The Lost Worlds of Robert Flaherty

“First I was an explorer, then I was an artist.” - Robert Flaherty

His own story draped in myths and mists, pioneering filmmaker Robert J. Flaherty (1884 – 1951) gained his mammoth status in film history from assiduously carving poetry and legends out of real lives. As adventurous, determined and self-reliant as any character in his films, Flaherty trekked to dramatic, remote regions to experience, record and if necessary, recreate the remaining vestiges of the “primitive” lives he deeply revered. Even when working with subject matter closer to home, Flaherty seemed to actively collaborate with “reality” to make the translation to film as awe-inspiring and deeply felt as the wonders of life and ideas were to him. Part poet, part explorer, he never strictly conformed to the ideal of objective documentation or authenticity—a continual source of academic and ethical contention—instead, he exploited the veracity of film and its persuasive powers in order to restore humanity to a more natural state, living in harmony with one another.

As a restless, intelligent boy in Michigan, Flaherty spent little time in school and more time living a nomadic, frontier life with his father, a mining engineer. Prospecting for gold and iron ore from camp to camp in Canada, the young Flaherty learned how to survive in the wilderness from the miners and the local Inuit. In the midst of this exploration, he discovered his future wife and lifelong collaborator Frances J. Hubbard during a brief sojourn at the Michigan College of Mines. Finally after a second treacherous expedition to the Hudson Bay area he bought a Bell and Howell 16mm camera and took a three-week course in photography from the Eastman Company in order to simply make a visual record of the fascinating lives and customs he witnessed in the frozen, desolate Canadian North.

Focused on correcting the troubling gaps he recognized in his initial efforts to record Inuit life, Flaherty stumbled into the depths of a new obsession. As would be the protocol for Moana and Man of Aran, he set to work building an ad-hoc film processing lab in the challenging Arctic conditions and trained his Inuit friends to be his technicians. Immersed in the culture for over two years, Flaherty embraced the new artform as a transformative vehicle to show modern audiences that without all the complications and trappings of modern civilization, lives could be happily lived—even under nature’s harshest conditions.

Working to present a form of life untainted by Western civilization, of course, Flaherty tainted it himself by rearranging it to serve his own romantic ideal which the cultures in question often could not even maintain. “Sometimes you have to lie,” Flaherty explained. “One often has to distort a thing to catch its true spirit.” Shortly after Nanook of the North took the world by storm and later Man of Aran, questions of authenticity arose, but not of sincerity.

As if convinced of the essential goodness in all, Flaherty’s endlessly inquisitive camera eye pursued creatures expressing themselves purely, instinctively through their direct interactions with each other and their environment. Observing patiently and intently through long-focus, detailed tableaux and an intuitive, innovative use of the gyro tripod to follow movement, he embedded scenes with a naturalistic suspense and drama. Known for an extravagant shooting ratio, he conferred an almost mystical power to the very process of filmmaking, asking the film to show him the story. This was not straightforward education or entertainment; it was art. Flaherty preferred shots and stories that did not reveal everything, leaving an audience confronted with his passionate, sublime visions “wanting to know more.”

His adventures on location directly reflected in the drama onscreen, Flaherty overcame enormous physical and technical challenges filming in remote, rugged locations, only to confront more insurmountable ones within the precarious wilds of commercial film distribution and studio production. Flaherty was an esteemed figure in his time, yet continually frustrated by the creative binds of the box office and those who could not comprehend his unusual methods. A colorful, tumultuous career riddled with forsaken films and unrealized projects, Flaherty's trailblazing path echoed that of another passionate, independent spirit, Orson Welles—to whom Flaherty sold a story for Welles' own unfinished film It's All True.

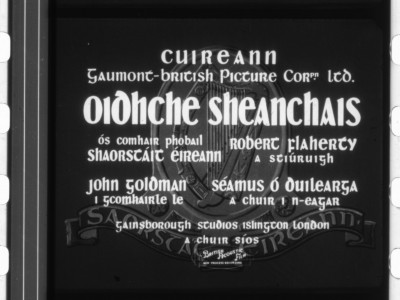

Over the years, Flaherty's films have benefitted from preservation, restoration and most recently, dramatic rediscovery. His daughter Monica Flaherty took the restoration of Moana one step further by meticulously recreating a naturalistic soundtrack for her father's formerly silent work, and was able to finally complete the extended process on DCP last year. In 2012, curators at Harvard's Houghton Library found a long lost nitrate print of Flaherty's short film Oidhche Sheanchais (A Night of Storytelling). Aside from being a precious missing piece of Flaherty’s spare output,it is the first sound film in the Gaelic language, and it features the cast of Man of Aran. This momentous find was restored to 35mm and premiered at Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna last year.

Fully immersing himself in their lives and involving the subjects in the filmmaking process, Flaherty created a unique documentary form which seen from today's vantage—as the concept of “documentary” is continually widened and challenged—approaches a more experimental and innovative hybrid shape. Flaherty's fearless ventures into the unknown were exhilarating turning points which ultimately opened the door to endless possibilities in the worlds of both fictional and ethnographic filmmaking. — Brittany Gravely

The Harvard Film Archive is thrilled to present a retrospective of Flaherty’s work including Moana with Sound, the 2014 2K digital picture and sound restoration of Monica Flaherty’s 1980 16mm sound version of the 1926 35mm silent film by Robert Flaherty and Frances Hubbard Flaherty. The film will be presented by Sami van Ingen, visual artist and great-grandson of Robert and Frances Flaherty, who produced the restoration with film curator and historian Bruce Posner.

We are also presenting the local premiere of Oidhche Sheanchais which will be accompanied by a symposium focused on the film's significance and history Thursday, February 19 from 2pm – 4pm at the Harvard Film Archive, followed by a reception at Houghton Library. The afternoon will include presentations by Catherine McKenna and Natasha Sumner of Harvard’s Department of Celtic Languages and Literatures, among others.