Audio transcription

Haden Guest 0:01

Good evening, ladies and gentlemen. My name is Haden Guest. I'm the director of the Harvard Film Archive. And it's my inordinate pleasure to be here tonight for the opening of our retrospective dedicated to the films of the extraordinary Ed Pincus.

[APPLAUSE]

What more can I say? This is both a celebration of a remarkable artist is also an intervention, because the work of Ed Pincus remains under-appreciated, I think, outside here, Cambridge, where the name Ed Pincus continues to resonate. It is a name spoken with great reverence and extraordinary respect, because of the legacy of his films and of his work here. Ed Pincus began actually as a student of philosophy, doing graduate work here at Harvard, before turning to the cinema. And we begin this retrospective with some of his earliest work. And it's not only Ed Pincus that we're welcoming tonight, but also his co-director on his early work, Mr. David Neuman, and it's a great thrill to have him here tonight.

[APPLAUSE]

And this is a history that the deep roots of nonfiction cinema here in Boston, they are indeed deep and yet have been under explored. We are extremely fortunate, though, to have a book coming out very soon in a year from now by Scott McDonald, one of the great film scholars and historians working in the area of nonfiction cinema and experimental film, and he's going to be joining us tomorrow night and Sunday to participate in this program. And his next book, though, is called The Cambridge Turn in Nonfiction Filmmaking by University of California Press. I'm so excited. And there is, in fact, a chapter dedicated to the work of Ed Pincus.

One reason why I think the films and legacy of Ed Pincus remain underappreciated is the inaccessibility, the unavailability of prints, of copies of these films for theatrical exhibition. That's something that we're determined to change. And some serious work has been done in this regard. We're going to be seeing some new digital video transfers that look really pristine and gorgeous. And I want to thank Ed for all of his tireless efforts to make this program possible. Without him we wouldn't be able to see these films which otherwise exist oftentimes only in unique and very fragile 16 millimeter prints.

So tonight, we're gonna see two films. We're gonna see Black Natchez from 1967. We're gonna see a film called—the first program is two films—and then the second one is Panola from 1970. And I want to welcome both Ed Pincus and David Neuman to say a few words of introduction, then we're gonna have a conversation about the films afterwards. So please now join me in welcoming Ed Pincus and David Neuman.

[APPLAUSE]

Ed Pincus 3:43

Thanks, Haden. When you do a film like this, it's almost invariably at least two main people. David and I worked on the first four or five films that you'll see in this series. Black Natchez was our first film. I was very excited when I saw a sync sound, handheld camera. It just opened a whole new world. These two civil rights workers came up and said, “We could raise money to do a film about freedom schools in Mississippi. Would you be interested?” David was a friend, I asked him if he was interested. We were both interested. And we went into the field, sort of, not being quite sure we're going to do, and that's, I think, an important part of what you're doing when you do a scriptless documentary sync-sound from life.

At the same time that we shot Black Natchez, which was 1965, there was this one character Panola who always related to the camera. And we didn’t know how to cope with that because our ideology was we wanted to film the world independently of the presence of the camera. But we were smart enough, I think, to film him even though he sort of contradicted everything we believed in. To him, life was performance. I'd love it if you looked at both films, and then we could talk about them. David, do you want to say anything?

David Neuman 5:32

No. [LAUGHTER] No, Ed summed it up. We'll talk after the film. So I think the films stand on their own.

[APPLAUSE]

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Haden Guest 5:49

Ed Pincus and David Neuman!

[APPLAUSE]

Well, thank you both for these extraordinary films. And I really want to talk about the dialogue between the two, but I thought that maybe we could start—and we'll start with some questions up here before opening the floor to the audience—speaking a bit about the origin of these two films, what brought you down to Mississippi. Ed, you were studying philosophy at the time, I understand. David, I'd love to know a bit more about how you were brought into this project as well.

David Neuman 6:36

Well, Ed was studying philosophy, but he was also making a movie at the time. Right? A fiction film. But Ed and I had a mutual friend, J.D. Smith, who had gone to Mississippi in ‘64, which was the summer. We were there in '65, and we thought the guys that were there in ‘64 were the real heroes, because I mean, that's when Goodman and Chaney and those guys got it.

