Godard, Gorin, Garrel and the Grin Without a Cat

“May ’68” has become shorthand for referring to the extraordinary concatenation of student rebellion and workers’ strikes that shook France during that spring month forty years ago, ultimately bringing down de Gaulle but falling well short of the more revolutionary and utopian hopes expressed during the strikes. 1968 was also, of course, a year of unrest worldwide, with antiwar fervor, student movements and backlashes against these uprisings all happening at once. French cinema was a significant part of the movement for change. Indeed many have suggested that the Paris unrest was sparked by protests over Henri Langlois’ abrupt removal from the Cinémathèque française by de Gaulle’s government. To signal their protest, on May 19, at the height of the strikes, Godard and Truffaut led the group of filmmakers that shut down the 1968 Cannes Film Festival.

The meaning of the events of May ’68, their origins and their consequences, have long been subjects for discussion in France, and hence for French cinema. Mirroring in some ways the uprising’s diverse roots in syndicalism, student politics, the New Left, anarchism, Situationism, anti-colonialism and Maoism, the events’ influence on French film has ranged from free-form experimentation to structuralist filmmaking to Marxist agit-prop to workers’ documentaries and newsreels to nostalgia.

For Jean-Luc Godard (b. 1930), the 1960s was a long decade of investigation into modes of cinema ranging from the B-movie madness of Breathless to the big-budget Contempt to the avant-garde aesthetics and guerilla filmmaking of La Chinoise and Weekend. After the events of 1968, Godard rejected narrative illusion for several years, to concentrate instead on a string of films that combine documentary, formal innovation and radical politics. Jean-Pierre Gorin (b. 1943), twelve years younger than Godard, already had a career as a journalist and critic when the two began collaborating. Together the pair formed the nucleus of a collective they dubbed “Groupe Dziga-Vertov,” after the Russian avant-garde filmmaker who sought to document all aspects of life in the young Soviet Union in a celebration of modernism, futurism and Bolshevism. The films of the Dziga-Vertov Group include a wide-range of experimentation that includes radical anti-narratives and documentaries of pop culture and the Palestinian struggle, and culminates in the Brechtian Tout va bien, starring none other than Jane Fonda. The failure of both critics and defenders of the Dziga-Vertov Group films to see the work as aesthetic—as well as political—interventions has been a source of deep frustration for the radical films’ makers.

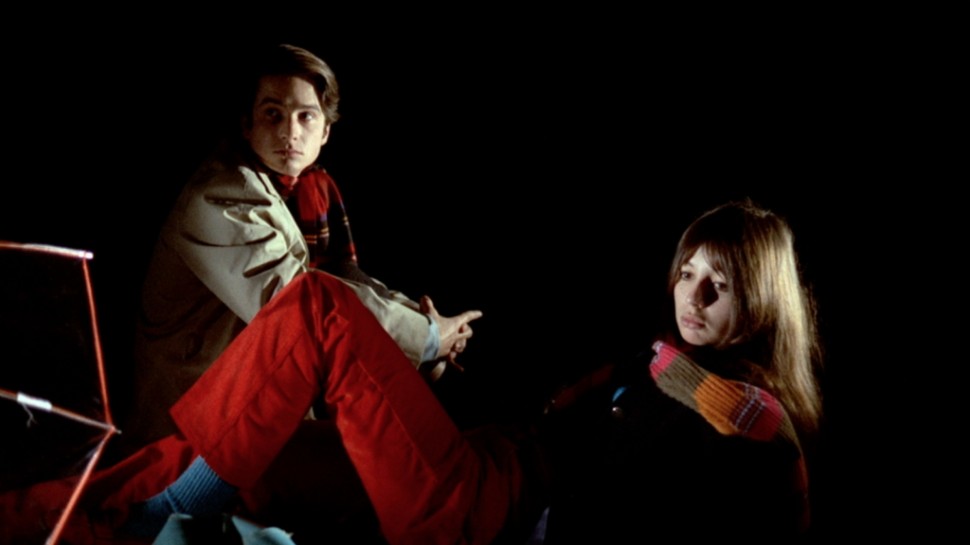

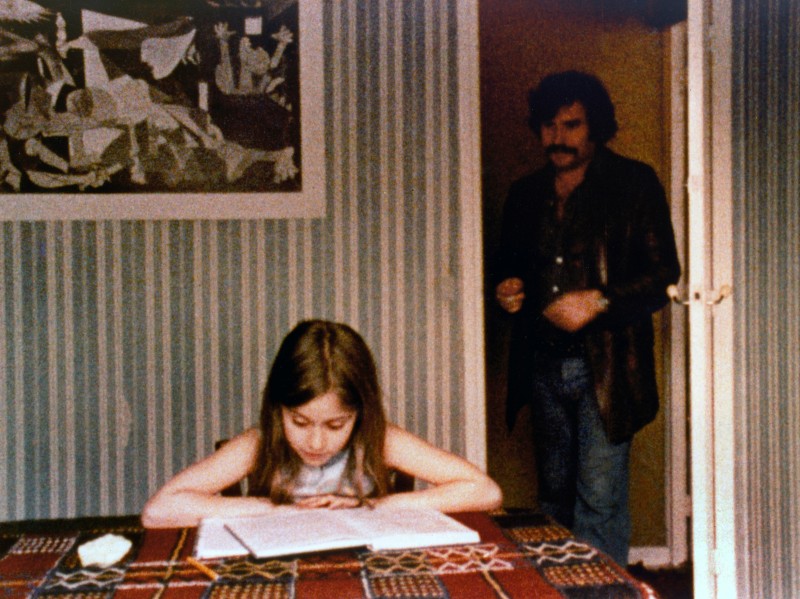

This series extends its focus beyond Godard and the Dziga Vertov Group to include two additional French filmmakers on whom the tumultuous times also had a profound impact. Chris Marker (b. 1921), the iconic artist often regarded as the father of the cinematic essay form, looks back at both the revolutionary politics of the 1960s and the long period of reaction that followed in his far-reaching documentary A Grin Without a Cat. The youngest director whose work is included in this program, Philippe Garrel (b. 1948) experienced May ’68 not just as a historic moment but as a defining experience, as his films illustrate. Le Lit de la vierge, made in the wake of the strike, replays the events as a religious ritual, while J’entends plus la guitare depicts the disillusionment that struck years later. Finally, with Regular Lovers, Garrel recreates the conflicts and disturbances of forty years ago, giving them an almost epic sweep. Together, these three films make a kind of May ’68 trilogy, drawing an arc from revolutionary and aesthetic fervor to despair to remembrance.