The Reincarnations of Delphine Seyrig

The remarkable first-to-second-act trajectory of Delphine Seyrig’s career has, in recent years, come more fully to light in cinephile communities worldwide. The triumph of Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles—which topped the 2022 Sight & Sound poll of the greatest films of all time, and which features Seyrig (1932-1990) in the title role—brought attention to her pioneering collaborations with female directors. Meanwhile, new restorations of Seyrig’s directorial efforts and a key exhibition at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía dedicated to her involvement with French feminist video collectives of the seventies and eighties have illuminated her radical creative spirit and lifelong commitment to activism. Still, her career tends to be defined along the same narrative: she was a muse to European auteurs like Alain Resnais, François Truffaut, Joseph Losey and Luis Buñuel before repudiating her goddesslike image and pursuing collaborations that challenged and complicated the feminine persona that made her a star.

Reincarnations reframes the French-Lebanese actress’ body of work and breaks it out of this before-and-after template. With over forty performing credits to her name in film and television movies, Seyrig was an industrious and intellectually curious artist whose tastes were complex, rooted not only in her feminism but also in her expatriate-bohemian upbringing and her early years in New York City’s theater and arts scenes. Before emerging as the face of Alain Resnais’ Last Year at Marienbad, Seyrig was, essentially, a struggling actress: she had a decade of experience as a stage performer under her belt, had taken courses with Method-pioneer Lee Strasberg, and had played a bit part in a Beat Generation short film (Pull My Daisy, directed by Robert Frank), but remained virtually unknown before Resnais whisked her back to Paris, where she would live and work until her death from lung cancer in 1990.

Last Year at Marienbad was Seyrig’s big break. Already twenty-nine when the film premiered at the 22nd Venice International Film Festival in 1961, she was discovered at a relatively late age compared to other iconic French actresses at the time and was immediately sought after by leading directors in Europe and Hollywood. Fluent in English, French and German, Seyrig was hailed as “la divine” by French critics for her elegant persona, which recalled the enigmatic dream-women of classic film like Greta Garbo. Several of her most well-known roles (such as the one-time lover of Antoine Doinel in Truffaut’s Stolen Kisses) played upon this feminine archetype. Marienbad—or, more specifically, the buzz around it and the chic modernity of Seyrig’s look and costuming—was in many ways responsible for creating this box around her. Yet the film also introduced Seyrig as an actress eager to experiment with performance styles, one whose command of her craft was already sophisticated; thus the eerie depths she plumbs with an entirely wordless performance. Though several of her early works demonstrate her avant-garde proclivities and her fearless, open-minded approach to acting, she eventually came to resent her popularity among big-name directors (“I became a sort of status symbol—hired to create a link with another great director and not a choice for myself,” she said).

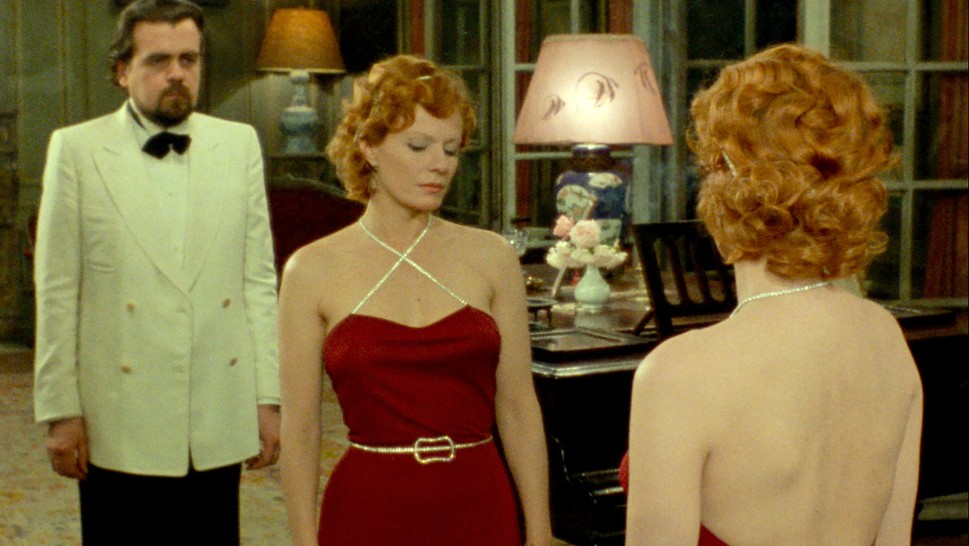

Seyrig was the rare actress who could simultaneously transform into someone unrecognizable and maintain her star’s essence: from the beginning, she was able to play older women with matriarchal aplomb, or playfully plastic gals with hidden agendas; bring to life classic, well-trodden roles like the fairy godmother or the femme fatale with her own signature spin. No matter the guise, her gentle, smoky vocals announced her as Seyrig, and though she increasingly bucked her association with all things timeless and ethereal, she also manipulated this image to expand upon its possibilities and upend the foundations of her own iconic status (as in Daughters of Darkness and Dorian Gray in the Mirror of the Yellow Press).

At the beginning of the seventies, Seyrig started attending meetings of the Mouvement de libération des femmes (MLF), becoming a vocal advocate for abortion rights and equal pay, and speaking about the movement’s concerns on television and in public trials. The films she made as part of the feminist video collective Les Insoumuses (“the defiant muses”) will be screened in this series, though several unrestored short works (about women’s rights struggles abroad in Vietnam and Brazil) could not be included due to their poor condition.

Reincarnations privileges Seyrig’s collaborations with female directors like Akerman, Marguerite Duras and Ulrike Ottinger, as well as other women whose work has largely been neglected by official film histories—like Liliane de Kermadec and Pomme Meffre. This alternative take on Seyrig’s oeuvre paints a different picture of her powers and range: if she were easily cast as an object of male fantasy, she also just as frequently played characters with great fantasies of their own, women teeming with heartache and regret and the memories of their previous lives. Through this lens, Seyrig was a timeless performer not because she conveyed an unrealistic kind of femininity, but because she seemed to carry the past in her bones, always embodying a woman of multiplicities: expressive yet controlled; wise to the ways of the world and the realities of modern womanhood yet breathlessly romantic; capable of great cruelty yet warm and maternal. – Beatrice Loayza