But they had been down there and they came back. And they started talking to us, as I recall, in March of ‘65. We didn't go down until July or August—right?—before we got down there. But it was right at the time the Selma march was happening. But the impetus of it was, as Ed had mentioned earlier, was that that they wanted us to come down and to be frank with you, one of the selling points, and one of the reasons we got involved was because we were able to set up a nonprofit corporation. Actually, we didn't set up a nonprofit; we used a church that already had the tax-exemption, and we could raise money through that church. And so it was a way to fund the film. And we went down with almost no money; we funded the film after we got back. And that just the sequence that you saw, just starts with the National Guard jeeps that goes on for a long time, which is in front of the NAACP offices, where the guy [?Ware?] gets up, and you know, all that. We cut that as a single—I don't know, it was twenty-five-minutes or so right?—film to use to raise money. And that was the first sequence we cut. And then we showed that around to raise money after we got back to finally pay for the editing of the film, paying off the lab fees.

Ed Pincus 8:29

So, it wasn't clear where the civil rights movement was in late 1964. Some people said it was over, some people said it was just beginning. And it seemed that this technique was just the right technique to go and make your film where you could deal with ambiguity. And that was really appealing to me.

Haden Guest 9:02

Well, let's talk a bit about direct cinema. I mean, Black Natchez is often held up as a sort of quintessential expression of this mode of cinema, this direct cinema which is very much in the air at the time. And then Panola is a sort of response of sorts to that. I was wondering if you could speak about what sort of expectations, ideas, ideals you had, as filmmakers, in thinking about making it and how—the method, the techniques and technologies that you were bringing to the subject, the way in which you were making this film, and which ways were you thinking of this in terms of direct cinema? In what ways were these ideas and ideals challenged by what you actually found when you began filming?

Ed Pincus 10:00

Well, for example, we were real idealogues about it, not having any experience.

David Neuman

Purists.

Ed Pincus

Hmm?

David Neuman

Purists.

Ed Pincus

Purists. And, we would have been very critical of a film that had voiceover and we used voiceover.

Haden Guest 10:20

I was gonna ask about that. Right.

Ed Pincus 10:24

And we would have thought of that as a failure. Now that I look back at it, I don't see it as a failure, but at that time we did. What other compromises did we have to make?

David Neuman 10:37

Well, it seems to me that the cutting of the film—I think that we cut the film much more dramatically than we envisioned. In other words, we thought that footage would tell the story. There's a lot of cutting in this film. I mean, this was a hard film to cut, and we spent a lot of time cutting it. We had a lot of footage to cut. I haven't seen this film for almost forty years, so I'm almost like you guys, when I see this film. And I was somewhat surprised at the amount of narrative that we created from the footage. And I don't think at the time, we certainly didn't think we were going to do that when we started. And I think that, as Ed was saying earlier, events dictate a great deal of what goes on. I mean, we went down, and for the first two or three weeks, maybe month, that we were down there, we shot stuff that's not in this film. We shot people at the Freedom House, having these meetings where they get all these kids around and talk to them. Don't you remember all that stuff out there with Dennis? And, you know, one boring sort of thing after another. And then when events started to happen, we followed them. And had they not, I don't know what we would have ended up with had, you know, Metcalf not got bombed, etc, etc.

Ed Pincus 12:23

Let me just disagree with you on something. Okay, I think we started out with the idea that we would film a wide variety of things, and then that a narrative would eventually develop.

David Neuman 12:40

I agree to that. I don't think we ever envisioned the narrative that we got.

Ed Pincus 12:45

No, no, right. But I think the part of what we thought was purism actually was beholden to a certain narrative structure, and the belief that if you stuck with it long enough and were serious enough, that eventually a narrative would emerge.

David Neuman

Yeah, I agree with that.

Ed Pincus 13:09

Okay, fine.

David Neuman

No, I agree with that.

[LAUGHTER]

But again, I don't know that now– I mean, that's what we believed, right? You know, I don't know, I guess you can't talk about what didn't happen, or what might not have happened. But, you know, let's say we lucked out, at least, because I remember–

Ed Pincus 13:28

I think it would have been a more ethnographic film had we not–

David Neuman 13:35

Exactly, exactly. It would have been a much less kind of narrative-driven film, story-driven, plot-driven almost, you can say. And this film has a very strong storyline that's based on the, you know, are we going to march or aren't we going to march?, etc. That really was, I think, not in our minds. We were more concerned with a lot of political rhetoric and political ideals that these people that we closely, I think—or I don't know, I shouldn't put words in your mouth—but I think that we certainly saw ourselves as more sympathetic to the Freedom House people than we did to Charles Evers and the NAACP. I mean, it doesn't really come out that way in the film that much, but at the time...

