As if Our Eyes Were in Our Hands: The Films of Susumu Hani

A Japanese novelist once wrote that we should be very thankful that our eyes are not in our hands, because if they were we would always have to see our own faces. I think this is fascinating concept. Sometimes we can achieve this in the cinema. Of course when you are acting, your ‘eye’ should see your face, but when you view rushes, your eyes are constantly in your hands. I find it extremely interesting to observe the relationship between cinema and the perception of one's own image.

Susumu Hani (b. 1928) is one of the central and most unusual filmmakers of the astonishing New Wave that reinvented Japanese cinema in the late 1950s and 1960s. The director of such indelible, now classic, works as Bad Boys, Nanami: The Inferno of First Love, A Full Life and The Song of Bwana Toshi, Hani forged a unique path through the tumultuous postwar years, pioneering and combining forms of poetic documentary and engaged art cinema to define a singular mode of avant-garde humanism. While Hani's best-known film, Nanami imbibes the same heady cocktail of psychosexual obsession and surrealism as his contemporaries Shohei Imamura and the late Nagisa Oshima, Hani's larger oeuvre reveals the rich diversity of his interests. The son of prominent intellectuals and social reformers, Hani upheld a belief in the cinema as a means of exacting social change while resisting any kind of dogmatism. Beginning in cinema first as a documentarian, Hani directed two stunning short films for the educational film company Iwanami, each about the primary school experience – Children in the Classroom and Children Who Draw – that together offered a remarkably intimate and revealing vision of Japanese children's everyday life and education. Engaging the children themselves in the filmmaking process, Hani's two films count among the very first to explore the documentary as a tool of inquiry into human subjectivity and the imagination.

