The Complete Federico Fellini

“The golden era is over. I remember the first time I stepped on a rostrum. The thing that hit me most was the complete silence. At the start signal I realize that my baton is connected with the orchestra. Its voice originates from my hand. The baton draws the orchestra out of silence and then back to it. The sound rises like a sea wave when I lift my arm and move it in the air like a wing. And when I lower it the sound fades.”

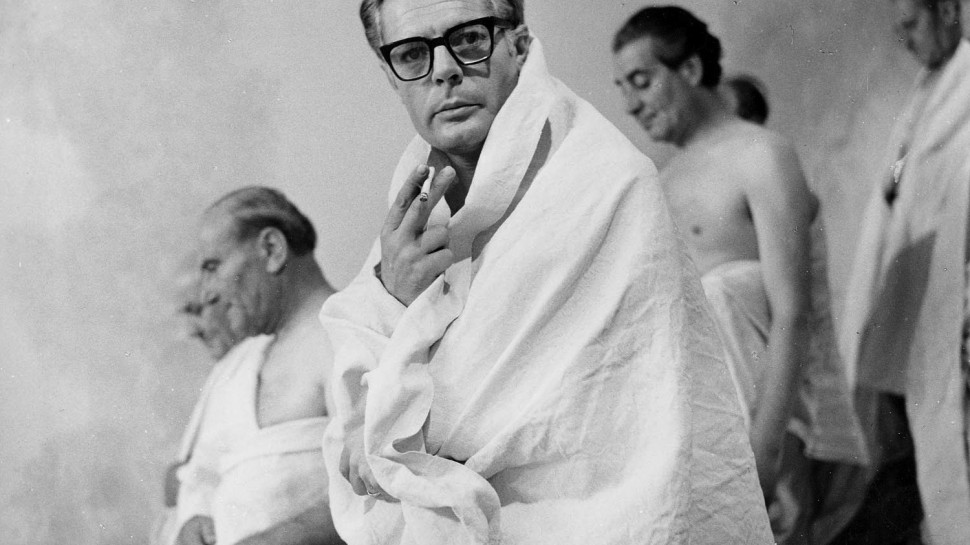

Film directors, when they’re good enough to inspire hyperbole, have often been compared to conductors. They create “visual music” by orchestrating actors in precise movements around sets, summoning crescendos and decrescendos in both rhythm and emotion, using the camera like a baton to punctuate or downplay certain effects. It’s a clichéd analogy—and yet there are few filmmakers to whom it better applies than the Italian maverick Federico Fellini, who would often film to his composer Nino Rota’s music and who went so far as to draw a sustained consonance between himself and the conductor (Balduin Bass) at the center of his 1978 television film, Orchestra Rehearsal. Bass’s character is a contentious figure in the story, a cantankerous skeptic of the strike being staged by his musicians, but he’s nonetheless afforded ample space to pontificate on his craft in a candid, awe-inspired monologue that suggests something Fellini might say about the art of directing—an impassioned argument for the fantasy of complete artistic control.

Through his four-decade directorial career, Fellini came about as close as anyone to achieving that fantasy. The boy from a small seacoast town in the north of Italy—who christened the posts of his childhood bed with the names of the four antique movie houses in Rimini—would eventually go on to command the Italian film industry, though even as his budgets swelled and audiences grew, he never really left his own head. At the height of his mature period, Fellini made elaborate, evocative, expensive films on the backlots of Cinecittà that, although colored by Italian culture, history and politics, were unwaveringly about the deep recesses of his own mind. And though he cultivated a roster of collaborators as formidable as that of any modern auteur, Fellini brought his imagination to the screen with such remarkable tonal consistency, such an instantly recognizable personality, that it can be easy to fall prey to the submissive state described by Bass’s character with regard to his former conductor: “Every concert is like a mass…there was nothing more beautiful than his authority.”

Long before he reached this status, however, the young Fellini auditioned many identities through the 30s and 40s: a grade school delinquent and college dropout, a street-dwelling caricaturist, a columnist for the satirical weeklies 420 and Marc’Aurelio, a writer of radio sketches, and a gag maker for Aldo Fabrizi—then an illustrious entertainer in the world of the Avanspettacolo, or Italian variety show. It was in these early professional dalliances that Fellini became acquainted with some of the figures who would jumpstart the neorealist movement: screenwriters Cesare Zavattini, Sergio Amidei and Bernardino Zapponi, as well as directors Ettore Scola, Alberto Lattuada and Roberto Rossellini. Fellini’s first forays into the cinema came as a screenwriting collaborator with these artists, a role he used to channel the world around him, whether through firsthand experience (helping to dramatize the quotidian heroics of resistance fighters in Rossellini’s Rome, Open City (1945)) or investigative research (posing as a homeless man on the black market to capture on-the-ground insight for Lattuada’s WWII drama Without Pity (1948)).