Ed Pincus 14:33

You know, I think it's part of the force of this kind of filming that you can have those sympathies and even have them in the editing. I see them clearly in the editing, but that now, I disagree with us. There's enough–

David Neuman 14:48

Exactly, exactly. I mean, I don't think that the film is biased in the way that we were biased. That's the funny thing. It doesn't seem to me that the film was as biased as we were.

Ed Pincus

I’ll go along with that.

David Neuman

And it wasn't like we were, sort of, aware that, “Oh, we don't want to be biased;” we just, you know, because again, as I remember at least, we were cutting the film for the dramatic impact. I mean, that doesn't sound like, maybe I should say that. But that's the truth.

Haden Guest 15:20

Could you speak a bit about how you worked together?

Ed Pincus

Yeah, we argued all the time!

[LAUGHTER]

David Neuman

We did. We did.

Haden Guest

[LAUGHING] We got a taste of it right now, right?

David Neuman 15:28

Except when we were shooting. And when we were shooting, it was like one person. It really got to the point where he understood what I was thinking, I understood what he was thinking. And by the way, I mean, maybe this is self-serving, but you shot really nice stuff there. I mean, I love– He was pointing the camera in the right place most of the time. So I just wanted to say that because that was something else that I noticed as I watched these films.

Ed Pincus 15:55

I think in the field, it was great. And then the general structure off, we’d argue about everything that happened, which we should emphasize, but then we would argue in a general way to try to show that the other person was just so stupid that they should listen to...

David Neuman 16:13

I agree. But generally, we were of the same mind on most, I mean, our politics and all, you know, we really have no arguments there. But we did have a lot of arguments about just everyday work in the editing room, because I remember more of editing the film than shooting the film, really.

Haden Guest 16:36

Well, let's talk about the editing, though. And I'd love to talk about Panola. I mean, we see the figure of Panola with that—I don't know if it's the king, the tree king or whatever, the back of his shirt—we see him towards the end of Black Natchez. So that footage was shot at the same time, but it only became Panola a number of years later. Was the original idea that that footage would be part of Black Natchez?

Ed Pincus

Yes. In fact, I think we spent an extra four or five months of editing trying to integrate Panola into Black Natchez, and just couldn't. We both liked Panola, but I think especially David was really fond of sort of what he was expressing and all the contradictions in his life. And so we did try to edit it into Black Natchez, but it was just such different stuff. So the first thing, the Vietnam funeral, basically what happens is, Panola says, “I'm going to make you boys a film today.” And then he goes and he gathers these people together. We didn’t even have our cameras, and we got our cameras, and sort of came in while he's doing his performance. And, you know, pretty much, he's always performing, and we didn't know how to deal with that. We didn't know [?how to film it?], which, thank God–

David Neuman 18:07

Well, I remember thinking that Panola was– You know, racism, and the kind of racism that those people were experiencing at that time and for years before that, and to a certain extent today, is a very debilitating, a very destructive thing. And somehow, what's amazing is the other people in this movie or in the other movie that are so strong and so together, but what I wanted to show and I think you did, too, was, you know, the casualties of racism. Panola, to us, was a casualty. This is what happens to the male psyche in that kind of an environment, and many Black people– The scene in the barber shop, where it's sort of subtext, there's one guy goes out the back door. They didn't want us filming Panola. Panola was just something they didn't want us shooting. They didn't like it. And I remember that, we came back here to Boston, and we showed Panola—I don't think it was the final film—but we showed a bunch of Panola film footage to some Black Panthers in South Boston at a community center. And we were, you know, kind of really scared about how they're going to react to it. And many of them were very, very sort of hostile to it. That wasn't a picture of the Black man they wanted out. But there were a couple of people there who were very, you know, they were in tears because it reminded them of their father or whatever. And so, it was very poignant and it had a lot of power in the Black community, but it wasn't something that the Black community wanted, you know, they wanted everybody to be Martin Luther King. And what's really surprising is how many people as you saw on the other stuff, how many people were courageous and how many people were still able to stand up, all the kind of infighting aside. [PAUSE] Am I wrong?

Ed Pincus 20:08

Yeah.

[LAUGHTER]

Haden Guest 20:14

Well, so how did the film that we saw take form though? I mean, how did you decide on this as a short, as a–

David Neuman 20:28

Well first of all, we didn't cut it.

