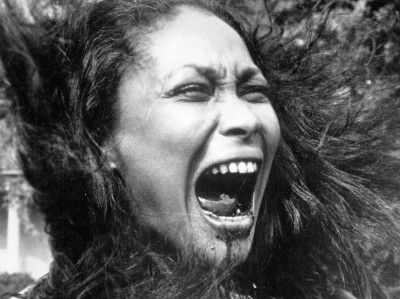

Pam Grier, Superstar!

Rising like an urban goddess from the tumult, confusion and bloodiness of Vietnam, the civil rights movement, the Black Panthers, the sexual revolution, women’s liberation, government conspiracies, assassinations and cover-ups, Pam Grier’s most famous screen personas—Coffy, Foxy and Sheba—seem to have been called into action by a civilization in upheaval. These figures single-handedly detonated layers of oppressive cultural conventions that were desperate for radical revision. Revolutionary even within the low-budget flash of the “blaxploitation” arena that had already blindsided movie theaters across the country, Grier’s films broke away from the action movie pattern that featured passive, two-dimensional female characters on the sidelines. Instead, Grier’s characters were defiant, authoritative, resourceful vigilantes whose intellectual, physical and sexual adeptness American movie screens had never experienced the likes of before. The women she portrayed boldly and bodily, colorfully and brutally, empowered the disempowered. All of the boiling frustrations, all of the silenced voices were violently erupting onto ecstatic movie audiences from a single black woman reclaiming her power on her own terms.

Like her screen persona, the political was always deeply personal for Grier. Part Caucasian, African American, Asian and Native American, she has been aware of discrimination and alienation from all angles ever since her birth in 1949 in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. Her father was a mechanic in the Air Force, entailing frequent moves about the US and back and forth across the Atlantic on and off military bases. She experienced all kinds of communities—those that were harmonious and colorblind or racially segregated and intolerant. A victim of various degrees of racial and gender discrimination throughout her life as well as sexual abuse, Grier notes that she “saw more violence in my neighborhood and in the war and on the newsreels than I did in my movies. Coming from the ‘50s, things were very violent. We were still being lynched. If I drove down through the South with my mother, I might not make it through one state without being bullied or harassed.”

Initially enrolled at Metropolitan State College in Colorado as a pre-med student, Grier felt less inspired by the enormous struggles that path required and was also unable to ignore another calling: her acute desire to be involved in film. Unable to afford film school, the multitalented Grier unintentionally caught the eye of Hollywood when she entered beauty pageants to win prize money for tuition. At first, this attention translated to operating the switchboard at a Hollywood agent’s office as one of multiple jobs she held down while receiving a free introduction to film courtesy of student “guerilla” filmmakers at UCLA. Shortly after switching over to the now legendary, independent B-moviemaking machine American International Pictures as an operator, she landed a small part in Russ Meyer’s Beyond the Valley of the Dolls (1970). Meanwhile, she started appearing in theatrical productions and singing backup for Bobby Womack, Lou Rawls and Sly Stone, among others. By her second film—Roger Corman’s The Big Doll House (1971)—Grier had already secured a leading role. She braved the extremely low budgets and rough conditions of the Philippines production, even handling some of her own stunts and singing the theme song. Her drive and moxie led to role after role in mostly women-in-prison films like The Big Bird Cage (1972) and Black Mama, White Mama (1973), in which she played aggressive survivors who are both tough and voluptuous. Never shy about showing some skin, Grier began her career deeply submerged in the funny paradox of a particular kind of exploitation cinema where women—as characters and as actresses—found both liberation and objectification.