The first phase of Fellini’s career as a director—spanning 1950’s Variety Lights to 1957’s Nights of Cabiria—grew directly out of these years of creative itinerancy and neorealist germination. It was during this time that the director quickly identified his key colleagues: composer Nino Rota, whose jaunty, waltz-heavy scores for Fellini are the hallmark of his career; writers Tullio Pinelli and Ennio Flaiano, always keen to honor the director’s flights of free association and dream logic; and muse Giulietta Masina, who had also been Fellini’s wife since 1943. The films of this period focus on wanderers and dreamers navigating the harsh realities of poverty and diminished postwar opportunity, yet they are animated by Fellini’s faith in the spontaneous and the magical—a belief nowhere more evident than in Nights of Cabiria, when, after subjecting Masina’s heroine to a string of abuses as a victim of Roman street life, Fellini sends her off in a parade of gallivanting eccentrics that renews her conviction of a better tomorrow.

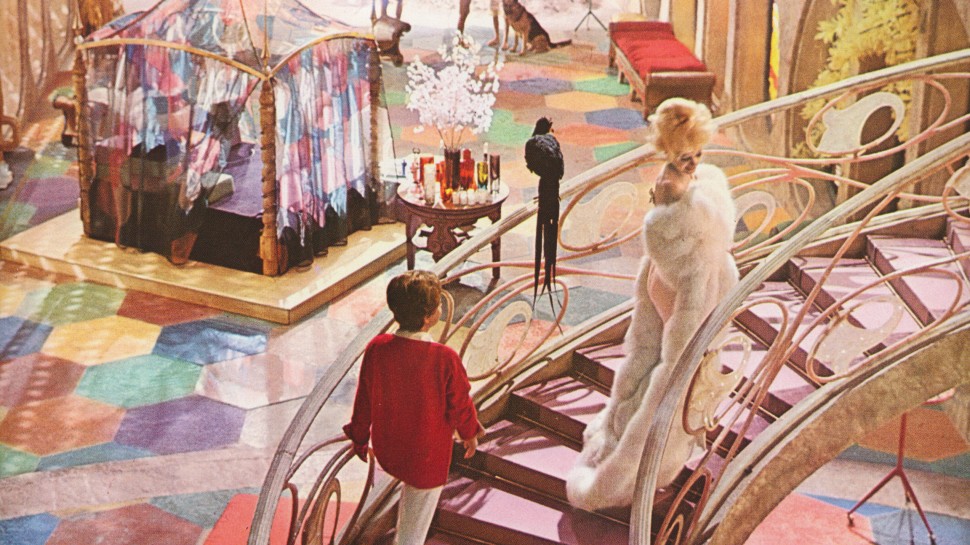

No such motivational whimsy marks La Dolce Vita (1960), the landmark film that would prompt a sea change in Fellini’s filmmaking. If the prior decade of films was defined by conflicts between battered-but-not-defeated souls and their daunting realities, Fellini’s next epoch staged battles within his characters’ own active imaginations—vivid wars between reality and projection, ego and id, that would typically yield no clear resolution. Coming to terms with a rapidly modernizing Italy now scrutinized by the larger world (in no small part due to the success of films like La strada (1954) and Nights of Cabiria), Fellini spent the better part of the 60s bringing to life La Dolce Vita, 8 ½ (1963), Juliet of the Spirits (1965) and the omnibus featurette Toby Dammit (1968)—all audacious experiments in narrative form and visual style that fully announced the arrival of an uncompromising visionary. The most famous of the bunch—the Marcello Mastroianni-starring 8 ½—set a template for the kind of film that would come to be seen as emblematic of the “Felliniesque”: a phantasmagoria of dreamlike set pieces, captured with an ever-mobile camera, dramatizing the inner life of a guileless hero who often stands in for some gradation of Fellini himself.

In a manner that would seem unthinkable in the current big-budget and spectacle-film landscape, the flourishing of Fellini’s prestige and resources throughout the 60s and 70s correlated spectacularly with the director’s increasing use of the medium not as a storytelling engine, but as a playground to give exaggerated form to his deepest memories, fantasies and anxieties. Part of this industry success had to do with the fact that he was a larger-than-life personality, as enterprising as he was jovial. Another explanation was practical: Fellini’s idiosyncratic films brought home the soppressata, so to speak. Many did big business at the domestic box office (more than a handful were among the highest grossers of their respective years), and four of them—La strada, Nights of Cabiria, 8 ½ and Amarcord (1973)—garnered Best Foreign Language Film distinctions at the Academy Awards, with an honorary Oscar later in life bringing Fellini to an international category-leading total of five statuettes (“one for each decade of our love story,” remarked Masina).

