Med Hondo and the Indocile Image

Med Hondo (1935-2019) belongs in the pantheon of the Pan African struggle for emancipation. He will forever reside alongside historians Cheikh Anta Diop and Joseph Ki-Zerbo; political leaders Kwame Nkrumah, Malcolm X, Patrice Lumumba and Thomas Sankara; critical cultural theorists Aimé Césaire and Frantz Fanon; and filmmaker Ousmane Sembène in their collective drive and battle to produce and secure a new image and place for Africa in the world.

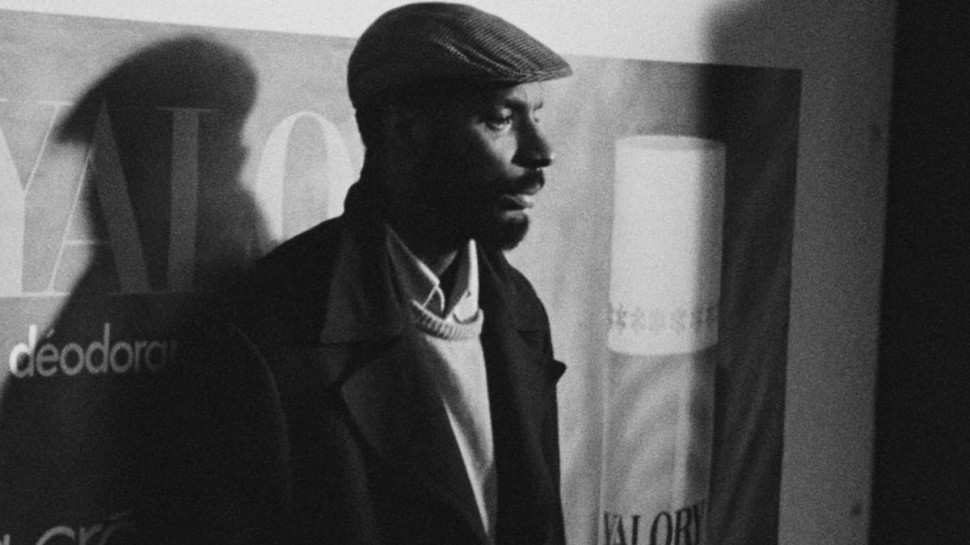

Along with Sembène, Med Hondo was a founding father of African cinema and one of the most talented, versatile and influential filmmakers to emerge from the continent. Hondo was an actor, director, screenwriter, producer and distributor who worked in and mastered a variety of mediums including the theater, radio, television and film. But it was primarily for his two roles as actor and as director that he would be most renowned.

Born in Ain Beni Matar in Morocco in 1935, Med Hondo attended French and Muslim schools before studying to become a hotel chef and migrating to France in the late 1950s. It was through the theater that he began his artistic practice, first in Marseille and then in Paris where he took courses with the late Francoise Rosay, a famous French actress and a close acquaintance of Lee Strasberg and Elia Kazan, who sought to convince her to create an Actors’ Studio in Paris.

The theater presented Med Hondo with both aporia and possibilities, including opening up an illustrious acting career. While he played the European classics (Molière, Shakespeare, Racine, etc.) he soon realized that the theater lacked meaningful roles for Black actors, which led him to join forces with other African and Afro-Caribbean actors in Paris to found their own theater groups—Shango, and then Griots-Shango—and adapt plays by such playwrights as Aimé Césaire, Amiri Baraka, René Depestre, Guy Menga and Daniel Boukman among others.

It was thus the theater that landed him roles in radio, television and cinema. In the latter, he played parts in films by such directors as John Huston, Jean-Luc Godard, Roberto Enrico and Costa-Gavras, among others. To many people around the world, however, in particular in France, and across the Francophone world, it was his voice that nurtured the cinephilic upbringing of generations of spectators, as he dubbed major African American actors in Hollywood including Muhammad Ali, Sidney Poitier, Eddie Murphy, Morgan Freeman, Denzel Washington and many others. Finally, it was also acting that paved the way for, enabled and sustained his independence as a film director, allowing his to craft and nurture a unique and unprecedented cinematic “voice.”