After their major blaxploitation hits like Slaughter (1972) and Blacula (1972), AIP director Jack Hill relocated Grier from fantastic situations in exotic locales to reality-based dramas taking place in America’s own inner cities. Cutting in front of Cleopatra Jones by a few weeks and surpassing it at the box office, Coffy became the first blaxploitation film to feature a black woman as its star and gave birth to America’s first action heroine. In addition to Cleopatra Jones and a handful of others, Pam Grier’s films were the only American movies being made starring a powerful woman of any race in the lead. Able to function adeptly in a man’s world—driving the plot, resorting to violence, making wisecracks—Grier’s complicated characters are also free to make the most of their femininity as a lethal weapon in an arsenal that includes equal parts intelligence and resourcefulness. And still more phenomenal for the time, Grier always portrayed single women with active sex lives who were emotionally and physically protective of their families and the dispossessed. Unlike her tough male cinematic counterparts who toss their ladies aside when business calls, the Pam Grier persona is a fierce fighter, an irresistible aphrodisiac and a tender, loyal lover who is only vindictive when betrayed.

Not a decoration, token or sidekick, Grier’s superheroines shun and disrupt all of the stereotypical African American roles in films—whether male or female—and their inevitable exoticism or submissiveness. If any of her films refer to that history, it is to confront it, upend it and exorcise those demeaning demons. Upon receiving female fan mail, Grier realized that her characters were “doing and saying what [black women] wanted to say.” With a raw energy and the collective anger of generations, Grier forced both blackness and femaleness to center stage. Her characters were not simply on equal footing with their white, male equivalents—they were bent on turning the whole screen inside out.

With Barbra Streisand and Liza Minnelli, Grier quickly became one of only three female stars in the 70s who could open a film. The border now successfully breached, other women soon followed her lead in choosing more potent, commanding female roles over what was often their only other option: the passive, pretty love interest. For a period after Grier’s emergence, there was a greater demand for black actresses in general as well as a trend of female action stars—though mostly on television and primarily featuring white actresses; Get Christie Love! starring Teresa Graves was the single exception.

“My movies were the first they had done with a strong woman character, not to mention black,” stated Grier. “Once they saw the grosses, they wanted to do every one of them like that. I was angry. You can’t give people the same thing all the time… [T]he next time you go for something a little better than you had before.” After fulfilling her contract, Grier left AIP and established her own production company; yet creating and securing complex roles for women proved to be a challenge in an industry still focused on relatively restrictive cages for their female figures. Instead, she studied direction and production, and continued to bring her range and vitality to a variety of roles on television and in films like Greased Lighting with Richard Pryor, Jack Clayton’s Something Wicked This Way Comes (1983) and the Paul Newman feature Fort Apache, the Bronx (1981), in which she chillingly inhabits the part of a psychotic prostitute. However, due to mostly “boring” offers, she turned more to the theater in the 80s, starring in productions like Fool for Love—for which she won a NAACP Image Award—and Frankie and Johnny, in which she played the first black Frankie.

Miraculously surviving a terminal cancer diagnosis in 1988, Grier returned to the screen during a resurgence of renewed appreciation for the blaxploitation hits of the 70s. Films like Escape from L.A. (1996) and Original Gangstas (1996) pay tribute to her trailblazing persona, but it was superfan Quentin Tarantino who most profoundly delivered the great cultural debt owed with Jackie Brown. Grier was able to reannounce herself to the world as not only a treasured icon, but an accomplished actress with a refined style that now seemed effortless.

Grier continues to accept the braver, more meaningful roles. Playing a straight woman in a multiracial lesbian world on the groundbreaking Showtime series The L Word, she once again took on controversial subject matter and helped give voice to another media minority. And in her offscreen life, Grier is actively involved—through various organizations and personally—in coming to the aid of both animals and humans suffering from difficult circumstances. Firmly embedded into the iconography of American culture, Pam Grier continues to make an enduring impact that ultimately transcends both race and gender. – Brittany Gravely

The Harvard Film Archive is honored to welcome Pam Grier to two evenings of screenings and talks, including a conversation with intellectual luminary and Harvard’s Alphonse Fletcher, Jr. University Professor Henry Louis Gates, Jr. The Hutchins Center for African and African American Research, of which Gates is the director, will be presenting Grier with this year’s W.E.B. Du Bois Medal on Thursday, October 6 at 4pm in Sanders Theatre, Memorial Hall, 45 Quincy Street.Tickets are free and available through the Harvard Box Office.