Unlike the contemporaries (Alain Resnais and Michelangelo Antonioni) with whom Fellini would be bunched in Pauline Kael’s infamous “sick-soul-of-Europe” designation, the Italian maestro infused his films with a showman’s brio and an eagerness to enchant that he inherited from his childhood fascination: the circus. Though he was often exhuming private obsessions, he worked from a well of cultural memory and indulged a rustic, Rabelaisian sense of humor that spoke to a far broader audience than the intelligentsia. Recurring leitmotifs include large gatherings over food, buxom women who magnetize the eyes of entire male populations, impromptu carousing in abandoned piazzas in the wee hours of the night, travelling amusements scraped together from limited means, and the ambivalent, occasionally blasphemous observation of Catholic rituals—all of which speak to the director’s fondness for the quirks and customs of his homeland, ever-resilient even when challenged by the shadow of fascism (Amarcord), the creep of globalization (La Dolce Vita), or the rise of television (Ginger & Fred).

Already long fascinated by the inner workings of fame and the dream factory—few images recur more often in the Fellini canon than a skyward-facing shot of a cameraman elevated on a crane—the filmmaker in the second half of his career turned increasingly self-reflexive. Fellini: A Director’s Notebook (1969)—an NBC commission that’s half lyrical diary film and half auteur PR—was the first of his projects to embrace a documentary-within-a-film conceit, and The Clowns (1970), Roma (1972), Orchestra Rehearsal and Intervista (1987) followed suit, a few even bringing Fellini himself into the onscreen ensemble alongside a crew of journalists tailing him. Symptomatic of a ballooning ego, possibly, but these impositions of his own presence into his films are also a natural outgrowth for an artist who was among Cinecittà’s resident celebrities for his entire career, a level of fame unhindered even as Fellini’s squabbles with producers over delayed productions and massive financial overages ultimately found him toiling more and more in the less regal domain of television.

Fellini’s increasing examination throughout the 70s and 80s of both his own place in a larger media landscape and the nature of filmmaking within that growing arena coincided with an era now often perceived by unsympathetic critics as a plunge into stale self-parody. A wickedly caustic Dave Kehr pan of the baroque Petronius adaptation, 1969’s Fellini Satyricon (“A shallow, hypocritical film, without a glimmer of genuine creativity”), crystallizes the backlash of a generation of critics skeptical of Fellini’s outsize reputation and industry-wide hosannas. Films like City of Women (1980) and And the Ship Sails On (1983) have often been, at best, reflexively dismissed as nostalgic retreads of Fellini’s greatest hits and, at worst, taken to task as evidence of an out-of-touch artist spinning his wheels. And while it is true that many of Fellini’s tics remained unchanged across four decades—the aforementioned leitmotifs, the use of dubbed sound as an expressive rather than merely practical device, the reliance on a certain canned wind sound effect over and over for dreamy atmosphere—his repeated embrace of new mediums and storytelling forms suggests an artist driven by the challenge of molding his fixations into new shapes and sizes.

On the advice of Jungian psychologist Ernst Bernhard, Fellini kept a dream journal—in his words “scribbles, rushed and ungrammatical notes”—from the late 60s through the 90s (published as The Book of Dreams in 2008), and many of the films in the latter half of his career feel accordingly diaristic and provisional, like sketches on themes. The lack of compromise—or, in some cases, discipline—that enables some Fellini films to spin out in half-digested ideas and images is also the source of their incantatory power. His films can be some of the loudest and most frenetic in the world cinema pantheon, like moving embodiments of the cartoons he so passionately drew in his youth, and yet the mad flurries of activity would often be followed by passages of hypnotic repose, such as in Roma, when a boisterous outdoor feast segues into shots of the dining area emptied out in the middle of the night. According to Pier Paolo Pasolini, Fellini possessed “such an intensity of affection for the world” that “even the air is photographed”—high praise that speaks to both the director’s fluid use of a moving camera and his three-dimensional sense of space, which always leaves open the possibility of something leaping unexpectedly into the foreground.

In the spirit of returning to an earlier refrain, it’s worth noting that Pasolini’s poetic compliment also calls to mind the craft of conducting, which involves gesticulating in the air to, in turn, fill that space with music. In Orchestra Rehearsal, an otherwise unsung deep cut from Fellini’s late period, the striking musicians break out into a chant when Baas’s conductor disappears into his green room: "Orchestra don’t fear, the conductor’s death is near!” In one sense, Orchestra Rehearsal reflects on Italian politics a decade after Sessantotto and the Hot Autumn, but in another it offers an analogy for the fading of its auteur’s fame and industry centrality as cultural appetites were shifting and new voices were emerging. The film absorbs and reflects these seismic shifts with honesty and clarity but also a touch of wistfulness, as hinted at by Baas’s monologue: “An orchestra conductor is like a priest. He needs to have a church and parishioners. When the church collapses and the parishioners become atheists….” He trails off, and, in the silence, we can hear the apprehension of an old titan toward the uncertainty surrounding the future of his art—an apprehension Fellini likely shared. That he never slowed his tempo in spite of it speaks to a simple value instilled in the artist from childhood and only deepened by the onset of the war: the show must go on. – Carson Lund