Audio transcription

Unknown Speaker 0:00

September 28, 2014. The Harvard Film Archive screened films by Oskar Fischinger. This is the audio recording of the introduction and Q&A. Participating are Haden Guest, HFA Director, and Cindy Keefer, Director of the Center for Visual Music.

Haden Guest 0:23

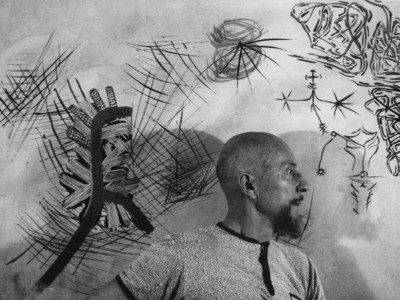

Good evening, ladies and gentlemen. My name is Haden Guest. I'm Director of the Harvard Film Archive. I'd like to remind everybody to please turn off any cell phones, electronic devices that you have, and please refrain from using them during tonight's show. I'm really thrilled that we are able to present this very special exhibit of Oskar Fischinger’s extraordinary, mesmerizing, and really pioneering films. Fischinger was a pioneer, not only of experimental animation, as he’s often celebrated, but also, really, one of the pioneers of abstract art. I mean, he is a towering figure of the 20th century Modernist movement. And I think he is all too often seen strictly within the realm of cinema and animation. In truth, his legacy, and his influence, extends much, much further than that. We are presenting this program together with the Center for Visual Music, and the Curator and Archivist of CVM, as it’s often known, Cindy Keefer, is here to introduce this program. Cindy Keefer works tirelessly to promote the work of Fischinger, Jordan Belson, and many other figures whose films and legacy are entrusted to the Center for Visual Music. Miss Keefer was here at the Harvard Film Archive, some of you may recall, with a really wonderful show of the films of Jordan Belson. And that show, as with tonight's show of Fischinger’s films, and tomorrow night's screening of films by Mary Ellen Bute, includes and showcases many titles that have been preserved by the Center for Visual Music. And this is really very, very important work that they're doing. They're doing film-to-film preservation. So we're going to be seeing these films in their original format, in 35mm, 16mm, and lovingly and painstakingly preserved. So please join me in welcoming Cindy Keefer!

[APPLAUSE]

Cindy Keefer 2:39

Thank you, Haden. I also want to thank David, Brittany, and all at Harvard Film Archive that made this screening possible. And I want to thank CVM’s members, who make our work possible. And I know we have some CVM members in the audience, and thank you.

I want to say a few things about CVM and our work first. And I'll mention, though, that tonight is all 35mm prints, which was Fischinger’s original format. Tomorrow night, the Bute screening is 16mm prints. And it is all on film, we still do preserve, expensively, on film. We do transfer to HD and to digital for access purposes, like museum exhibitions. But for these kind of screenings, we tend to show the original format whenever possible. Center for Visual Music has distributed this retrospective program, Optical Poetry, for many years now. I think it's been around the world twice. These are all on restored and new prints. It’s screened worldwide, at museums, archives, cultural centers, and festivals, literally worldwide. The prints were preserved by CVM, some by the Academy Film Archive, they preserved a few back in the 90s. One was preserved by EYE Film Amsterdam, and you'll notice the head of Studie Nr. 8 has a Dutch title on it. But everything except for that one comes from the CVM collection, and they're much more recent preservations. This is a new restoration we're going to see tonight of Studie Nr. Five, and it's a new restoration of Spirals. There are many more Fischinger films still to be properly preserved from the original decaying nitrate, and then digitized. So we're constantly grant writing and fundraising, as film preservation is an ongoing process, a race against decaying materials. Plus, I should add, for any Jordan Belson fans in the audience, we now have dozens– [SCATTERED APPLAUSE] oh great! We now have dozens and dozens of reels of Jordan’s tests and experiments that we're working to save. Basically, I cleared out his entire studio in San Francisco, every little tiny scrap of film, every little experiment, everything he ever did. We now have an entire vault full of that to restore, too.

