Xala

With Thierno Leye, Myriam Niang, Seune Samb.

Senegal, 1975, DCP, color, 123 min.

French and Wolof with English subtitles.

DCP source: Janus Films

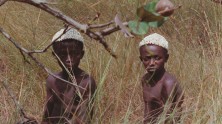

An adaptation of his 1973 novel, Ousmane Sembène’s uproarious Xala condemns the corruption and complicity of African leaders through the symbol of sexual impotence. On his wedding night, businessman El Hadji Abdoukader Beye (Thierno Leye) discovers that a curse of impotence (or “xala”) has been placed upon him. His attempts to remove the curse reach outrageous extremes, exceeding the effort he puts into being a man of integrity. Though Xala harkens back to the dark humor of Mandabi, it demonstrates the evolution of Sembène’s style by deriving its rhythm from a collective protagonist. Dislodged from El Hadji, the film cuts from mistreated wives to greedy subcontractors, then to galvanized peasants—and, as is characteristic of Sembène, from wide and medium to extreme close-ups. Enveloped in shades of blue and brown, Xala also stands out for its moments of playful self-reflexivity: Makhourédia Guèye from Mandabi plays the president of the chamber of commerce, who resembles President Léopold Senghor. The rooms of El Hadji’s children—decorated with a poster for La Noire de… and photographs of pan-African revolutionaries—resemble Sembène’s own office. After the Senegalese government cut twelve scenes from Xala, Sembène responded by distributing flyers indicating which scenes were removed.

After one year of film school in Moscow, Ousmane Sembène returned to Senegal and made Borom Sarret, which he considered to be his “first true short film.” One of the first sub-Saharan African films made in Africa by an African director for an African audience, Borom Sarret follows a day in the life of a downtrodden cart driver in Dakar. The driver’s thankless toil is met with apathy and cruelty, which he endures by clinging to reminders of the past—the praises sung by a griot, a military medal. Sembène was inspired to bring together elements of Soviet cinema and Italian neorealism—specifically Dziga Vertov’s newsreel series Kino-Pravda (1922-1925) and Vittorio De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves (1948). But the film’s narrative structure (a brisk chronology enriched by interstitial digressions), and its stark juxtapositions between foreground and background, are pure Sembène. Most remarkable about Borom Sarret is the fact that it already contains many of his signature motifs and archetypes: bureaucratic red tape, burial rites, wealthy African Europhiles, griots, and the deliberate use of asynchronous French voiceover. The latter, a key feature of Sembène’s sixties output, underscores the colonial implications behind the demands of French co-productions.