Ed Pincus

Right. So what happened was we couldn't cut it. We tried to cut it and we were unsuccessful. Then Dennis Sweeney said he wanted to have a go at it.

Haden Guest 20:45

This was some years later.

Ed Pincus 20:46

Yeah. And I let him edit it. And then left for the West Coast and Michal Goldman was working with him, and I didn't like the film that came out, so I wasn't going to release it. And then Michal said, “Give me a chance.” So she cut it. And she would show cuts to my class at MIT. And she did what I thought was a great job. And so then we released it.

Haden Guest 21:22

That's what we saw.

Ed Pincus 21:23

That's what you see.

David Neuman

Just one comment. I mean, Michal’s a very good editor and a filmmaker, but so much of that film is not about cutting. It's about, you know, he makes these little presentations, and in the raw footage, it was almost the same thing. I mean, at one point, when we were working on this stuff, I could recite almost every one of those little monologues of his, you know. “I’m Malcolm X Junior, the meanest X devil…” You know, I used to know all that stuff, because it was like vaudeville routines almost. And so, it was very nicely cut, and it finally got put together nicely, but...

Haden Guest 22:01

And his daughter, was that a regular routine too? Where she's asking “How do you make your money?” which I think is one of the great moments.

David Neuman

That's an amazing sequence.

Ed Pincus 22:09

Yeah, yes. That's probably the only somewhat direct cinema sequence in this film.

David Neuman 22:12

Right. And, you know, that was really probably the best scene for us, or at least at the time, that was our favourite, I think.

Ed Pincus

And the tour of the house.

David Neuman

Well, yeah, and the tour of the house. That’s true. Yeah. Which, of course, it was total, you know, I mean, it comes across. I don't think I have to say it, but he's a complete showman. I mean, this was all his idea of a—and I don't think any of the emotion that he supposedly shows in that was real. Do you think so?

Ed Pincus 22:47

I think it was.

David Neuman

You do? I don’t.

Ed Pincus

I think that's, I think, a method actor. That’s real emotion.

David Neuman 22:53

Okay, to the extent that he's a good actor, yeah. But you know, he was always drunk or almost drunk. And, you know, it was acting, I think. And that was the thing that always made me feel very weird, was that we were the white people of the day that he was trying to impress. I mean, he used to go down and wash the police cars. That was one of his jobs. They’d bust him every time they needed to get a car washed. They’d make him wash their car, that kind of thing, you know. And that day, he was– Whenever we were filming him, he was kind of like in Hollywood, you know, the “rainy day set.” You know, when it's raining, you go shoot this. If nothing was happening at the Freedom House, we'd be up there, you know, then we’d go shoot Panola. And a lot of that, because he lived right behind it.

Ed Pincus 23:39

We also wanted to get children and they were the most difficult situations that we encountered, because we were the most exciting thing to come to those back alleys...

Haden Guest 23:52

Right, well there’s that moment where you see that you're chasing the kids at one point, like you’re trying to catch up with them.

Ed Pincus 23:57

That took going pretty much every day. We’d spend fifteen, twenty minutes till we finally could get some sequences, sort of, independent of the presence of the camera.

Haden Guest 24:10

So was Panola always performing like this even when you guys weren't around?

Ed Pincus 24:16

Oh yeah. If he wasn't performing for us, he’d be performing for somebody. He always was performing. He's always on the set.

David Neuman

That's the way he made it. I mean, that was his life's–

Ed Pincus

But he was also a showman. He would go up to you and say, “What does ‘it’ mean? Nobody knows the meaning of it.”

Haden Guest 24:37

Well, that's maybe a good question open to the audience. If there are any questions or comments for Ed Pincus or David Neuman, please raise your hands. Do you have any questions? We have one up here and we have microphones coming to you right now.

Audience 1 24:59

You said a few minutes ago that you disagreed with yourself from that time. Can you talk more about that?

Ed Pincus

Basically, I think that the viability of the Civil Rights Movement did depend on the threat of violence from the Black community. I was ambivalent about non-violence. Now I'm more convinced that it was a theatrical thing to get sympathy. But that really the Watts riots, the possibility of Black men arming themselves, was incredibly important. I think that Charles Evers, who at the time, I thought was a total sellout, was not, and in fact, eventually, not just did mobilize, but was one of the more successful civil rights projects in ‘65. But it's all in the film, you know, so I could see our nasty little cuts.