So, CVM, a basic intro about CVM. We're a nonprofit archive dedicated to visual music, experimental animation, and abstract cinema. Our major collection is the work of Oskar Fischinger, and also Jordan Belson. And we also have the work of Mary Ellen Bute, Charles Dockum, and others in the history of visual music, plus some contemporary work. We've licensed Fischinger films, and distributed the Fischinger DVD across all seven continents. The Fischinger DVD is even in Antarctica now. We donated it to a science center down there. So we are on seven continents. So we continue to make the work accessible through a variety of access programs—screenings, DVD releases, a new book, museum exhibitions—and we have some online clips on our Vimeo channel. If you like the show tonight, and you go on to YouTube tomorrow to find Fischinger films, you won't. There are no authorized Fischinger films on YouTube. Even though people say these are Fischinger films, they're not. There's one faded pink one. So go to Vimeo, where you will see authorized, real Fischinger films. CVM’s talks, programs, preserved films, and other materials from our collection are regularly featured in museums, cultural centers, archives, universities, and festivals worldwide. We have a small research center and a small library, and we also have an online library.

Part of our collection is the papers of Oskar Fischinger and most of his surviving animation process materials. So as Haden mentioned, film preservation and restoration is an ongoing part of our activities. We preserve some of the most famous and significant films in this field of visual music, by Fischinger, Belson, John and James Whitney, Charles Dockum, Harry Smith, Jules Engle, and others. So I do want to mention our new Fischinger book, Oskar Fischinger: Experiments in Cinematic Abstraction. It's available on Amazon worldwide and everywhere now. And I'll read some info from the official blurb: “This new monograph explores the position of Fischinger’s work within the international avant-garde. It examines his animation and painting, his use of music, his experiences in Hollywood, his light colorplay instrument the Lumigraph, visual music theories, and his influence on today's filmmakers and animators. The book contains previously unpublished documents, including texts by Fischinger himself.” I compiled and commissioned the essays, and there's a lot of new research and texts by film curators and historians, scholars, art curators and musicologists,including curators from the Centre Pompidou, Paris, and LACMA, Los Angeles. The book features a new bibliography and filmography, and testimonials by international artists, scholars, historians, and authors. Co-published by Center for Visual Music, distributed by Thames and Hudson.

So I've been using this phrase “visual music,” and Oskar Fischinger has been called the “father of visual music.” But what is this? What is visual music? There's a hundred-year history of visual music on film, and a bibliography stretching back centuries, to Pythagoras and Aristotle. But what is it? There are a number of definitions today, rapidly expanding and changing as the field grows. I'm only going to mention a few. (For further reading of many texts and theories, full definitions, detailed histories, I encourage you to visit our online library, the centerforvisualmusic.org.) Visual music is not synesthesia, that's a buzzword very misused today, particularly misused when applied to Fischinger. Film historian William Moritz wrote in 1986 of, quote: “a music for the eye comparable to the effects of sound for the ear.” He asked us to contemplate, what are the visual equivalents of melody, harmony, rhythm, and counterpoint? He wrote about artists’ desires to create, with colored light and film, a moving abstract image as fluid and harmonic as auditory music. And one more basic definition of visual music: “A time-based visual structure that is similar to the structure of a kind or style of music; a visualization of music, which is the translation of music or sound to a visual language, with the original syntax being emulated in the new visual rendition.” So again, for more theories and definitions, I encourage you to go online, because that's a symposium on the definitions of visual music, that's more than I can discuss right now. So, on to the father of visual music, Oskar Fischinger. Fischinger has also been called the grandfather of music videos, and the great-grandfather of motion graphics. He's the most important and influential filmmaker in this field of visual music. Also very influential in animation, of course. He produced over fifty short films and 800 paintings. His films and paintings are in museums worldwide today. And his films have influenced generations of filmmakers, animators, and artists, continuing to the present day, and you'll find that on YouTube, when you see a thousand films labeled “homage to Fischinger.”