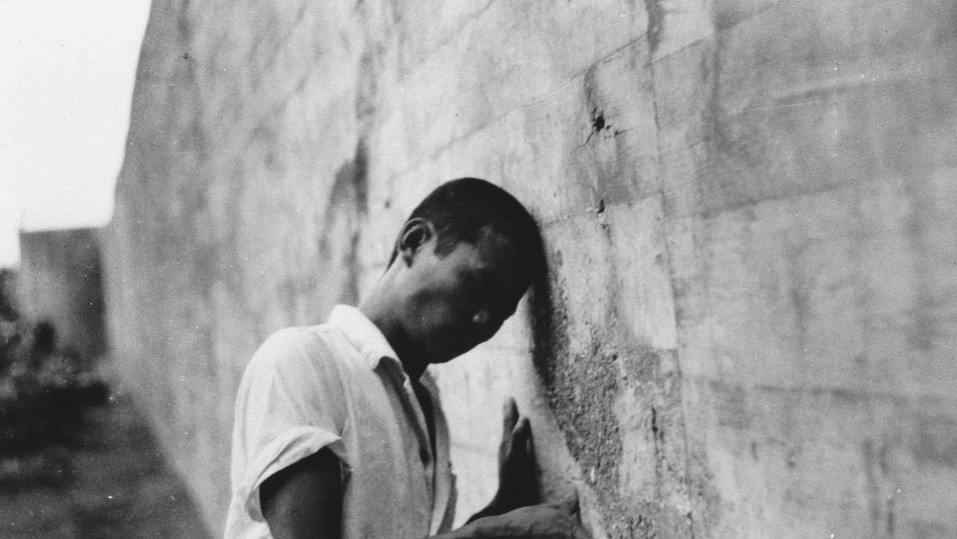

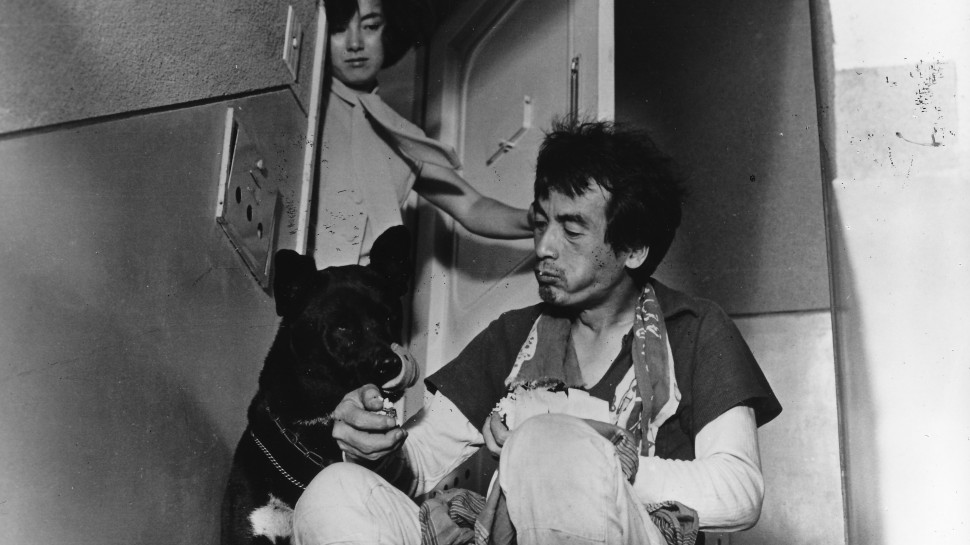

In his extraordinary feature debut, Bad Boys – and its rarely seen follow-up Children Clasping Hands – Hani brilliantly extended his documentary intervention into the realm of narrative cinema, offering boldly frank and unvarnished portraits of Japanese youth that captured their awkward beauty and simmering violence while revealing how familial, social and governmental institutions all ultimately fail to understand the arduous, character-shaping passage into adulthood. Subsequent widely celebrated films such as She and He and A Full Life focused on the status-quo entrapment of middle-class Japanese women, revealing Hani's feminist concerns and the subtle political charge of his cinema. Less expected were his extraordinary, adventurous series of international productions that carried him to South America, Italy and eventually Africa where he filmed The Song of Bwana Toshi, a simultaneously heartfelt and irreverent study of "Japanese-ness" embodied in the figure of a high-strung Japanese engineer transformed by his encounter with tribal culture. Equally unanticipated was Hani's abrupt departure from filmmaking in the mid-1970s, after a brief cycle of nature films inscribed a full-circle return to his documentarian beginnings. Falling outside any easy canon or classification, the unusual arc of Hani's storied career has been largely overlooked, with Hani unjustly remembered only for his most popular, scandalous and award-winning films.

The documentary roots and aspirations of Hani's visionary filmmaking are clear. His films are inspired, above all, by a restless search for ways to vividly render the inner lives and everyday of his characters, whether real-life or fictional, in their fullest complexity. Crucial to this larger project is Hani's striking engagement with non-professional actors and his belief in acting and directing as deeply collaborative arts. In this way Hani crafts his films more in direct response to his actors' personalities and lived experiences than to any preconceived ideas of character or story. While early films such as Bad Boys were shaped around the lives and personae of its non-professional cast, integrating the argot and ritualized sadism of the actual ex-reform school youth appearing within it, Hani would go even further in his strikingly experimental 8mm feature Morning Schedule which used footage shot by the high school student cast themselves. Carefully intertwining the different voices and ever-shifting perspectives of their characters, Hani's films offer choral, kaleidoscopic and politically charged portraits of disenfranchised communities and subcultures torn directly from the postwar experience, from the draconian reform school in Bad Boys to the seedy Tokyo underworld of Nanami. The rare energy of Hani's cinema draws from the rich texture and nuance of the diverse worlds it so boldly explores and the ways in which his camera engages and empowers both subject and spectator.

The Harvard Film Archive is thrilled to welcome Susumu Hani for a rare visit to the US, together with his wife, actress and producer Kimiko Nukamura. — Haden Guest

This series is presented in conjunction with a major symposium on the films and career of Susumu Hani, presented by the Reischauer Institute on Monday January 28.