Audio transcription

John Quackenbush 0:01

April 10, 2015, the Harvard Film Archive screened The Hourglass Sanatorium. This is the audio introduction by HFA Director Haden Guest and historian Annette Insdorf.

Haden Guest 0:15

My name is Haden Guest. I'm Director of the Harvard Film Archive. And I want to ask everybody, please, first of all, turn off any cell phones, any electronic devices that you have on you and please refrain from using them during the course of what I promise you, will be a really extraordinary cinematic voyage. Because tonight launches a retrospective that we've been very excited for for a long time. It's been a long time coming. And this is a retrospective of the great visionary Wojciech Has, one of the seminal figures of the Polish cinema that reached a real and very important climax in the postwar, World War II years.

It’s a fourteen-film series. Many of the prints we'll be seeing are rare and are coming all the way from Poland. And I want to thank the Adam Mickiewicz Institute in Warsaw for their support of this program. They're really wonderful partners, and we're so grateful for their support. I also want to thank tonight's very special guest, Annette Insdorf, who is a professor of film at Columbia University. She has written a very insightful and original book about Krzysztof Kieslowski, another on cinema and the Holocaust, and she's working right now on a book on Has. So we have an expert on Has’ truly remarkable and unclassifiable cinema. Annette Insdorf will be here again tomorrow night to introduce Has’ feature debut The Noose, as well as Harmonia, an early short. And Professor Insdorf has kindly offered to answer any questions people might have in the lobby after the screening of tonight's film, which is The Hourglass Sanatorium from 1973. Considered, I think, one of the high points of Has’ career, it was a film that was almost suppressed and yet it found its audience, and it's kept aside. It's considered both a cult, a kind of underground film and at the same time, a true masterpiece of art cinema. To tell us more about this film and about Wojciech Has, we have with us, Annette Insdorf!

[APPLAUSE]

Annette Insdorf

Sorry, I’m clearly not as tall as Haden Guest. So I will just try to do this and not be hidden from view. I've been teaching Polish cinema for decades. But the reality is that my syllabi at Columbia University have been dominated by the names that you probably know: Andrzej Wajda, Roman Polanski, Krzysztof Zanussi, Krzysztof Kieslowski—who was the subject of my book Double Lives, Second Chances—so the director of Poland's Adam Mickiewicz Institute tried to convince me to devote my critical attention to the work of Wojciech Has. And I said “no” twice. First of all, his films were not available on DVD in the United States or in any other format, for that matter. And second of all, never having met Has, I felt that I would be at a disadvantage because I would not have the personal input that informed my previous books on Francois Truffaut, or Kieslowski, or Philip Kaufman. But I remembered the impact that one or two Wojciech Has films had on me in my youth, and that led me to reconsider and to delve deeper.

To be honest with you, I first heard the name of Wojciech Has in the early 1970s when I attended a midnight screening of The Saragossa Manuscript at Manhattan's Elgin theater. Although I had never taken LSD, by the time the three hour film ended at three o'clock in the morning, I was convinced that I had experienced a drug-induced high. There was something hallucinatory about this story within a story within a story and the narrative displacement of a Polish movie that is set in Spain centuries earlier. And I also found something kind of fascinating: the ironic treatment of men besotted by semi-naked women. Then about a few years later, there was a special screening at Manhattan's Hunter College, and I decided to go. My mother was teaching French literature there. And the reason I went is that it was the same director, and I got to see The Sandglass, otherwise known as The Hourglass Sanatorium.

And I was shocked in a way because—apart from the phantasmagorical elements that Haden mentioned, that you're about to see—I had never seen such a vivid if surreal depiction of Jewish life on screen, because he deals with the Hasidic world in Poland between the wars. It took Has five years to make The Hourglass Sanatorium. It was released in ‘73. But he wrote the screenplay based on the stories of Bruno Schulz called Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass, published in 1937. Schulz, a Jewish writer who has been called Poland's Kafka, was murdered by a Gestapo officer in 1942 for stepping outside of the ghetto of his Polish town, in Galicia. Given the film’s striking and pervasive Jewish iconography, it can be seen as this layering of at least three timeframes: the prewar Poland of Schultz's stories, the Holocaust, and postwar Poland marked by, I think, the ghosts of dead Jews.

Visually and orally, Has interweaves the theme of time. The very title in Polish, Sanatorium pod klepsydra, actually has a double resonance because klepsydra means not simply the hourglass device, but an obituary notice. The film thus takes place under the sign of death. And the sandglass is indeed disorienting and nightmarish. Less a linear account, than a composition of internal rhymes, stories within stories that conform to the logic of dreams. Moving through dreamscapes of dilapidation, the constantly tracking camera of Witold Sobocinski conveys this rich darkness and given the prevalence of a self-conscious, low-angle camera, as well as dissonant sound design—meaning emerges through these surreal visual and aural juxtapositions.