Oskar was born in Gelnhausen, near Frankfurt, in 1900. He studied music, drafting, and organ building, and he was at first an engineer and inventor. He was not a painter until he came to America, later when he was thirty-six years old. So his origins come out of drafting and music. He began his animated film experiments in 1919, first experimenting with wax silhouettes and hand-drawn animation. He invented apparatuses, such as the wax slicing machine, to produce his unique imagery. This was the first of his many inventions, both realized and planned, to achieve his visions. So from the early years, today we're going to see the film experiments known as Spirals and Spiritual Constructions. Wax Experiments is not in this program tonight. It is on the Fischinger DVD, for those that do not have it and are interested in that particular early experiment. I do have some of these, so if anyone is interested, come and find me afterwards. So, from a typescript written by Oskar in 1947, he wrote about his early career. Quote: “Made about three experimental reels of absolute films between 1920 to ‘22, without music, made more experiments in absolute forms and motions. In 1926, walked from Munich to Berlin. Again experimented, showed my films here and there, had my own studio in Friedrichstrasse, made advertising films, got a job with Fritz Lang, making the trick film work in Frau im Mond, and different other films, UFA and others.” Well, we're going to see the film that he made, Walking from Munich-Berlin, where he literally walked, with a 35mm camera, over the course of three weeks. And that is a live-action, single-frame film, in the beginning of the program, I think it’s the third or the fourth film. I'm briefly going to mention here his series of Raumlichtkunst experiments. He mentioned, he made about three experimental reels of absolute films. Well, he used those three reels of absolute films, circa 1926. He used up three to five 35mm projectors, and projected live cinema performances, to music, called Raumlichtkunst. From press reviews and Fischinger's notes, we can understand these shows as attempts to create some of the very first cinematic immersive environments. He used two projectors with colored gels and colored leaders just for the light, for the lighting effects, because back then, of course, he did not have color film stock. He had to hand paint, hand tint, hand tone, for the color, and then use additional colored lighting effects, with two additional projectors. So, some of you may have seen or heard about CVM’s reconstruction of Raumlichtkunst as an HD three-projector museum installation. We showed it at the Whitney Museum for three months, we had a Fischinger exhibition called Raumlichtkunst: (Space Light Art). Tate Modern, for ten months, Palais de Tokyo, and now it's just been installed in Australia. So, but jumping… these were experiments he did circa 1926. So some people theorize that that makes him one of the very first VJs.

So, back to his early chronology. Today we'll see the film record, as I mentioned, of the 1927 journey, Walking from Munich to Berlin. And there's a very nice short statement he wrote about the journey in the Fischinger biography by Moritz called, also called, Optical Poetry, and also on our website, on our Fischinger research site, centerforvisualmusic.org, slash Fischinger. So again, from Oskar’s writing, quote: “In 1928, I saw the possibility to produce absolute films which were perfectly synchronized to music. Records had to be used to run in the theaters. Music became something like an architectural ground plan. Time and rhythm were given, and the mood and feeling in the optical motions...” I'm going to mention here that he had to use records until one could put sound on film, which happened around his Studie Nr. 4. That's a lost film, so the first you'll see is Studie Nr. 5. It's the first sound film that you'll see in tonight's program. Back to his writing, quote: “With the absolute film, music is used to put it over, but the invention of new ways of motion is the main idea, the main force, and the time, or rhythm coordination with music, is secondary, of less importance. People who say these films are illustrations to music are poor in their imagination, like Richter.” (There was no love lost between Hans Richter and Oskar Fischinger.) These absolute films made in Berlin in 1928 to ’32 became his famous series of studies, and made Oskar famous worldwide. The studies were screened in movie theaters worldwide, as the short before first-run features. Some of these early studies, these black-and-white studies synchronized to music, were synchronized to popular music provided by Electrola Records. And there was an ad at the end which said, you can buy this recording at your local record shop, disc number XXX, whatever, making them some of the very first music videos. So tonight, we're going to see Studies 2, 5, 6, 7 and 8. As I mentioned, Studie 8 has Dutch head titles, from a theater which began showing Fischinger’s films back in the late 1920s.

