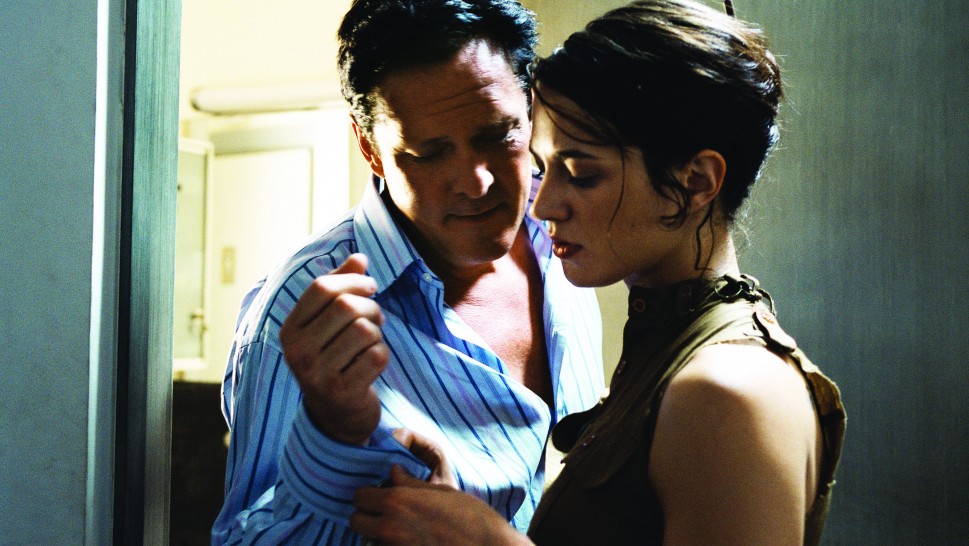

In the vein of icy thriller demonlover, Boarding Gate is a mix of Hong Kong funk and Eurocool. "It" girl of the hipster set Asia Argento stars as a young woman working as a drug runner for her Hong Kong boyfriend (Ng), whose life gets even more complicated when her sleazy ex (Madsen) reappears. Bouncing between Paris and HK, the film reveals itself to be a deliberately feisty nose-thumbing at the new global marketplace (including, as Assayas notes, "the new order of film finance").

Audio transcription

HADEN GUEST 0:00

Ladies and gentlemen, good evening and welcome to the Harvard Film Archive. My name is Haden Guest. I'm the HFA Director. I’d like to thank you all for coming tonight. A very special occasion, we have with us tonight Mr. Olivier Assayas, a visit we've been eagerly anticipating for quite some time. Olivier Assayas, as you know, has been one of the most beloved and celebrated directors working in France for over 20 years now. As the very strong attendance throughout this weekend and tonight demonstrates, his films, are of course of great interest to American audiences as well.

Assayas first made a name for himself as a film critic writing, of course, for Cahiers du cinema. And it was there that he quickly proved himself to be one of our perceptive critics writing on the cinema and Asian cinema, in particular. In 1984, he co-edited a special double issue on Hong Kong cinema, which to this day, really stands as just a remarkable work of scholarship, not only for its discussions of individual auteur directors but also its examination of a popular genre films and of the sort of the industrial apparatus itself. So, definitely hunt this issue out if you can. Assayas was also, it should be noted, among the first critics to draw attention to the work of major Asian directors who were relatively unknown in the west at that time. Hou Hsiao-hsien and the late and very great Edward Yang are just two of the names that immediately come to mind. In this month's issue of Film Comment is a really excellent translation of a wonderful article that Olivier wrote in tribute to Edward Yang. So, definitely take a look at this if you have any interest at all in one of the greatest directors that has come out of Taiwan.