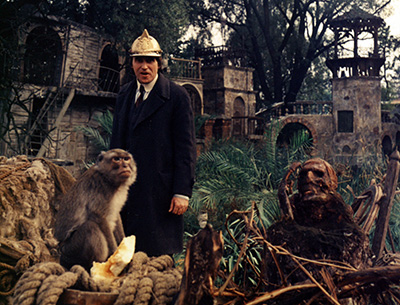

The plot is not easy to recount. You're going to follow Jozef, played by the great Polish actor Jan Nowicki. He travels by train to visit a sanatorium where his father is dying. He discovers this crumbling space surrounded by gravestones, and a mysterious doctor who seems to keep the patients in a suspended state between living and dying. As with all of Has’ films, you have to pay very close attention to the opening scene, because it introduces elements that will be developed throughout the film. For example, you've got this wide-angle lens, and it prepares for the perspective of a child, while reminding us that we too are in a movie theater looking up at the screen and subject to entrapment, because as you'll see, in many shots, the ceiling often bears down on the characters. Moreover, the distorting lens invokes this subterranean or hellish perspective, and that's consistent with Jozef often disappearing underneath a bed or a table, crawling amid debris into a new space. The surrealist imagery that informs the film you're about to see, leads us to question what we see. Like so many Polish filmmakers Haas was not very interested in just adapting a story where the plot and the characters can be recounted easily. I think he, like Kieslowski and Wajda, was really interested in creating some kind of complicity with the viewer, making us far more active participants in unraveling meaning. I'll talk tomorrow night a little bit more about the origins of this and how he developed in the 1950s, but for the moment, let's just say that Has’ film serves as a dreamspace, a locus of poetic associations that really externalize the internal landscape of the character.

You'll see how the sound design is equally rich throughout, beginning with the eerie tones of the first shot, followed by the sound of crows. Having watched almost all of his films, I can tell you, whether it's crows or ravens, boy, do they keep popping up in his films in a very unsettling manner. In the sanatorium, you'll hear the agitation of symbols as well as voices and later water dripping. The atonal score by Jerzy Maksymiuk, not only expresses this off-kilter universe, but also includes klezmer melodies, the music of the Eastern European Jews, in the last sequence.

Has is very much exploring time, especially through cobwebs, which give graphic shape to the passage of time. In the first scene, you'll see how one of the passengers in the train is this clock. Later Jozef says about the sanatorium, “It's regurgitated time, secondhand time,” a line that's taken directly from Schulz’ story, whose narrator speaks of quote, “used up time worn out by other people, a shabby time full of holes like a sieve.”

Reading Schultz's tales alongside watching the film is extremely instructive. Because the deletions and the amplifications of the prose, they suggest an even darker labyrinth that houses presenting than anything Schulz was imagining. While resurrecting prewar Galacia, the film contains also a biblical resonance, considering that the main character is Jozef and his father's name is Jacob. And at one point in the film, somebody even asks him if he dreamed the dream of the biblical Joseph. But you'll see the allusion is probably ironic.

So given the prevalence of this Jewish iconography, Has seems to be breathing magical life into a long gone world. The train of the opening sequence, it connotes something much darker in 1973 than in 1937. As you'll see, it carries Jews who look almost dead, and is therefore a prophetic image of the way that the Nazis transported their victims to the concentration camps. The crumbling space of the sanatorium conveys the sense of Poland as the graveyard of an entire people. The question for me is: was Has drawn to Schulz’ stories because his own father was allegedly Jewish? Perhaps. I don't know for sure, but I can tell you that I went to Poland in June, and I tried to ascertain by visiting Warsaw, Krakow and Wodz. What Has’ ancestry was like, what would have been leading him, for example, to adapt the work of Jewish writers like Bruno Schulz or Kazimierz Brandys for How to Be Loved. Wikipedia, by the way, claims that his father was Jewish, but I never completely trust that. Has never publicly identified as a Jew. No surprise given that during World War II, that would have been tantamount to a death sentence. But I think the films convey something that relates at the very least to the sense of an internal exile—stories of marginalized outsiders who have no place of their own. Whereas some of the people that I interviewed said that Has was not Jewish, that they had no evidence of it, a few offered stories that he was. Whether Has was half-Jewish, or identifiably so, is ultimately not crucial. However, for me, this question provides yet another strain in a body of work that is eminently worthy of sustained attention.

Finally, it is no surprise that the Polish authorities were not very pleased with The Hourglass Sanatorium. Some were uncomfortable with Has’ sympathetic depiction of Jewish life a mere few years after the Polish government expelled 30,000 Polish Jews. Others interpreted the decaying sanatorium as a symbol of the rundown institutions of Poland. Although Has was not officially permitted to submit The Hourglass to the 1973 Cannes Film Festival, a print was smuggled to France. And the jury presided by Ingrid Bergman voted it the Jury Prize. Wojciech Has was not able to make another film for ten more years.

And now The Hourglass Sanatorium…

[APPLAUSE]

©Harvard Film Archive