Fischinger was rather busy in Berlin after 1927, after he moved there. He did special effects for feature films in Berlin, for UFA and others, including Fritz Lang. He helped develop a color printing system called Gasparcolor, a three-exposure color printing system, about the same time Technicolor was being invented, but in some ways a precursor. He began making color films circa 1933. He made a very famous series of Ornament Sound Experiments, exploring synthetic soundtracks. He also made advertising films, most famously for Muratti cigarettes. Oskar’s films, especially the color films, then his Muratti ad, drew attention from Hollywood, from Paramount Studios, where Ernst Lubitsch hired him and helped him immigrate to Hollywood in 1936. Composition in Blue, which we'll see tonight, was the last film he made in Germany. Though he was lucky to have escaped Nazi Germany, his career would greatly suffer in Hollywood. Regarding the famous color Muratti ad, the print you're going to see here tonight is only a bump-up from a 16mm print. That is the only case tonight where a print has not been restored from the 35mm. This film has not yet been properly preserved from the nitrate. We do have 35mm nitrate originals, but it's scheduled to be done soon, pending completion of funding.

Fischinger came to LA in ’36, becoming the direct link from the European avant-garde community to West Coast experimental filmmaking. In Hollywood, he briefly worked at Paramount, Disney—very unsuccessful experience on Fantasia—MGM, and for Orson Welles.... I think I'm getting the signal to, is that the signal? Okay. Just checking!... Paramount experiment, experience was not successful. You're gonna see two versions of a film, one with a head title Radio Dynamics, and then the next, Allegretto. This was a film he started at Paramount but could not print in color, took the name Radio Dynamics off of it, finished it later, in 1943, under the name Allegretto, one of the most famous visual music and abstract animation pieces that exist. In America, Fischinger did get some support from the Guggenheim, from Hilla Rebay, to make a few films. We'll see a few of those tonight. We'll see An American March and Motion Painting. Motion Painting, unfortunately, was the last film that he did receive funding for. It was very difficult for him in Hollywood, with his lack of command of the English language, at first. He was also an enemy alien during the war years. He struggled and just did not find very much work or support at all. Luckily, the Guggenheim stepped in, so he was able to make a few films. So his relationship with Rebay ended after Motion Painting, in 1947. He never again found support to make another of his films. He made a few advertising films in the 1950s, but other than that, he spent the last twenty years of his life painting, planning films, drawing many, many animation tests and sketches, which were never completed or filmed. He could never find the money to film them. We do have a lot of these in our archive. That's another problem, another problem project. Project Unshot Fischinger! A huge amount of animation drawings, tests, scraps, bits and pieces. He also, in the last twenty years, made stereo paintings, a 3D film test, and planned a series of motion painting films. He continued his experiments with synthetic sound. And in the new book, you can see some images of this unshot work, the work during the last twenty years of his life, the unshot and the unfilmed work.

So, for more about Fischinger, for more about our activities and programs, please visit our website and our events page, and the official Fischinger research pages, centerforvisualmusic.org. And now let's see some of his completed films. So enjoy the show, and I guess we're going to have a brief Q&A afterwards. Thank you.

[APPLAUSE]

John Quackenbush 18:36

And now the Q&A, with Haden Guest and Cindy Keefer.

Cindy Keefer 18:51

Just a few comments before we have questions. The last film was rightfully considered Fischinger’s masterpiece. It was his last completed film. We do have small tests, and we do have typescripts, where he talked about wanting to make a series of motion paintings. So we have small bits, small fragments of what Moritz called Motion Painting 2 and 3, which are stunning, but they are just small fragments. But had he found support in Hollywood, we might have had a series of these films, of the last film. And the other thing I wanted to mention is Fischinger as a child grew up in the German village of Gelnhausen, and his family owned a brewery, which will explain the inspiration for the third film, of the drunks.

Do we have any questions? Over here?

Audience 1 19:42

Did he work by himself? Or did he use assistants to make these pieces?

Cindy Keefer 19:49

Mostly alone, except for a series of the black-and-white studies. He was quite successful in Berlin. There was a lot of orders and commissions for some of the black-and-white studies. So he had assistants on, I believe, six through eleven-ish, about five or six of the studies there. Other than that, he generally worked alone.