Now, Olivier Assayas as a filmmaker distinguished himself with a group of early works such as L’Enfant d’hiver and L’eau froide, which we showed on Saturday night, and which is one of Assayas’ real masterpieces. It was this group of films that offered incredibly intimate portraits of complex, ever-changing human relationships, usually focused on very young characters gripped by difficult life decisions. L’eau froide certainly stands as one of the great achievements of French cinema in the 1990s, I would say. It's a powerful invocation of the struggles of disaffected youth that easily ranks up there with the work of Nicholas Ray. Another milestone is marked by Assayas’ breakthrough hit Irma Vep, with which he boldly entered into very new territory, embracing larger, more abstract themes here, about film and film history, about global capitalism, a theme which we'll see tonight continues to resonate throughout his work. And anchored in these really marvelously choreographed portraits of people falling in and out of love and I use "choreographed" in both the literal and the metaphoric sense; the camera movement in Assayas’ film is really astonishing. And he's able to.... this idea of structured improvisation that was so important to the French New Wave. So, a different variation of that approach is found in the work of Assayas. Now, since Irma Vep, which was 1996, Assayas has really kept us all guessing as to what each of his next projects is going to be. And this is giving way to a series of wonderful, unpredictable and unexpected projects. Projects often taken on, it should be noted, with great risk, a risk which I think ultimately pays off with extremely satisfying accomplished films. These have ranged from his gorgeous costume epic, Les Destinees sentimentales, we screened here on Sunday, and to the fabulous Demonlover, which is of course is a thriller that captures the dark libido of global capitalism better than just about any film I can think of. And the surprises continue to tonight's film Boarding Gate, which returns to the same general territory of Demonlover, but I think with striking, utterly different results. For those of you who know and love Olivier Assayas' work, I know you're as eager as I am to hear him talk about tonight's film.

But before I welcome Olivier to the podium, I just want to thank a few individuals and institutions who made this evening and this retrospective possible. And first and foremost is French Cultural Services. We have the great pleasure of working with many different cultural departments, from nations around the world, but none quite works with such professionalism and panache as the French and so, I'd like to thank in particular Brigitte Bouvier and Mr. Francois Gautier.

[APPLAUSE]

I'd also like to thank Richard Schakanski at Yale University who really planted the seed that started this project, as well as NYU. So, with no further ado, I'd like to welcome Olivier Assayas. And we will be returning for Q&A and discussion of the film after the film is over. Thanks.

OLIVIER ASSAYAS 5:54

Thank you very much. It's a great honor to be here and to introduce this film. I wish I could have stayed longer. It's going to be a very short stay, but I know it's going to be extremely frustrating for me. This, the film you are going to see is– It’s always very difficult to introduce pictures, because you don’t want to give away this or that. And also I think that for me, my movies make sense. I mean, I kind of try to understand what has been going on once they’ve finished, once I'm starting to introduce them and discuss them. When I am making them and when I'm planning them it’s, you know, sometimes it feels weird to me, this and that, it just feels obvious. I've never made a movie that did not feel absolutely obvious at that specific moment, like you know the only thing I could have done.

In the case of Boarding Gate, I think in the end—it's the last installment in the trilogy, which I started unknowingly when I made Demonlover. I think that Demonlover and Clean, the movie I made after that with Maggie Cheung and Boarding Gate are three movies that where I try to use the globalized texture of modern cinema. I think I've been trying to move out of whatever I have been doing within the system, within the logic, within the scope of French filmmaking and see what happens if I use ingredients from other cultures, if I use ingredients from different literatures, if I use different images. If I stopped making chemical experiments and just doing things people usually don't do and not only do they not do them but they think it's wrong to make them. They usually think it's wrong to try and potentially it can be wrong to try, but still you don't know until you have the result. And so in the case of Boarding Gate, I think I've had for ages this dream of making a movie in Hong Kong. Hong Kong has been an extremely important part of my life for many reasons. It's where I discovered Asia, that's where I spent time in the early 80s, in 1984 actually working on the history of genre filmmaking there. It's where I met filmmakers who have been such a powerful inspiration for me again, Hou Hsiao-hsien, Edward Yang, the Taiwanese New Wave. The model Asian film culture stayed with me as maybe a different culture I belong to, maybe in the deepest sense, than I belong to the French modern tradition, but then you know, I don't live in Hong Kong. Even if I spent time there and it's... Stories just don't come that easily, you don’t just press a button and so I felt that the dream to make a movie in Hong Kong will never, ultimately be accomplished. And then this movie came up all of a sudden, because it's based on something similar to this kind of happened and which didn’t, it was not exactly, exactly Hong Kong but it was part Paris, part Geneva actually, and in part Asia, but the connection between the East and the West worked in an interesting way for me.

