The Waking Dreams of Wojciech Jerzy Has

The career of Wojciech Has cannot be easily categorized. Whereas other post-war filmmakers formed part of the Polish School—dubbed “the cinema of moral anxiety”—Has was a nonconformist with little interest in depicting political tension or romantic heroism. Closer in spirit to western European currents of Existentialism and the avant-garde, he made disparate but formally striking movies. On the one hand, they are quintessentially Polish, beginning with the ravaged post-war landscape of Wroclaw in his first feature The Noose. On the other, his ghosts—literal and figurative—are universal. One can sense in Has’ cinema inspirations as diverse as German Expressionism, American film noir, Surrealism, and the French New Wave.

If Andrzej Wajda has excelled in political, historical or theatrical visions—foregrounding the possibility of individual nobility—Has seems leery of these options. If Krzysztof Kieslowski invoked the possibility of love as a salvation in Three Colors: Blue, White, Red, Has’ characters rarely say, “I love you.” If Krzysztof Zanussi has often dramatized ethical tensions among individuals in contemporary settings, Has was a prose poet of solitude and alienation. A formalist rather than a realist, he crafted stories that explore yearning, weakness and loss. In the documentary Traces (2012), he says on camera, “During Stalinism, we learned that content was important, not form. I think the opposite.”

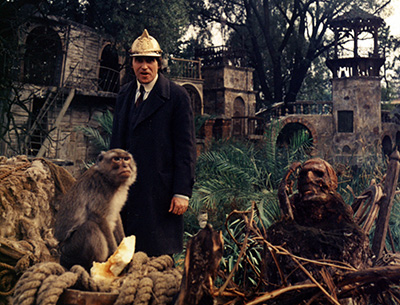

A few of Has’ movies have indeed developed a cult following, notably The Saragossa Manuscript: imagine the hallucinatory displacement of a Polish film—set in Spain—about a Belgian officer, told as a spiraling story-within-a-story. (No wonder it was the favorite movie of The Grateful Dead’s Jerry Garcia.) Rather than writing original screenplays, Has was drawn to novels—the literary limitations that define visual possibilities. One of his most remarkable adaptations is The Hourglass Sanatorium—from stories by Bruno Schulz—including a vividly surreal depiction of Hassidic life in Poland between the World Wars.

Has conveys existential despair through formal elements that make us aware of space (via charged windows) and time (circular narration), particularly in The Noose—a stark poetic drama about a lucid alcoholic who knows he will not succeed in kicking the habit. He loved long takes, deep focus, and unreliable narrators (especially in How To Be Loved).

Pawel Pawlikowski, who directed the Oscar-winning Ida, lauded Has during an onstage conversation that I moderated at Manhattan’s 92nd Street Y on January 4, 2015. When I asked him about the possible inspiration of films like The Noose and How To Be Loved, he said, “Has is a completely unrecognized genius, probably the most talented Polish director since the war, with his own sensibility and vision.”

Nevertheless, he directed only thirteen features, and spent the last ten years of his life as a professor and dean at the famed Lodz Film School. Has was a perfectionist, a nonconformist—often out of fashion as well as political favor—and an inspirational master of cinematic language. His career is ripe for rediscovery. (Copyright Annette Insdorf 2015)