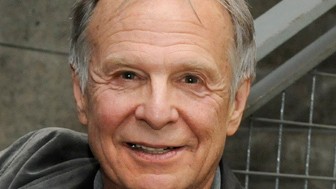

Ed Pincus,

Lost and Found

For half a century, the Boston area—and Cambridge in particular—has been the fountainhead of American documentary filmmaking; Ed Pincus remains one of the crucial figures in this history. Having studied philosophy and photography at Harvard, Pincus turned to film and in 1967 made a significant contribution to “direct cinema” (that is, fly-on-the-wall observational filmmaking) with Black Natchez. Pincus and David Neuman traveled to the Deep South with a camera rented from John Marshall to record the African-American community in Natchez as it struggled to decide how to effectively challenge white racism. In a second feature, One Step Away (1968), Pincus and Neuman (who again took sound) focused on members of a San Francisco hippie community, questioning whether the hippies were fundamentally different from the society they were rebelling against, and confronting the then popular assumption among documentary filmmakers that editing in observational cinema needed to be invisible.

In 1967, Pincus was hired to teach filmmaking at MIT, where he was soon joined by Ricky Leacock. Together they were the heart of the MIT Film Section into the 1980s. The freewheeling Film Section nurtured not only prospective filmmakers among the MIT student body, but non-matriculated men and women who had promising ideas for documentary films. Pincus continued to develop his expertise with the filmmaking process, and in 1969 the New American Library published his Guide to Filmmaking, a widely read and widely used guide for independent filmmakers. Later Pincus would team up with Steve Ascher to expand the Guide, and they transformed it into The Filmmaker’s Handbook—in several editions since 1984.

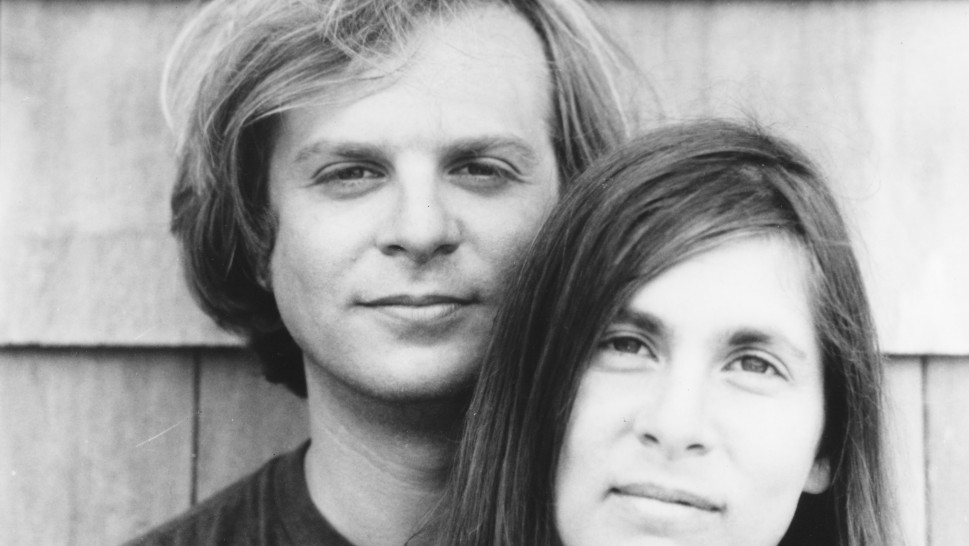

By the early 1970s, Pincus’ approach to filmmaking was changing. The women’s movement and the on-going struggle for black liberation were assuming that “the personal is the political,” and in an attempt to see if this held true for his own experience, Pincus began what would become his magnum opus: Diaries (1971-76). His plan: to cinematically investigate his own (open) marriage and family life during what was an experimental and turbulent time, to shoot footage for five years; then wait another five years before finally editing the footage into a finished film. This plan was adhered to, though Pincus’ willingness to share rushes and early rough cuts of passages of the material became a primary— perhaps the primary—instigation for what is now called the “personal documentary.” Diaries (1971-76) remains one of the masterworks of the genre, and Pincus’ breakthrough has contributed, directly or indirectly, to the films of Ross McElwee, Robb Moss, Miriam Weinstein, Nina Davenport, Jonathan Caouette, Lucia Small and many others.

Diaries revealed not just Pincus’ personal experience, but an increasing self-reflexivity. In 1977 Pincus and Steve Ascher completed Life and Other Anxieties, part personal documentary and part experiment in the mode of cinema verité filmmaking explored by Jean Rouch and Edgar Morin in Chronicle of a Summer – Paris 1960, where the film reveals the filmmakers instigating a situation that is then documented. In Life and Other Anxieties Pincus and Ascher interview people on the street in Minneapolis to find out what part of their lives they would like the filmmakers to document, then document what these individuals have requested. With Diaries, Life and Other Anxieties seems to have completed, at least for a time, Pincus’ investigation of the potentials and limitations of portable sync-sound filming.

Pincus’ “low profile” after the mid-1970s was a result of a bizarre circumstance. Dennis Sweeney, who had helped instigate the visit to Mississippi that produced Black Natchez, had become delusional and dangerous, and was threatening the lives of Pincus and his family. These were not empty threats: Sweeney would kill civil rights lawyer and U.S. Congressman Allard Lowenstein in his Manhattan office in 1980. In order to stay out of harm’s way, Pincus stopped making public appearances with his work and the Pincus family made their rural Vermont farm their permanent residence, working to establish Third Branch Flower, what has become a thriving flower-growing business. Pincus returned to filmmaking in 2005 when the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina and its socio-political implications drew Pincus into collaboration with Lucia Small on what became The Axe in the Attic (2007), a feature about the impacts of the disaster on New Orleans and New Orleanians and on the process of cinematically recording such events.

The strange circumstances surrounding Pincus’ filmmaking career and his early retirement from academe have had the unfortunate result of keeping his considerable accomplishments out of the public eye for nearly a generation. This Harvard Film Archive retrospective offers the first opportunity in decades for the public to experience Pincus’s better known films and, equally exciting, to hear Pincus discuss his work with his most important collaborators. For all practical purposes, this program will provide a public premiere of four lesser known films made in collaboration with David Neuman during 1969-70: Harry’s Trip, Portrait of a McCarthy Supporter, The Way We See It and Panola. – Scott MacDonald, author of The Cambridge Turn in Documentary Filmmaking, forthcoming