So I had met Asia Argento, which is the second extremely important reason why I made this film. I had met her and I sensed when I met her that I met maybe the ideal actress for some of the things I had been looking for in my films. You know, I think this is something we have to discuss after you have seen the film. When I met her, the way we connected, what I felt for her relationship to cinema indicated that all of a sudden I had in front of me, someone who was just speaking exactly the same language, who understood everything I was saying and who again, had this incredibly modern relationship to cross-cultural themes and who was halfway between modern international genre cinema, Italian cinema, European cinema, and I felt that I should not miss the opportunity of making this film with her, with Hong Kong, and just having a shot at making a genre film. It's not exactly a genre firm, but I think it’s the closest that I'll ever get to making something that's like a genre film. And it's really something that has been in the back of my mind, I've been toying with the idea of putting bits and pieces here and there, and I feel I wanted once to go all the way. So sorry for being extremely long. Hopefully everything, all this mishmash will make sense once you’ve seen the film. And I will be extremely happy to discuss it with you after. Thank you.

[APPLAUSE]

HADEN GUEST 12:24

We’re actually going to start with a trailer for Arthur Penn’s Micky One; this is a flat trailer, it is not in scope, but we're not adjusting the masking for that. Okay, and that's a film that plays next Saturday with legendary American director Arthur Penn in person. Thank you.

[APPLAUSE]

-----------------------------------------------------

HADEN GUEST 12:46

Maybe I’ll just open– [ELECTRIC, ZAPPING SOUND] Electricity. I would like to break the ice with a question to you Olivier, and I want to ask you about [something] expanded from our conversation before. But one of the central themes of Boarding Gate is one that actually recurs throughout your work— Demonlover, of course, but I think you know, earlier Irma Vep and even Le destinees sentimentales—has to do with this fascination with "big business," shall we say, you know, global capitalism and looking at the way in which this theme has evolved in your work. In Le Destinees sentimentales, you're dealing with an international company, the porcelain factory, and you see the way in which this environment affects the individuals and their relationship. And then move through Demonlover to here where we have this, let’s say, slightly unusual relationship, a psychosexual relationship between this couple that mirrors in a maybe distorting, maybe in an accurate way, this dark economy in which these businesses flourish.

OLIVIER ASSAYAS 14:06

Okay, it's not easy. Well, just to try to answer the question, yes, I've made Le Destinees sentimentales which was about the story of how at the turn of the 19th century, of course, local businesses, craftsmanship had to deal with the internationalization of commerce. All of a sudden, just business at a local level had to open up because they had to deal with the foreign concurrence and blah, blah, blah, and it just kind of changed the relationship between workers, the owners and blah, blah, blah. And, of course, it was the beginning of modern capitalism. And after I had made this film, I made Demonlover which had tried to deal with something similar but happening now, the way of course we recognize the [UNKNOWN] and classic categories of how class struggle defines work relationship within the [UNKNOWN] has completely changed because it's just the world has changed, circulation of money has changed. We live in a society that’s completely different and I just felt it was changing in many ways, going in different directions, and I tried to capture it when I was making Demonlover. But Demonlover was a much more abstract movie than Boarding Gate. Boarding Gate to me is a much more simple movie in many ways, and it just uses that situation as a background. It just tries to use the story that ultimately is the story of a woman, of a man and woman, specifically the story of this woman. It just tried to give a credible, believable background within the world of modern finance. But it's ultimately not so much a statement. It's just an observation.

HADEN GUEST 16:37

Questions...for Olivier Assayas? From the audience? We’re still processing this film.