Audience 1 20:10

So, you know, I've pretty much figured out how he did something like Composition in Blue. Do you know how long it took them to do a piece like that? Because it's obviously so frame-by-frame, time-intensive to do what he did.

Cindy Keefer 20:24

That one we don't know exactly, because he was working on that in the evening, in secret, so the workers in the studio during the day didn't see it. So there was commercial work, and studies being done up in the studio during the day. So he kind of worked on that secretly, at night. We don't have an actual record. We do know that the last film, Motion Painting, took nine months.

There was the guy next to you, I think, rose his hand? That, yeah.

Audience 2 20:55

[INAUDIBLE] astonishing to think that this person managed to do this, figure out the picture frame, and how to use it so incredibly, completely. [INAUDIBLE] time before computers and before all the digital assistance that we have these days. Can you comment on how he did something like Study Nr. 7? I mean, did he actually have multiple pieces of charcoal that he just scratched together on the paper, and then photographed each of those sheets of paper?

Cindy Keefer 21:25

Yes, that's thousands of sheets of paper, each one of those studies. One of those, I believe we have a record, I could be wrong, but I think it's like 4500-ish sheets for one of those studies. That that was charcoal on white paper, and then flipped to reverse. And we do have many of these. Luckily, that was acid-free paper the Germans used, luckily. So we do have a number of original drawings, especially from Study Nr. 8. But one thing also to remember is, as remarkable as it is, remember that this is not just the beginnings of abstract animation, when Fischinger started. This is the beginnings of animation, as well. And a lot of these early films were just, really experimenting with animation, which happened to be abstract, which is what he chose to work in.

There was someone over here?

Audience 3 22:21

Alexander Alexeieff and Claire Parker made a commercial film with stop-motion cigarettes. I don't remember the year, but it's around the same time as Muratti Marches On.

Cindy Keefer

It's after.

Audience 3

Ah. So, presumably they saw this, and someone said, “do that, make a film just like that”? Or were they friends, or…?

Cindy Keefer 22:41

They weren't friends, but afterwards, I don't know how long afterwards, Alexeieff was quite proud of it, and somehow said to Fischinger, wrote to Fischinger, or something, how it was their homage, but Fischinger really kind of considered it a rip-off. I mean, he didn't really like homages. He wondered why people weren't doing their own creative work. Several people did cigarette commercials. Hans Fischerkoesen has a dancing cigarette commercial as well. So, it was quite influential. It was shown everywhere. It was shown in first-run movie theaters. I mean every, the entire world saw that, I mean, the motion picture-going world, saw that, and there was a number of rip-offs, or homages.

Audience 4 23:28

Do you know how he would time shapes and colors to the various songs? Would he do something like, this part this to part is three seconds, so I need this many frames? I'm just wondering how much of that...

Cindy Keefer 23:48

Yes. Yes, he would pre-plan. In fact, in the book you can see a couple examples. He would take music if he could, for some of them, he could get the score, the record, the sheet music at the local record store. And he would notate, very carefully, the dynamics of the motion on that. For others, where he did not, where it wasn't available, he would hang graph paper on the wall, he would listen to it, and he would chart out the music, write it out and plan along the animation to it. Then there was another method in which, early on, he would take a record player which he had modified to stop and start, and he could measure exactly a section of music, and time it out, and then plan his animation to it. It was all very carefully pre-planned. Except, probably the least pre-planned, in a way, was the last one, which was a painting, that was a painting, every single brushstroke equals an exposure of the camera shutter. So while that was planned in general, it wasn't planned down to the tiny movement as much as some of the others were.

Audience 5 24:57

I see the painting, and the drafting background, but where did he get the musicality? [INAUDIBLE]

Cindy Keefer 25:04

He studied violin, and he also, for a brief time, apprenticed to an organ builder. So this is what you get when you cross engineering, drafting, and music. And a love of abstraction.

Audience 6 25:19

But you said he had a lot of, or you have a lot of his artwork from films that weren't made? Has there been any interest from people who want to, like, finish a film, or make a film from the artwork you have?