Haden Guest 26:33

Any other questions, comments? Yes, right here. Brittany will pass you a microphone. Thank you.

Audience 2 26:47

Can you give us a little of the history of what happened, after you left, in Natchez? I mean, how did they get from there to a successful civil rights operation?

Ed Pincus 27:00

In fact, later, the town was mobilized. Evers led huge demonstrations. There were lots of arrests. Then basically, the aldermen backed down and recognized a lot of the demands. A year and a half later, one of the characters in the film was bombed and killed. It was in February of ‘67. We left in September of ‘65.

Haden Guest 27:55

Any other questions? Yes, there's one here, actually Dominique, and then we'll go up front to you, sir.

Audience 3 28:01

Thank you for showing this film. It's really very impressive. But besides the cutting—you were saying a lot about the cutting that it is so action-driven or very dramatic—but the filming itself is also very active, isolating details and moving a lot around. So the editing is somehow echoing what you are doing already while you are filming. So I would like you to say a little bit more how you did already a very participative filming, in fact, instead of observational?

Ed Pincus 28:52

Yeah, you know, I had never shot a film before. I had done still photography. I can see that when I look at the film. It is isolating. It's a little too jumpy for my taste. But on the other hand, I think the editing brings out the sort of tension in the times and so the camera work functions okay. It's not the way I would film now.

David Neuman 29:33

And I don't want anybody to think that my comments about the cutting and all, that we distorted the reality at all. All I'm saying is we punched it. You know, we punched it up, to the extent that we could. And I don't know, but I suppose a purist would just run the raw footage and say, “Well, you make up your own mind.” It wasn't made that way. But like I said, I don't think we distorted what was going on. Once things really started to happen, when they had all this contention, then we followed that theme. And then we got in the cutting room, I mean, you're taking cutaways, and you're taking jumps that don't look like jumps because you're making them look like continuity cuts when they're really, maybe not. And we were pretty much purists about that at the time, too. I mean, we probably would have done a lot more maybe if we hadn't been so concerned about it. I mean, it took us a long time to decide that the only way to make the thing really move better was to have a narration on it. And that was done after we shot everything, we brought Jackson up and he narrated the film for us, talked about what he'd remembered, and we cut that together. But at the time, we never would have thought we wanted to have a narrator. And there's a minimum amount of narration in it..

Ed PIncus 31:02

And I mean, we called it commentary as opposed to narration for good reason, because we didn't think of it as a narrative—like, you know, what's the word?—like an omniscient narrator.

David Neuman 31:15

It was just a way of getting across quickly what we were trying to move to or, you know, just putting it in a nutshell.

Haden Guest 31:28

Just to remind us of the daunting challenge of editing this film, how many hours did you wind up with after this?

Ed Pincus 31:35

We had forty-four hours, which was a lot of time. In the video world, it’s nothing; it takes two days to do that in the video world. We came back from Natchez, and that was before flatbed editing tables. There were upright Moviolas. We didn't know what they were. We called a friend at GBH who came over and showed us how to load it.

David Neuman 32:02

We wondered if when you ran the film through the Moviola, if you're supposed to mark the cuts without stopping it. That's how stupid we were. Remember that?

[LAUGHTER]

Haden Guest

You tried that?

David Neuman

Well, I think we asked somebody about it, but it didn't take us long to–

Ed Pincus

We learned quick.

David Neuman

Right. And that sequence, which I think is one of the best-cut sequences in the film because it goes on so long, the stuff in front of Charlie’s offices there, you know, where they're back and forth, and it goes on, then they finally come out and say “We haven't gotten anything from the alderman” and all. We cut that, as you know, to stand on its own to raise money. That was like, what, twenty-seven-minutes or something. And it stayed in the film pretty much like we cut it. And that was the first thing we cut.

Audience 3 32:54

I have just a follow-up question about the commentary. How did you elaborate the commentary together? Did you write it? Did you work together?

David Neuman 33:14

He came back here and we put a tape recorder in my brother's apartment because he was out of town for a couple of weeks. And that was down here on Harvard Street. And Jackson had never been out of Natchez as far as I know. I mean, it was a big deal to get on an airplane and fly up here. It took over a week, and he was very bad at it first. We didn't write it. We talked to him and then we would listen to how he would say things, but in the end it was almost scripted in the sense that you know, we worked back and forth till we got something we wanted and it was very difficult to do.

