Freedom Outside Reason

The Animated Cinema of Jan Lenica

Well into their careers yet still young, Jan Lenica (1928 – 2001) and Walerian Borowczyk (1923 – 2006) started making films in 1957. Barely liberated from the constraints of socialist realism, Polish art passionately embraced modernism. Abstract painting dominated art galleries. Given the mood of the day, Lenica and Borowczyk’s films provided a welcome sight: experimental and modern, they were in tune with the spirit of their time.

Once Upon a Time… and House, which were respectively the first and third film produced by the duo, proved to be characteristically “modern” on many levels, both formally and content-wise. They did away with the fairytale-like formula that dominated animated films in Poland (and around the globe) at the time. Lenica and Borowczyk’s projects were virtually plotless, and as such they were close to abstraction, gravitating toward the new techniques of cutout and collage. Their debut piece, Once Upon a Time… made direct allusions to what was particularly en vogue in the culture of the era, i.e., abstract art and jazz music. That these references were misleading, and that the artists’ actual knack was for vintage photographs and prints, discarded objects, and naïve art (which inspired their second film, Love Requited, based on Jerzy Plaskociński’s paintings), was of little importance, because modernism was in fact associated with freedom of expression, and Lenica and Borowczyk’s films did seem free, be it in form or content.

From the outset, Lenica and Borowczyk made no secret of the fact that their true focus rested with cinematic pioneers Georges Méliès and the early French avant-garde. “It is our goal to return to visual cinema, conceptualized in contemporaneous terms, enriched by sound and color,” said the two repeatedly. “We refuse to confine ourselves to one genre, but prefer instead to draw from anything that stimulates the imagination, stirs emotions, entertains, and pleases the eye.”

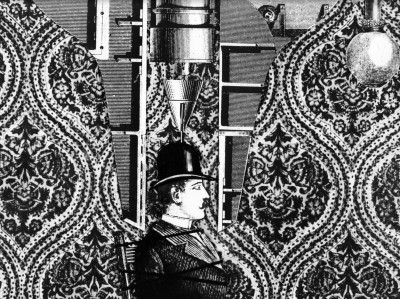

The success of House, which was awarded the Grand Prix at the International Experimental Film Competition in Brussels in 1958, elevated Lenica and Borowczyk to the level of artists whose films were much anticipated by critics. And while they did not fail to live up to those expectations, their internationally acclaimed careers developed along separate lines. Borowczyk followed in the footsteps of early trick film, cinema of metamorphoses, and objects moving without the participation of humans before he reinvented himself as an author of erotic cinema. Lenica remained faithful to his roots in Feuillade’s “Fantomas” films and Chaplin’s burlesque, continuing—with slight exceptions—to work in the grain of what he referred to as a single, lifelong film, albeit cut into smaller chunks.

Lenica’s lifelong film primarily shows that the world is not what it seems to be, making no provisions for romantics and nonconformists. And yet, it also encourages the viewer to continue to bang his head against that brick wall, because a bump on one’s forehead is less compromising than losing one’s face. Last but not least, Lenica reminds his audience that since fads come and go, as do dictatorships and politicians, you should remain true to yourself. The director always stuck to this last principle: he would not yield to novelties and refused to change his style, persistently revisiting the same issues.

In Lenica’s subsequent incarnations of the hero of this neverending story, everyone can find something related to their dreams, fantasies, and experience. In his debut picture, Once Upon a Time…, the main character is but an ink spot that wanders about without a specific purpose and engages in duels with a predatory bird. Lenica’s protagonist returns in Labyrinth, this time as a full-fledged “man in a bowler hat,” equipped with Icarus’ wings and battling ravenous birds in the film’s finale. He appears from the sky as Fantorro the Superman, and dissolves into thin air on the horse Pegasus as New Janko the Musician. In Monsieur Tête and Rhinoceros, he is a clerk who represses his own defiance, only to abandon everything and embark on a long pursuit of the sense of existence in Adam 2. He does his best to help others, but is deceived by appearances: twice, he rescues beautiful women in trouble, unaware that one of them ended up in the clutches of a monster by her own will (Labyrinth), while the other was in fact not a victim but an aggressor (Fantorro, le dernier justicier). It is for these reasons that his nonconformist protest in Monsieur Tête and Rhinoceros is bound to fail. He suffers defeats, because the world he inhabits provides no safe havens for romantics (or any eccentrics in general) of the sort we see in New Janko the Musician. Such individuals are treated with adequate modes of “persuasion,” such as the head-formatting press in Adam 2 or the thought-trapping cage in Labyrinth. Once set in motion, the repressive apparatus acts with mechanical ruthlessness. One anonymous torturer, such as the capital letter A, may be supplanted by another, a no less vicious letter B (A).

Much like a fabulously colorful fish, the visual beauty of Lenica’s gloomy world seems tempting on the outside, luring the unsuspecting victim into a trap. Suggestively erotic flowers (Adam 2) and lusciously curvaceous women (Labyrinth) bait men (males with avian bodies) into a trap; a mysterious cube encourages us to enter it but turns out to be a maze with no exit (Adam 2). Landscape is entirely inhabited by such freakish, camouflaged creatures that beguile us and lie in ambush for one another.

