Furious Cinema '70-'77

“Nobody knows anything.” That’s William Goldman’s famous line from his 1983 memoir, about working in movies in the 1970s.

And watching the movies from that period, that crazy worldwide flowering of ballsy cinema, you can see that it was true. Nobody really did know anything. The producers and money-men didn’t have a clue; the marketing departments were lost; the film critics weren’t sure what was going on; and often the “heroes” onscreen knew less than anybody. And it was glorious, because they were willing to try just about anything.

Maybe we’ll never recapture that moment. Maybe we all just “know” too much now. But back then—with the fences knocked down, the maps torn up, the gates left ajar, the governors on the engines disabled—cinema exploded. It was a time of furious announcements, furious experiments, furious rebellions, furious mistakes.

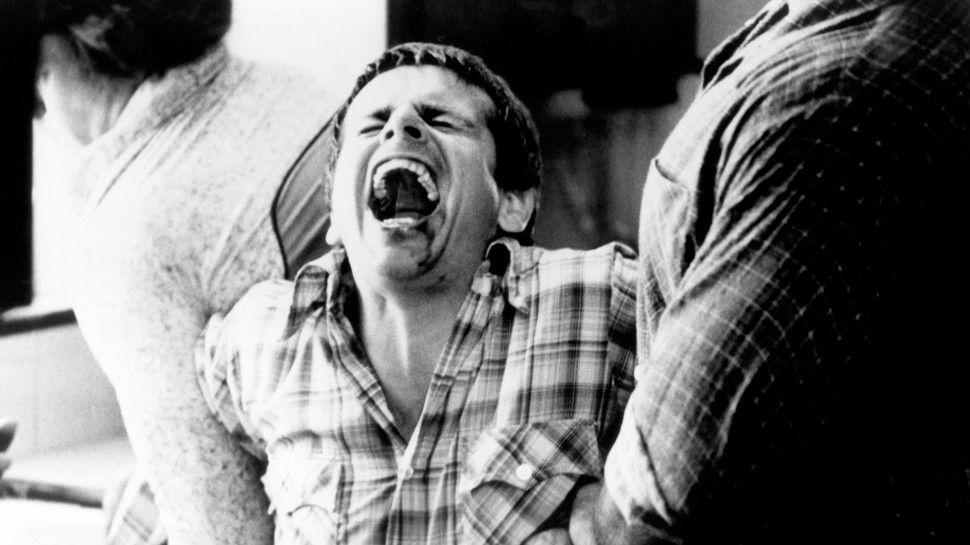

And it was all the various engineers of filmmaking that were in revolt against “the way things are done.” Actors were swallowing their lines, stuttering, mumbling, ignoring the camera; allowing themselves to be underlit and unglamorous. Editors were cutting scenes abruptly, intercutting unexpectedly, using their Steenbecks like a muscle car to push audiences around. Sound was being recorded now by body mikes, allowing actors to move around freely, talking loud or soft, interrupting each other: not waiting for a boom to swivel towards them. Telephoto lenses and maneuverable cameras turned cameramen into eavesdroppers, or spies, or scientists with a microscope, exposing the biological truths of faces and landscapes.

What’s remarkable is not just that they did these things, but that the money allowed them to. The common idea about movies is that they can never be a “pure” art form like painting or novels, because they’re so expensive: so the people with the money will always be looking over the shoulders of the creatives, hamstringing them. But when the people with the money don’t know anything, the balance of power shifts. The money-people look back at the directors and say with a shrug, “well, it beats me. Maybe the kids will like it. Go ahead!”

The money-people might have been scared, but the directors and the writers and the actors seemed fearless. You could make films about losers, neurotics, assholes, or outcasts. You could make movies where all the characters are played by dwarfs. You could make detective films where the detective detects nothing. You could make Westerns about the lone, self-reliant man, where the lone self-reliant man gets crushed by the railroads, or disappears into the landscape like dust. You could shoot and edit your film to feel like a drug trip, while you and your crew took a drug trip behind the camera.

Maybe the whole thing only happened because of the kids. Kids are difficult to understand, in general. But in 1969, when society seemed to be ripping itself to shreds, and the generation gap was a yawning crevasse, they must have seemed an economic enigma. The studio people had no idea what to do—but they knew they had to do something. Because the kids did have money to go to the movies. A lot. But were they going to 2001 because they liked the chilly evisceration of man’s dependence on technology? Or because they liked to lie down on the floor during the last half hour and smoke joints? Were they going to Bonnie & Clyde to see rebellion against the social order, or to see cool outlaws being shot in slow motion by way too many bullets? Were they going to “Easy Rider” because they liked an existential story of lost men in a broken nation, or because they dug the Steppenwolf song and watching movie stars smoke pot onscreen?

Easy Rider’s marketing posters declared, “This Year, It’s Easy Rider.” What phony bravado! In reality, it seems like the posters for every film released during those years could have used the same tag line, but phrased as a question: “This year, is it Carnal Knowledge?” “This year, is it Two-Lane Blacktop? Is it perhaps Clockwork Orange? Harold and Maude? Does anybody know what it is? Can anybody help us?”

It was largely Europeans who had planted the seed. Those euro-heroes of the 1960s—in France, in Italy, in Sweden—had reinvented cinema with their fearless and passionate experiments. And now, worldwide, the film directors of the 1970s were the teenagers of the 60s who had watched those films, and been inspired, instigated, infused. With their newfound freedom, they would repay the debt tenfold.Like many revolutionary movements, the Celluloid Spring didn’t last. By the 1980s, the money-men had crushed the revolt, repaired the fences, restored order. The business of movies was business once again. Predictable, scientific. We may never recapture those furious days. But the films are still with us, and so the dream of the revolution can live on: a torch passed from audience to audience, from director to director. Furious cinema lives! – Athina Rachel Tsangari, Department of Visual and Environmental Studies Visiting Professor