With a directorial career spanning six decades, Med Hondo directed thirteen films, including three shorts, his inaugural Ballade aux sources (1965) and Roi de corde: partout peut-être ou nulle part comme convenu (1969), with which he tried his hands at directing, and Mes voisins (1971), his response to Louis Malle’s Calcutta (1969). It took his feature films to allow him to make an indelible mark on the map of cinema in Africa and across the world. His first masterpiece, Soleil O (1970), was selected at Cannes Critics’ Week and won the Golden Leopard at Locarno the same year. Les Bicots-Nègres, vos voisins (1974), his second feature, secured his place in the pantheon of African cinema with the Golden Tanit at Carthage in 1974. West Indies, the Fugitive Slaves of Liberty (1979) consecrated his absolute mastery of film form. In the seventies—his most prolific decade—he directed three additional documentaries, including two devoted to the liberation struggle of Western Sahara, entitled Nous aurons toute la mort pour dormir (1976-77) and Polisario, a People in Arms (1978), as well as La faim du monde, which he co-directed with Theo Robichet in 1979. Sarraounia (1986), his sumptuous anticolonial epic, which was his only feature in the 1980s, won the Golden Stallion at Africa’s most important film festival, the Pan African Film and Television Festival of Ouagadougou (FESPACO). He directed two features in the 1990s, Lumière Noire (1993) and Watani, A World Without Evil (1998), followed by his testament film, Fatima, the Algerian Woman of Dakar (2004), in which he performs a great work of Pan African(ist) “cine-care” bringing into conversation West and North African cultures. From the year 2004 to his passing, Med Hondo devoted his energies trying to raise funds, cast and direct what he saw as the crowning film of his career, Toussaint Louverture, The First Among the Blacks. However, the political economy of both African and world cinemas contributed to making the film impossible.

On March 2, 2019, on the closing day of the 50th anniversary of FESPACO, a festival he helped build, Med Hondo passed away in a hospital in Paris bequeathing an immeasurable cinematic and artistic legacy to generations of spectators to come.

Med Hondo’s Politico-Artistic Avant-Gardist Project

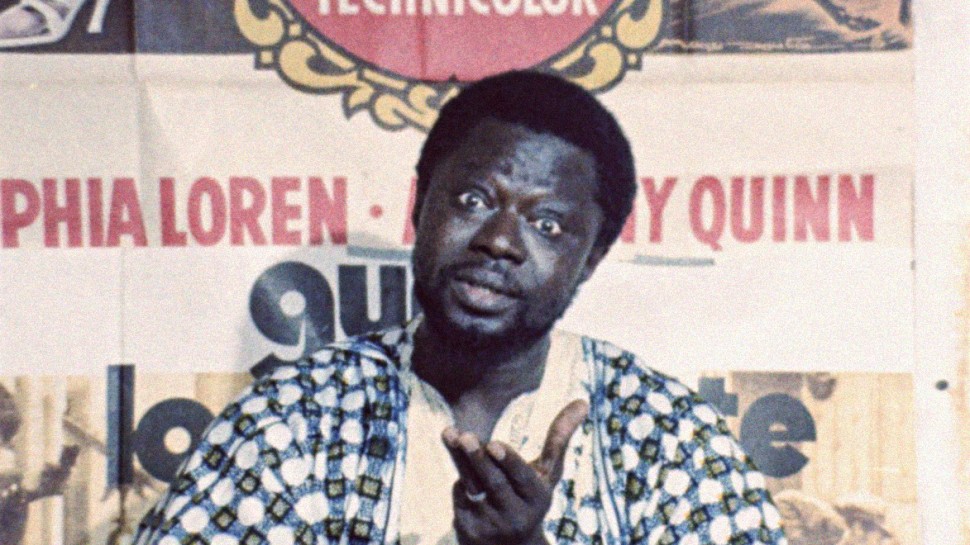

Med Hondo belonged in the continuum of first and second generation African intellectuals, politicians and artists and cultural workers for whom decolonization and independence meant more than the trading of places between the former colonizers and the formerly colonized, but rather a radical avant-gardist geopolitical project that would completely overturn the colonial order of things and usher in a new world whose structural and structuring foundations would be radical equality, justice, dignity and liberty for all. For Med Hondo, the cinema had its part to play in the realization of this avant-gardist vision. Similarly, he saw this avant-gardist vision of emancipation as a possibility to emancipate the cinema itself from all forms of dominance including that of certain forms and traditions. Indeed, he famously said once:

I cannot bear to see human beings deprived of their dignity. This is the meaning of my struggle… I have always strived for a cinema of rupture, because I consider that Africans, African civilizations, Black people have their own history, their own destiny, their own expression, and that the cinema they make cannot be the classic cinema made by everybody else, with a beginning, a middle, and an end, kisses, feelings, love, etc. I did not want to swim in that pond. I always told my colleagues to make sure not to imitate the Other cinema. They could of course be inspired by it, by many of its qualities, but not mimic it. For me, the dogma, if any, was to never imitate...