AUDIENCE 16:46

[INAUDIBLE]

OLIVIER ASSAYAS 16:51

Asia.

AUDIENCE 16:54

[INAUDIBLE]

OLIVIER ASSAYAS 17:00

I think that it's a part that involved both moments which were intimate, which had to deal with inner emotions that were very low key and subtle, etc. And also running around with a gun. It's something that I feel I would not have written that part for a French actress, or any of the actors I've worked with now because I think they would have felt weird on one side or the other. And what was very specific with Asia is that she had this kind of physical energy. Because she's the daughter of this great filmmaker Dario Argento who makes those great horror movies, she's not afraid of just going all the way into ground that most other actresses would consider dangerous or weird or whatever. So,I think it's meeting her, speaking with her that kind of gave me the confidence to try and go for a movie that would use both sides of what I sense with her. So in that sense the movie owes a lot to her. I think it would not have happened without her in many ways.

AUDIENCE 18:34

I was curious how you cast [INAUDIBLE].

OLIVIER ASSAYAS 18:39

Yeah, the film is opening soon. I'm not sure when but I would like in a few weeks. Magnolia is distributing.

AUDIENCE 2 18:52

[INAUDIBLE]

OLIVIER ASSAYAS 18:54

Kim Gordon? Well, I’ve known her for awhile, I'm a big fan. We met because I used a Sonic Youth song in Irma Vep, so whenever there was the American opening of Irma Vep, there was a party or a premiere or whatever, she showed up with Thurston. And, you know, they were happy with the film. So I was just impressed—and this was like 10 years ago—and we’ve kept in touch. We've kept in touch ever since. Sonic Youth made the score for one of my films, for Demonlover, and I also then invited them to a rock concert in France, which I filmed. It's a movie which is called Noise, it's this kind of an experimental music movie, but I filmed her with Thurston when they were doing this side project called Mirror Dash. And basically we've been friends and working together for awhile and somehow I’ve always known that she wants to act. I mean, she wants very much to act, I think she likes to act. And when I told her about this film and if we're going to shoot in Hong Kong, and she said, “Oh, you know, I grew up there. I spent so many years when my father was working.” I'm not sure what he was doing. But she spent time in Hong Kong as a teenager. And I said, “Oh, okay, so maybe there was a way to connect you to this story.” You know, I think it was fun for her. I think it was fun for me and you know, we enjoyed it. But we were shooting in that warehouse in Hong Kong, which was like 100 degrees and it was one of the old warehouses for the old Hong Kong airport which they closed down ages ago and it was just horribly hot and disgusting, and basically a mess with all those Hong Kong actors running around with guns, etc. and she just she came back from some kind of show they had in Australia, just stopped on her way back and I think she just had trouble adjusting, but had fun.

AUDIENCE 21:38

[INAUDIBLE]

HADEN GUEST 21:43

Yes, the question was asking about the colors and lighting in the film.

OLIVIER ASSAYAS 21:52

This film was shot like in six weeks, meaning 30 days I think or maybe 31 days maximum—meaning it was shot like really fast. I worked with Yorick Le Saux; it was the first time we worked together. I've known him for a long time because he was doing second camera on a couple of my films and he shot also the making of Demonlover, I think. He's an excellent cameraman. He's just so instinctive etc, and we improvised a lot, meaning that we had very little time to light; we used very, very, very little light in this film. Yes, so it was extremely simple and so I suppose that a lot of what we did was done in the lab. The film was shot in Super 35 using three-perf, meaning it was all shot with– Okay, "three-perf" means you print instead of having a big inter-image—basically [LAUGHS] I'm trying not to be too technical here! The normal movie image is four perfs. As you notice, CinemaScope is pretty wide. So four perfs is a square, so within that square, you have a long rectangle in the middle and a lot of black between the rectangles. So what we’re doing is instead of having– You know, film is 24 frames a second… And so we reduce the inter-image, we shoot inside the inter-image... Okay, it all boils down to the fact that the film is slower within [UNKNOWN] so the camera is less noisy, so you can use the small Aaton camera which is basically very noisy. You normally don't use that camera to shoot with direct sound. But with this method—which makes the camera less noisy—you can use this very light camera which is very similar ultimately to a DV camera. I mean in terms of its weight and shape, so the cameraman can eventually shoot all day handheld and not break his back. So that's what we privileged in this film, making long takes handheld, specifically in the Hong Kong part. Because ultimately the film is shot in different styles—like the Paris scenes in the flat, it's on a dolly. It's more choreographed, etc. Hong Kong is ... almost everything is handheld. But the idea was to be able to shoot in the street or Hong Kong or to shoot in a warehouse or wherever in Hong Kong, documentary style. We had a very small crew which was also the reason why we could shoot fast. Okay, so I'm just going all over the place but I don’t know if I’m answering your question. [LAUGHS]

