Also Like Life. The Films of Hou Hsiao hsien

For three decades, Hou’s work has explored an extraordinary range of artistic propositions: the interactions between individual and collective history, the relationship between China and Taiwan, the link between Time and Space, and the loss of reference points in a world driven by ultra-fast capitalist development, lack of democracy, submission to standardized ways of life, globalization, and new technology. Set in the present and the past, circulating between ages (Good Men, Good Women, 1995; Three Times, 2005) and even into the future (Millennium Mambo, 2001), foreign locations (Café Lumière, 2003; Flight of the Red Balloon, 2007), and dreams, his films constitute a singular universe. This singularity can be described, to a large extent, as the innovative and very personal translation of the canons of traditional Chinese culture into cinematic language. – Jean-Michel Frodon

In effect, Hou’s style—at once intuitive, powerful and contemplative, at a remove from any attempts at seduction, and able to use sheer brute force to head towards the essential and nothing but the essential—boded extremely well for Chinese cinema. Starting from zero, he was able to bring about a veritable revolution in its manner of apprehending and regarding the world, and, overcoming the impasses of classicism and imported modernism, he defined the possibility of a new and original point of view on the contemporary world.

Nothing at the time existed in Chinese cinema that could approach the rough-hewn truth and autobiographical realism of Hou’s early work, which, if we must find a reference point for it, evoked Maurice Pialat’s films. …

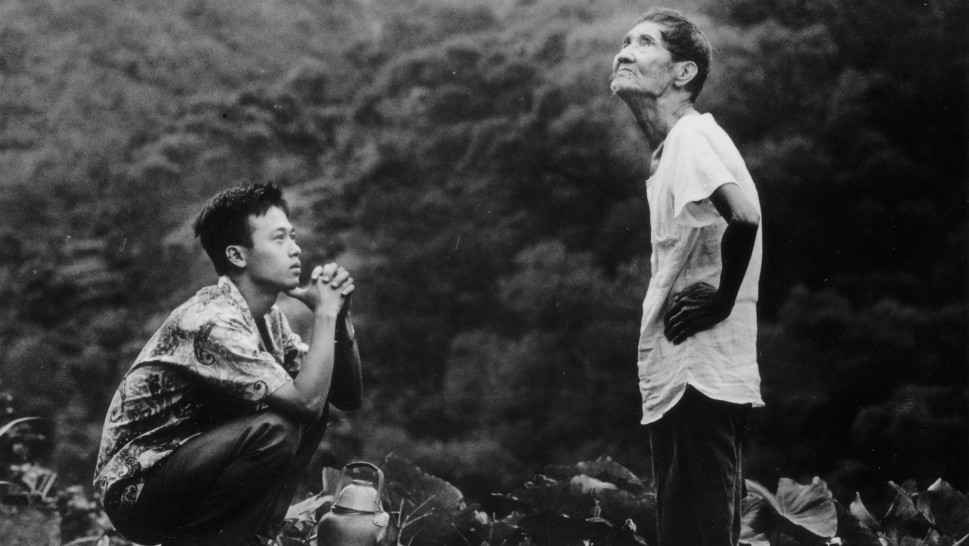

There are several important articulations in his work, and in particular his trilogy on memory initiated with A City of Sadness (collective memory), continued with The Puppetmaster (1993, individual memory) and concluded—or rather interrogated once more—with Good Men, Good Women (1995). Good Men, Good Women is entirely constructed around the conflict between the former and the latter, between the memory which constitutes being, which is the very fiber of being, and the memory of the nation, which can only be the object of an intellectual, voluntarist approach, ceaselessly subjected to approximation and doubt. This is political work, if you want, but it can only be envisaged if the question of personal memory, its intimate conflicts and wounds, is first resolved. That pretty much sums up the evolution of Hou’s oeuvre. …

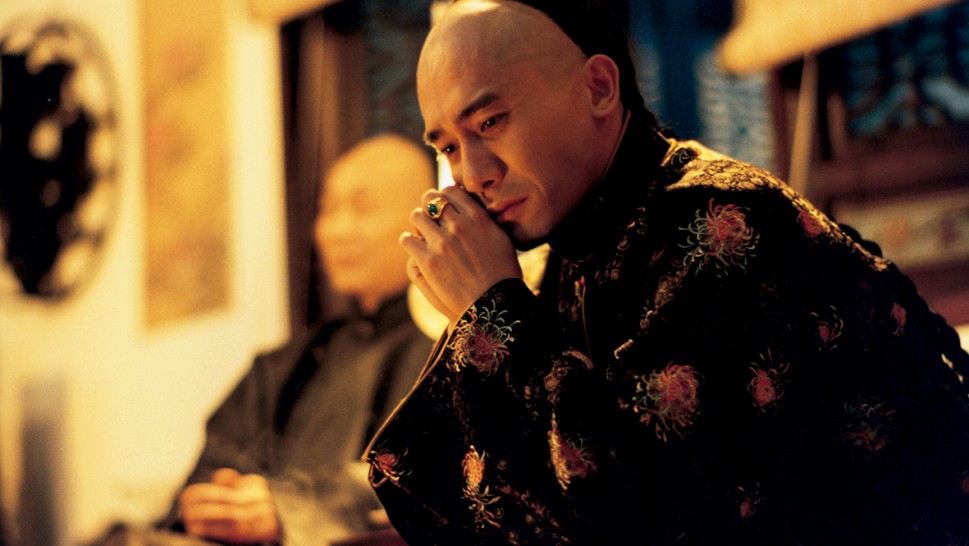

Between the youthful brilliance of his “second debut film” Goodbye South, Goodbye and the vertiginous success of Flowers of Shanghai (1998), where the essence of life itself swirls around among the opium vapors, and where he shows the ungraspable yet inexorable workings of time, Hou has become a universal filmmaker. He is one of the greatest filmmakers working today—in China or elsewhere. When it comes down to it, he was destined to be so from the beginning. – Oliver Assayas, 1998

Beginning as a forerunner of the refreshing, distinctive New Taiwan Cinema, Hou Hsiao-hsien has risen to one of the most critically esteemed filmmakers in the world. The Harvard Film Archive presents all of his feature films, from the earliest low-budget comedies to the New Taiwan filmmakers’ virtual manifesto, The Sandwich Man to his most recent city symphony Flight of the Red Balloon. As a fitting postscript, we are pleased to welcome Hou cinematographer Mark Lee Ping Bin with his own exquisite Springtime in a Small Town on November 3.