Photographer, cinematographer and filmmaker James E. Hinton (1936-2006) was an African American trailblazer whose work influenced the trajectory of African American cinema. His career began as the civil rights movement was gaining momentum.

During his student days at Howard University in the 1950s, Hinton studied political science with influential scholars such as William Leo Hansberry, whose teaching fostered Hinton’s interest in historiography. Hired by Dev O’Neill, official photographer for the US House of Representatives, Hinton began working as a darkroom technician on Capitol Hill to finance his studies. He had initially begun experimenting with darkroom techniques at the age of fourteen, when his elementary school teacher mother purchased darkroom equipment for him to use at their home in Atlantic City, New Jersey. Hinton’s early technical expertise would later inform his eye for cropping and letting the skin tonalities of his photographic subjects “go Black” to reflect the full diversity of skin hues in his photography and film.

Following his university years, Hinton completed his draft-era military service stateside, later moving to Chicago, where he worked as a photographer and began exhibiting as early as 1963. After relocating to New York City in 1965, Hinton trained with Roy de Carava at the highly regarded Kamoinge workshop and continued to photograph for Black-issue publications and news outlets.

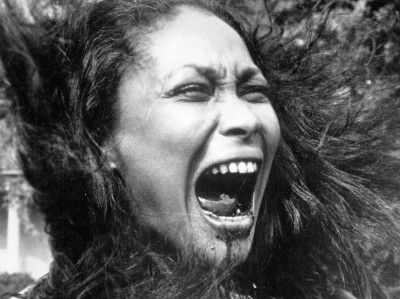

Hinton’s photography career had a deep influence on his development as a filmmaker. He documented some of the most emblematic figures of the civil rights era—including Martin Luther King Jr., Mahalia Jackson, Fannie Lou Hamer, Myrlie Evers, Adam Clayton Powell, Robert F. Kennedy, James Farmer, Huey Newton, Stokely Carmichael, Muhammad Ali, Gwendolyn Brooks, Miles Davis and Thelonious Monk.

In addition to photographing towering historical figures, Hinton captured thousands of images of Black-owned businesses, social gatherings, school integration efforts, and the activism, beauty and creativity of ordinary men, women and children. His photographs also reflected many of the needs, opportunities, contradictions and limitations of this turbulent time period, underscoring problems in education, housing, health care and the impact of drugs and policing. Hinton’s work also highlighted the daily efforts and spirit of Black political organization. Photographing primarily in New York, Chicago, Atlanta, Mississippi, California and Washington D.C., Hinton documented anti-war rallies, demonstrations, strikes, protests, and activities of organizations such as the Congress on Racial Equality, the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, Committee for a Unified Newark and Harlem Youth Opportunities Unlimited.

Hinton’s civil rights photography resulted in an archive of more than 40,000 images. Given the limited distribution outlets for his work, the vast majority of his collection remains unseen; digitization by Emory University is underway. His printed photographs are in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery, Library of Congress, Emory University and the High Museum of Art.

Hinton’s photographic lens, eye for social commentary and interest in historiography continued to guide him as he moved into film production. Captivated by the strength of the motion picture as a dynamic medium of communication and consciousness, Hinton began in the 1960s to turn increasingly towards moving images, simultaneously working as a documentary photographer and a freelance film cameraman. He covered news events, producing footage and segments on the Columbia University student takeover, the Pentagon Vietnam anti-war demonstrations and the Poor People’s March on Washington that were used by NBC, CBS, the BBC, Rai-TV, Metro-Media and WNET. Hinton also served as a freelance director and cameraman for the New-York based Metro-Media (WNEW-TV Channel 5) program Black News—developed as an alternative to Black Journal—airing on NET/PBS.

In the late 1960s, Hinton founded a film collective known as Harlem Audio Visuals with Larry Neal, Edwards Spriggs, Rufus Hinton (no family relation) and Douglas Harris. This effort was intended to generate meaningful film production opportunities for African Americans that would reflect the pressing preoccupations of the time, raise consciousness, and provide a counter narrative to negative historical stereotypes. Hinton later founded his own production company James E. Hinton Productions in 1971. Several notable African American film industry professionals, including Sam Pollard, received their first opportunities on Hinton films.

During this period, Hinton was also active in African American arts promotion, serving as a founding board member of the Studio Museum in Harlem from 1967-1980. Opportunities for Black artists were limited, and Hinton played an important role in the development of the institution as a center for community-based arts education, as an exhibition site for under-represented Black artists, and as a vector for exchange between Black artists and society. Harvard Professor Henry Louis Gates Jr. serves on this board today, together with other prominent philanthropic, business, legal, civic and arts leaders from New York City and beyond.

