackenbush, for never losing a beat, because this is, in fact, a really challenging...

[APPLAUSE]

Oh yeah! Thank you.

[APPLAUSE]

He's taking a bow. But-

Nathaniel Dorsky 20:02

Also, I promised to defend his reputation. I asked him to play the leader on the screen.

Haden Guest 20:07

Yeah!

Nathaniel Dorsky 20:08

As an, as an entr’racte between the films. So he would normally, as a good projectionist, would cover that up. And I said, let's, I just think it'll serve as a palate cleanser, in a way.

Haden Guest 20:21

Right.

Nathaniel Dorsky 20:21

Producing the script, and all that, and the leader. Yeah.

Haden Guest 20:24

But just to continue with this line about, about the focus, though. There's these gorgeous moments where we almost seem to have these autochromes. Where we see the flowers, or sort of the color, with almost this painterly palette. And I'm wondering is, then these, too... this was also an intuitive,...?

Nathaniel Dorsky 20:43

Well, I'm trying to, like in all my films, I'm trying to move people away from language. And nurture in them a more primordial, can one say more primordial? Is that like more unique? Or do you just say primordial?

Haden Guest 21:04

Stick with primordial, yeah.

Nathaniel Dorsky 21:05

Yeah. You know, give the audience, communicate to them, to their subtle body, to the primordial being, rather than language. What I was saying last, I guess, in the Brakhage introduction, how language has to do with survival, survival of the ego, survival of identity, survival and paying your rent. And I didn't want the images to be about survival and certainly not a depiction of a garden, which could be quite a dull movie.

Haden Guest 21:45

Let's take some questions from the audience. I'm sure there are some. So if you have any questions. Here, we'll start right down here in the front. If you have a microphone, you can please bring it down? If you want to raise your hand, the question. There you go. Thank you.

Nathaniel Dorsky 22:07

It’s not on, is it?

Haden Guest 22:08

Turn it on? Yeah, it’s on.

Nathaniel Dorsky 22:11

Oh, yeah. I'm not on! [LAUGHS]

Audience 22:17

You sort of touched on my question in your comments now. But I was, throughout these films, wondering about the role of ambiguity in your image making. I find myself most entranced by your work when I don't know what exactly it is that I'm looking at. And fortunately, that's quite often. But with this film, in particular, as the Archive Director mentioned, a lot of the shots, you know, began as underexposed or out of focus and then very gradually became more legible in a sense. And that progression towards legible, from darkness to light, was completely intoxicating. And I'm just wondering if you had any thoughts on this kind of progression from the ambiguous, the less ambiguous, from darkness to light?

Nathaniel Dorsky 23:02

Sounds like life. [LAUGHS]

[LAUGHTER]

Haden Guest 23:12

Well, can….

[LAUGHTER]

Nick, you spoke about emulsion, and I just wondered if we could deepen that just a little bit, because we mentioned the vulnerability, right? Of film as film. But you've had very intimate relations with certain emulsions, so to speak. And I was wondering if you could speak, maybe more technically, about what are you working with now in these films? And what kind of relationship do you have with this emulsion? I say that because I know sometimes you've entered into the adventure of making a film with a new emulsion, not knowing exactly what it is you're going to, right?

Nathaniel Dorsky 23:49

Yeah. Well, for many, for most of my life, I shot a reversal, Kodachrome. And I had Kodachrome in my psyche, I could look at something, I’d know how it would look in Kodachrome, I don't use a light meter, ’cause I've been doing this since I was 12. So this is a light meter. So I don't use a light meter, but I can, but when Kodachrome got cancelled, and I had to start to shoot with color negative, the first three or four films are, they’re nice, but they’re a little shaky. I couldn't feel them anymore. I felt like a jeweler who’d been working with gold, and was now, you know, working with tin, or something. But then, eventually, I began to find and discover the beauty of the color negative. Like which colors you can overexpose, and have them beautiful, which ones would become ugly if you overexposed, which were dark. So begin to learn it, and then, like a lover, we came to know each other more, and could go further places. You know.

Haden Guest 24:55

Other questions or comments? Yes, right here in the front. Here comes a microphone, to your left.

Audience 25:07

I just have two quick questions. Do you do still photography at all?

Nathaniel Dorsky 25:12

Oh, with my telephone. Yeah. [LAUGHS]

[LAUGHTER]

Audience 25:17

What kind of phone do you have?

Nathaniel Dorsky 25:19

Pardon?

Audience 25:19

What kind of phone do you have?

[LAUGHTER]

Nathaniel Dorsky 25:22

A 4S? I just got a new one for fifty dollars.

[LAUGHTER]

Audience 25:31

My second question is that I've seen it mentioned a few times that you make a living as an editor?

Nathaniel Dorsky 25:36

Yes.

Audience 25:37

What kinds of things do you edit, or whose things do you edit?

Nathaniel Dorsky 25:41

Well, in a way, it's like asking a house painter, what kind of house do you paint. You know?