AUDIENCE 25:43

[INAUDIBLE]

OLIVIER ASSAYAS 25:49

Oh, you mean because in terms–?

AUDIENCE 25:52

[INAUDIBLE]

OLIVIER ASSAYAS 26:04

Yes, yes, true.

AUDIENCE 26:06

[INAUDIBLE]

OLIVIER ASSAYAS 26:11

Well, it’s a–

HADEN GUEST 26:14

Did everybody hear that? Okay. The question wasa rather interesting one. The gentleman's interested in what he said is not there: children, food, space between things. And..

OLIVIER ASSAYAS 26:30

Oh, ok, so I got you wrong obviously. So well, there's a lot of things that are not there. [LAUGHTER] So, we shot a lot of the film with long lenses. So I suppose it uses a certain level of abstraction. Meaning of course when you're using long lenses, you have less background, background is less precise. There's something oppressive about it, which is obviously what I was looking for. And also the film happens like in three days. And it's one character that we're following non-stop, and we’re kind of glued to her. So I suppose that she's on the run, and there's few children around. And [LAUGHS] there’s food in the restaurant at some point. [LAUGHTER] She just runs through the restaurant and people are eating.

AUDIENCE 27:45

[INAUDIBLE]

OLIVIER ASSAYAS 27:48

Yeah, yeah, it's true. It's true.

AUDIENCE 27:53

[INAUDIBLE]

OLIVIER ASSAYAS 27:58

Well, it's as old as the movies, I suppose. It's the connection between different desires and different ideas. But what clicked is the story I read in the newspaper. Just to sum it up, the story was about this banker who was like big time. Who was found shot dead in his flat in Geneva and he was handcuffed and he was in this kind of transparent latex suit and obviously, you know, he had been shot in the middle of some kind of, you know, sexual game. And the girlfriend with who he has had this kind of on and off affair for ages had ran away and she went to Sydney in Australia and she locked herself up in a hotel room and she freaked out and took the plane back and was arrested. And to this day it's not clear if she killed him. Because it has not been on trial yet. People don't know if she killed him because their affair was like going nowhere obviously, or if it was some kind of contract and she was paid. In newspapers people were discussing what this or that, one or the other and when I was reading it I thought maybe it's both. Maybe it's both things at the same time. And also when I read the story I felt it was like out of Demonlover, and Demonlover to me was like some kind of abstract movie about ideas, and all of a sudden I had some kind of real life situation, with real life flesh and blood people who went through a story that was so similar to something that I had fantasized. I thought it was interesting to look into it. And it gave me an opportunity again to go to Hong Kong, to shoot, to film Hong Kong and to make a film with Asia.

AUDIENCE 30:21

[INAUDIBLE]

OLIVIER ASSAYAS 30:26

I wrote the script pretty fast, like a couple of months after it happened. I was even in trouble. It was not big trouble. But when the film was released in Switzerland, all of a sudden they were talking about lawsuits, etc, etc. Because it kind of dealt with something kind of sensitive, but then they dropped it and I never heard of it again.