Audience 3 33:52

But was it with the images or without the images?

David Neuman 33:56

Without images. It was all done on a reel-to-reel tape recorder.

Haden Guest 34:02

This gentleman here in the front had a question. Brittany will bring the microphone down to you, and we'll just take probably one more because we have to get ready for the next show.

Audience 4 34:14

So wondering [if there] was there any confrontation? I mean, the story's kind of linear. Did you cut out some scenes where like people were saying, “Who the hell are you guys doing down here?” And there's that whole thing with the white organizer? I don't know exactly what her role was. I mean, were there scenes with her?

Ed Pincus

Yes.

Audience 4

I mean, it was very chaotic. I mean, it's a very kind of chaotic period. Obviously someone's been bombed but when you watch the film, it kind of moves along: oh yeah, that makes sense. But you know, it was anything but that I would imagine.

Ed Pincus 34:46

This was a really unique historic moment. where basically in the Black community, we were looked at as neither Black nor white. We were looked at—for the most part, not exclusively—as sort of guardian angels, and so we didn't actually have to say anything about what positions we were taking, but people protected us. And we had a great deal of freedom within the Black community, and no contact at all with the white community. And I think it would have ruined our relationship in the Black community if we did have access to the white.

David Neuman 35:32

It would have been impossible. Ed had gone down to Natchez a year ago or so. Right? And he talked to some white people who came to the screenings. And you can tell the story better than I do, but my point is that when he told me that there were white people in the community who were very sympathetic to what was going on, that Mayor Nosser was actually a good guy, etc, etc, etc., I had these feelings, “God, you know, it would have been a much better film if we had gotten sort of both sides of it.” But the truth is, well, first of all, at the time, I don't think we ever even thought of doing that. I mean, we I don't think we ever for a moment thought, “Well, we're gonna film in the white community.” Did we? I don't recall ever.

Ed Pincus

No, we didn’t at all.

David Neuman

And I don't think we could have because I think we might have gotten lynched if we got over there. And then at the same time, we would have been distrusted perhaps. We might have had another crew over there, some kind of, you know, shooting–

Ed Pincus 36:31

We had made up press cards. Our offices were in Cambridgeport in Cambridge, and it was Cambridgeport Film Corp. And the police called us COFO Films. COFO was the Council of Federated Organizations, which basically was SNCC in Mississippi, Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. So they looked at us as basically civil rights workers.

David Neuman 37:04

The story that people kept telling us was, “The only thing they hate worse than Black activists are white guys coming down from the north to shoot it.” And so you know, and I bought that, I mean, I was scared half the time I was down there. I mean, there were moments where it was terrifying. It was so bad that the idea of going over to Vidalia, which was in Louisiana across the river, was like paradise because we got out of Mississippi, and I mean, it was really no different.

But we were talking about a moment. There's a guy in the film who followed us. The police were following us around and he followed the police to make sure– He said, “Don't worry, I'm not gonna let anything happen to you guys.” And he was arrested. One time we got a bomb threat. The house that we lived in was in the Black part of town. And we got a bomb threat and all these kids—I don’t know, twelve, fourteen, whatever—set up on our roof all night to protect us. And I always think that, you know, those were the real, brave people down there.

Haden Guest 38:18

Can you, just briefly... I'd love to know a little bit more about the reception of the film when it was released, if you could tell us something about that?

Ed Pincus 38:27

Well, we got out of debt by showing it on NET Journal, which was this sort of premier educational channel’s documentary program. And after the film was finished, I just felt like I wanted to film everything. And I was going down to New York City and taking a cab from, I think it was called Idlewild at that time, and the cabbie had been a merchant marine. And I was asking him all about the merchant marine. I was trying to figure out if there was a film there. And then he stops the cab at a light and said, “I saw a film last night on television.” He describes Black Natchez. He said it had politics, it had humor, it was dramatic. He said, “Make a film like that!” [LAUGHTER] So I couldn't wait to tell him I made the film and he couldn't care less! [LAUGHTER]

So, the NAACP threatened suit.

David Neuman 39:41

That's right. They sent a telegram to—I always say PBS, but it wasn’t PBS, whatever it was—threatening a lawsuit that was from Roy Wilkins himself.

Ed Pincus 39:58

Right.

David Neuman

Because I guess they saw a bias against Charlie.

