Do It Only If It Burns When You Don't. Anand Patwardhan’s Film Activism

During the Cold War it was said that an iron curtain prevented information from getting in or out of the Communist Bloc. Today a velvet curtain of mindless infotainment envelops the globe enforcing a strict censorship of the vital stories of our times. – Anand Patwardhan

The films of Anand Patwardhan document the rise of religious fundamentalism and inequality in India over the last five decades. A fierce documentarian and activist, he has faced legal battles, censorship and threats of violence throughout his career. These hurdles have not deterred him from making films that tell the stories of India’s underrepresented minorities to expose the arbitrary, everyday violence directed against them. Patwardhan’s films possess a restless energy that is meant to provoke, inviting the viewer to listen to those who are in pain, and become unsettled with the current state of the world. By opening up the space to collectively reckon with the anger and frustration generated by systemic injustice, Patwardhan’s cinema of activism brings urgency to the work of building a better, more humane future.

Anand Patwardhan’s exposure to progressive politics began at an early age. Born in 1950 in Mumbai, he grew up in a family that participated in resistance against British rule and supported Mahatma Gandhi’s campaign for India’s independence, and Dr. B.R. Ambedkar had lived with the family on visits to their hometown. (His role as the leader of the Dalit people is a key subject of several of Patwardhan’s films.) Patwardhan received a B.A. in English Literature from Mumbai University in 1970 and a second bachelor’s degree in Sociology from Brandeis University in 1972. At Brandeis, he joined his professors and peers at anti-Vietnam war protests while the movement was it its peak. Through this experience, Patwardhan became initiated into a life of activism. He recalls, decades later, about the influence of American intellectuals and civil rights leaders, such as Martin Luther King, on him: “It was the lesson that set me free.” Working in rural India in the early 1970's, the Emergency forced him to flee to Canada where he made a film and received an M.A. in Communication Studies from McGill University in 1982.

From Bombay, Our City (1985) to Reason (2018), Patwardhan’s visual style has undergone a radical evolution, but his journalistic ethos and warrior-like courage in the way he approaches his subjects remains a through line. In each of Patwardhan’s films, one could find interview sequences shot from the middle of a crowd: at large events, in the streets, or even in a cramped room where tension builds around Patwardhan’s very presence. In the Name of God, for example, contains a scene of a tense exchange between Patwardhan and a group of Hindu worshipers who want to remove the Babri Masjid Mosque against the will of their Muslim neighbors. In Reason, Patwardhan is threatened with violence in public by representatives of a religious fundamentalist group. Another hallmark of his style is the masterful use of found footage from television, infomercials and other forms of mass media. By reappropriating material that has already circulated in popular consciousness, Patwardhan crafts an emotional appeal with the aura of objective truth to deliver what he calls “the vital stories of our time.” For his work spanning over half a century of filmmaking, Anand Patwardhan has received accolades from festivals and institutions both at home and abroad, including Cinéma du Réel, Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival, the IDFA, and so on. Although he has won the prestigious National Film Award multiple times, his films are still subject to censorship in India.

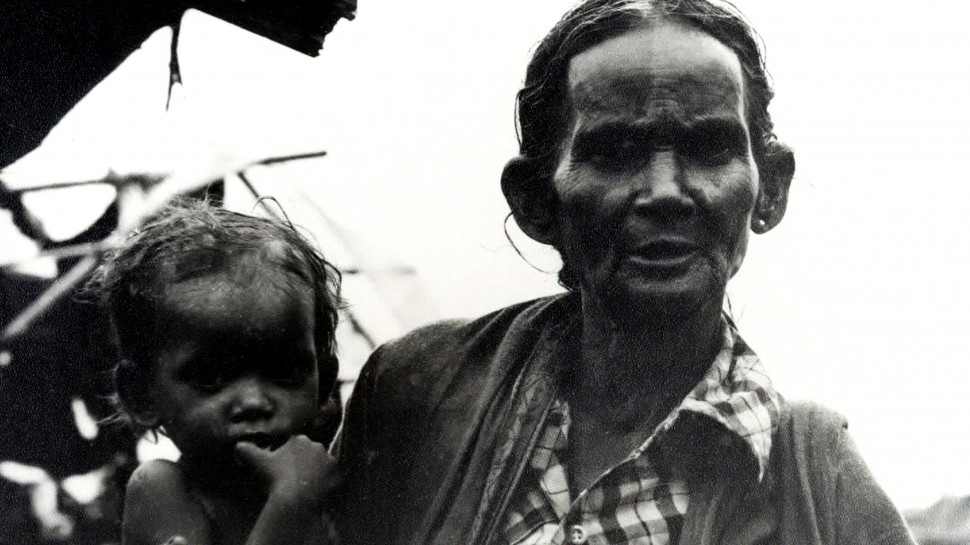

The contradiction between official recognition of the importance of Patwardhan’s work and the bureaucratic quagmire that prevents it from circulating to the general public is part of what he has to reckon with as a filmmaker-activist. When the national television channel Doordarshan rejected Bombay, Our City for broadcast without clear justifications, Patwardhan went to court to challenge their decision and won. Not only platforms for minority voices to reach a wider audience, Patwardhan’s films are media objects; projectiles that disrupt the media landscape and launch these voices into the spotlight. In 1986, when Patwardhan was nominated for a National Film Award for Bombay, Our City, he asked a slumdweller who appeared in the film to receive the award on his behalf, using it as a tool to raise awareness of the hardships she and her community faced. His latest film, Reason, was never submitted to the censorship board and thus remain unreleased in India. Instead, it is shown at clandestine screenings in university halls, where students can buy DVDs of the film from the director himself.

Armed with the tools of a documentarian, Anand Patwardhan has relentlessly confronted hatred and ignorance by joining his voice with the voices of those speaking out against their own mistreatment. He speaks alongside slumdwellers of Bombay, Muslim victims of religious violence, Dalits who have been fighting against the inhumane caste system, and family members of intellectuals who lost their lives criticizing the excesses of religious indoctrination and superstition. The voices are saying: “I am alive, I am innocent, and I share this space with you.” These should not be contentious words, and yet they are routinely dismissed and suppressed. Hatred is an enigma that frustrates and enables indifference. One way it could be stopped is by holding leaders accountable for their actions and words. However, Patwardhan understands that it can only be confronted on the individual level. It is in his power as a filmmaker to initiate the process by asking pressing questions and uncovering uncomfortable truths. – Ton-Nu Nguyen-Dinh