Cindy Keefer 25:35

I think the Fischinger Trust is not really interested in that, in finishing the film. And you can't really “finish,” I mean, ’cause the film isn't started enough to finish. It's not like it's halfway done, or three-quarters done. It's little, a stack of drawings, like this. I mean, less than, a couple seconds, maybe. Maybe five seconds, some of them. I mean, just the very initial ideas. We are fundraising to shoot all of these, and put them all on film, and then digitize. This is a long, tedious process, both the fundraising and the shooting. Some of them are nitrate cels that he did paint, we have a series of a few hundred nitrate cels, for example, which are very difficult to shoot, since everything has gone digital. But I think that the Fischinger Trust is not interested in having anybody, like, finish Oskar’s films, in the same way that Oskar wasn't interested in homages. But we're interested in showing what Oskar wanted to do, but there's not enough there, really, to make a film from it. I hope that answers the question.

Audience 6 26:32

Yes. And also, The Sorcerer's Apprentice, any connection with Disney, or…?

Cindy Keefer 26:38

Oh, there's a very nasty connection with Disney. Fischinger had this idea to do a concert feature, set to classical music, and proposed, you know, the conductor standing there in the very, very beginning frames, and you see the conductor from the back. This idea kind of became Fantasia, and without very much involvement from Fischinger. And it's a very long story. There's an article on our online library, called “Oskar at Disney,” “Fischinger at Disney, or Oskar in the Mousetrap.” It's a long piece by William Moritz about all the nastiness that happened. Basically, Fischinger brought the idea to the composer Stokowski, they were supposed to do it together, Stokowski stabbed him in the back, took it, got hired on Disney, became the collaborator, etc, etc. Oskar got a menial, small job, where he did some designs, and then later he quit. But during the time he was at Disney, a very unhappy, a very terrible time for him, they did screen Fischinger’s films regularly for the Disney animators, to teach them how to animate to music.

In the white shirt again.

Audience 5 27:46

Yeah.

Cindy Keefer

I think you, the mic?

Audience 5 27:48

[INAUDIBLE] body of work all at once, and realize just how much of his stuff did end up in the Toccata and Fugue and Fantasia. And even, you know, the gesture of the conductor at the end of that, the thing,

Cindy Keefer

Absolutely.

Audience 5

the great arches flying off into the sky.

Cindy Keefer

Absolutely.

Audience 5

It’s all Oskar’s stuff.

Cindy Keefer 28:05

It really is. There isn't any of his actual designs in this work, but the influence is all over. It is all over, and all throughout Fantasia, through all of it, not just the box segment. All over. And by the way, there is a lot more of Fischinger’s film. These we consider the popular classics. There's approximately fifty films. There's fifty if you count, like, a couple home movie kind of things that he made. So there's quite a lot more film, there's more studies, there's approximately, I think, it's like fourteen studies, though one wasn't actually filmed. There's more advertisements. And there's more, there's more color, and more black-and-white films, there’s a lot more early tests, too. So we count about fifty. We do have a Part Two of this program that's the more obscure rarities, so maybe sometime we'll bring that one back.

Haden Guest 28:57

I think we have time for one more question.

Audience 8 29:01

You had said toward the end of his career, that he was involved in painting and stereo images?

Did he do any stereo animation?

Cindy Keefer 29:09

He did a test. He had no money then, he was very poor and he had, what is it, five children? So he only, on his own, was able– he did like a thirty-second test, which we do have. We have screened it at 3D festivals. It's absolutely spectacular. But as far as at the end of his life being involved in painting, he actually started painting in 1936, when he came to America, so he painted from ’36 to ’67. That's why there's 800 paintings, 800 paintings and drawings. That does not count animation drawings that were used in the making of the film. That's entirely separate pieces of artwork in their own right, individual paintings, which are in many collections, but I think the closest one to here, probably, is New Haven. The Yale Art Gallery, has one. and the Guggenheim has some very nice ones, which they never show.

Haden Guest 30:01

Please join me in thanking Cindy Keefer.

Cindy Keefer

Thank you all.

[APPLAUSE]

© Harvard Film Archive