[LAUGHTER]

You know, as an editor, you edit every– Give it to me. I'll edit it. [LAUGHS]

[LAUGHTER]

You know. But I said, I’m gonna say, the documentary form... Because the Bay Area kind of a, I don’t know if you’d call it a hot bed, a warm bed of..

[LAUGHTER]

...or a lukewarm bed of documentary filmmaking. And so a lot of times I work on documentaries. Sometimes they're great. Sometimes they're quite ordinary. But then, this year I worked on two or three features, and some other experimental films. I'm just an editor, so [LAUGHS] whatever it is, I try to make it work better for you, you know? People have called me up said, “Well, would you be interested in this subject?” And I said, “I don't care about your subject. I'll make it better.” You know?

[LAUGHTER]

Haden Guest 26:48

Other questions or comments for Nathaniel Dorsky? Let's go to the very back. If actually, yeah, if you could use the mic, that’d be great.

Audience 26:59

On the same note of editing, were there any basic concepts that determined your own editing? Was it just color that motivated you to cut, and when?

Nathaniel Dorsky 27:08

Oh, in the films we saw tonight? It was the whole thing. It was the whole thing. Yeah, there was no one thing. It’s the whole thing. Do you know what I mean? [LAUGHS]

[LAUGHTER]

Like life. Ya know. [LAUGHS] The thing is, I'm interested in how do you make a film go forward, of this nature, that has no character or no story? Right? And it's for you, it's for your psyche. So in a way, it's like, giving the audience a kind of a massage, so to speak. In other words, you contract, you release. You know, you do all these things to offer them pleasure. You know, hopefully it's pleasurable. If this film isn't pleasurable for you, I think sometime it might become pleasurable. To me they're quite pleasurable. It’s that simple. You know?

Haden Guest 28:16

Other questions? Let’s take this gentleman right here.

Audience 28:27

Hi. Similarly on the note of editing, I was wondering, for these films in particular, in the process of kind of unpacking whatever structure was there to the, to each of the films, did you most often begin with one really striking moment, or striking image, and then kind of unpack that? Did you consider the material, all the footage, as a whole first? I'm just kind of wondering in what, what kind of the process looked like for unpacking the structure of all these.

Nathaniel Dorsky 28:57

I hate packing. [LAUGHS] It's always gets me depressed to pack. And I guess unpacking’s more fun.

[LAUGHTER]

What are we talking about? I forget.

[LAUGHTER]

What are we talk-, packing, unpacking, then what?

Haden Guest 29:21

Well, finding a structure...

Nathaniel Dorsky 29:22

Oh, oh, oh yeah, that's right. All right, so I get the footage back, and I take out what's terrible, right? Then I take out what's good, and then I take out what's very good, and then I take out what's excellent. And finally, you're left with the shots that have a kind of a soul, a life to them. And then they're in the chronological order that I shot them, just because you’ve eliminated. Then there's a different shift in the editing. After that stage, then you have the material to work with. And the film begins to declare its own tone, at that point, as you take out what's not good. And the film says thank you, thank you. You have to help the film, and the film helps you. And then the film declares itself. You look at a shot and you say, this feels like the beginning, and you just move it over here. And this is really strong, but we shouldn't, I don't want to feel it, too, I need it around the 80% point, it should be over here. So I take it and move it here. So I slowly move things around, and the film tells me if it's working. And sometimes it's impatient. You know, sometimes I don't put a shot in the right place for a long time. Then finally I do, and they're very happy to be in the right place. You know? Just like that. I've been doing this all my life and at a certain point, if you do something all your life, your brain is very good at it. You know, your brain is smarter than you are. You know, you're kind of dumb, but your brain’s smart. And so I just let my brain work. You know? I do the work, but the brain tells me what to do, you know? It becomes much more like, it’s wonderful! The only good thing about getting older is that. [LAUGHS]

[LAUGHTER]

You know, is that you get good at something. Not good at something, your brain gets good at something, and you respect that your brain can do it.

Haden Guest 31:28

Other questions? Right here in the center. Coming to your other side.

Audience 31:39

Thank you very much. I was just wondering, were there any particular times of the day that you found yourself going there? Like, just out of curiosity.

Nathaniel Dorsky 31:48

Well, in the very first film, when it’s February, by three o'clock, the sun is dipping down into the trees, you know. So you go in the middle, you know, the middle of the day is already, and then by the time you're, the last film, you know, say that's June, you know? Then the light’s, you know, like, after about three o'clock, you know, it starts to get a little more character. The color negative seems to respond more nicely when there's a little more warmth in the light. That’s what I noticed. Yeah.

Haden Guest 32:30

There was another…no? Any final questions or comments for Nathaniel Dorsky? If not, we thank you for this wonderful evening and we're gonna be signing books out at the box office!

[APPLAUSE]

©Harvard Film Archive

Related film series

Explore more conversations

Ang Lee

Alfred Guzzetti

Godfrey Reggio & Ray Hemenez