Throughout his career, his films and beyond, Med Hondo sought to actualize this vision in his choice of emancipatory themes, a radically and formally innovative approach, an uncompromising and critical bidirectional gaze, and in his contributions to the creation and/or nurturing of important African cinematic institutions such as the Pan African Film Festival of Ouagadougou (FESPACO), the Pan African Federation of Filmmakers (FEPACI) and the Comité Africain des Cinéastes (CAC).

Thematically for instance, he was one of the first to center the problematic of migration in his cinema by devoting no less than seven films to it and exposing its historically overdetermined nature. He was also one of the first to revisit the African anticolonial struggle and foreground Queen Sarraounia, a female figure, as his protagonist. The radical potential of the film was demonstrated when the French government reportedly put pressure on the Nigerian state to cancel the shooting agreement made with Hondo, forcing him to make the film in the more revolutionary welcoming environment of Thomas Sankara’s Burkina Faso. Neocolonialism, neo-slavery, Pan Africanism and Black internationalism are centrally featured through Hondo’s work, and prominently so in Soleil O, Mes voisins, Les Bicots-Nègres, West Indies, Sarraounia and Fatima, the Algerian Woman of Dakar. Similarly, the director put many of his films under the gentle protective gaze of important radical figures in the African, Afrodiasporic and world revolutionary movement, from Lumumba and Malcolm X to Che Guevara and Ben Barka (Soleil O), Karl Marx (Les Bicots-Nègres, vos voisins) and, analytically speaking, Marxist theory throughout most of his films), Frantz Fanon and Cheikh Anta Diop (Fatima, the Algerian Woman of Dakar), etc.

Yet Med Hondo’s thematic radicalism is far from self-indulgent. It is structured by a loving yet severely critical bidirectional gaze whereby Western racial capitalism, colonialism and neocolonialism are as equally flagellated as complicit African and Afrodiasporic elites, who are seen as coconspirators in confiscating the emancipatory potential of their peoples. In that sense, Hondo very much embodies the figure of the cineaste as intellectual, so defined by Michel Foucault in the following terms: “What is an intellectual but the one who works so that others do not have such a clear conscience?”

The avant-garde status of Med Hondo’s films is best understood through the concept of the indocile image. Med Hondo’s indocile image is premised on an interrogation of various forms of dominance including the political, the economic and the cultural, all of which have a purchase on the cinematic. It is an image that rests on the historical, holds emancipation as its horizon, questions and interrogates cinematic forms, practices and modes as partaking in ways and means of engaging with the political and foregrounds a specific experience as a model human experience, that of African and Afrodiasporic subjectivity. The indocile image is arguably a non-indulgent image in that it is both premised on and gives prominence to the concept of critique—of self and alterity, of self as other, and indeed other as self. It posits the repudiation of the desire to separate art from life, to confine it to the generation and multiplication of pleasures in the world. Instead, it asks that we expect and demand more from cinema--that it intervenes and participates in transforming the world.

To actualize this vision, Med Hondo deploys a plethora of avant-gardist aesthetic strategies including figuration, direct address, demythification, distanciation, spectator-activation (the production of the citizen-spectator), the articulation of the triad of historical processes, historical consciousness and historical transformation, the adoption of rejected forms (the pedagogic, the didactic) and the creation of new ones (the provisional image), thematization over narrativization, interruption over transparently flowing continuity, the essayistic, the foregrounding of orature, minimalism, non-diegetic characters, etc. Moreover, Med Hondo’s avant-garde cinema is formally agnostic in that it considers every available formal device, genre, mode, filmic and nonfilmic, fictional and nonfictional material open to use as long as they serve the film’s project. In other words, his is an irreverential deployment of film form.

A Cinephile’s Cinema?

At once sober and exuberant, mixing pure and spectacular virtuosity with surprising and sometimes minimalist restraint, Hondo’s is a cinephile’s cinema, not of the navel-gazing and thumb-sucking kind that rushes to the first row of the theater to absorb the first rays of reflected projector light in their spectatorial bodies, but rather a cinephilia premised on the inseparability of the aesthetic and the political. Humorous, caustic, thought-provoking, historically conscious, uncompromising yet profoundly empathetic and restlessly innovative in their mise en scène, montage, sound design and narrativization, the indocile films of Med Hondo invite us to take our destinies in our own hands and forge a world in our own image. – Aboubakar Sanogo, Carleton University

In collaboration with Ciné-Archives in Paris, the Harvard Film Archive—which holds many prints of Hondo’s films—oversaw the digital restoration of West Indies and Sarraounia. These screenings will be their US premieres, and on this important occasion we welcome Hondo scholar Aboubakar Sanogo and Ciné-Archives archivist Annabelle Aventurin to add their invaluable insights into these essential, powerful films and their fascinating filmmaker.