The literary inspirations here are quite evident: Kafka (whose name can be seen on a signboard in Labyrinth), Schulz, Gombrowicz, Themerson, Mrożek, Mandiargues and Ionesco (the latter two contributed narrations to Lenica’s films), Jarry—so we are talking here about the surrealist grotesque and the theater of the absurd. Far more complex is the visual genealogy of Lenica’s imagery, as he drew on numerous seemingly contradictory styles while managing not to abandon his own expression. This is precisely where his greatness manifests itself to the fullest. One could point to at least four sources of inspiration that impacted Lenica’s oeuvre: nineteenth-century graphics, cinematic (pre)history, art nouveau and naïve art.

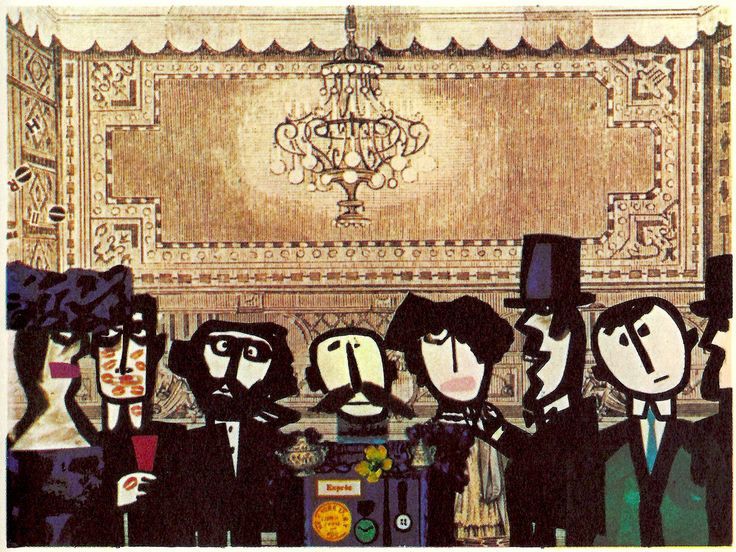

Lenica’s art is consistently of the highest quality. His and Borowczyk’s innovations involved the elevation of the visual as a cornerstone of animated film. Traditionally, the visual had been subordinate to the film’s literary layer and functioned as mere illustration or—as was the case with Eggeling’s and Fischinger’s avant-garde films, or with Norman McLaren’s work—acted as a vehicle for expressing movement, rhythm and visual tensions. Such experiments, as a matter of fact, had been reduced to asterisks in the course of cinematic evolution. On the other hand, Lenica and Borowczyk implanted animated film with the idiom of poster metaphors and graphic shortcuts, which they consistently used in their cartoons. An exemplary case can be found in Monsieur Tête, where the protagonist eventually tames his rebellious tendencies and becomes a model citizen, to the extent that he is awarded with medals, but at the same time his face loses its features, much as in Lenica’s 1958 drawing. “Finally, my head looks just like any other,” he concludes. In Rhinoceros, two bearded intellectuals talk at a café. One of them keeps throwing out names that assume ornate shapes above the table: Dostoyevsky, Sartre, Joyce… his companion responds with short “pffs” that result in the disintegration of the other's elaborate, wordy construction. A is a single, masterfully plain graphic sign: a human being subjected to the terror of the alphabet, a symbol of an individual embroiled in the apparatus of power.

Landscape and Ubu Roi (of which two versions exist, although one may consider them as two separate pieces, given that the latter version—Ubu et la Grande Gidouille—is expanded and includes material from two of Jarry’s subsequent works) come off as Lenica’s most controversial and mature pictures due to their demanding nature. With Landscape, the difficulty stems from its enigmatic, enciphered message, while in the case of Ubu Roi the problem lies in its theatrically static form. Ubu Roi ranks among some of the best, most intense adaptations of Jarry’s text. At the same time, it allowed Lenica to fully unfold his personal catastrophism, one combined with humor and irony, and to question grandiose politics, sweeping utopias and bombastic language.

Landscape metaphorically pictures a piece of Central and Eastern European history. In the film, a certain cruel civilization is superseded by another, scarcely better, that is frantically committed to erecting monuments. Sound familiar? This intriguing film, which Lenica developed during his residency at Harvard, remains one of his most obscure works.

The issue of totalitarianism resurfaced in Lenica’s final film, The Island of R.O., which the artist created following a lengthy hiatus. The project has a long history. Its original idea had given rise to Labyrinth, whose protagonist was a cosmic castaway in a post-Stalinist world. The character returns after forty years, embodied by the well-known animator Piotr Dumała—The Island of R.O. is a live action and trick film.

Unfortunately, The Island of R.O. turned out to be the artistic testament of this distinguished, innovative filmmaker, who died in 2001 before he had a chance to see the final cut of his opus magnum, and the film was completed by his collaborators. – Marcin Gizycki