AUDIENCE 30:57

[INAUDIBLE]

OLIVIER ASSAYAS 31:07

So, I’m not…

AUDIENCE 31:08

[INAUDIBLE]

OLIVIER ASSAYAS 31:20

Yeah, again because it was obviously sensitive and it's about real life people etc. So I just used it as a starting point and then I moved away from it, I mean it's just I think I used what I needed in the story to get me moving and once I got moving it became a story on its own and the characters are very different from the real life characters, so after that has been the basic process of fiction.

AUDIENCE 32:03

[INAUDIBLE]

OLIVIER ASSAYAS 32:14

[LAUGHS] Yeah, it's very difficult to answer that question. Okay, yes, there's some kind of model. There’s some kind of model. I’ve known someone like that.

[LAUGHTER]

AUDIENCE 32:34

[INAUDIBLE]

OLIVIER ASSAYAS 32:40

Yeah. The end of the movie. I was not happy with the ending of the movie I wrote. I wrote a different ending. And from the start, I knew it was just like, blame and it did not work. But I had no idea how the movie should end. And one day we were shooting this scene in the parking lot of this hotel. And I remember shooting the scene, all of a sudden I realized that shot had to be the ending of the film. So I changed it, I made it much longer than whatever I had imagined. And it's just something I had in the back of my mind. So it was like "let's try a day which is much longer and let's do this and let's do that etc, etc." And I realized that Asia, at that moment understood that we had found the ending of the film. So it will be really without any communication between us, but we made the shot which obviously was the ending of the film, which was an open ending, which somehow to me kind of made sense of the whole story. But until we came to that point in the film I was very scared. I had in the back of my mind that at some point I would come up with an idea of it, but we're approaching the end of the shoot, I'm just like nothing was happening so … [LAUGHS]

AUDIENCE 34:45

[INAUDIBLE] So specifically, we can be set in Paris, in Hong Kong. [INAUDIBLE]

OLIVIER ASSAYAS 35:19

Yeah, to me Paris is not exactly Paris. We never mentioned Paris. And I think there's no scene in Paris. It's all shot in the suburbs, in offices that could be like anywhere in the world. So basically to me it was more like some kind of, some shape, chamber you say "chamber pieces"? [UNKNOWN] Musique de chambres? It's more like, I have this notion that the first half of the firm was in this very claustrophobic, modern, Western world, abstract modern Western world, and once the character just escapes from it, she gets into wherever history's happening. Where somehow there is some kind of lively energy at the street level and all of a sudden she's in the middle of that and it kind of revives her. I mean, I'm putting it in very rough terms, but basically that's what I had in the back of my mind. The first half of the film to me, it could have happened in London, it could have happened in Vancouver, in New York, wherever. To me it's generic. I wanted to keep the feeling of a generic Western town. Whereas in Hong Kong I wanted to be very much in Hong Kong.

AUDIENCE 37:18

[INAUDIBLE]

OLIVIER ASSAYAS 37:20

Well, the unexpected part in Hong Kong had to do with working with the Hong Kong crew. Because I had been on Hong Kong film sets and I knew that there was the same kind of energy as on French shoots and maybe even more so because just in Hong Kong because just people shoot so fast. It's so energetic. But the one thing I had not anticipated is that there's so many people on Hong Kong sets because labor is so cheap. All of a sudden when you need like one person, you have ten, like when I asked to move the camera from here to there, you'd have never less than six people around the camera and I said “just please can we just have like two people around the camera?” It was impossible. We had to invent stratagems to get rid of part of the crowd, of all that crowd. So we would set up a shot there, so I would send my assistant, we would use part of the crowd, and then the cameraman would rush somewhere else [LAUGHS] and shoot, because a lot of this stuff is shot with hidden camera, like when Asia goes in the metro, in the underground at some point. Of course we had no authorization and basically we have the camera in a bag, we came first there "okay, so you go there, you go here, you take off your shirt, you put it there in the dustbin and then you move on." And so we came back and we just got the camera out of the bags, said “Asia come on, do it!,” we shot it and we rushed out before they sent the cops! [LAUGHTER]

AUDIENCE 39:36

[INAUDIBLE] Do you feel that…[INAUDIBLE]...have any weight or moral consciousness, terrible act...[INAUDIBLE]...second half of the movie…[INAUDIBLE].

