Free Radical: The Films of Len Lye

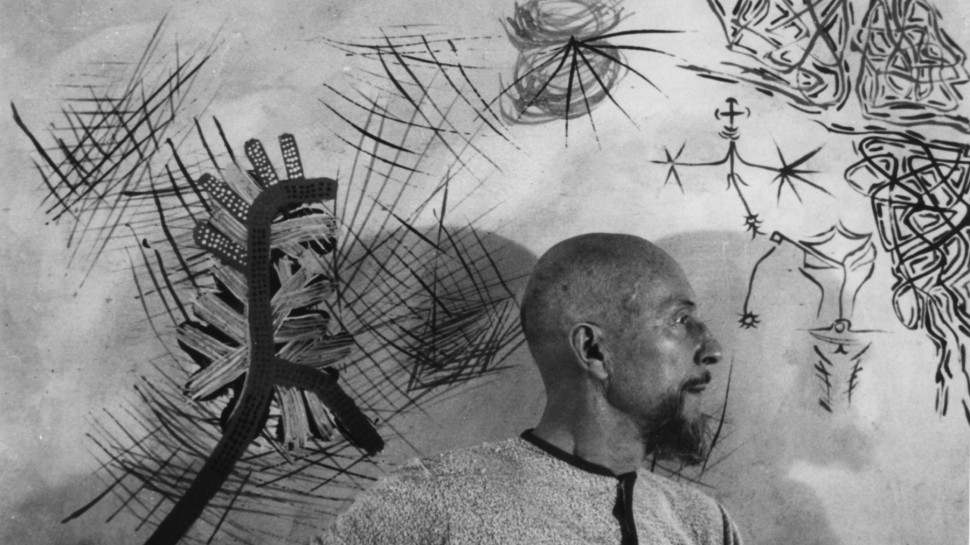

A pioneer of direct-animation, Len Lye (1901-1980) was also a highly innovative painter, photographer and poet, as well as an important figure in kinetic sculpture. Born in New Zealand, Lye left home as a young man in search of film activity and the stimulation that would satisfy what he called his preoccupation with art and movement. Inspired by the primitive imagery of South Sea island art and film’s power to present dance ritual and music, Lye’s experimental – and often revolutionary – camera-less techniques attracted the attention of John Grierson and Alberto Cavalcanti of the General Post Office Film Unit in London, which sponsored Colour Box and other films. Although Lye’s filmmaking had nearly ceased by the late 60s, he continued to speak of his belief in cinema as “the Cinderella of the fine arts. Her beauty lies in her kinesthesia… The fine art film requires urgent consideration.”

This early experimental film premiered at the London Film Society. It imagines the beginning of life on earth, as single-cell creatures evolve into species with distinct identities. Jack Ellitt’s original percussive piano score has unfortunately been lost and the film is now screened silent.

Lye’s first direct film, which combines popular Cuban dance music with hand-painted abstract designs, amazed cinema audiences. Color was still a novelty, and Lye’s direct painting on celluloid creates exceptionally vibrant effects. The film won several major awards, though some festivals had to invent a special category for it, and in Venice, the Fascists disrupted screenings because they saw the film as ‘degenerate’ modern art. A Colour Box was funded and distributed by John Grierson’s GPO Film Unit on the condition that Lye include postal messages at the end.

-

Kaleidoscope

Directed by Len Lye.

UK, 1935, 16mm, color, 4 min.

For Kaleidoscope, which was sponsored by Churchman Cigarettes, Lye animated stenciled cigarette shapes and is said to have experimented by cutting out some of the shapes so that the light of the projector hit the screen directly. As in A Colour Box Lye uses music by Don Baretto and his Cuban Orchestra.

-

The Birth of the Robot

Directed by Len Lye.

UK, 1936, 16mm, color, 7 min.

This experiment was a “prestige advertisement” for Shell Motor Oil.

As conventional animation became dominated by Walt Disney, many European filmmakers turned to puppets as an alternative, and Lye enlisted the help of avant-garde friends such as Humphrey Jennings and John Banting to make the amusing puppets. Exploring the still-complex color process, which involved the combination of three separate images, Lye creates such a vivid storm scene that reviewers hailed it as “proof that the color film has entered a new stage.” The music is Holst’s The Planets.

This live-action film exploits the triple images of the Gasparcolor system in an unprecedented way. Lye filmed dancer Rupert Doone in black and white, then colored the footage during the development and printing of the film, adding stenciled patterns. Rainbow Dance is packed with new filmic ideas such as moving figures that leave behind a trail of colored silhouettes (as in Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase). The film was sponsored by the GPO Film Unit on the proviso that Lye include a Savings Bank advertisement.

-

Trade Tattoo

Directed by Len Lye.

UK, 1937, 16mm, color, 5 min.

Print source: British Post Office

Trade Tattoo went even further than Rainbow Dance in its manipulation of the Gasparcolor process. The original black and white footage consisted of outtakes from GPO Film Unit documentaries such as Night Mail. Lye transformed this footage in what has been described as the most intricate job of film printing and color grading ever attempted. Animated words and patterns combine with the live-action footage to create images as complex and multi-layered as a Cubist painting. Music was provided by the Cuban Lecuona Band. With its dynamic rhythms, the film seeks (in Lye’s words) to convey “a romanticism about the work of the everyday in all walks of life.”

