The Complete Robert Altman

Although he is usually remembered as part of the “New Hollywood” wave of the 1970s, Robert Altman (1925-2006) was chronologically part of the generation of Sidney Lumet, Stanley Kubrick and John Cassavetes, all of whom were born in the 1920s. But while those men had all achieved some measure of success by the end of the 1950s, Altman was forty-four and had made five feature films before M*A*S*H brought him his first real acclaim. He would go on to become arguably a more innovative filmmaker than any of his contemporaries (including younger directors like Scorsese, Coppola, Bogdanovich or May) with his drifting camera and decentered shot composition, his experiments with cinematography and sound recording, his use of overlapping dialogue and ensemble casts, and his disregard for conventional narrative structure.

Born and raised in Kansas City, Altman left junior college in 1945 to enlist in the Air Force. Stationed first in Southern California and then in the South Pacific, Altman spent the postwar years bouncing between Los Angeles and New York, trying his hand at writing songs and screenplays before returning to Kansas City to work for the Calvin Company, a major producer of industrial films. He worked there for almost a decade, learning how to make movies while also working on local independent productions, which led to his being hired to direct his first feature, The Delinquents, shot in Kansas City in 1956.

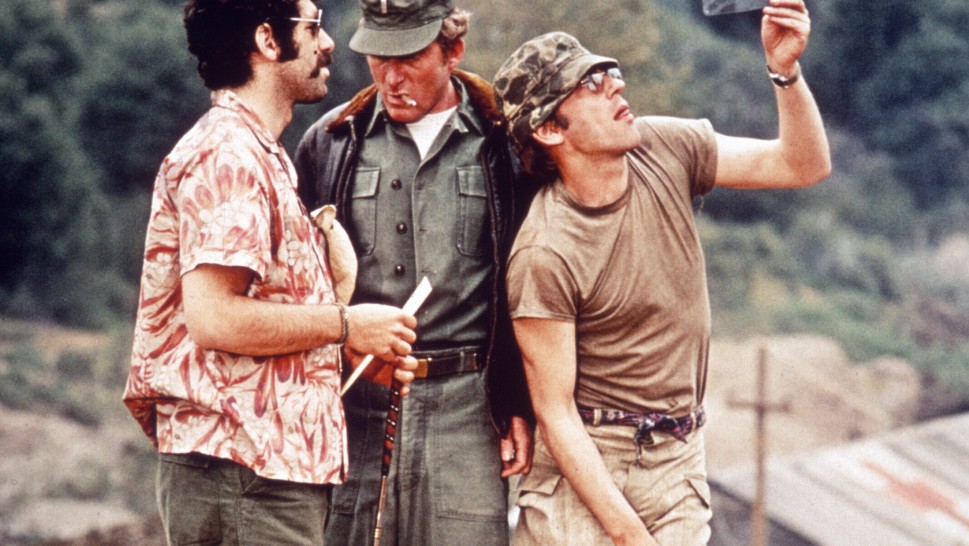

Altman relocated to Los Angeles for good the following year and began working as a director for television, with his big break coming from none other than Alfred Hitchcock, who hired him to direct two of episodes of Alfred Hitchcock Presents after seeing The Delinquents. For the next decade, Altman directed episodes for several series and became one of the most sought-after television directors. This led to his being hired to direct a B-movie for Warner Brothers (Countdown), followed by an independent feature film (That Cold Day in the Park), and finally M*A*S*H, the most successful movie Altman ever directed and the achievement that launched the string of 1970s films that helped define that creative decade in American cinema.

Despite the acclaim they received, McCabe and Mrs. Miller, The Long Goodbye and Nashville were not commercial successes; by the end of the 1970s, even the critics had deserted Altman in the wake of idiosyncratic films such as Buffalo Bill and the Indians, 3 Women and Popeye. In the early 1980s, when Altman found himself unable to make a film at any of the studios, he turned first to directing theater and then to filming low-budget versions of such plays as Come Back to the 5 and Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean; Fool for Love and Streamers. By the end of the 1980s, Altman’s work of a decade earlier (especially 3 Women)was already being rediscovered, and the success of both The Player in 1992 and Gosford Park in 2001 guaranteed that he could continue to direct at a regular pace, if not at the breakneck speed of the 1970s, until his death in 2006.

Altman’s legacy is still being determined, in part because of the size and variety of his oeuvre. Although collaboration was crucial to his work, he remained an individual and idiosyncratic director. He loved classical Hollywood filmmaking even as he delighted in satirizing the industry and its history, turning increasingly to European cinema (Fellini, Renoir, Bergman) for inspiration. His disregard for storytelling kept him at the margins of the film industry, even as his love for actors, and their love for him, meant that he was able to work with almost every major star of the past fifty years. If he disdained narrative, he loved situations, using plot more as a way of throwing his characters together in various combinations rather than as a unifying thread. With his combined love of and derision for tradition, his assertions of individuality together with his need for community, his mixture of high and low, and his alternations between delicacy and crassness, Altman seems a uniquely American figure. If Griffith and Vidor are the quintessential American filmmakers of the first third of the 20th century, with John Ford taking over for the middle decades of the century, Altman is their equivalent for its turbulent final third. – David Pendleton

This retrospective includes all thirty-seven theatrical features directed by Altman, the feature films he directed for television in the 1980s, and a selection of his industrial films and shorts. It does not include any of the television specials or the many hours of episodic television that he directed.