OLIVIER ASSAYAS 39:56

Yeah, yeah, I know. [LAUGHS] Ultimately, the only answer I can give you is that the moral weight of the murder comes before the murder. Like, you know, she came to kill him, but then she does not want to kill him and then she wants to kill him again and then she decides that she wants to spare him and then he locks her into the flat and all of a sudden she has to do it. To me the whole scene, the whole movement is about her not being able to make a decision, to make up her mind because she doesn't want to kill them because she loves him, because she's scared, because whatever. And then it's just so overwhelming. And she's just on the run.

I remember when we were on the set, Michael Madsen told me, “Oh, but you know you should not kill poor Miles. [LAUGHTER] The audience will be angry with you because you kill Miles.” And I said, “Yeah, you’re right.” But then I felt that there was some kind of poetic or abstract logic to the whole story. I mean to me, yes, she's killing him, but basically, she's killing her past. She's killing whatever is dragging her back. She's getting rid of Europe, she's getting rid of whatever is trapping her into a situation she has created, she's partially responsible for, but also which is basically suffocating her. And all of a sudden when she runs away, she breathes again. She starts to become herself again, she becomes alive again, even if it's in the middle of this crazy mess and yes, we kind of root for her because we think that she's got rid of her past and she's trying to become a new person. But we don't know how it will all turn out in the end, right?

AUDIENCE 42:38

[INAUDIBLE]

OLIVIER ASSAYAS 42:52

Yes, yes.

AUDIENCE 42:54

[INAUDIBLE]

OLIVIER ASSAYAS 42:59

Yes.

AUDIENCE 43:01

[INAUDIBLE]

OLIVIER ASSAYAS 43:05

Oh, yes, of course. Of course. No, I think she was in love with Lester. She was in love with Lester. She's been in love with Miles. I mean she has been a victim in many ways. She shows that she has trusted Miles. She thought the relationship would lead her somewhere. And then she realized it's leading her nowhere. And she's instrumentalized by Lester, who ultimately loves her, but in his own way. But I think that at some point, she realized that she's been betrayed by him. And, of course, at that moment, there's not much meaning to whatever she has done and she has very little hope left for any kind of future and so gradually she kind of picks herself up and...

AUDIENCE 44:11

[INAUDIBLE]

OLIVIER ASSAYAS 44:20

Yeah.

AUDIENCE 44:21

[INAUDIBLE]

OLIVIER ASSAYAS 44:36

And, yeah, I think in the scene with her, she always has in mind that she has a choice. She always has a choice, at some point she doesn't have a choice anymore because gradually that degenerates but for a long time she does have a choice and it's all going back and forth. They’ve broken up, they've broken up a few times she says. But I think they've broken up and that time they have broken up for good before the film starts, and she comes back to him. She comes back to him and she does not know she will be attracted to him again, in a way. I think she comes back to him. You know, it's what I had in the back of my mind when I was writing—maybe that’s not what Asia had in mind—but what I had in the back of my mind, she was coming back to kill him. And then she just remembered that she had loved him and she remembered that there was something between them and kind of got herself ...

AUDIENCE 46:02

[INAUDIBLE]

OLIVIER ASSAYAS 46:03

Well, I leave space to the actors as much as I can. So, specifically in this kind of situation where obviously everything is about ambiguities and tiny fails, which can just drag things in this or that direction, I would never say to an actor, “This is what this shot means. This is what your character thinks.” We discuss the character in the beginning. Once we have discussed the outline, I trust the actors to have– It's like putting the process into motion, and then being somehow a spectator of that process. If something just goes completely in the wrong direction, I would say it, and also when we are on the set, I shoot different versions of every shot,. I mean, it's not like we do like five, six, seven, eight takes until we get the right take. Hopefully we get five, six or seven right takes. Except they are all different. They have all tiny, different nuances. We try this, we try that, so when I'm editing, I just can somehow also reconstruct what makes the most sense to me. What looks the most right.