Ed Pincus

I can't remember much when that–

David Neuman

My answer to your question is… other than Robert Coles who wrote a really nice review in the New Republic, I don't recall much response because I don't remember very many people seeing it. It went on television and then I don't know. Ed’s shown it around a lot more. I mean, everybody was, “We really liked your film,” but I don't remember it ever being in any festivals or–

Ed Pincus

It was.

David Neuman

It was. What?

Ed Pincus

New York Film Festival.

David Neuman 40:47

Yeah, but that wasn't awards. They don't give an award.

Ed Pincus

So it was actually interesting, it was so crowded that we couldn't get in to see it. And it was mostly a Black audience. And we were sitting outside, and there was an incredible amount of laughter and the film is a comedy if you, sort of, know enough, and the audience totally expected us to be Black. And we walked out—we had just finished doing the hippie film. So we were both well-dressed, but we had beards—you could cut the hostility in the room. And I'd say, half the people just walked out.

David Neuman 41:35

And I must say, I don't know if I should say it, but it's the same kind of feeling I get now when I see it tonight, you know, it's like, look at those white guys making all these statements in a way about these people down there, because I mean, at the time, to be honest, we had a lot of chutzpah, I guess you'd say, right.? I just feel that we thought that we knew the answer to all this stuff.

Ed Pincus

Well, we did. We were cocky.

David Neuman

“Cocky'' is the word, I think. And there are things where I kind of like, cringe a little bit. It's some of the cuts and all, and again, we chose to look at it that way. Because we weren't sentimentalists, we had no sentimentality about it. And that's more what I'm talking about. I don't think that we distorted anything at all, but we just took the shots where we saw them and looking at it now, as you get older, you try to be a little more conciliatory in a way and we weren't at that time. We weren't at all conciliatory.

Haden Guest 42:48

You were flummoxed by Panola. [LAUGHS]

David Neuman 42:51

Well, you know, Panola was a whole other thing, and again, like I said, I think Panola made his own movie. I mean, you know, we shot it, but it was his movie.

Haden Guest 43:03

He was the director.

Ed Pincus

He was the director.

Haden Guest

Well, we are going to take a break. Everybody who bought a ticket for the show can come and see the next two films, One Step Away and Harry's Trip, and we'll be welcoming back Ed Pincus and David Neuman, but for now, please join me in thanking them both for these remarkable films!

[APPLAUSE]

David Neuman

Thank you. Thank you.

©Harvard Film Archive

The advent of portable sync-sound equipment in the early 60s meant, for the first time in the sound era, that filmmakers could go to the subject as opposed to bringing the subject to the camera. The ability to take a camera out into the world created the desire to "get it right," to film the world independent of the act of filmmaking. In the US, all sorts of rules were being created in documentary film — no script, no narration, no interviews, no lighting, no mic boom, no collusion between subject and filmmaker.

In 1965, the second year of intense voter registration drives in Mississippi, we decided to make a film in the southwest corner of the state. Little civil rights work had been done there because of the danger in the region. Our approach was to seek out several story lines and then continue with the most interesting. A car bombing of a civil rights leader while we were there changed everything. The event emphasized the rifts in the black community around the demands for equality. Rifts between teenagers and women on one hand and the black business community on the other. Rifts between black males forming armed protection groups and the call for non-violence by the major civil rights groups. And rifts between grassroots organizations and more traditional leadership organizations such as the FDP (Freedom Democratic Party) and the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People). – EP

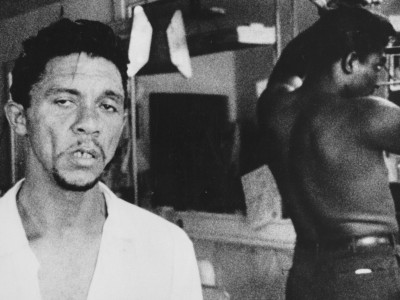

Panola’s life was a performance. He was always “on the set.” Wino, tree pruner, possible police informant, philosopher, "the most dangerous X that ever was," "father of eight with one more on the way," Panola challenged our filmmaking convictions. In no way could we film him independently of the presence of the camera. The conflict between our aesthetic convictions and the reality and authenticity Panola expressed led to few years of confusion, unsuccessful attempts at edits, and ultimately the need to find an outside editor (primarily Michal Goldman). – EP

Tickets include admission to 9:15pm show.

Part of film series

Screenings from this program

Diaries (1971 - 76)

The Way We See It / Portrait of a McCarthy Supporter

Life and Other Anxieties

The Axe in the Attic