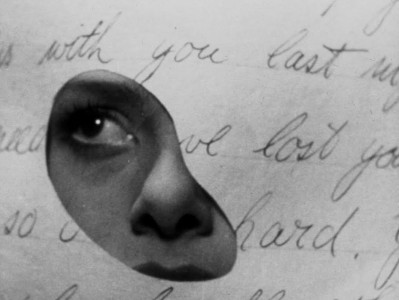

When Lye was commissioned by the GPO Film Unit to make a live-action film about the need to be careful in addressing letters, he decided to make an experiment in subverting the orthodox language of film editing (which he described contemptuously as “the Griffith technique”). A simple story about a lovers’ quarrel becomes a montage of bizarre camera angles and point-of-view shots, accompanied by lively jazz music. Lye’s favorite sequence (showing the young woman getting dressed and going for a walk) was so extreme that the Film Unit cut it and it has since been lost, but the surviving seven minutes of the film are still astonishing.

This riot of color was a showcase for Lye’s hand-painted and stenciled imagery. Sponsored by Imperial Airways, it incorporates the airline’s “speedbird” symbol, and the music consists of “Honolulu Blues” by Red Nichols and a rumba by the Lecuona Cuban Boys. Time Magazine raved about the film, describing Lye as England’s alternative to Walt Disney (a David-and-Goliath comparison!). Like Lye’s other films, Colour Flight was not eligible for distribution in the US due to its status as an overseas advertising film.

Lye edited together “swing” versions of the popular Lambeth Walk (including Django Reinhardt on guitar and Stephane Grapelli on violin), combining them with a particularly diverse range of direct film images, scratched as well as painted. He was particularly pleased with a final guitar solo (with a vibrating horizontal line) and double bass solo (with a stomping vertical line). For this film Lye did not have to include any advertising slogans; friends at the Tourist and Industrial Development Association, shocked to learn that Lye and his family had become destitute, arranged for TIDA to sponsor the film – to the horror of government bureaucrats who could not understand why a popular dance was being treated as a tourist attraction.

-

Musical Poster #1

Directed by Len Lye.

UK, 1940, 16mm, color, 3 min.

During World War Two, Lye—adamant that wartime films did not have to be gloomy—made a number of films to assist the war effort. Musical Poster #1 (part of a long tradition of British “poster” films) was not only screened in cinemas but taken to factories and village halls by the Ministry of Information’s traveling film units. The film alerted the public to the risk that German sympathizers might overhear information about the war effort in everyday conversation.

-

Color Cry

Directed by Len Lye.

US, 1952, 16mm, color, 3 min.

In 1944 Lye moved to New York City, initially to direct for the documentary newsreel The March of Time. He settled in the West Village, where he mixed with artists who later became the Abstract Expressionists, encouraged New York’s emerging filmmakers such as Francis Lee, taught with Hans Richter, and assisted Ian Hugo on Bells of Atlantis. Color Cry was based on a development of the “rayogram” or “shadow cast” process, using fabrics as stencils, with the images synchronized to a haunting blues song by Sonny Terry, which Lye imagined to be the anguished cry of a runaway slave.

-

Tel Farlow

Directed by Len Lye.

US, 1980, 16mm, black & white, 2 min.

Lye created a series of scratched images in the 1950s – more regular or geometric than his usual style – to accompany Rock ‘n’ Rye, a track by jazz guitarist Tal Farlow, but he did not get far with the editing. He returned to the material in 1980 but died before it was completed. His assistant Steven Jones finished the film under the supervision of Lye’s widow Ann, who had been closely involved with all of Lye’s American films.

-

Rhythm

Directed by Len Lye.

US, 1957, 16mm, black & white, 1 min.

Intended as a publicity film for Chrysler, Rhythm uses rapid editing to speed up the assembly of a car, synchronizing it to African drum music. The sponsor was horrified by the music and suspicious of the way a worker was shown winking at the camera; although Rhythm won first prize at a New York advertising festival, it was disqualified because Chrysler had never given it a television screening. P. Adams Sitney wrote, “Although his reputation has been sustained by the invention of direct painting on film, Lye deserves equal credit as one of the great masters of montage.” And in Film Culture, Jonas Mekas said to Peter Kubelka, “Have you seen Len Lye’s 50-second automobile commercial? Nothing happens there…except that it’s filled with some kind of secret action of cinema.”

In arguably his greatest film, Lye reduces the medium to its most basic elements by scratching designs on black film. He used a variety of scribers ranging from dental tools to an ancient Native American arrowhead, and synchronized the images to traditional African music (a field tape of the Bagirmi tribe). The film won second prize in the International Experimental Film Competition, which was judged by Man Ray, Norman McLaren, Alexander Alexeiff and others at the 1958 World’s Fair in Brussels. In 1979 Lye further condensed the film by dropping a minute of footage. Stan Brakhage described the final version as “an almost unbelievably immense masterpiece (a brief epic).”

-

Particles in Space

Directed by Len Lye.

US, 1979, 16mm, black & white, 4 min.

In his last great film, completed a few months before his death at the age of 78, Lye returned to the black-and-white techniques of Free Radicals and his “white ziggle-zag-splutter scratches in quite doodling fashion,” exploring some “particularly vibrant, ziggy little images” reminiscent of the freest and most vigorous forms of Abstract Expressionism. The soundtrack combines Jumping Dance Drums from the Bahamas with drum music by the Yoruba of Nigeria and the sounds of Lye’s metal kinetic sculptures.