AUDIENCE 47:33

[INAUDIBLE]

OLIVIER ASSAYAS 48:11

Yes, yes, that's true of course.

AUDIENCE 48:13

[INAUDIBLE]

OLIVIER ASSAYAS 48:28

Well, the question of the language is mostly about Asia because I don't think Michael speaks any other language. Asia is totally fluent in French, Italian, English; she acts in the three languages. My experience is that she's happier acting in English. She feels more like herself when she's acting in English. It's extremely basic. Because I speak the three languages, I speak Italian, I speak English and I speak French; and I speak English with Asia and it's just completely natural. We never speak Italian, we hardly speak French—at least when we speak French it feels awkward—so it was like that before we started shooting the film.

AUDIENCE 49:49

[INAUDIBLE]

OLIVIER ASSYAS 49:51

No, I wrote it in French, because I always write in French. I get it translated. Then I change the translation, and then we improvise on set. [LAUGHS] Well, we adapt the writing, to put it that way. So, in that case, well, I knew the movie would be in English but ultimately English is something that just comes more naturally to Asia.

And in terms of La Moustache, I'm not sure I will give you a satisfying answer. Emmanuel Carrère, the director of La Moustache, is an old friend. I like him very much. I think he's a great writer. And he made a brilliant film called Retour a Kotelnitch, which is a documentary, incredibly underrated, brilliant movie. But La Moustache I didn't like much; I don't think he's very happy with the film himself. So I missed the film. I had a tape of the film and I kind of watched the Hong Kong scenes and they were not where I was going to...

AUDIENCE 51:17

[INAUDIBLE]

OLIVIER ASSAYAS 51:20

[LAUGHTER] It's Asia and Michael who kind of improvised the stuff. They used the mirror. I wrote the name and they liked the name, it kind of inspired them and so they used it. [LAUGHTER]

HADEN GUEST 51:43

One more question?

AUDIENCE 51:47

[INAUDIBLE]

OLIVIER ASSAYAS 52:08

Well, I like open endings in the sense that anybody can make the sequel, you know? Meaning just when you walk out of the theater, you can make your own sequel. You can imagine whatever. I imagine that Sandra being Sandra, she will go to Shanghai and get herself into some horrible mess. [LAUGHS]

HADEN GUEST 52:44

One final question, why don't you tell us something if you would about your next project, the film L’huere de l'été, which is opening soon?

OLIVIER ASSAYAS 52:53

Okay, so, well, there are actually two next films. Actually I just finished two films. One is a documentary about dance, about choreography and a French choreographer called Angelin Peljocaj and his work with Karlheinz Stockhausen. So it involves also contemporary music , and there's a feature which is opening in France, like next month, like early March, called L’huere de l'été, which is extremely different from what you've seen tonight. I had wanted for a long time to go back to France—well, I’ve never left France. I live in France—but wanted to go back to work with French themes, French characters. And so this is my shot at it. It's in a way like a continuation of a movie I made a while ago called Late August, Early September. It’s very much a movie about characters, France today. It’s with Juliet Binoche, Charles Berling who was in Les destinees sentimentales and Demonlover. Juliet, it's a strange story because I wrote with André Téchiné the movie Rendez-vous, which is the movie that made her famous. It was almost 20 years ago—it was over 20 years ago—it's 1985. And you know, Rendez-vous did really well. It was in Cannes, it did great business and all of a sudden Juliet Binoche was a star. And it really was extremely important in terms of getting things moving for my first feature, so we were very close at that time, Juliet and I. I even offered her my first film, but she was shooting... well, in the end, we never worked together. So it took us like 20 years to find each other.

HADEN GUEST 55:11

Thank you so much.

[APPLAUSE]

©Harvard Film Archive

Part of film series

Screenings from this program

Les Destinées sentimentales

Paris Awakens

HHH – A Portrait of Hou Hsiao-hsien

Boarding Gate