The Complete Alfred Hitchcock

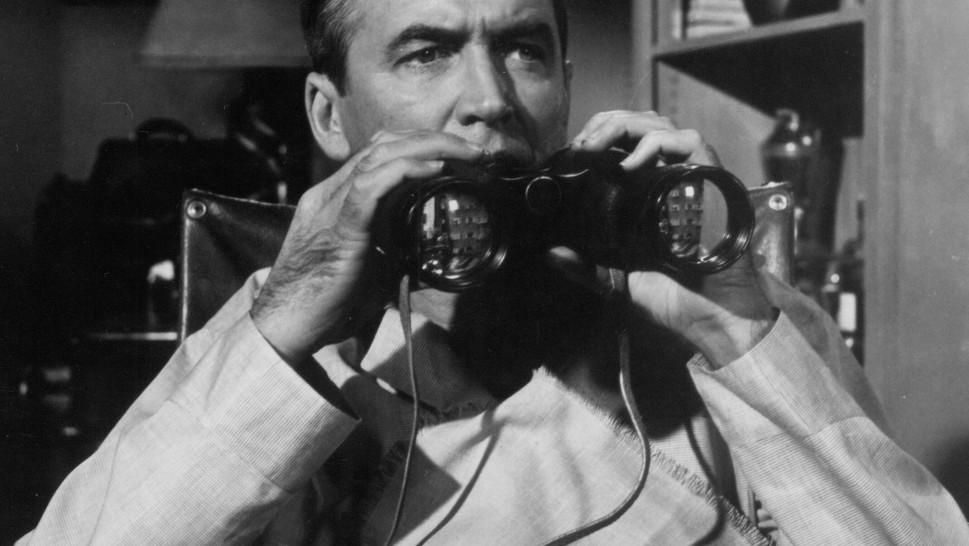

Where the critic Robin Wood once felt it necessary to pose the rhetorical question, “Why should we take Hitchcock seriously?,” the complete retrospective before us, including its new restorations of nine of Hitchcock’s extant silent features, begs a different question: When did Hitchcock become Hitchcock? It would take time for the director’s formal and moral fixations to cohere as the compound effect known all too simply as “suspense,” but there is no mistaking the master’s touch in the persistent ambiguities of The Lodger, theobsessive reiterations of the circle motif in The Ring, the menacing voyeur crowding the edges of Champagne, or the spiraling delineation of guilt in the silent Blackmail. Even within the seemingly inhospitable confines of a comedy of manners (Easy Virtue) or melodramatic fall (Downhill), the young Hitchcock experimented with different styles of point-of-view and disclosure, ever attentive to the audience in relation to the characters. The director learned Expressionism during an early apprenticeship at Berlin’s UFA Studio and Soviet-style montage from London Film Society screenings, quickly absorbing both styles into his own deeply intuitive grasp of entertainment as moral reckoning. Already in the silent films we see the interpolations of subjective and objective viewpoints, the rupture of fantasy in authentic settings, the condensation of whole characterizations into discrete details, and the genius for soliciting the audience’s complicity. From the very first, a Hitchcock film lays special claims to our role as viewer.

So fully did Hitchcock match his preoccupations to a distinctly cinematic language that they now seem like basic conditions of narrative film. Whenever a critic theorizes Hollywood’s construction of the “gaze,” you can be sure that Hitchcock is not far behind. The “Hitchcocko-Hawksians” at Cahiers du Cinéma fashioned auteurism from close study of his films, even as his signature cameo appearances give the impression of a preemptive gag on their directorial obsessions. Gus Van Sant’s shot-for-shot remake of Psycho is only the most literal reflection of the director’s haunting afterlife in the post-classical imagination. Even Hitchcock’s self-mythologizing, his image of himself as a showman, seems quintessentially modern, a brilliant piece of conceptual art before there were such a thing. Hitchcock’s influence cuts across Hollywood and the avant-garde, academia and the art world; more than thirty years after his death, his life and work remains the subject of endless speculation and interpretation. For undergraduate film students, close analysis of a Hitchcock sequence has long been a rite of passage, the equivalent of memorizing your Shakespeare. There is simply no getting around him.

Not that we would ever desire such a shortcut. In the same way that Hitchcock’s mature masterpieces always reward another look, so the lesser works invariably offer a fresh vantage from which to consider his passionate artistry. Hitchcock was the rare filmmaker to successfully traverse several distinct eras of film history: from silent to sound, Gainsborough Studios to Hollywood independent, Technicolor to television. “Summing it up,” the director told François Truffaut, “One might say that the screen rectangle must be charged with emotion.” So it was, and so it is still. – Max Goldberg, writer and frequent contributor to CinemaScope