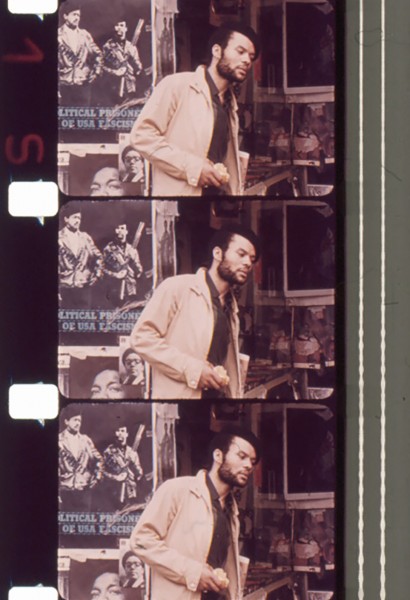

In the late Sixties, Hinton filmed the documentary The New-Ark for director Amiri Baraka (known as LeRoi Jones at the time). The film focuses on black education, urban public theater and political consciousness-raising inside and outside of Spirit House—Baraka’s Black nationalist community center. Lost for years, it was recently rediscovered at Harvard in 2014. After digitization, it received a second life, including a screening at Rutgers in Newark.

In 1973, Hinton was hired as the cinematographer on the feature film Ganja and Hess, where he used his experience as a documentary filmmaker and photographer to bring the techniques of cinema verité to the shooting style of the film. A groundbreaking film for the period, Ganja and Hess, became renowned for its all-Black cast and its scenes of elegant, multi-lingual African Americans imbibing blood instead of martinis. With Ganja and Hess, Hinton changed the look of African American filmmaking by insisting that the skin tones of the Black actors and actresses in the film not be lightened photographically, a technique which was standard at the time. This film received the Critic’s Choice Award at the Cannes Film Festival. Ganja and Hess’ distribution opportunities in the United States were stymied, however, and the film was recut, re-edited and re-titled several times by the film studio. The plot was disrupted but the innovative quality of Hinton’s shots remained. The Museum of Modern Art preserved the director’s cut and the original film was re-released in 1998. Spike Lee subsequently remade the film in 2014.

Hinton also played an important role in the development of the 1984 film, The Cotton Club, directed by Francis Ford Coppola. Hinton sought to develop the book of the same name—written by African American author Jim Haskins—into a feature film. The actual Cotton Club—a jazz nightclub located in the heart of Harlem—had been a prohibition era "whites-only" establishment in the 1920s and 1930s run by organized crime. The club headlined Black performers such as Duke Ellington to play for white audiences until Ellington was able to push for a partial relaxation of the "whites-only" patron policy. Unable to obtain the financing to produce the film, Hinton and a business partner eventually sold the rights of The Cotton Club to producer Robert Evans in 1983. The film subsequently became a high budget Academy Award nominated motion picture film starring Richard Gere and Gregory Hines.

Over the course of his career, Hinton generated more than seventy film credits. As he aged into his fifties and sixties, Hinton began to focus on teaching and promotion of the arts, serving as program director for the Children’s Art Carnival in Harlem in the mid-1990s, also teaching cinematography at SUNY Purchase College, New York.

A resurgence of interest in Hinton’s civil rights era photography began after a Library of Congress acquisition of eighteen of his photographs in 1999 which led to a flurry of exhibitions, lectures and museum acquisitions of his work. Hinton’s hope was that his film and photographic collection could one day be digitized. He sought to provide historians and young people with a visual frame for more robust teaching and learning of the 1960s era, a period he believed to be fundamental to the history of democracy in the United States.

About the Collection

The films of James E. Hinton were donated to the HFA in 2008 by his daughter, Dr. Mercedes S. Hinton. Genres in the collection range from feature films to documentary, educational, and industrial shorts and commercials on a range of topics—from African American history, arts in education and in the community, to films about music, including footage from an unfinished documentary on Dizzy Gillespie. Hinton's role in the production of titles in the collection ranges from director to cinematographer to producer, and many elements and titles represent the work of both Harlem Audiovisuals and Hinton Productions.

More detail on the collection and a complete inventory is available on the James E. Hinton Collection, 1968-1992 : Finding Aid.

Related Material

James E. Hinton photographs and papers, 1954-2006 at Emory University contains a significant collection of paper materials related directly to James E. Hinton's filmmaking career.

Collections of Hinton's photographs exist in the Library of Congress, the National Portrait Gallery, Emory University and the High Museum of Art in Atlanta.