Fellow Traveler: The Cinema of Warren Sonbert

Warren Sonbert (1947-95) made a series of unique, exhilarating films that juxtapose the everyday and the exotic with touches of abstraction (and even, occasionally, hints of narrative), all held together by a very original style of montage.

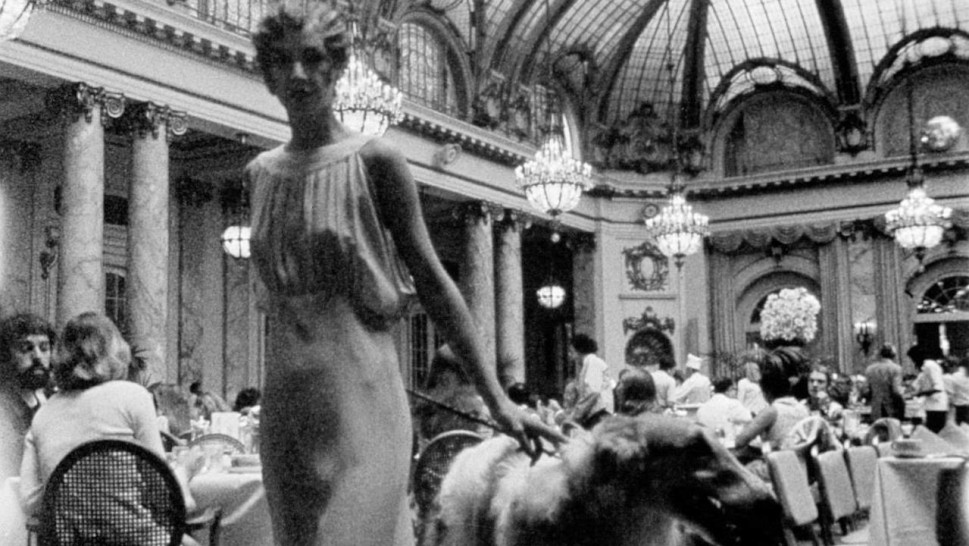

A protégé of Gregory Markopoulos, Sonbert— visibly inspired by Warhol and Anger—made his first films while still a teenager in 1960s New York. A series of events at the end of that decade prompted a shift in Sonbert’s filmmaking: his move to San Francisco and away from the Factory/art-world scene (whose denizens people Sonbert’s New York films) and trips to London and north Africa, the first of many voyages made with his 16mm Bolex camera. By the end of his New York period, Sonbert had eschewed sound to make The Tuxedo Theatre, his first purely montage-based film. For the next twenty years, Sonbert would work exclusively in this style, making a film of roughly 30 minutes length every few years.

Sonbert was also a teacher of film and a critic who regularly contributed program notes for the Pacific Film Archive and reviewed movies and opera for the Bay Area Guardian and the Advocate. During his frequent travels, either in his guise as an opera critic or else to present his films, Sonbert always brought his Bolex. As he honed his filmmaking style, certain kinds of images began to recur as motifs throughout his films: parades, animals, fireworks, bridges, circuses, flowers and, above all, shots of or from all kinds of means of conveyance: cars, planes, trains, carousels, surfboards, roller skates. Sonbert’s ten films from 1972 to 1995 (nine of which are included in the HFA program) offer subtle variations on his approach to editing, which has been compared to the rhythmic poetry of the classic city-symphony films and Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera, but without their geographic or temporal parameters. In Sonbert’s films the spectator’s perspective is reset every few seconds, from inside to outside, close-up to long shot, New York to India. And yet, for all that Sonbert’s films play with cinema’s magical ability to whisk us from one place to the next, their scale remains distinctly human, restricting abstract or ostentatious spectacle.

Interspersed among the many images of public events gathered in Sonbert’s films are private moments of friends seen at home or at work. Somewhere between the public and the private lie the numerous images of heterosexual couples so central to Sonbert’s films—glimpsed kissing in the street, getting married, or captured in quiet reverie. Sonbert lived quite openly as a gay man—his first film, Amphetamine, shows a gay couple shooting up and making out—and gay men appear frequently in his films, particularly at gay pride parades and ACT UP demonstrations. The fascination with straight couples seems to have both a cinematic impetus, given the centrality of heterosexual romance to the classical Hollywood cinema that Sonbert so loved, and a political one, given the emphasis on weddings (especially in conjunction with Sonbert’s admiration for the films of Douglas Sirk, and their subtle critique of marriage and family) and the recurring presence of various government buildings, churches, and men in uniform in Sonbert’s films, as well as titles like Honor and Obey, Divided Loyalties and Friendly Witness. In other words, Sonbert’s films share with Hollywood melodrama a concern for the ways that social forces work on private lives.

By the end of the 1980s, Sonbert had relented in his previous stance against sound in cinema, and began once more to add soundtracks to his films, incorporating pop and classical music as he had in his work of the 1960s. At the same time, as the AIDS crisis decimated gay communities around the world, Sonbert’s films grew more somber and political. At the time of his death from AIDS-related complications in 1995, Sonbert was editing his last film, Whiplash, with help from his lover Ascencion Serrano.

Sonbert may be the ultimate bridge between the school of Bazin, built around cinema as pieces of real time and space, and the school of Eisenstein, which declares the essence of cinema to lie in the juxtaposition and concatenation of images. Sonbert himself took a harsh (and arguably inaccurate) view of Eisenstein, but all the better to honor his hero Vertov, whose own montage-based documentaries are certainly a better comparison for Sonbert’s than Eisenstein.

Sonbert’s films have been preserved under the auspices of the Estate Project for Artists with AIDS. The Estate Project’s film preservation program was developed under the guidance of Jon Gartenberg, and the films were preserved in conjunction with the Academy Film Archive. With this preservation now completed, and with a chapter devoted to Sonbert in P. Adams Sitney’s important new publication Eyes Upside Down, the time is ripe for a reappraisal of Sonbert’s major contribution to American avant-garde film culture at the turn of the millennium. In the spirit of Sonbert’s view of cinema as encyclopedic (he wrote, “I believe that the nature of film lends itself to density: one can’t pack in too much, albeit with rests, breathing spaces.”), we present nearly all of Sonbert’s films, in four programs spread over three days. This program also coincides with the HFA’s acquisition of a complete set of prints of Sonbert’s films, realized through the generosity of the Roby fund of the Harvard College Library.